The recent BBC drama ‘Vigil’ was set on a fictional Royal Navy Vanguard-class submarine, operating as part of Britain’s ‘continuous at sea deterrent’. It starred Suranne Jones as a detective helicoptered out to join the crew of the submarine to investigate the death of a crew member. Filmed on a specially constructed set, viewers got a real sense of the claustrophobic living conditions, even though the real submarines have even tighter spaces.

Working on a submarine has always meant living 24 hours a day for months at a time in cramped conditions with minimal privacy – hardly an appealing prospect to most people, so you might wonder what would attract someone to join this service?

A current Royal Navy recruitment campaign called ‘Made in the Royal Navy’ consists of short, one-minute commercials showing young people travelling, learning skills and developing into professionals. Each one features a tag line such as ‘I was born in Blyth, but I was made in the Royal Navy’.

Travel and responsibility appear to have been key selling points in Royal Navy recruitment at least since the mid-20th century. A wonderful example of this is the film ‘Voyage North’, which was commissioned by the Central Office of Information (COI) in 1964 and was set on the serving Royal Navy submarine, HMS Artemis. You can watch ‘Voyage North’ on the Imperial War Museums’ film website free of charge.

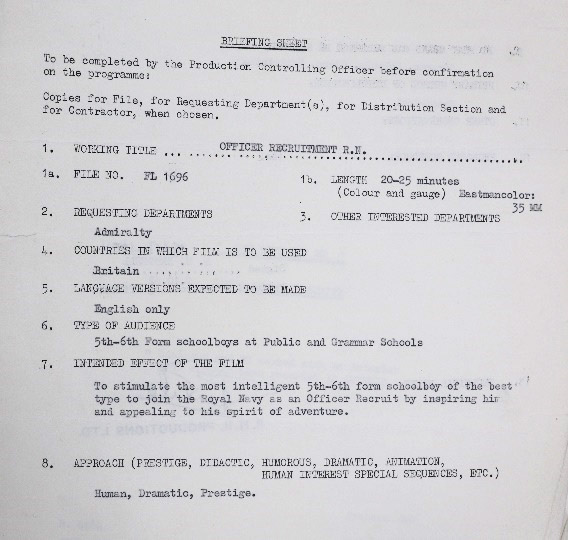

The National Archives has the ‘production file’ for ‘Voyage North’[ref]Production file for ‘Voyage North’: catalogue reference INF 6/2100.[/ref] which contains COI working papers such as scripts, story outlines (treatments) and lists of camera shots required. One document explains that the film was aimed at ‘5th-6th form schoolboys at Public and Grammar Schools’ with the intention to ‘stimulate the most intelligent 5th-6th form schoolboy of the best type to join the Royal Navy as an officer recruit by inspiring him and appealing to his spirit of adventure’.

The film is a little over 20 minutes long and it shows a new young officer, Ellison, narrating his experiences on Artemis as it sails from the UK to the Arctic and eventually to Copenhagen. Early on in the film, Ellison is seen at the submarine base in Gosport with a group of other young recruits. They go through a simulated underwater escape; ascending through 30m of water in the Submarine Escape Training Tank – now known as Fort Blockhouse – which still stands in Gosport.

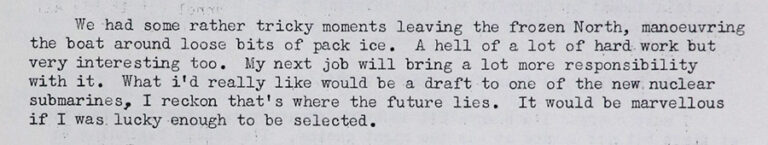

Later in the film we see Artemis edging its way through ice flows and the crew playing cricket on the ice. At one point Ellison narrates a letter he’s writing home, saying:

‘We had some tricky moments leaving the frozen North, manoeuvring the boat around loose bits of pack ice. A hell of a lot of hard work but very interesting too. My next job will bring a lot more responsibility with it. What I’d really like would be a draft to one of the new nuclear submarines, I reckon that’s where the future lies.’

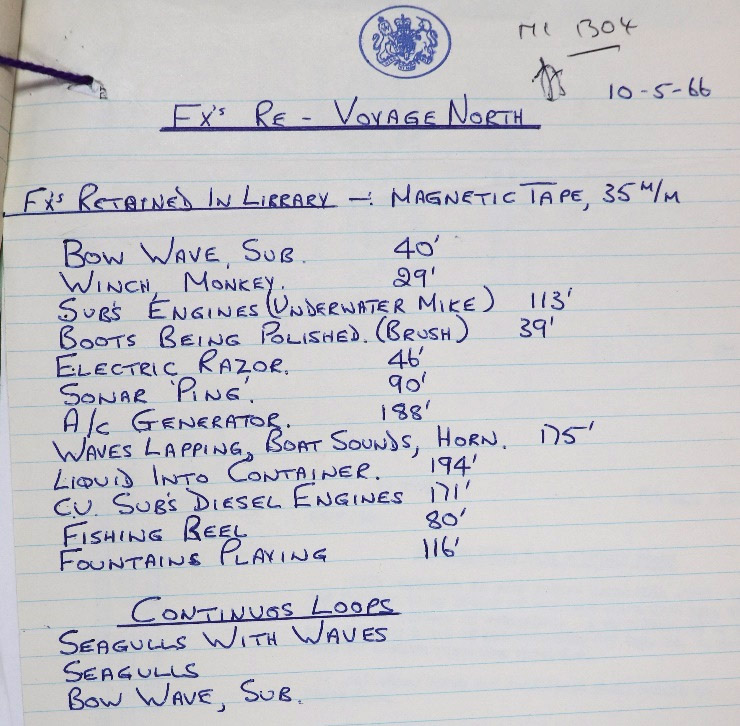

Another interesting item in the file is a list of sound effects, captured in the filming, such as the polishing of boots and a sonar ‘ping,’ which were to be retained in the library for possible use in other films.

Featuring in a recruitment film for the Royal Navy was not the last time HMS Artemis was involved in a drama though. In fact, what happened to the submarine a number of years later is worthy of a feature film in itself.

On 1 July 1971, HMS Artemis sank while refuelling in Gosport, the home of the submarine service. An account of the sinking on a BBC Making History web page explains:

‘Artemis was in Gosport for maintenance and was being made ready to leave again. She had been brought out of dock but most of the senior officers were not aboard and she was under the command of the sonar operator.

When she was alongside and taking in fuel they had run cables through the hatches into the engine-room to power her systems, and as she was ballasted down to take the fuel for her diesel engines, water came in through the hatchways which because of the cables were not closed.

Very quickly the vessel began to sink. The Duty Petty Officer David Guest went below to shut down whatever parts of the ship he could. There was a group of Sea Cadets aboard and Guest quickly cleared them out and went on making sure there was no one else there.

He found two engine-room mechanics aboard, but because of the water coming all three were unable to get out and they shut themselves into the forward compartment in the torpedo stowage area.

The ship sank to the bottom of Haslar Creek. The three men were trapped on board the sunken submarine for 13 hours but eventually managed to escape in immersion suits through the forward escape tower.’[ref]BBC Making History web page accessed 23 September 2021.[/ref]

The real-life escape has echoes of the early scene in ‘Voyage North’ where the new recruits ascend up through the Submarine Escape Training Tank in Gosport – which was presumably visible from where Artemis sank.

Three officers and a rating from Artemis were charged with negligence and tried by court martial. The National Archives’ file ADM 194/154 contains the Admiralty Board’s quarterly return of officers tried by court martial for October to December 1971, which shows that the submarine’s Lieutenant Commander was found not guilty of negligence, but two other officers were found guilty. Reports in newspapers[ref]The Times Digital Archive – Gale – The Times, 21 October 1971, accessed 23 September 2021, and British Newspaper Archive – Birmingham Daily Post, 17 November 1971, accessed 23 September 2021.[/ref] at the time also show a Stoker was found guilty of negligence, although it was noted that he had had no training for 18 years.

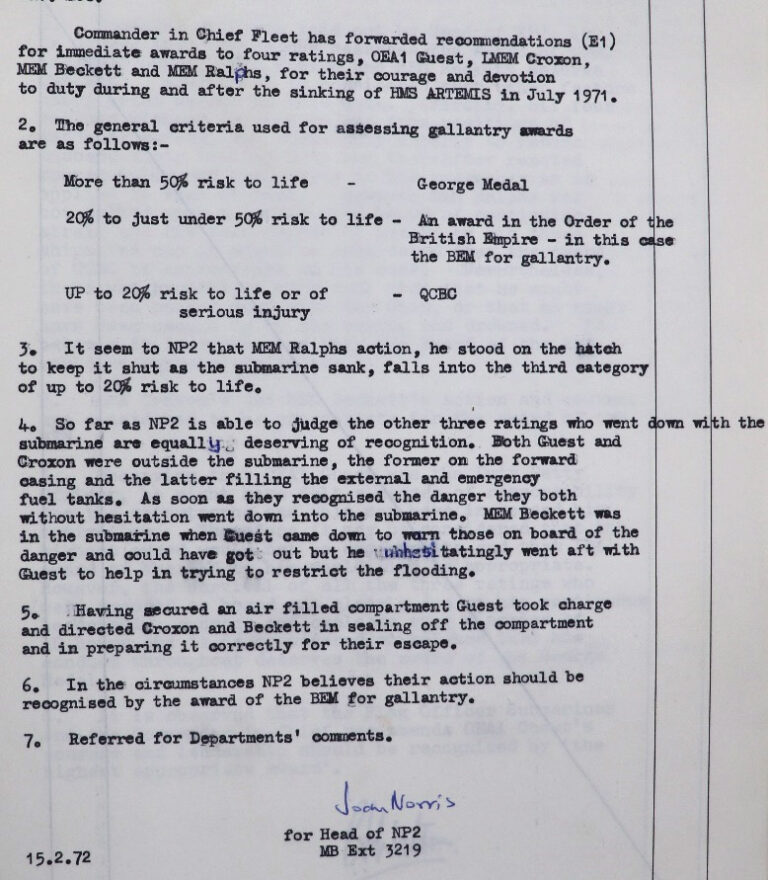

On a more positive note, The National Archives’ file DEFE 49/34 contains recommendations for gallantry awards to the four men who took action to save others as Artemis sank. The men were:

- David Guest, an Ordnance Electrical Artificer First Class aged 37, who had been serving for 19 years

- Robert Croxon, a Leading Marine Engineering Mechanic aged 23, who had been serving for seven years

- Donald Beckett, an Acting Leading Marine Engineering Mechanic aged 24, who had been serving for seven years

- Ian Ralphs, a Marine Engineering Mechanic aged 23, who had been serving for five years

The file explains that the general criteria used for assessing gallantry awards were:

- More than 50% risk to life – George Medal

- More than 20% but less than 50% risk to life – the British Empire Medal or similar

- Up to 20% risk to life or serious injury – QCBC (Queen’s Commendation for Brave Conduct)

The papers in the file show that it was initially suggested that Ralphs should be awarded the Queen’s Commendation for Brave Conduct and the other men should be awarded the British Empire Medal for gallantry. Ultimately, however, David Guest’s award was raised to the George Medal and the other men all received the British Empire Medal for gallantry. You can read the full recommendations, which mirror those in the file, in the London Gazette online.

The National Archives has been working with the Imperial War Museums and the British Film Institute to highlight our shared collections relating to the COI and to mark 75 years since it was created. Keep an eye out for more blogs focusing on other films over the next few months, and search #COI75 on Twitter.

I vividly remember going on board HMS Artemis as a 15 year old schoolboy. The boat was visiting Ipswich in The Spring of 1971 and I went as part of a school careers trip. I was immediately struck by the cramped conditions and the smell of diesel and other unpleasant odours. I could only imagine how much worse this would be would be when submerged for a long stretch. In my mind it seemed only week or so later the sub sank in Gosport. My recollection is that a diver perished while trying to rescue the trapped seamen or re-float the boat but perhaps that is incorrect?

A year later I joined the Royal Signals Army Apprentice College, – the option of operating from the back of a freezing cold Land Rover seemed preferable!

I salute the special breed of submariners.

Nick Lay

Artemis was not under the command of the ‘sonar operator’…. they are all ratings. She was under the command of the most junior officer in the crew.

When Artemis came out of the floating dock the back end was high out of the water so aft main ballast tanks vents were opened for a short time to bring the boat level for the trip across the harbour to HMS Dolphin. When she got alongside all main ballast tanks should have been blown round to empty them completely of water. THIS WAS NOT DONE.

It was common practice to have hoses and cables through hatches when alongside for supply and maintenance. This had never been a problem, no boat had ever sunk because of it. There was no other way to supply electricity from or to shore.

The Chief Stoker commenced to ‘first fill’ the external fuel tanks with sea water (including No 4 Main Ballast tank that they had configured as a fuel tank, a normal procedure) this weight of water in the tanks made Artemis lower in the water. For some reason the aft torpedo loading hatch had been opened after she came alongside (all hatches except the conning tower had been secured shut for the trip across the harbour). The harbour water level was now getting close to the lower coaming of the open hatch. A harbour boat came past and the bow wave caused the water level to spill over the coaming into the after ends. This extra weight of water in the boat put the hatch coaming below water level and the spill-over became a continuous flood. The boat was going down.

If the main ballast tanks had been blown round after tying up alongside, she would not have sunk! That was the fault of a inexperienced Submarine Officer who was not properly advised by the boats experienced Chief Stoker. Where was the Chief Stoker? He should have been onboard for the whole of the first fill and subsequent fuelling of the boat!

My Dad is in the background of a number of the training scenes, and funnily enough his surname is Ellison. I used to visit HMS Dolphin often as a little boy and often went on the subs. This brought back a lot of memories

I was on a frigate in Portsmouth at the time as a young Sublieutenant as

Officer of the Day. We were informed that a Submarine was missing so a well known process was commenced to get the frigate ready to go to sea. All was going well and I asked tye Chief Stoker when we would have steam (strange cloud like stuff!! Now history) and his blank look was followed by “in about three days when we get the boiler bricks back in the boiler” – a rich part of the learning and experience process!! Even more interesting when we discovered that it was ARTEMIS and she sank alongside at Gosport. We were berthed alongside in Portsmouth about half a mile distant!!!

Thank you Nick, Keith and Paddy for all the fascinating comments, personal memories and specialist submariner knowledge. You have added even more to the story!

I served on A boats in the sixties yes they where cramped but the comradeship made up for the conditions and I would do my time again on these great boats of their time

The letter in this article, DEFE 49/34, was signed by Joan Norris and I believe this was my mother.

I Served on A boats in the 1960s home and abroad in Singapore and was on the one that’s open to visitors now .

I Joined the royal navy in 1972 and the Artemis was still used in the submarine training sessions for new submariners as a warning of what can happen in harbour.

I served in Nuclear boats with no issues it’s a great career but not for the faint hearted.

Comradeship is the greatest asset for a ships company, it gets you through the dark days on long patrols, 12 to 13 weeks at a time.

I was at HMS DOLPHIN doing the submarine course when Artemis sank along side. The Officer of the spotted my diving qualification and ordered me to get a BA set and check the boat for open hatches. I went in the freezing water in white front, underpants and socks. (bloody cold) As I got to the gun hatch the boat began to settle and the hatch itself began to open and close as water and air alternately entered and left the boat. As the bubbles hit the surface my attendant pulled my lifeline and got me safely to the surface. I then went to the galley for a hot brew. Maybe my story is why it was mentioned that a diver nearly died earlier in this article.

From Australia

Richard Gough

My husband is in one of the photos of the rescue boat. A young John Stevenson -Stevie, RNCD. Just found the newspaper article the other day, as I was sorting out some of his papers. Sadly he died last December.

The night the Artemis sank at her moorings, I was a young member of the WRNS based at Nelson (then Victory) Barracks and working in the Rekease Office across in Portsmouth. That evening, I was at the club in the barracks with friends, celebrating my engagement to my soon-to-be husband – a seaman of HMS Rothesay, who was unfit for sea, due to a broken wrist.

Halfway through the evening, around 2100, they interrupted the music to ask for any divers to report to HMS Dolphin. It was the first we knew about Artemis’ misadventure.

An engagement celebration never to be forgotten!