The National Archives records represent the archives of the state and major courts of law. Within these records we can find out about many unexpected histories. Inspired by the recent success of the Women’s England football team, collaborative doctoral student Jessica Gregory has delved into copyright and business records held at The National Archives and newspaper collections held at the British Library, to see what they can tell us about the origins of women’s football.

Join us to learn about these early women’s football pioneers and their fight to be recognised.

– Vicky Iglikowski-Broad, Principal Records Specialist in Diverse Histories, The National Archives

This summer, England’s Lionesses have joined 32 women’s national football teams in Australia and New Zealand for the most successful Women’s World Cup to date. The England Women’s Team, unlike many other national teams, has benefitted from a recently fully professionalised home league and institutional bodies supporting the development of women’s football in the UK. Despite the current interest in the game, women’s football in the UK has suffered from a long history of suppression and neglect.

The Football Association (FA) banned women’s football for fifty years from 1921, but the FA only re-incorporated women’s football into its remit from the Women’s Football Association in 1993. The ban excluded women from the professional game and forbade women the use of its pitches. Historians have begun to highlight the popularity of the women’s game before the ban. Tales of the record crowds of 53,000 spectators at Goodison Park watching Dick Kerr Ladies against St Helens Ladies in 1920 have highlighted how popular the game might have been if given the opportunity to develop.[ref]Information on this match is available here: The Boxing Day game that changed women’s football – BBC News[/ref]

The history of women’s football, although constrained by regulation and social convention, can still be identified within The National Archives’ records even before the 20th century. In 1895, the British Ladies Football Team was causing a stir, showing Victorian spectators that women might play the beautiful game, but also facing a concerted backlash from those who thought their activities were indecent and needed to be stopped.

The BLFC

The British Ladies Football Club was formed by Alfred Hewitt Smith and captained by Nettie J Honeyball (thought to be a pseudonym).[ref]For an interesting delve into the real identity of Nettie Honeyball see: Solving the enigma of Nettie Honeyball – scottishsporthistory.com[/ref] They were supported by the president of the club, Lady Florence Dixie, whose patronage aligned with her wider championing of women’s rights. The squad had two teams which they named North and South.

The women were recruited via advertisements for players in the press. The players were described in Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper as women that were mainly from London, but some hailed from the countryside.[ref]Described in Lloyd’s Weekly, Sunday 31 March 1895, British Newspaper Archive [accessed 11/08/2023].[/ref] They were of various ages, but one Daisy Allen was a girl of between 11 and 14 years old according to different newspaper reports. She was described as a spirited player who stood out for her talent among the squad. The South team is believed to have included the first known Black British female football player, but her exact identity has not yet been determined.

Other notable players include Helen Graham Matthews who played in goal. Graham, a suffragette, had played football since 1890 and would later captain her own team called ‘Mrs Graham’s XI’. Graham’s vision for women’s football is recorded in an interview she gave in October 1895:

‘We object to being regarded in light of a joke. It will be a long time before the prejudice against the lady footballer dies away, but we want the public to observe our mastery of the game, not to come see us on account of the novelty… my firm opinion is that women can, if they are robust and strong enough physically, acquire a fair proficiency in Association.’

Helen Graham Matthews quoted in ‘The Sketch’, 9 October 1895[ref]The Sketch, 9 October 1895, p.47, British Newspaper Archive [accessed 11/08/2023].[/ref]

The squad approached football in earnest and struck back at those who thought it was a publicity ploy. The squad trained prior to playing in early 1895, training twice a week from lunch until dusk, and they received blackboard lessons from Millwall players.[ref]As described in the Tamworth Herald, 12 January 1895, British Newspaper Archive [accessed 11/08/2023].[/ref]

The two teams played each other in a series of exhibition matches as they toured the UK in 1895. Among some of the places they played were Crouch End and Greenwich in London, as well as Hartlepool, Burnley, Montrose in Scotland and Belfast in Northern Ireland. The games aroused great curiosity, with 10,000 spectators attending their first match at Crouch End.

Kits, boots and Rational Dress

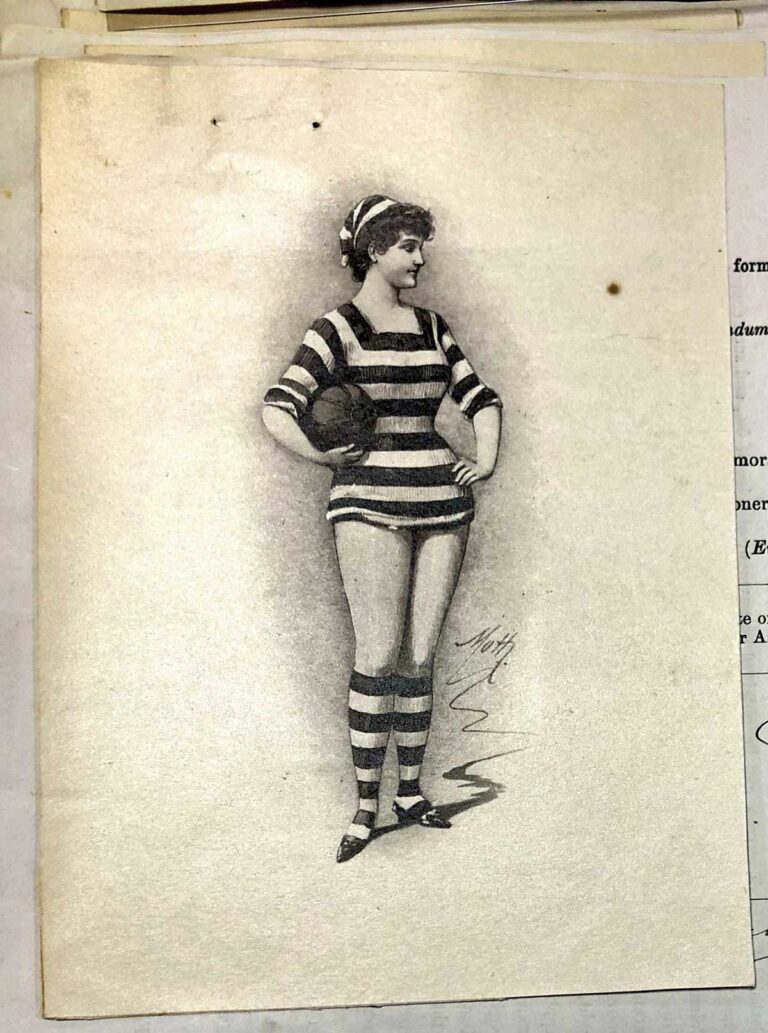

Much of the curiosity surrounding the British Ladies Team focused on what exactly they would wear to play football. Much of the press coverage from the time mentions the expectations of women’s dress and the impracticalities of playing football without being seen as displaying oneself indecently. The focus on dress seemed to be two-fold, both in outright disgust at the practical garments on display and a fetishisation of the women wearing less constrictive clothes than usual.

The following drawing of a female football player plays into certain fantasies of femininity that would certainly have been condemned if really witnessed on the pitch:

Instead, the issue of dress was approached rationally. Shirts were loose fitting to allow for movement, but conservative in that they covered the body to the wrists. Instead of impractical dresses the team wore knickerbockers – a baggy short-trouser that was tucked into long socks. The knickerbockers, though controversial in that they were essentially a trouser, were flowing and baggy enough to remind spectators of a skirt. On top of this the women wore shin pads for protection and caps on their heads throughout the matches.

The president of the club, Lady Florence Dixie, was particularly passionate about the use of practical clothing by the team. She believed in the reform of Victorian styles of dress in a movement called the Rational Dress movement. She decried ‘that hydra-headed monster, the present dress of women’ for its restrictiveness.[ref]Penrith Observer, 19 February 1895.[/ref] The team may have adapted their dress for practical measures, but they could not wear the same kit as the men. However, one item with which the team did match the men was with their boots and shin pads.

‘The dangers of lady football!’

There was much enthusiasm for the British Ladies Football Team as they travelled the country. Some accounts describe much cheering and crowds of people swamping the field at full time. The abiding media reception, however, appears to be one of confusion and derision. Crowds were often described as heckling and mocking. Although some writers expressed surprise at some of the skill of the women, press coverage was predominantly sneering, with most professing the phenomenon to be a passing fad. The team’s association with women’s suffrage through Florence Dixie, and ‘the new woman’ archetype (a notion of an independent and convention-breaking woman that embodied new feminist ideas), meant that many journalists were keen to point out the shortcomings of women attempting traditionally male activities.

Some protests were practically extravagant. The Archdeacon of Manchester referred to the British Ladies’ visit as a ‘disgrace’ and stated that such displays should be disallowed on the grounds of morality.[ref] Quoted from Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 3 December 1895, British Newspaper Archive [accessed 13/08/20023].[/ref] Medical authorities also condemned women playing the game and offered their own reasoning for why the practice should have been stopped, which stated football was detrimental to the female biological body:

‘It is impossible to think of what happens when the arms are thrown up to catch the ball, or when a kick is made with full force, and misses, without admitting the injury which may be thereby produced in the inner mechanism of the female frame. Not can one overlook the chances of injury to breasts… in regard to the proper use of the breast, however, in the rearing of infants, there can be no doubt of the deleterious influences…’

British Medical Association, 1894[ref]British Medical Association quoted in Dundee Evening Telegraph, 10 December 1894, British Newspaper Archive [accessed 13/08/2023].[/ref]

Ongoing challenges – and spirit

The controversies around women’s football that emerged in 1895 would not dissipate even as its popularity grew through the early twentieth century.

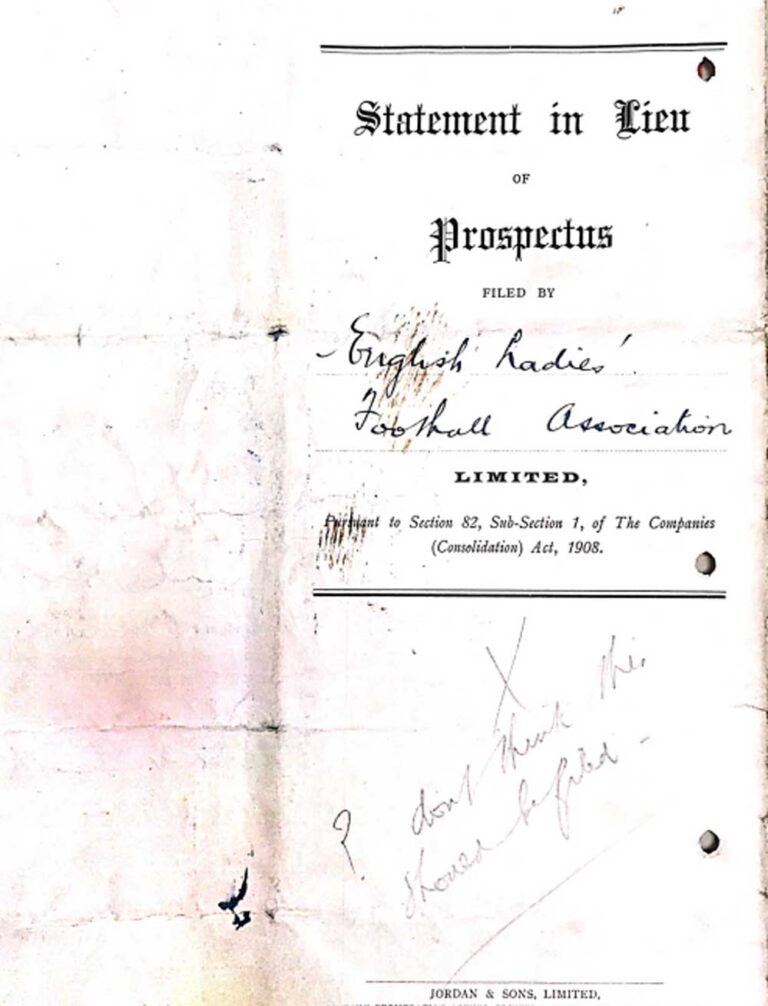

The exhibition matches bought women’s football to pitches around the country and to the attention of many those who would never even have considered women’s football a possibility. However, accusations that playing the game was antithetical to a woman’s purpose and a danger to their health continued. The FA ban in 1921 effectively condemned the women’s game to obscurity, but the desire to play never ceased. The FA has since apologised for the ban. The document below perhaps sums up the conflicts that have blighted women’s football in the UK:

The English Ladies’ Football Association (ELFA) was set up in 1921 as a response to the ban.[ref] English Ladies Football Association – Wikipedia[/ref] This attempt to keep the game going reflects the spirit of those involved. Though ultimately short-lived, the ELFA stood as a precursor to the Women’s Football Association (WFA) that would be set up in 1969. The WFA took up where the British Ladies and The English Ladies Football Association had left off, instigating the process of re-igniting the sport and setting many new generations of Lionesses on their way into the beautiful game.

Jessica Gregory is an AHRC-funded PhD student collaborating with The National Archives and The University of Kent. Her work examines evidence of censorship of sexual print in government records.

We support doctoral students across a range of disciplines by providing supervision and access to research facilities.

Were there any ladies called Metcalf/e in the early teams?

Very interesting and topical article, thank you. Please note that the FIFA World Cup has been jointly hosted by Australia and New Zealand. I attended two matches in Wellington and the atmosphere was awesome. I’ll be cheering for the Lionesses at the weekend.

Thank you very much for this. We’ve updated that information now.

It’s not true to say that women were banned from professional football and it’s misleading to suggest women’s football was attracting large crowds. Large crowds did turn out for a few charity matches but they didn’t turn out for other games, all the iterations of women’s football between 1895 and 1921 going bust. The issue of payment and monies missing from the charity matches was also a concern. Men were banned from payment during the war, so it would hardly do for women who didn’t fight to be paid.

A very good article but Emma Clarke was neither Black nor mixed heritage. There is a woman in the back row 2nd left who looks like she could be mixed heritage (I have viewed the photograph at the National Archives) but if she is indeed Black or mixed heritage she is not Emma. Research shows that all of Emma’s ancestors were white British. The Football Association has recognised this significant doubt by removing Emma’s name from its website under the entry ‘Ten Key [Black] Figures From The English Game,’ she was replaced by Hope Powell. The Scottish Sport History website also casts doubts on Emma’s claims under an article entitled ‘A Case of Mistaken Identity.’ Jean Williams’ definitive work ‘The History of Women’s Football’ also disputes the claim that Emma Clarke was the first Black women footballer. This is not to say necessarily that the women in the back row 2nd left was not Black or mixed heritage but, if she was, her name was not Emma Clarke and her true identity remains to be discovered.

Thank you very much for your comment. We have now updated this blog to express the uncertainty around the identity of the woman thought to be the earliest known Black British female football player.

Does anyone know whether the Dick Kerr company has any archives anywhere?

I am on the trail of Alice Bamber, who worked at a Kerr Factory in Hackney – she was a ‘munitionette’ and a footballer.

I am somehow hoping someone has photos of their great great granny in their attic in her football kit!

What a great article – thank you.

I’ve been puzzled for some time about the British Ladies Football Team tour of Wales, 1895 and 1896. The towns they played in North Wales were Conway, Llandudno and Flint – why not Wrexham, where the Welsh Football Association was founded? Were they refused permission?

There’s nothing in the WFA minutes in the National Archives of Wales, I can’t find anything in the press. It’s a Mystery.

Great blog and fabulous photos… COPY 1 is the collection that keeps on giving!

Hi, looking at your two photos of the North and South teams can I ask why there are not 11 players. Did they play with only 9?