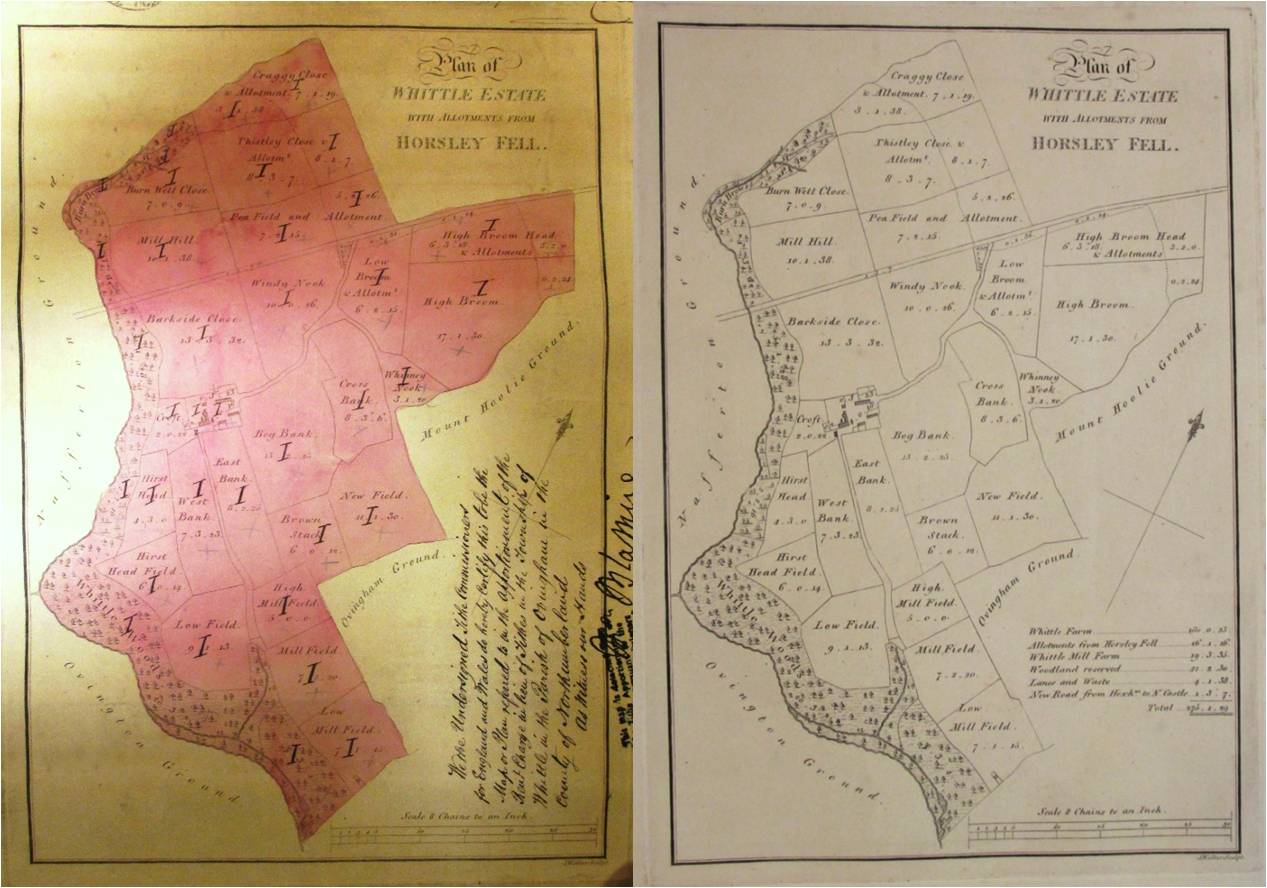

Spot the difference: the map on the left (catalogue reference IR 30/25/476) is a customised version of the map on the right (catalogue reference MPI 1/162 no 17).

Like most archivists, librarians and curators, I have some favourite items among the collections that I work with. Regular readers of our blog may recall that I have used some of my posts to write about a selection of the maps and other records that I particularly like.

Today’s post is not about one of my favourite records but about one of my favourite recordkeeping techniques. This consists of taking a pre-existing map and customising it for a new purpose.

Making an accurate map from scratch takes time, skill, care and often considerable expense. In many cases, people who needed a map for a specific purpose have decided that re-using an old map was more efficient – and just as effective – as making a new one.

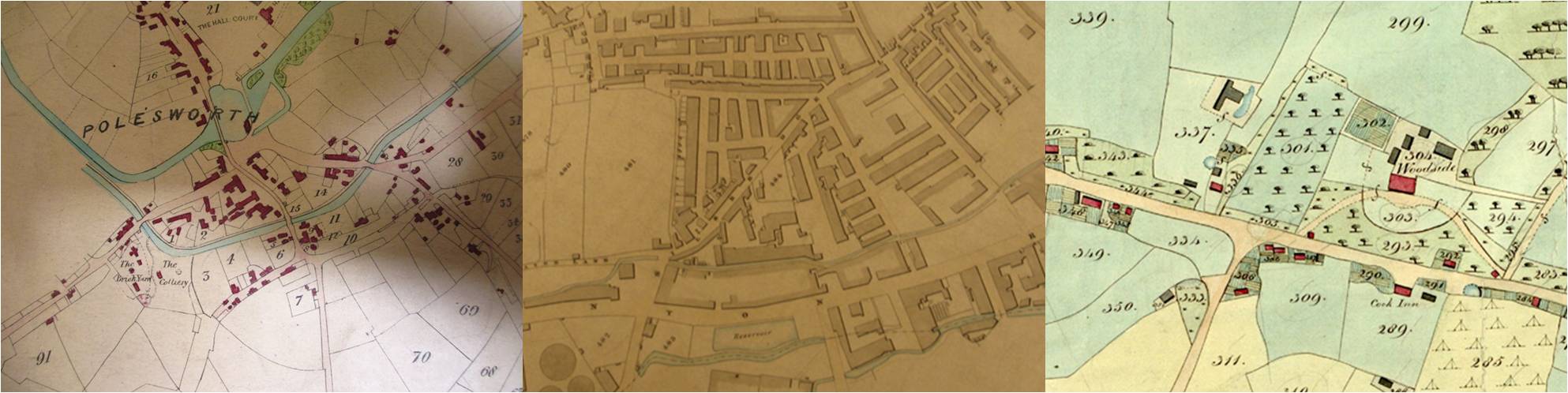

The simplest method of customising a printed map is to annotate it by hand, adding to or altering the printed information. Map curators often refer to these annotations as ‘manuscript additions’. Here at The National Archives, we have a very large number of printed maps with manuscript additions because government bodies have often made use of this technique in their recordkeeping.

Recently, I was doing some research for a talk that I am giving at a conference soon when I came across two copies of the same printed map among different sets of records. One is annotated and the other is a ‘clean’ copy.

The plain copy [ref] 1. MPI 1/162 no 17. [/ref] is a printed estate map of land in Whittle, in Ovingham parish, Northumberland, dating from 1805. It comes from a large volume of maps of estates in the north of England belonging to the Greenwich Hospital. [ref] 2. For more information about records of the Greenwich Hospital, see this section of Discovery, our catalogue, and our research guides to Royal Navy officers’ pensions and ratings’ pensions. [/ref]

You may wonder why an institution based in the south-east of England owned land so much further north. The answer is that the government had confiscated these estates from the descendants of the 3rd Earl of Derwentwater – who had been executed for taking part in the Jacobite Rising of 1715 – and given them to the Greenwich Hospital to administer. [ref] 3. Our catalogue includes more information about the Forfeited Estates Commission and its records. [/ref]

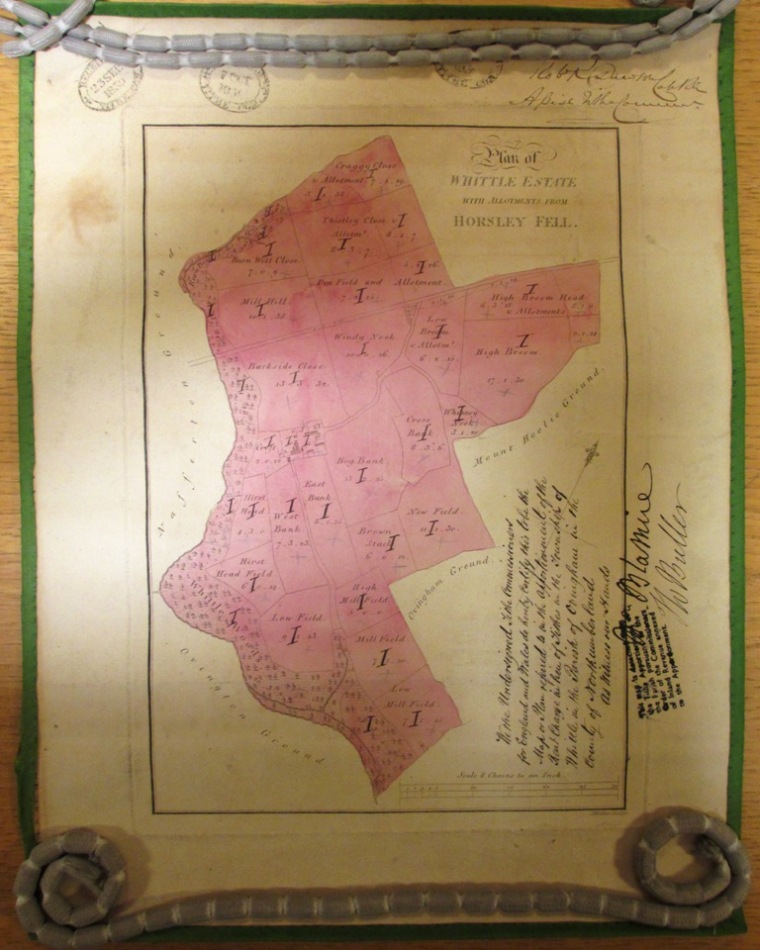

This copy of the estate map was annotated for the Tithe Commissioners in 1839 (catalogue reference IR 30/25/476).

The annotated copy of the same map [ref] 4. IR 30/25/476. [/ref] was used as a tithe map in 1839.

The history of tithes is rather complicated. They were an ancient form of church tax, originally paid in kind, as a proportion of the goods produced by farmers. By the early 19th century, the system had been reformed unevenly in different parts of England and Wales and was widely seen as anachronistic and unfair. To cut a long and complex story very short, the tithe survey was carried out to aid a more sweeping reform to the system of payments.

The apportionments and related maps created as part of this survey are now very widely used by researchers, including family and local historians. They contain information about the use of land and about the people who owned and occupied it. Most of the records date from the late 1830s and early 1840s, but some were made later.

Tithe maps are very diverse in size, scale and general appearance. Many were entirely new maps hand-drawn especially for the survey, but copying or re-using an existing map was allowed if a suitable one already existed. Several maps of the Greenwich Hospital’s estates were used in this way.

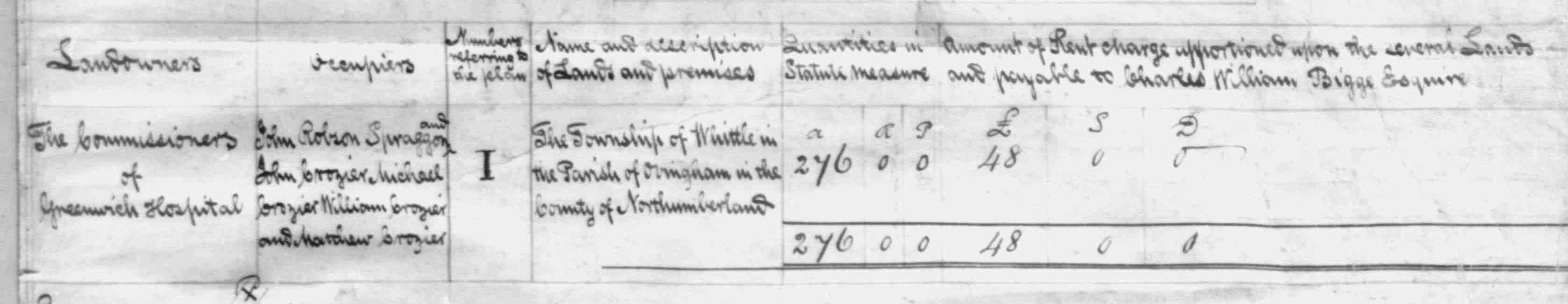

A detail from the tithe apportionment (catalogue reference IR 29/25/476). This includes the names of the landowner and occupiers.

The individual properties covered by the tithe survey were numbered. This numbering system is used to connect the areas marked on the tithe maps to written information in the apportionments. Our example here is rather unusual: all of the plots of land have the same number: the Roman numeral ‘I’ (which means ‘1’). This is because the same landowner – the Greenwich Hospital – owned all of the tithable land in Whittle. There is only one entry (also numbered I), in the tithe apportionment for Whittle. [ref] 5. IR 29/25/476. [/ref]

This is just one example of an annotated map. I have sneaked some other examples of this recordkeeping technique (ranging from the 16th century to the 20th century) into previous blog posts. I’m sure that I will share some more with you in future posts too.