Hannah More was a Christian activist and philanthropist. Her sociable life in Britain’s major social centres, London and Bath, enabled her to use her closeness to the bluestocking circle and later her membership of the evangelical group, the Clapham Sect, to embark on crusades against poverty, the education of women and the evils of slavery.

In celebration of Women’s History Month, The National Archives has reproduced an extract on Hannah More from The Digital Encyclopedia of British Sociability in the Long Eighteenth Century (Digitens). The National Archives is a partner in Digitens, a project funded by the EU’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme. Focused around the theme of British sociability, the encyclopedia is open access and written by 18th-century scholars from various fields. This extract is adapted from the entry on Hannah More by Professor Annick Cossic at the Université de Bretagne Occidentale.

Hannah More (1745-1833) used her pen and her literary talents to promote four main causes: the reformation of manners, the abolition of slavery, the education of women and the alleviation of poverty. Having started as a provincial schoolteacher living in Bristol and educated in her father’s school, she soon became the author of a play, ‘The Search after Happiness’, which, first published locally, was republished in London where it won her public recognition. There, thanks to her friends’ letters of introduction, she rubbed shoulders with the literati of the bluestocking circle, dominated by Mrs Montagu of whom she quickly became a protégée. It is undoubtedly her status as a playwright that enabled her to strike a lifelong friendship with David Garrick and his wife Eva, and to lionize Samuel Johnson and Horace Walpole. What has been called ‘the Complicated Temptation of the theatre’ reveals a tension at the heart of her early life between indulging in the pleasures of sociability, albeit literary sociability, and the seriousness of her mission, i.e. the reformation of society through philanthropy.

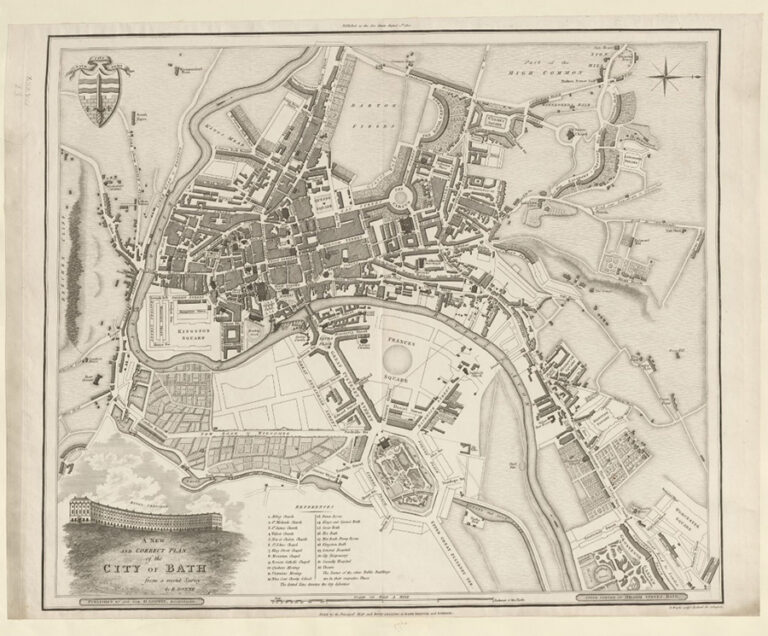

Three cities, as renowned sociable spaces, shaped More’s personality: Bristol, where her literary career was launched; London, to which she made regular trips after her prospects of marrying a wealthy squire failed to materialize; and Bath, where the five More sisters bought a house on Great Pulteney Street and spent the winters of the 1790s. She led a very sociable life there, ‘thriving on company and conversation, especially with like-minded people who managed to combine high spirits and seriousness in a blend similar to her own.’ It is in Bath that she met William Wilberforce (philanthropist and abolitionist) and that the two conceived a scheme to improve the condition of the Mendip labourers.

At first, the cement of these new relationships was the sharing of literary interests. More also wrote poems, essays and stories, and her celebrity fed on that of the other members of the bluestocking circle. Conversely, as part of the second generation of bluestockings she helped maintain it in the limelight. Even in the case of her friendship with Wilberforce, it is literature that brought them together and he acted as literary adviser.

Intellectual sociability in the second half of the 18th century observed the rituals that had by then been established, with its round of breakfasts, parties, card-playing, the central role of the tea-table, and a conversation where books – they could be exchanged – health matters and politics featured prominently.

Yet, despite the benefits of urban literary sociability, More was never blinded by the dazzling lights of the city. Her visits to London grew less numerous as the years went by and, as for Bath, she had always ‘hated’ the place. Her somewhat forced spinsterhood made her free, thanks to her recent financial independence, to set up her own social network and she used her London celebrity to create an original model of sociability that was essentially philanthropic. In so doing, she opened up new vistas for women and redefined their role in society. She firmly, through her actions, departed from the Georgian ideal of womanhood and played a pioneering role in outlining the contours of a Victorian one: ‘she was part of the new Puritanism steadily gaining ground in the wake of the French Revolution which urged women to turn their backs on the allurements of the ball and the pleasure garden and find their vocations in the duties of home and the expanding world of philanthropy.’ This was a message delivered in her works Coelebs in Search of a Wife (1809) or in Hints towards Forming the Character of a Young Princess (1805): women should make themselves useful.

The new world of philanthropy that emerged in Britain had a strongly religious dimension and More moved increasingly towards a sociability of the heart while simultaneously maintaining a sociability of the mind. She claimed that her aim was to be a good Christian, and contested the allegation of Methodism. Yet she shared with Wilberforce and the other members of the Clapham Sect, who were all Evangelicals, together with an unflinching faith, great dissatisfaction with the Anglican clergy, absent from their parishes and seemingly indifferent to the plight of the poorest part of their congregations. In many instances, it is ‘classical’ sociability that made her acquainted with the evils of the society of her times.

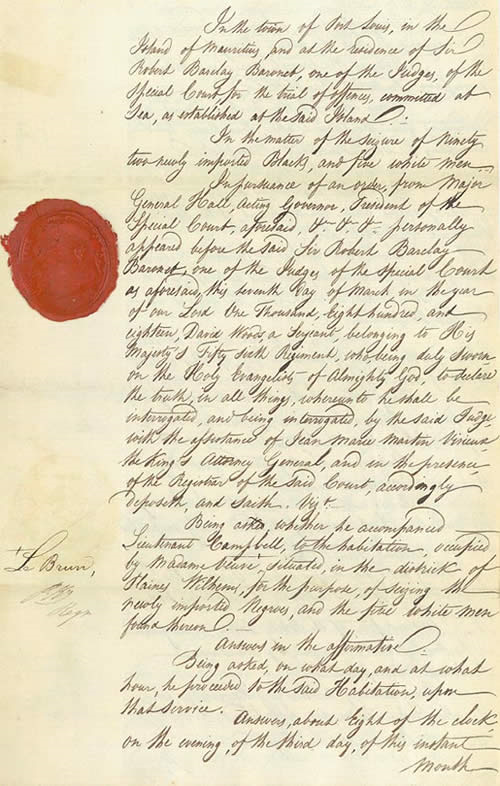

One of her major fights was the fight against slavery and the abolitionists’ crusade became hers thanks to a dinner party in 1776. She remained convinced that the pleasure principle – identified by Georg Simmel as a distinctive feature of true sociability – should not be eradicated from charitable ventures. She thus organized feasts in her Mendip schools, hybrid events combining revelry and charity.

Most of the letters that she wrote, in particular those sent to Wilberforce, testify to the subordination of mundane sociability to the sociability of the heart and to religious sociability. The correspondence with Wilberforce revolves around schools, charity or religion: their friendship thus followed the same pattern as their lives, i.e. an ever-growing involvement in philanthropic schemes. But More was also adamant that charity must not be an excuse for a tepid faith and she outlined her views on philanthropy in Thoughts on the Importance of the Manners of the Great to General Society. She firmly dissociated ‘mechanical charity which requires springs and wheels to set it agoing (from) real Christian charity (that) must not supplant faith’. The Thoughts simultaneously condemns what More sees as the excesses of Georgian sociability – Sunday concerts, Sunday walks in public gardens, the blurring of the frontier between right and wrong in polite conversation – and reiterates the importance of ‘association,’ i.e. sociability.

Convinced that Georgian sociability threatened the moral fabric of the nation, Hannah More embarked on a crusade for the reformation of manners. The Mendip schools that she set up, with the active contribution of her sisters, stemmed from a desire ‘to instruct the poor, to inform the ignorant, and to reclaim the vicious.’ More saw her Cheddar School as a sort of ‘Botany Bay expedition’ and targeted the children, but also their mothers who could attend evening classes. As for her Sunday schools, ‘their modest agenda’ included ‘the inculcation of the socially desirable virtues of punctuality, cleanliness, and honesty.’

More understood that the success of the scheme depended on the participation of the Great, both men and women: she particularly appealed to the latter, because she saw them as enjoying a specific talent, that of ‘influence’. By trying to reform the poor she simultaneously improved the rich: ‘Reformation must begin with the Great or it will never be effectual. Their example is the fountain from whence the vulgar draw their habits, actions and characters.’

As she grew older, More moved away from sociable encounters and gatherings to a reclusion at home. But Barley Wood, where she spent many years, turned out not to be a hermitage, and she complained: ‘I never saw more people known and unknown in my gayest days. They came to see me as the witch of Endor.’ More’s attitude to retirement was fraught with ambiguity, since she both yearned for it and resented it.

Nonetheless, in spite of her cautious approach to reformation, based on sympathy, not on imposition, she was perceived by the clergy and the local gentry as an agent provocateur whose main tool, the printed word, was hard to counter. The new type of literature for the poor that she created was a key agent of the dissemination of her ideas. The success of the Cheap Repository Tracts in particular was unrivalled, thus enabling her to create another, wider, network, made up of readers – she had identified ‘three great classes, the fashionable, the religious, the political’ – and contributors. This popularization of ideas, many of them shared by the Clapham Sect, antagonized the Latitudinarian Anglican clergy and More’s schools came under attack, like the Blagdon one that became the object of a national controversy. At the other end of the political spectrum, radicals like William Cobbett, who dubbed her ‘the old bishop in petticoats’, and the supporters of the French Revolution saw More’s philanthropic sociability as reactionary.

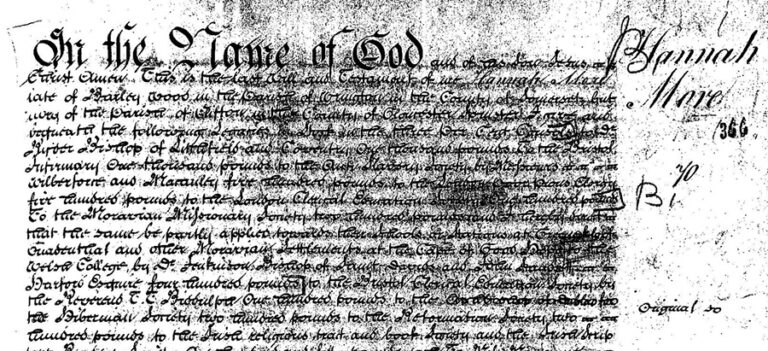

Through her works, Hannah More outlined a new role for women as prime agents of social and moral reformation. She instrumentalized the sociability of the upper classes to create a new model in which private individuals and the state collaborated. She knew a number of failures due to the contradictory directions of her action – on the one hand encouraging women to embrace charitable causes, but on the other hand never actually challenging male domination, as ‘true’ independence was that of the mind. Her philanthropic sociability announced the Victorian era and was not deprived of smugness. She redirected sociability towards the Christian ideals of benevolence – doing good – and of charity, and put centre stage the idea of the mission that was to seduce so many British people in the 19th century. She also contributed to a decentring of sociability from London to Bath or Bristol and embodied a new ideal of womanhood by impersonating the philanthropic unmarried intellectual. In her will, she donated money to a list of charitable institutions, a further proof of her dedication to the philanthropic cause.

This extract is adapted from Annick Connic, ‘Hannah More (and philanthropic sociability)’, The Digital Encyclopedia of British Sociability in the Long Eighteenth Century [online], URL: https://www.digitens.org/en/notices/hannah-more-and-philanthropic-sociability.html.

The full references for the works and quotes used in this blog can be found on the encyclopedia page.

Photo/image credit: Girton College, University of Cambridge