In the latest of our #Readeption550 blogs, Dr Hannes Kleineke from the History of Parliament explores the concept of royal pardons in the medieval period, and Henry VI’s Christmas pardon of 1470-71.

Those watching in bemusement, as every year before Thanksgiving the President of the United States pardons a turkey from being slaughtered and eaten might be forgiven for failing to notice that what they see played out ritually is a display of sovereign power with medieval roots.

The power to pardon (albeit men and women, rather than a melancholy fowl) was a prerogative prized by the medieval and early modern rulers in equal measure. The late medieval kings of England pardoned offenders in huge numbers. There were general pardons of all offences, sometimes limited to those committed before a given date; special pardons relating to a specific offence or offences, sometimes in the nature of political indemnities; and pardons of outlawry, designed above all to keep the cogs of the judicial system turning.

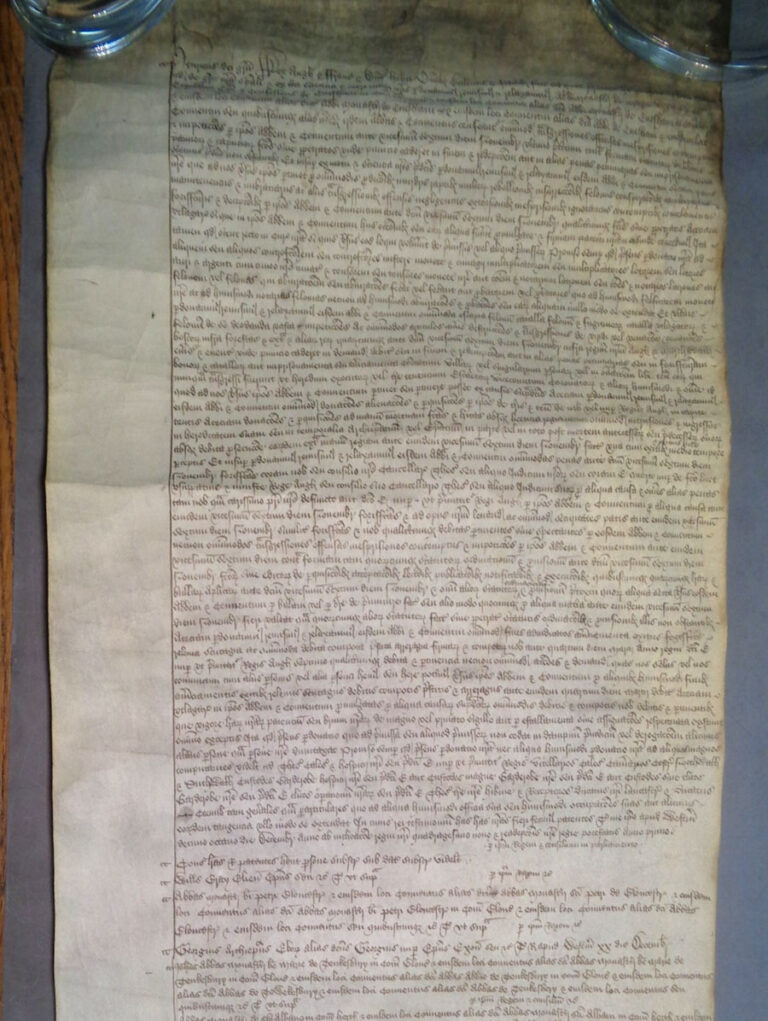

What all of these had in common was that the power to grant them was personal to the monarch – the pardon being granted so that the written exemplification would state, ‘of the King’s special grace, of his certain knowledge and his mere motion’.

‘de gracia sua speciali et ex certa sciencia et mero motu’

‘of the King’s special grace, of his certain knowledge and his mere motion’

The late 14th century saw an important step in the evolution of the practices of royal pardoning when King Edward III, to mark his 50th year on the throne, announced a general pardon that covered a broad range of offences committed before a set date, which all comers might sue out of Chancery on payment of a fine for the issue of their personal copy. Under Edward’s successors the issue of such general pardons became increasingly common, and the troubled reigns of Henry VI and his successors saw repeated proclamations of fresh pardons, often in response to particular political crises. In the 16th century, finally, the regular issue of general pardons became an integral characteristic of Tudor law enforcement.

From the second half of the 14th century Parliament had increasingly become the stage on which grants of pardons were announced, and the Commons in Parliament were accorded a distinctive role as petitioners for the King’s mercy. Nevertheless, while general pardons were sometimes granted by way of an expression of royal favour following a grant of taxation on the part of the Commons, the Crown was at pains to emphasize its absolute discretion in the exercise of the monarchical prerogative of mercy. In 1531, Henry VIII openly clashed with the Commons, some of whom had objected to a bill granting a limited pardon of certain offences to the clergy. Not without justification, the King took the Commons’ intransigence as a direct attack on his prerogative, and refused to grant any pardon under pressure.

While in administrative terms copies of general pardons were above all tools for their individual recipients to bring an end to Crown prosecutions against them, the proclamations of their grants had a wider importance in signifying the King’s intent to pacify his realm and heal divisions. Thus, in the crisis years from 1468 to 1470, Edward IV announced two separate pardons within a few months of each other, and with Henry VI’s restoration in October 1470 a fresh grant could reasonably be expected.

This, it seems, was indeed forthcoming in the final days of the autumn session of the Readeption Parliament. Although the records of the parliament are largely lost, it is reasonable to suggest that the pardon was first announced during the assembly. Moreover, while there continues to be debate over the extent to which Henry VI was capable of personally exercising his royal powers at any time during his reign, it seems clear that by 1470, following years of exile and captivity, he had reached a new low point.

Thus, the notes on the pardon roll recording the authority on the strength of which the individual letters had been issued read – uniquely in the history of late medieval pardoning – ‘by King and Council in Parliament’ (‘per Regem et Consilium in Parliamento’), rather than ‘by the King himself’ (‘per ipsum Regem’), as was customary: a limitation of this most personal of royal prerogatives otherwise unheard of.

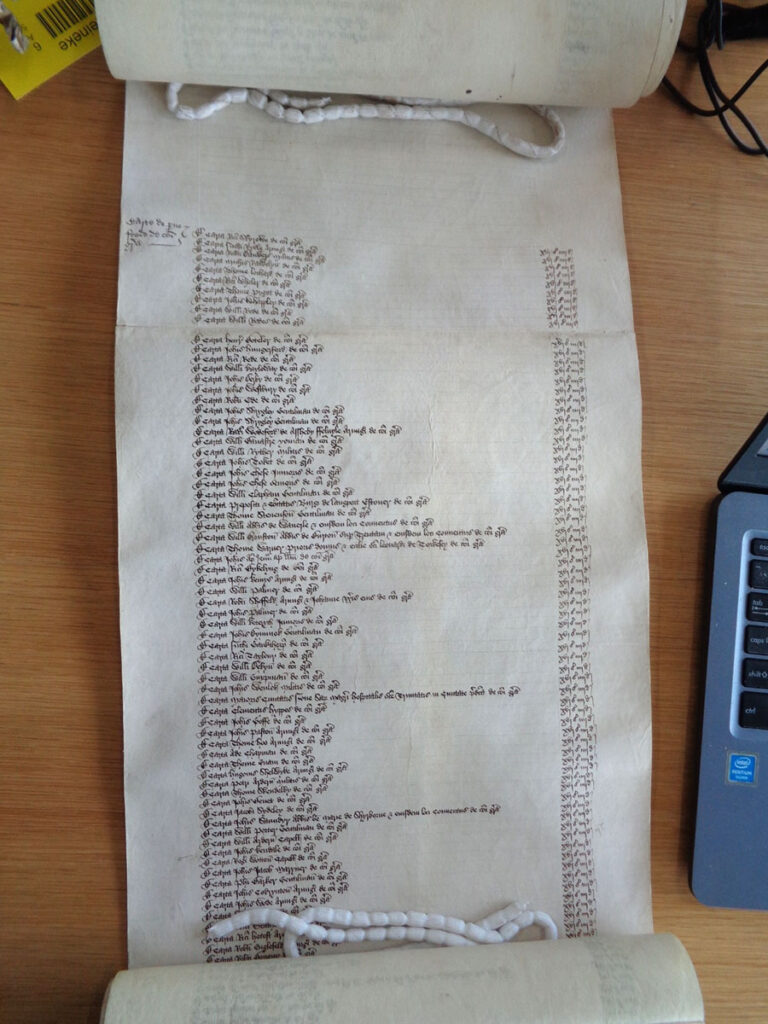

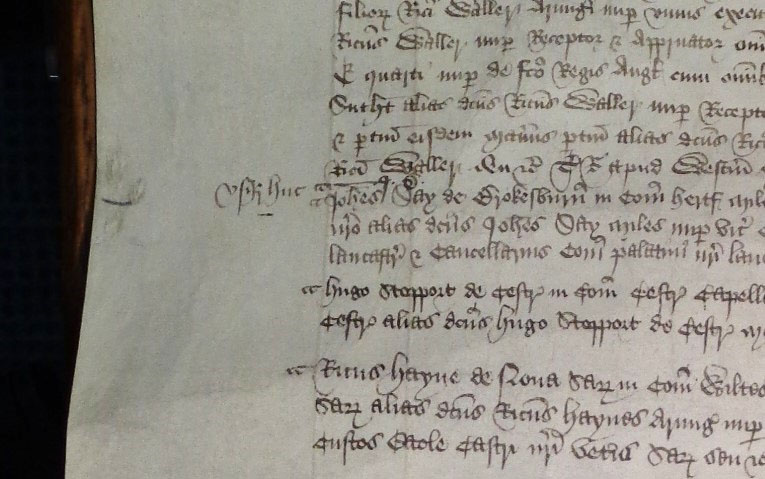

The pardon rolls (series C 67) – separate rolls recording exclusively copies of general pardons – were compiled in parallel with the principal series of enrolments of letters patent (series C 66), which included special pardons as well as pardons of outlawry, and were not the only records kept in connection with the issue of the pardons. In parallel, the keeper of the hanaper (the chief financial officer of the royal Chancery) also recorded the payments taken for each individual letter of pardon, and it is a mark of how well-oiled a machine the late medieval Crown’s writing office was that the change of keeper left little trace in the record. A mere marginal note on the Pardon roll indicates the changeover from John Davyson to John Walter on or after 22 January 1471.

This aside, the pardon followed the standard model of those that had been issued during Henry VI’s first reign. It covered a broad range of offences committed before the opening day of the 1470 Parliament, as well as any moneys owing to the Crown before the beginning of the seventh year of Edward IV’s reign (4 March 1467). Where Edward IV’s pardons had expressly excluded a selection of named opponents, there were no individual exclusions from the Readeption pardons – a clear expression of just how badly the regime needed to reconcile its former enemies.

Whatever the King’s personal role in agreeing to the pardon, it began to be issued in the final week of Advent, a day before the likely date of the assembly’s prorogation, allowing the members of the Commons to take the news home into the provinces. A small number of pardons were issued before the end of the Christmas festivities, most of them to prelates and heads of religious houses (including the archbishops of York, the bishops of Ely, London and Hereford, and the abbots of Westminster, Cirencester, Gloucester, Tewkesbury, Malmesbury, St. Albans and Abingdon), but it was during the second session of the Parliament in January and February 1471 that the great bulk of pardons – some 200 copies – were sealed.

In total, 304 copies of the pardon were issued, and it is tempting to speculate whether the rapid decline in the numbers sued out after the third week of February owed something to rumours of Edward IV’s impending return, which would render futile the expense of purchasing a pardon under Henry VI’s seal. That such rumours were rife is indeed suggested by the decision of the government during Lent to round up suspected Edwardian loyalists and place them in the Tower, as a Cologne merchant then in London reported to his friends back home.

The dubious honour to have sued out the last of Henry VI’s pardons thus fell to the London haberdasher William Bacon, who procured his letters on 20 March 1471. By that date, Edward IV was back in Yorkshire and on his way south, and just three weeks later he would enter London in triumph.

Hannes Kleineke is the Editor of the 1461-1504 Commons section of the History of Parliament. He is the editor of ‘Pardon Rolls of Edward IV and Henry VI, 1468-1471’ published by the List & Index Society, which can be purchased online here, and provides details not just for those individuals who purchased a royal pardon, but also their various aliases, making it an invaluable resource for local and family history. The rolls for 1471-1483 will be published by the List & Index Society at the start of 2021.

Further reading

Helen Lacey, The Royal Pardon: Access to Mercy in 14th-century England (Woodbridge, 2009)

K J Kesselring, Mercy and Authority in the Tudor State (Cambridge, 2003)

Susanne Jenks, ‘Exceptions in general pardons, 1399–1450’, The 15th-century XIII: Exploring the Evidence ed. Linda Clark (Woodbridge, 2014), pp. 153-82

Pardon Rolls of Edward IV and Henry VI, 1468-1471 ed. Hannes Kleineke (Kew, List and Index Soc., 2019)