Historical documents are precious items, but their existence can be precarious. This was emphasised to me when an archival surprise radically altered the scope of a project that began as a Master’s thesis and resulted in my book ‘Glubb Pasha and the Arab Legion: Britain, Jordan, and the End of Empire in the Middle East’ (Cambridge University Press, 2017).

My original intention was to examine the causes and consequences of King Hussein’s dismissal of British officer Glubb Pasha from his role as commander of the Jordanian army – the British-financed Arab Legion – on 1 March 1956.

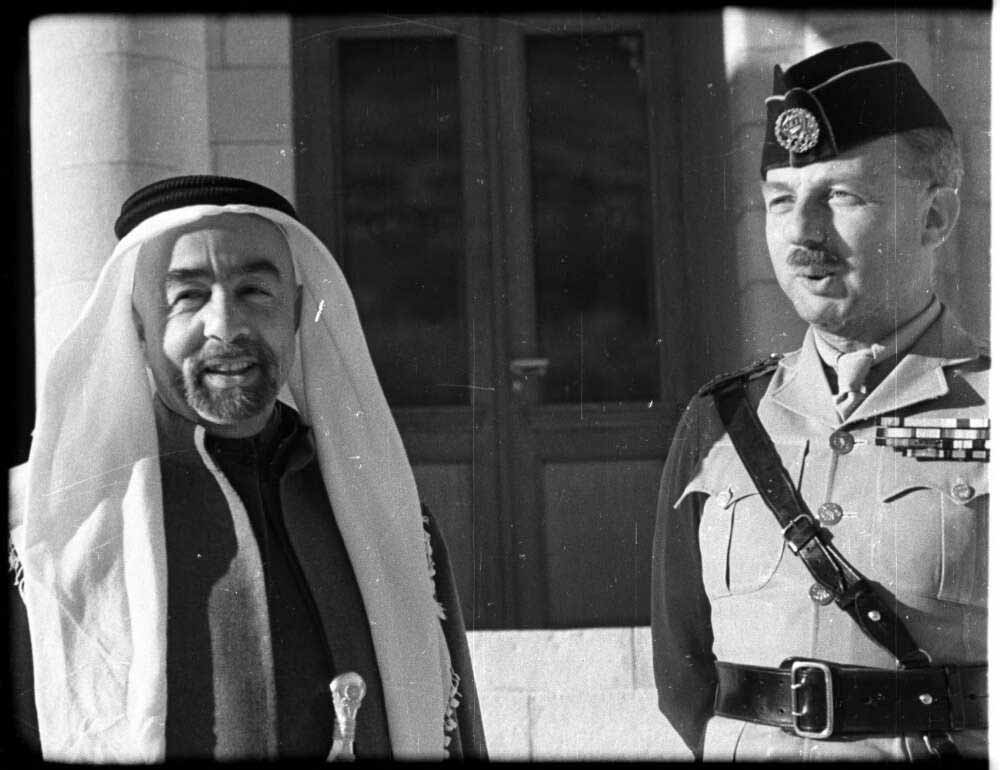

Amir Abdullah and Glubb Pasha, 1940-46 (image credit: Frank Hurley, Hurley Negative Collection, National Library of Australia, PIC FH/5886)

To that end I sought out Glubb’s private papers at the Middle East Centre Archive at St Antony’s College, Oxford, where 14 boxes of material, pre-selected by Glubb, were deposited after his death in 1986. Given the paucity of references to this collection in the secondary literature, I travelled more in hope than expectation. But my hope was richly rewarded, as a major new accession of Glubb’s papers – more than 100 boxes – had recently been deposited.

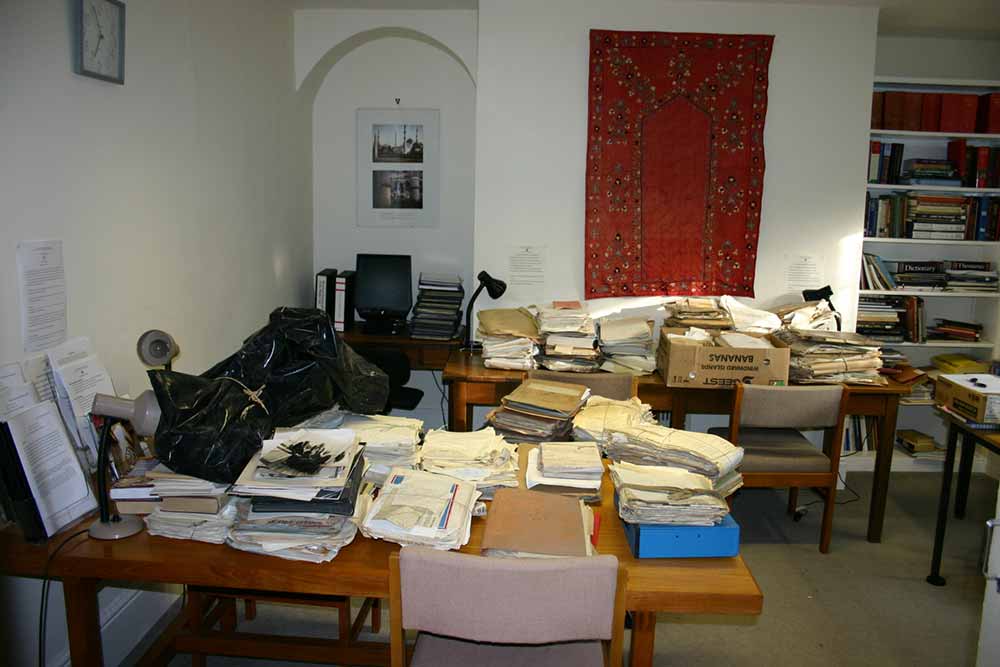

- The Glubb collection arriving at the archive, May 2006 (photo courtesy of the Middle East Centre Archive, St Antony’s College, Oxford. GB165-0118 Glubb Collection)

- The Glubb collection being unpacked, May 2006. (Photo courtesy of the Middle East Centre Archive, St Antony’s College, Oxford. GB165-0118 Glubb Collection)

When the Glubb family home was cleared after the death of Glubb’s widow in 2006, the archive was invited to salvage anything destined for the skip. They returned with a van full of documents – every piece of paper, from every nook and cranny – that would otherwise have been lost to history.[ref]1. I am grateful to the archivist, Debbie Usher, and the Director of the Middle East Centre, Eugene Rogan, for recounting their trip to retrieve Glubb’s papers.[/ref]

I had the privilege of being the first researcher to sift through this material. It was available to me in the state that it had been salvaged. No catalogue. Just a brief list of what each box might contain. My week at the archive was therefore inadequate to identify relevant documents within this giant haystack.

I had seen enough, though, to realise that this was a treasure-trove of data that could tell a much bigger story. I therefore designed a larger project to explore Glubb’s relationship with two key issues: the origins of the Arab-Israeli conflict and the decline of Britain’s empire in the Middle East.

When I began this new project I had to wait for access to the Glubb collection, while it was re-housed into more appropriate archival storage boxes.

In the meantime I turned my attention to The National Archives where I encountered a paper trail detailing the provenance of Glubb’s papers. This piqued my interest and revealed further evidence of the collection’s precarious existence.

When Glubb was dismissed from Jordan, the king gave him just two hours to leave the country. But Glubb refused to go at such short notice and it was agreed he could leave at 7am the following morning.

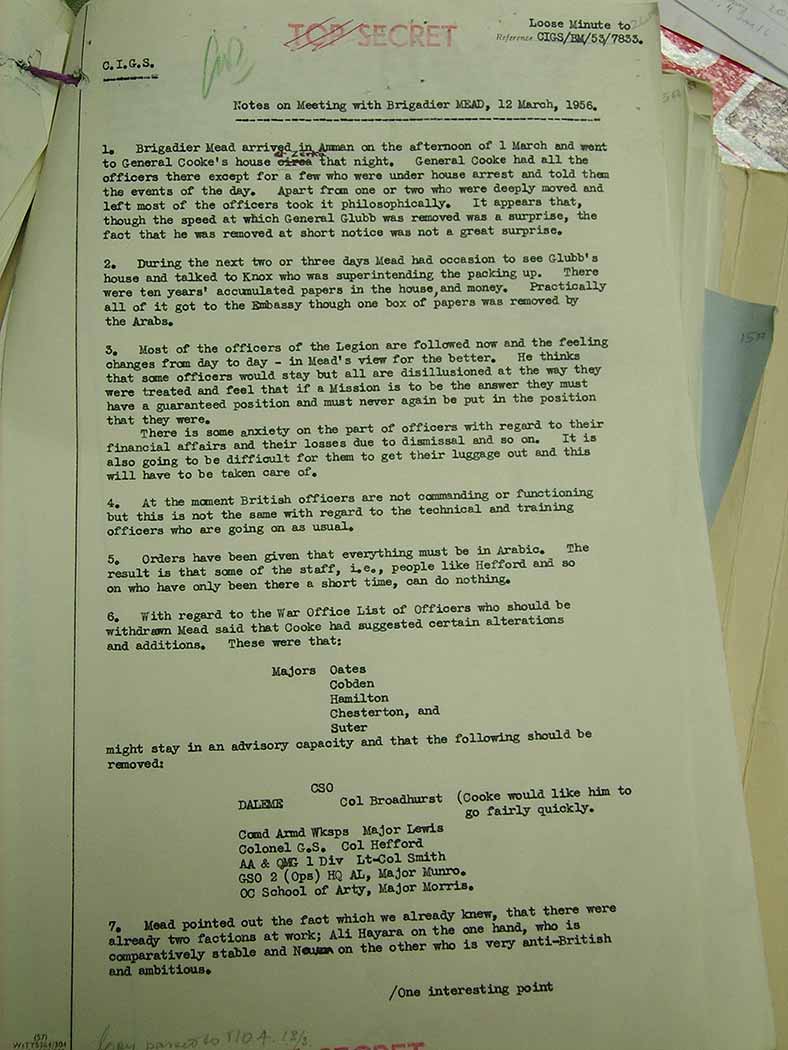

What I discovered at The National Archives was that this brief period of respite proved crucial to the destiny of these documents. Before Glubb departed Jordan, he and the British Ambassador discussed arrangements ‘for the disposal of various secret documents and other material which it would be embarrassing to leave in the possession of Jordanians’. Glubb was instructed to transfer his papers to the British Embassy, from where they would be forwarded to him in Britain, and to destroy any ‘compromising’ documents that he could not salvage.[ref]2. ‘The Dismissal of Glubb’, Duke to Lloyd, 8 March 1956, PREM 11/1419[/ref] The Arab Legion officer who superintended the packing of Glubb’s belongings confirmed that practically all of Glubb’s papers made it to the Embassy, ‘though one box of papers was removed by the Arabs’.[ref]3. ‘Notes on Meeting with Brigadier Mead’, 12 March 1956, WO 216/912[/ref]

Confirmation that Glubb’s papers were despatched to the British Embassy, March 1956 (catalogue reference: WO 216/912)

The Royal Hashemite Archives where this material would have been stored, had it been left in Jordan, are not freely accessible to researchers. Thus, while the possible destruction of some documents is regrettable, the fact that Glubb had time to send his papers to the British Embassy was crucial to their emergence 50 years later – and their accessibility for my research.

The recorded provenance of this collection emphasised its likely significance and enhanced my eagerness to unlock its secrets. Despite being rehoused, it remained uncatalogued. I therefore spent over a year meticulously trawling through each document – every Christmas card, every newspaper cutting. My reward was the discovery of military plans, political correspondence, diary-like notes and a plethora of other pertinent documents, scattered among Glubb’s vast hoard of papers.

In return for this privileged access, I had the pleasure of discarding hundreds of rusty metal paperclips – which posed a threat to the conservation of this material – replacing them with corrosion-free plastic ones. Having reaped the fruits of the documents that had survived Glubb’s dismissal from Jordan in 1956 and the clearance of his family home 50 years later, this was my meagre contribution to their continued preservation. It was the least I could do.

Connecting Collections is a series of blogs by academic researchers, exploring the connections between archives across the UK and around the world.

Hi I found this site by chance. I am interested to know what you wrote as a result of this research. I am his daughter Mary and we cleared the family home after my mothers death.We visited The college on more than one occasion taking up papers and seeing the archives.

Please let me know

Mary Stewart

Hi Mary, I’ve been meaning to get in touch you about sharing my research findings, since my book was officially published a couple of weeks ago. I’ll send you an email in a moment.

Best wishes, Graham

Hello, Graham. As you may know, the Glubb family these days is mostly based in New Zealand, where there are many hundreds of us. We have a Facebook page for the extended family and have added the article about your research with interest. Many thanks and best wishes, Veronica Buckley (granddaughter of Richard Henry Glubb, first Glubb born in New Zealand, in 1879).

Hi Veronica

Thanks for reading and sharing. I’m very pleased to hear that the wider family is taking an interest.

Best wishes, Graham

Graham – my late uncle, Captain George Corfield served with the Arab Legion after WW2. He was awarded the Jordanian Order of Military Gallantry Medal by King Abdullah. I have the medal but we do not know what George did to win this high honour. I wonder if you came across any reference to George during your research in the Glubb papers. Or indeed any information about George. I am very keen to pursue this topic.

I look forward to hearing from you. My son now lives in Oxford so we could perhaps meet some time when I visit him. Kind regards.

Graham, my thesis examined the role of the SSOs as part of the air control scheme in the Middle East. JBG was one of the first and his books were a tremendous aid to the research (lots of AIR 23 papers). In Arabian Adventures, Chap 8, he talks about ‘Rules for Raiders’ and how the raiding was treated as football or cricket. Other authors reference the book, but I’m very interested in looking at the original. Did you happen to find a copy of the Rules as you were examining the papers? If so, might it be possible to purchase a copy of the Rules? Thank you and happy to correspond directly via email if more appropriate.

Dear Graham, I am probably getting sidetracked reading this as this is so interesting, but have a quick question. My Master’s dissertation includes a section on Norman Brook’s supporting role (of Eden, and the whole cabinet) during the Suez crisis. Did you by any chance find any link to Glubb Pasha, or anything he might have done, in relation to Eden’s handling of the crisis?

Hi Mary

Thanks for reading and getting in touch!

(It seems my original attempt to reply failed. Possibly because of the word count. So I’ll try again, splitting the reply into 3 parts.)

My research did touch on the link between Glubb and Suez. The final chapter of my book covers the period after Glubb’s dismissal, including Suez. It actually uses the recently released cabinet secretary’s notebook (written by Brook) to analyse the link between Glubb’s dismissal in March and Eden’s attitude towards Nasser. Hopefully your library has a copy, as you might find that useful/relevant. The focus here is more on the reaction to Glubb’s dismissal rather than Glubb’s direct influence. Eden and Glubb did meet at Chequers after the dismissal, and Glubb’s stance was that Eden should avoid being too hard-line in his reaction to the dismissal – this was more with Jordan/King Hussein in mind, rather than Egypt, though.

Hi Mary

Thanks for reading and getting in touch!

My research did touch on the link between Glubb and Suez. The final chapter of my book covers the period after Glubb’s dismissal, including Suez. It actually uses the recently released cabinet secretary’s notebook (written by Brook) to analyse the link between Glubb’s dismissal in March and Eden’s attitude towards Nasser. Hopefully your library has a copy, as you might find that useful/relevant. The focus here is more on the reaction to Glubb’s dismissal rather than Glubb’s direct influence. Eden and Glubb did meet at Chequers after the dismissal, and Glubb’s stance was that Eden should avoid being too hard-line in his reaction to the dismissal – this was more with Jordan/Hussein in mind, rather than Egypt, though.

Something that I didn’t put in the book, but you might find interesting is that Glubb did write to Eden and Selwyn Lloyd during the summer of 1956, advocating the removal of Nasser. I’m not sure if these letters were read, though. Certainly Glubb had conversations with politicians/Cabinet members such as Minister of Defence Walter Monckton who reported back to Glubb that he put Glubb’s views to the PM. However, I believe Monckton was opposed to Eden’s Suez policy and moved away from the MOD in October, shortly before the Suez conflict actually began.

Something you may also find interesting is Philip Murphy’s chapter in ‘Reassesing Suez”. This examines the debate surrounding the impending publication of Anthony Nutting’s memoirs ‘No end of a lesson: the story of Suez’ in 1967. The opening line of this memoir suggests that Glubb’s dismissal was where the Suez crisis began. It is interesting to note that when Eden was consulted about the publication of this book he asked HMG to send him all the papers relating to Glubb’s dismissal [I can’t remember if this aspect comes out in Murphy’s chapter or whether it is just something that I came across in my own research]. Murphy’s chapter is, if I remember correctly, based primarily on two medium sized files held at TNA, which don’t take long to go through.

An interesting side-note is that Glubb and Eden did communicate in 1967, regarding the Six Day War in June.

I hope that helps.

Best wishes

Graham

Dear Graham, I was interested to come across the reference in your book to my father, Brig. J.C.H.Mead (known as Philip). As a teenager, I was supposed to go to Jordan with my family when he was selected to join the Legion. My father died in 1959. If you know of any photos of his arrival or time in Amman I would appreciate it.

All the best,

Frances Hunter (Mead)

Dear Frances

Thanks for getting in touch. I don’t know of specific photos off the top of my head, but that’s not to say there aren’t any. I haven’t been through the photographs in great detail, and for conservation reasons, there are many photos I’ve not been able to look at yet. One issue with the photographs is that it is not always clear who the individuals are. But perhaps that is something you might be able to help with? I’ll send you a separate email shortly, to see if I can help.

Best wishes

Graham

Hello, Mr. Jevon.

My father, W.J.Bovill, was an Indian Army SSO serving in Mespot throughout the Great War, and will have known Glubb, engaging in some similar activities. He left no papers ! Congratulations on your research on Glubb.

Hello, I am interested in seeing the photos of Bedouins, tribes and the desert taken by Glubb Pasha. Can you tell me about the photos?