8 June is the 70th anniversary (1949) of the publication of George Orwell’s famous novel warning of the dangers of totalitarianism, ‘Nineteen Eighty-Four’. George Orwell is, of course, a celebrated journalist and author, one of the best-known writers in the English language, whose name was even converted into an adjective (‘Orwellian’) to describe a political system in which the government tries to control every aspect of people’s lives. But did you know that Orwell himself was the subject of surveillance by the British state?

This is revealed in a Special Branch file held by The National Archives, a report from which features in our Cold War exhibition. The file shows that Orwell (real name: Eric Arthur Blair) first came to the attention of Special Branch and MI5 in early 1936, when he was ‘on location’, researching ‘The Road to Wigan Pier’, investigating the harsh living conditions among the working class in Lancashire and Yorkshire[ref] Catalogue reference: MEPO 38/69[/ref]. Special Branch concern focused on the fact that Orwell attended Communist Party meetings.

Fear of subversion

Fear of communist revolution, and of Soviet subversion within Britain, ‘an enemy within’, was a major concern of the security services in the inter-war years. This fear can be traced back to the Bolshevik revolution of 1917. Communism was, in theory, an expansionist ideology, to be spread by revolution, and consequently, there was a preoccupation with the ‘red menace’ in the 1920s and 30s.

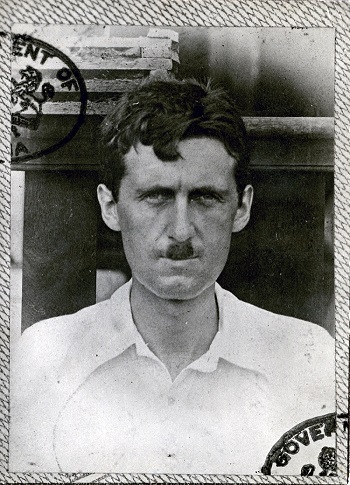

Eric Blair (George Orwell) in 1936, MEPO 38/69

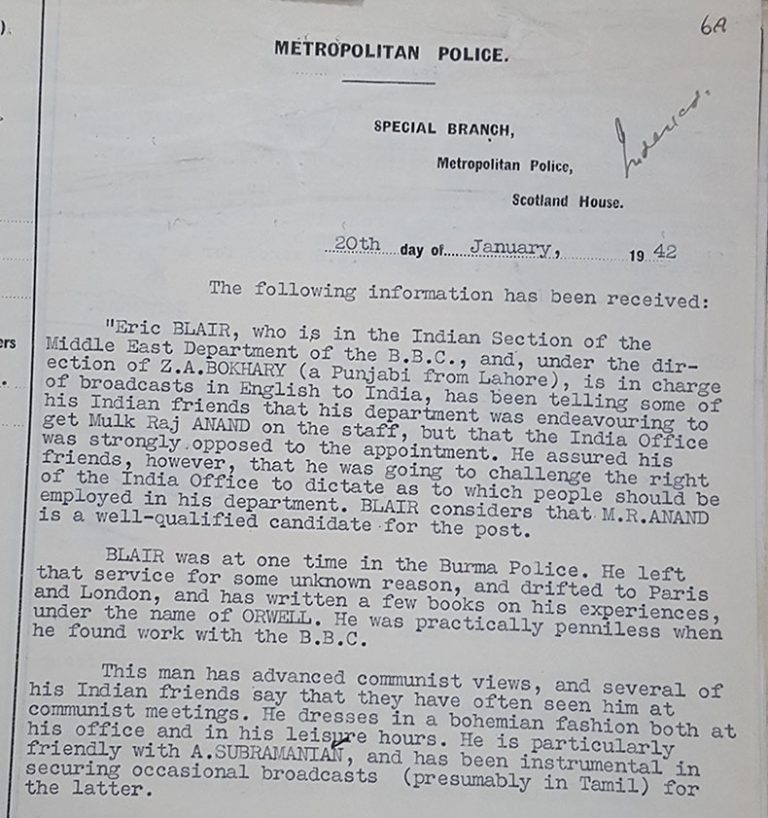

Orwell continued to be a worry for the authorities during the Second World War, as we can see from a Special Branch report by Sergeant Ewing, filed on 20 January 1942. At this time Orwell was working in the Indian section of the Middle East department of the BBC, in charge of broadcasts to India (he delivered some broadcasts in person). An extract from the report reads: ‘this man has advanced communist views, and several of his Indian friends say that they have often seen him at communist meetings. He dresses in a bohemian fashion both in his office and his leisure hours’. To modern eyes this betrays a very ‘sniffy’ attitude about Orwell!

A 1942 Special Branch report on George Orwell, MEPO 38/69

In a note in a Security Service file, it is explained that what Sergeant Ewing meant by Orwell’s ‘advanced communist views’ is that he was an ‘unorthodox communist’[ref] Catalogue reference: KV2/2699[/ref]. Certainly MI5 were aware that Orwell, whilst holding ‘strong left wing views’ was ‘a long way from orthodox communism’. Orwell had developed a loathing of Stalinist communism. This was because of his experiences in the Spanish Civil War, particularly the brutal suppression of the non-Stalinist left in Barcelona in 1937, which he witnessed at first-hand.

A list of ‘crypto-communists’

In the relevant exhibition showcase, another document is positioned alongside the Special Branch report, and the irony which surrounds the combination of these documents is obvious, for it is a list of names of ‘crypto’ (or secret) communists which Orwell gave to the Foreign Office in 1949. To explain the background in greater detail, on 29 March 1949, Celia Kirwan, a friend of Orwell and an employee of the Information Research Department (IRD) of the Foreign Office, went to visit the great author, who was suffering with tuberculosis and was recuperating from a particularly bad bout of illness in the Cotswold Sanatorium in Gloucestershire, located at Cranham. The IRD had been set up by the Labour government to counter Soviet propaganda (which was flooding Eastern Europe). Interestingly, George had proposed to Celia a few years previously, but according to biographers, this had come to nothing; however, they remained friends.

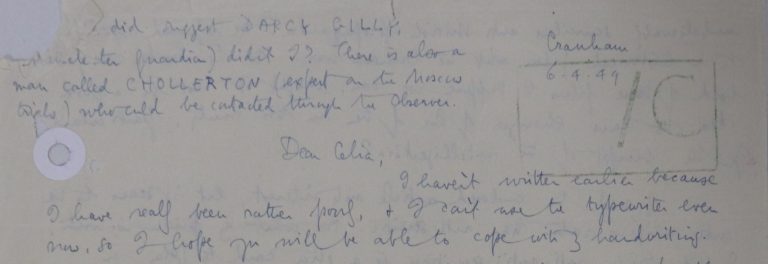

During her visit, Celia discussed aspects of the work of the IRD with Orwell ‘in great confidence, and he was delighted to learn of them, and expressed his wholehearted and enthusiastic approval of our aims’[ref] Catalogue reference: FO 1110/89[/ref]. Orwell suggested the names of writers who might be enlisted to write for the IRD. He followed this up by writing a letter to Celia, dated 6 April 1949, which began:

‘Dear Celia,

I haven’t written earlier because I have really been rather poorly, and I can’t use the typewriter even now, and I hope you will be able to cope with my handwriting’.

Further on he writes: ‘I could also, if it is of value, give you a list of crypto-communists, fellow-travellers or inclined that way and should not be trusted as propagandists’.

Orwell adds that the list should be ‘strictly confidential’, concerned it may be libellous to label someone in this way.

George Orwell’s letter to Celia Kirwan, FO 1110/89

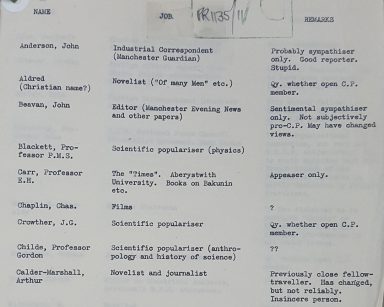

The IRD were delighted by Orwell’s offer and so Celia asked to see the list, promising to ‘treat it with the utmost discretion’. It is unclear whether the list which appears within the file was typed up by the Foreign Office or whether it was provided – ‘ready typed’ – by Orwell or Richard Rees, a close friend who became his literary executor (and who apparently helped Orwell compile the list, according to biographers). It includes some famous names: in the remarks column there are question marks against Charles Chaplin, the comic actor and filmmaker, Michael Redgrave, the actor, and J B Priestley, the novelist and playwright.

Orwell’s list of ‘crypto-communists’ or ‘fellow-travellers’, FO 1110/89

It should be emphasised that no one was hounded or persecuted as a result of this list – it was simply an exchange of information. Orwell believed that Stalinist communism was a threat to Western social democracy and civilisation and felt strongly that this must be guarded against.

Perhaps there were elements of paranoia in Orwell’s outlook, (exacerbated by his experiences in Spain), but it was his sincerely held view that these were people whose loyalties were questionable and he felt it would have been risky to offer them influential positions as propagandists close to government. He had also been highly concerned about the internal threat posed by ‘quislings’, or those with fascist sympathies, in the early part of the war.

Rich ironies are intertwined with these documents, and you can see the Special Branch report and Orwell’s list of names on display in our free Cold War exhibition, Protect and Survive: Britain’s Cold War Revealed, which is open until November 9.

Dear National Archives reception,

I think its important that George Orwell’s integrity in relation to his connection to the British secret services is clarified by the British Archives historical records. I attended the Melbourne May Day Labour rally and march yesterday,Sunday May 7. I was surprised when a communist in the crowd claimed that he believed George Orwell worked for the British secret service which he never ever did.

Eric Arthur Blair opposed tyranny in any form even though he was a Socialist. Communism has been compromised by Stalinism and bureaucracy while capitalism is a failure due to its reliance on free markets motivated only by the tyranny of greed. Some eighty years after WW2, more powerful models of tyranny , written about by George Orwell , in the form of language and media, control us.

How do we know he “never worked for them”? Is this guaranteed to be his *complete* intelligence file?