Content warning: Please be aware that this blog will discuss sensitive and potentially triggering topics including sexual assault.

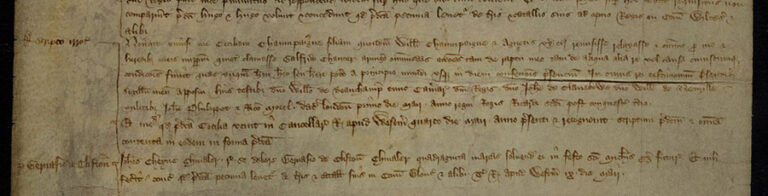

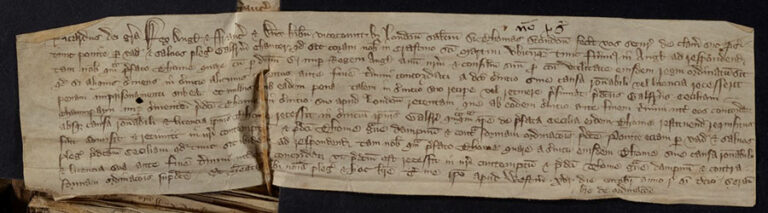

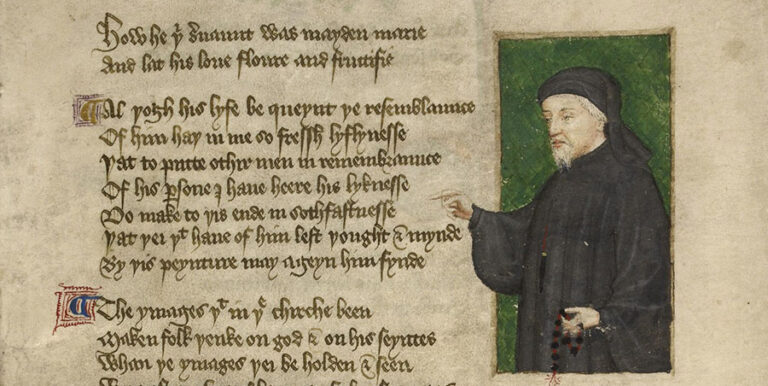

Few medieval records have received as much attention from literary scholars as a group of documents dating from May to July 1380 that involve Geoffrey Chaucer and Cecily Chaumpaigne, the daughter of a London baker. At the heart of this group of records is a quitclaim of May 4, enrolled in the Close Rolls of the English Chancery, releasing Chaucer from ‘all manner of actions related to my raptus’. The word raptus, which in legal contexts can denote ‘rape’, ‘abduction’, and much of the spectrum lying between these terms, has challenged Chaucer scholars ever since Frederick J Furnivall announced this find in 1873.

The matter was given significant new impetus in 1993, when Christopher Cannon discovered a second quitclaim by Chaumpaigne – with the word raptus removed – enrolled in the plea rolls of the Court of King’s Bench a few days after the first. Cannon’s discovery has energised foundational strands of Chaucer studies, in particular feminist scholarship, over the last 30 years, but in this time no new documentary evidence has come to light.

Now, new research into the medieval legal collections at The National Archives has uncovered two new life-records relating to the dispute of 1380 – including evidence of the original legal accusations brought against the poet – which offer a radically different understanding of the documentary evidence. These finds, which clarify the relationship between Chaucer and Chaumpaigne, and the nature of the charges brought in the King’s Bench, have just been published in a special guest-edited volume of Chaucer Review alongside responses from leading Chaucer scholars and historians.

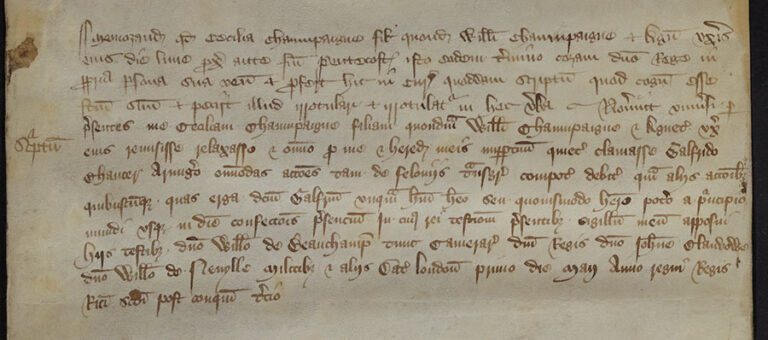

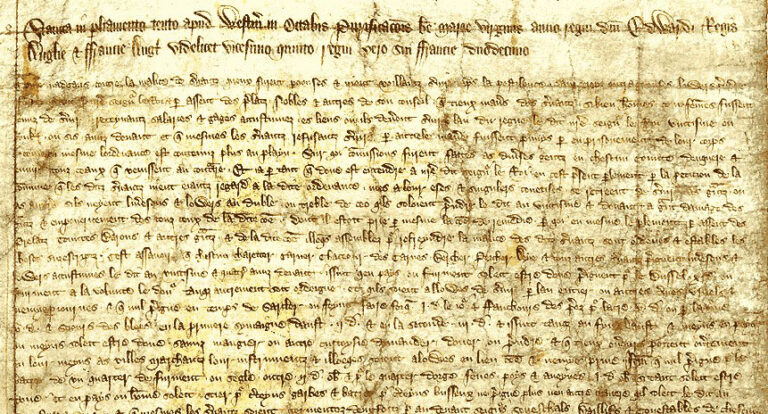

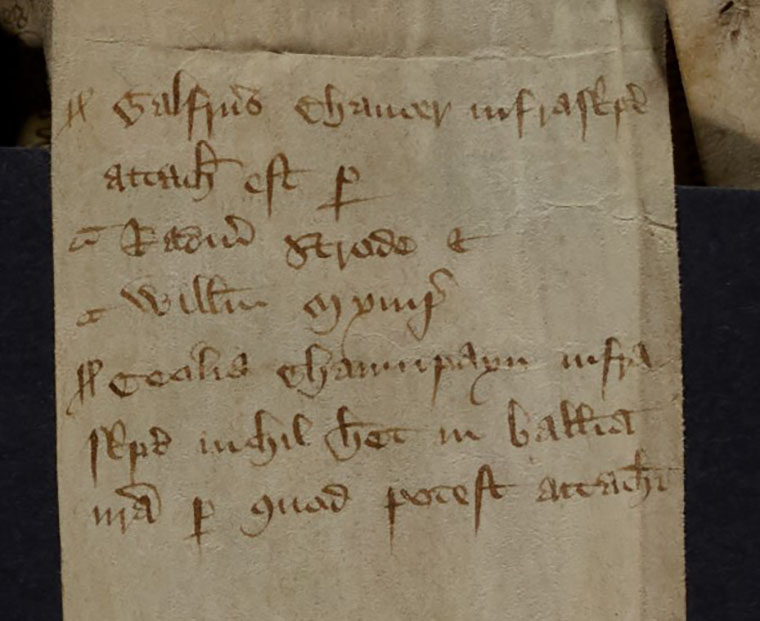

The first of the two newly discovered records is a warrant dated 9 April 1380 (the first day of the Easter law term), in which Cecily Chaumpaigne appointed two attorneys, Edmund Herryng and Stephen Falle, to act on her behalf. They were appointed, not against Chaucer, however, but against a man named Thomas Staundon. Secondly, and perhaps most importantly, they were not appointed to act for Chaumpaigne as a plaintiff in the case brought before the court, but as a defendant, against charges brought under the Statute and Ordinance of Labourers (1349/51) (see footnote 1).

According to the warrant, it was alleged that Chaumpaigne had been employed in Staundon’s service, but had left without license before the end of the agreed terms of that service. Staundon’s name may be familiar to those working with Chaucer’s life-records, even if the nature of the two men’s interactions has remained obscure to date.

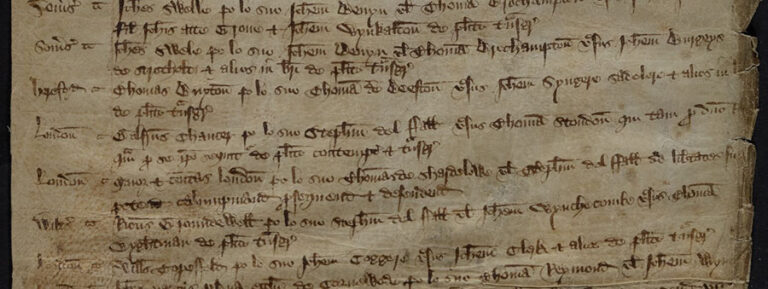

In Michaelmas term 1379 (two terms before Chaumpaigne would appoint her attorneys), Chaucer also appointed the attorney Stephen (del) Falle to answer charges brought against him by Thomas Staundon, described in the entry as ‘trespass and contempt’, although no further proceedings were recorded in the plea rolls (footnote 2).

That Chaumpaigne and Chaucer were both recorded as appointing attorneys in the King’s Bench against Staundon in the months between Michaelmas term 1379 and Easter 1380, one of whom (Falle) acted on behalf of both parties, was the first indication that the established narrative regarding the Chaumpaigne quitclaim required re-consideration, as did the nature of the accusations being made.

It also changed the known timeframe of events. If the two cases were connected – and it seemed likely that they were – then in order to work out what might have happened, we had to look at the records from late 1379 rather than the first months of 1380 for any evidence of the original charges brought in King’s Bench.

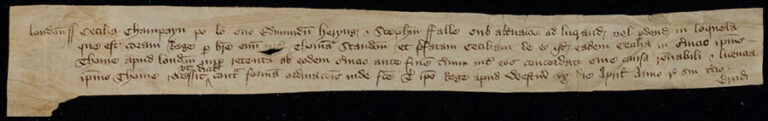

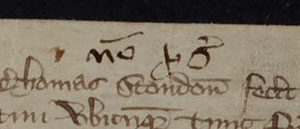

Upon consulting the relevant files, we were able to locate the original writ, dated 16 October 1379, which brought an action by Thomas Staundon, against both Geoffrey Chaucer and Cecily Chaumpaigne under the Statute of Labourers.

The Statute and related Ordinance were enacted in response to the economic difficulties that emerged after the first outbreaks of the plague in England in 1348, and were designed to provide new labour regulations in a restricted labour market, to combat rising wages, and to prevent the poaching of servants from employment on the promise of more generous terms.

It is upon the latter clause that Staundon’s action was founded. He claimed that:

‘the aforesaid Geoffrey admitted and retained Cecily Champayn, formerly the servant of the aforesaid Thomas, in his service at London, who has departed from the same service before the end of the agreed term, without reasonable cause or licence of Thomas himself, into the service of the said Geoffrey’

Furthermore, ‘although he himself [Chaucer] had been requested to restore the aforesaid Cecily to the same Thomas’ he had not done so, to Staundon’s ‘grievous loss’.

So how can we reconcile these new findings with the language of raptus as recorded in the Chaumpaigne-Chaucer quitclaim? Our new findings suggest that the legal release may have been intended to counter a charge of procurement (essentially the act of poaching someone else’s servant, possibly for better wages).

Having established that the context for the close roll release was not an action brought by Chaumpaigne against Chaucer, but rather an action brought by Staundon against both Chaumpaigne and Chaucer, a radically different reading of raptus becomes possible. The 1380 quitclaim can in fact be seen as a convenient means of countering certain actions (or potential further actions) that might have been brought by Staundon.

Had Chaumpaigne been physically abducted out of Staundon’s service by Chaucer, there was a clear legal route for Staundon to take. Commonly in such cases, the first master would take an action against their former servant under the Statute of Labourers, and a simultaneous action of trespass against the abductor. No evidence of any trespass actions against Chaucer can be found in the files, and so while we can’t rule out the possibility, if Staundon thought a physical abduction had taken place, for some reason he chose not to pursue this course of action.

Procurement, however, was much more of a legal grey area. Contemporary legal debates suggest that the royal justices were not in agreement about whether the poaching of servants could be prosecuted as trespass (for the taking of the servant) or solely under the Statute of Labourers (for retaining them). The matter would not be resolved conclusively until the 15th century. Pursuing such a prosecution under the Statute of Labourers was therefore the safer course of action for Staundon, as the employment of a departed servant (who had left without permission), was in itself illegal, but the possibility of a second action of trespass for the procurement remained.

If we read raptus as representing the physical act of Chaumpaigne leaving Staundon’s service – using the language of ‘abduction’ to represent a physical transfer from one household to another – we can see the quitclaim in a new light. By stating that Chaucer is released from all actions, or future actions, relating to her departure, the quitclaim freed Chaucer from any involvement with Chaumpaigne’s departure from Staundon’s service, and effectively acts as a statement that she left of her own accord (or through the involvement of others).

At a stroke, the quitclaim removed any means for Staundon to pursue allegations of procurement against Chaucer, as he could now no longer be linked to Chaumpaigne’s departure from service, only accused of retaining her after she had departed.

The remaining charges under the Statute were relatively simple for both Chaucer and Chaumpaigne to defend. Agreements for service at this time were not based on formal written contracts, and the terms of such service could be argued or simply denied. Issue could often be taken on mere questions of fact – permission to depart, difference of dates of contract, lack of payment, denial of retention or of departure – several of which could potentially have been argued by Chaucer and Chaumpaigne.

At an unknown date in Easter 1380, Staundon withdrew his action. A later addition at the top of the original writ states that it was ‘non prosecutum’ (not prosecuted), indicating that Staundon had ceased to pursue Chaucer and Chaumpaigne.

It is, of course, impossible to rule out an act of physical or sexual violence in the events that took place around Chaumpaigne’s move from Staundon’s service to Chaucer’s, or the possibility that she was coerced into agreeing to a release against her will. However, the new evidence presented in our article indicates that the specific legal accusations brought against Chaucer in 1379-80 in the court of King’s Bench were not charges of rape, and they probably did not refer to a physical abduction (or at least there is no evidence for this among the court’s records), but rather related to a labour dispute. Certainly it is clear from the newly discovered evidence that the release was produced in response to an accusation made by Staundon against the co-defendants, not by Chaumpaigne against Chaucer.

These finds, which clarify the relationship between Chaucer and Chaumpaigne, and the nature of the charges brought in the King’s Bench, have recently been published in a special edition of the journal Chaucer Review alongside responses from three leading Chaucer scholars, a new biography of Chaumpaigne and an article on the importance of understudied legal collections for medieval literature and historical studies. You can read the open access research here.

It has often been assumed that there is little more to be found by those searching for life-records of Chaucer and his associates. These new finds, however, demonstrate the exciting potential for new life-records, Chaucer or otherwise, to come to light among the relatively unexplored masses of legal records at The National Archives.

Footnotes

- The Ordinance of Labourers (1349) and the Statute of Labourers (1351) are here taken together as connected pieces of legislation. The statute of 1351 supplemented the ordinance of 1349, in which year Parliament was unable to meet due to the Black Death.

- The attorney is named as both ‘Stephen Falle’ and ‘Stephen del Falle’ throughout the entries. He was a filacer of the court (one of the clerks charged with writing, filing, and enrolling the writs), who regularly acted as an attorney in the same court.

Sebastian Sobecki is Professor of Later Medieval English Literature, University of Toronto.

Please could you tell me which biography of Chaucer you would recommend. My data are on Wikipedia: Robert Edward Gurney

Marion Turner’s Chaucer: A European Life.