Iron gall ink was first mentioned by Pliny the Elder in AD23 and was the most common black (and sometimes brown) ink for writing and drawing in Europe from the 5th to the 19th century, and although often associated in most people’s minds with manuscripts written by monks in medieval monasteries, it was even used in the 20th century.

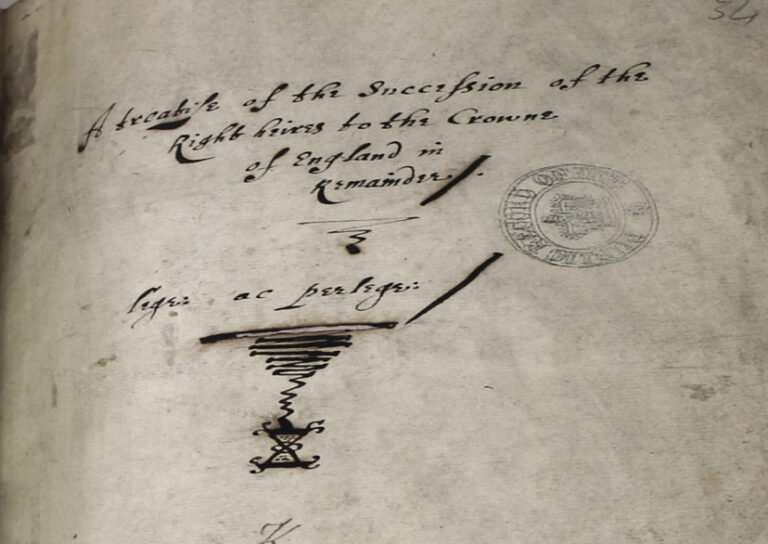

The main ingredients in iron gall ink are oak galls, produced by an oak tree’s reaction to wasps that lay their eggs inside the bark of the tree, and iron (II) sulphate. Unfortunately for institutions involved in the long-term preservation of documents, manuscripts and artworks, such as The National Archives, these ingredients make iron gall ink inherently unstable. It fades and corrodes over time, weakening areas where applied, and can eventually cause discoloration, brittleness, cracks and holes, especially in paper. To make matters worse, humidity causes the iron ions in the ink to move further through the paper, resulting in even more degradation. Ultimately this leads to a loss of legibility and the physical integrity of an object and in extreme cases, may result in a document resembling lace instead of paper!

What does The National Archives do about this?

The National Archives is home to millions of historical paper and parchment documents, stored on over 185 kilometres of shelving which date from the 11th century to the present day. So we have a lot of iron gall ink lurking in our collection!

Some of the most famous examples of documents in The National Archives collection written in iron gall ink include the Domesday Book, Shakespeare’s Will and the confession of Guy Fawkes.

To preserve the collection and to slow down the rate of iron gall ink deterioration, we keep the records in a controlled and stable environment within a temperature range of 13 to 20 degrees Centigrade and a relative humidity range of 35-60%.

If a document contains very corroded and fragile iron gall ink, then usage may be restricted to staff in the Collection Care department who can handle these documents for users. Careful handling can prevent bending and flexing which may crack the ink, leading to tears and losses. The readability of faded iron gall ink can also be enhanced for users by using a multi-spectral imaging system to extract information not visible to the human eye.

In some cases, conservation treatment of a document with iron gall ink may be required, for example if the document is requested for an external exhibition or to prevent loss of the text. As humidity catalyses the chemical reactions that cause the ink to degrade, ‘dry’ treatments that use minimal water are used. Treatments will often include the use of solvent-based adhesives in alcohol or gelatine for repairs as this can bind a certain amount of soluble iron (II) ions, inhibiting corrosion. Japanese tissue paper is also used to support or infill weak or lost areas, as seen in the image below.

A very interesting blog, so nice to read about the technicalities of document preservation. Thank you so much.

As a former stationer I have sold hundreds of bottles of iron gall blue-black ink, described as ‘permanent’. Perhaps I should apologise!

The need for an ink to complete the new registers for births, marriages and deaths introduced in the 1830s lead to the development of a replacement black ink. Henry Stephens, the erstwhile room mate of John Keats, developed a new permanent black ink and founded Stephens’ Ink.

Would love to know more detail of the conservation treatment.

Is there a difference between the deterioration of gall ink on parchment or vellum documents?

Also, how are you very old documents stored; flat, rolled or folded.. as appears to have been the popular method with solicitors. Cheers.

Once prepared, how was ink stored and how long did it last in the 17th and 18th centuries? Did it have to be rehydrated for intermittent use in, for example, parish registers?

Great that these extremely important documents are preserved.

Love your blogs as Librarian in Australia

I have worked with many 16th century documents written with iron gall ink on hand laid paper. I have found that those papers least consulted have held up best, some sheaves that were bound in the late 18th and early 19th centuries in almost pristine condition. Perhaps the lack of exposure to atmospheric gasses and moisture is the key to better preservation, in which case I am glad I have poked around in obscure corners of the archives!

Is the multi-spectral imaging system you mention available to public users of TNA? You have ultra-violet lamps of course, but a multi-spectral imaging system sounds even better.

I once consulted a large vellum roll of 50 membranes dated 1294 in the reading room (E 179/120/3). The ink was as black and clear as though it had been written yesterday. I only looked at a few membranes but I don’t remember noticing any fading, corrosion, discoloration, brittleness, cracks, etc. Perhaps it wasn’t written with iron gall ink? Was soot or charcoal an ingredient of ink in those days?

Is Stephens’ Ink the most long-lasting ink you can get nowadays? Of course, it’s no good using high quality ink on poor quality paper. Vellum is very expensive. What paper and ink do the archivists recommend to ensure long-term preservation of one’s records?

Kosher Gall ink from oak trees was used by Jewish scribes a 100 years ago to write with quills on parchment skin to produce Torah scrolls.

I would be interested to see the replies to Adrian Brockett’s questions especially the use of multispectral imaging – particlularly for chancery court papers. An infra red light source might help – are these sources available to use at TNA and how does one operate such a system?

Could you please advise on laminating old documents? Is that a good way to preserve them?

I have seen the use of plastic slip covers in other archives, but laminating has proved problematic in the past. Current archival best practice is not to do anything that will permanently alter a document, and having to remove lamination later could certainly do that. I am not sure that under current practices the binding into volumes that many of the 16th century state papers (the field I am most familiar with at TNA) underwent in the late 18th and early 19th centuries would be done today.

@Adrian Brockett:

I am not a professional conservator, but I AM a BFA Studio Art/BA Costume Design who does a lot of research into archival practices etc to protect costumes and artwork for the future.

The first thing you want to do is find archival-quality paper, specificially sold as such, made to those standards. A lot of artists’ papers are archival because of the issue of posterity/museum display.

Inks used should also be archival quality.

When the document is finished, store in an acid-free paper envelope to allow it to breathe but protect it from UV light, which can fade some inks, in a cool, dark place. Plastic boxes and envelopes can trap humidity in more humid climes, and the moisture can cause mildew and deterioration of the paper being stored.

Please explain the difference between iron gall and oak gall inks.

Are they the same?