In October 1917 Russia withdrew from the First World War. One consequence of this withdrawal that you may not be aware of is that Russian nationals living in Britain suddenly became eligible to serve in the British Army.

Throughout 1915 there had been what was referred to as the ‘Conscription Crisis’. Too few men were enlisting in the forces to meet the needs of the industrial, mechanical nature of the First World War. In January of 1916 conscription was brought into force to meet the demand for men.

On 14 April 1916 the Home Secretary, Herbert Samuel, sought an amendment to Section 95 of the Army Act which imposed limitations on the enlistment of foreigners into the Army. He was hoping to encourage more aliens to join the British forces, or at least the territorial force. It was decided that foreign nationals who wished to join the British forces could do so as long as no more than 2% of the fighting force was made up of aliens. [ref] 1. For a discussion about the enlistment of aliens into the British Army see file WO 32/4773. [/ref]

The exception to this rule related to nationals of Allied countries. There was an agreement in place that all French, Belgian and Russian subjects living in the UK who desired to fight in the War should be compelled to return to their own country to join their respective armies. Since Russia was no longer a belligerent after October 1917 the government felt that this agreement no longer applied. Mr Samuel especially considered it unfair that Russian shopkeepers should remain exempt from service, profiting from the absence of British shopkeepers who were serving in the Army.

At this time, aliens living in the UK already had to register their personal details with the police as a consequence of the 1914 Aliens Registration Act, a process which was threatening to overwhelm the resources of an already stretched police force. It was decided that any alien who enlisted to serve in the forces and who ‘render good service in the British Army’ would be excused from paying the fee for naturalisation, effectively ‘fast tracking’ their application for naturalisation and offering an incentive to those thinking of joining up.

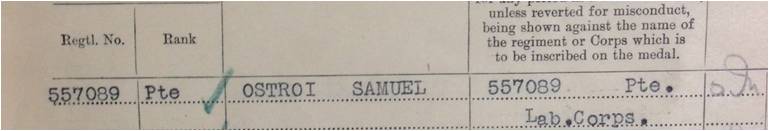

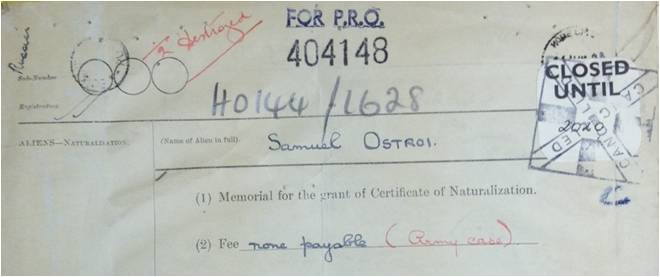

Where this information becomes useful is that each of these military men who became naturalised has a case file here at The National Archives. These case files (in record series HO 144, searchable by name via Discovery, our catalogue) will give you detail of their individual service. An example is Samuel Ostroi (whose medal roll entry is above) [ref] 2. WO 329/1890. [/ref].

He has no service record surviving[ref] 3. if this survived, it would be available to download for a fee from Ancestry, or view for free at The National Archives, Kew. Please note, this section was amended after publication to clarify where and how records could be accessed.[/ref], however his naturalisation case file tells us his regiment, 8th Battalion, Labour Corps, and dates of service, 18 April 1918 until a medical discharge on 19 November 1919. [ref] 4. HO 144/1628/404148. [/ref]

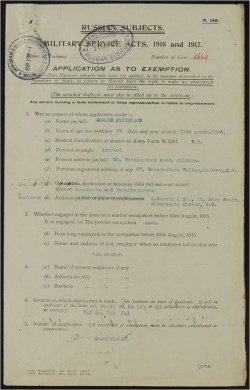

Of course, as much as Russian nationals were obliged to serve under the Military Service Act, they were equally entitled to appeal their conscription. The records of the Middlesex Appeals tribunal in record series MH 47 contain a great many records of Russian subjects who had either refused to return to Russia therefore forfeiting any right to protection from conscription or those who had commercial, familial or business obligations which would necessitate an exemption from service. We are currently digitising these files ready for release on our website later this year. The case papers provide a great deal of information about these men, their businesses and their families.

An example of a Russian attempting to gain an exemption is Adolphe Feitelson from Kovna (Kaunas, Lithuania) who was claiming exemption on business grounds, ill health and that he was supporting a wife and young child, his mother and two sisters. [ref] 5. You will find Mr Feitelson in MH 47/45, case number M4693. [/ref]

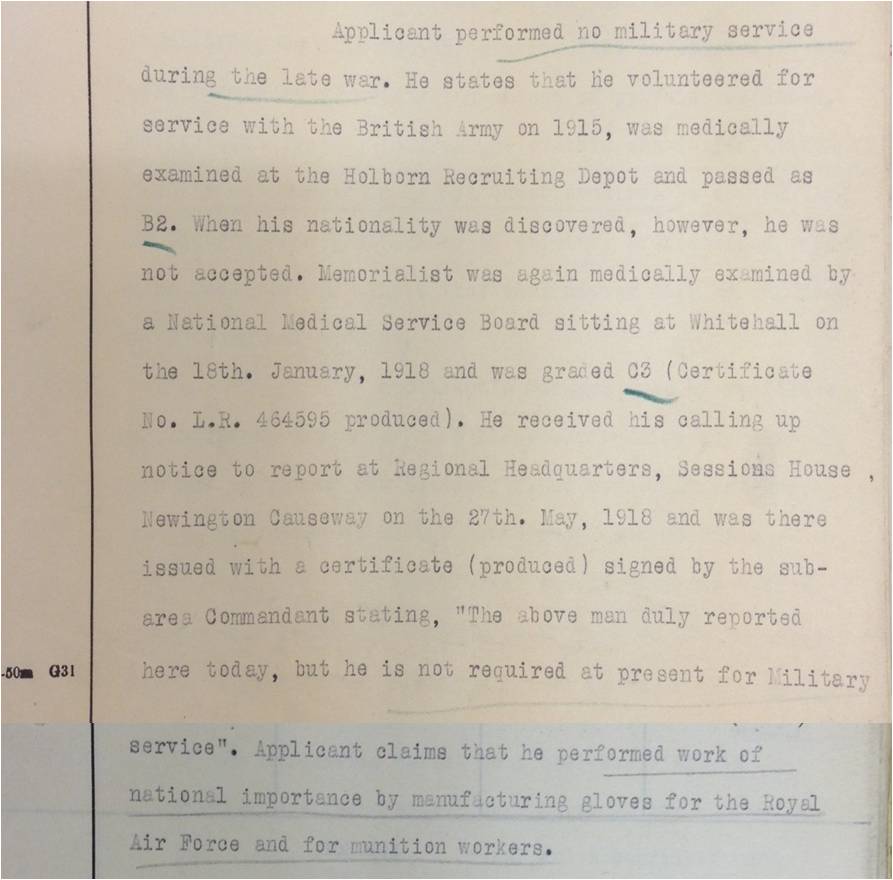

His application was refused and Adolphe was only granted a temporary exemption until 28 February 1918. Looking online, again there is no indication of service – not even a medal record in this instance. In an effort to discover whether or not Adolphe saw any service we can examine his naturalisation case file for details. [ref] 6. HO 144/5500. [/ref]

This file explains that Adolphe presented himself for service but was not required. Instead, he saw out his time undertaking work of national importance manufacturing gloves to be used by members of the Air Force and workers in the munitions industry.

Other examples of Russian men who appealed conscription and who also have naturalisation records include Richard Raphael, [ref] 7. MH 47/60, case paper number M5218 and HO 144/1325/254643. [/ref] a tobacconist who, we learn from his case file, also saw out the war undertaking work of national importance with Waring & Gillow assembling aircraft. A further example is Woolf Okin who claimed, as a boot maker, to be in a reserved occupation [ref] 8. MH 47/60, M5273. [/ref]. Mr Okin also suffered from ill health and had four children which resulted in receiving a rolling temporary exemption, the last of which was due to expire on 27 December 1918. [ref] 9. The naturalisation case file of Mr Okin can be found at HO 144/10959. [/ref]

I would point out that Ancestry do not have files but they are copies of what The National Archives keep as a public record, so that if the file did not survive at the War Office then Ancestry or any other company do not have the records. This is an issue (claiming files as their files) that seems to be increasing and it is disappointing that TNA appear to be referring to the files as Ancestry’s.

The HO 144 files may be on the catalogue/Discovery but a number are still closed and researchers may need to make an Freedom of Information Act request to see them

The situation on employment of Aliens was very much different during the Second World War where the Home Office in most cases did not accept requests for British Nationality.

I thoroughly with David Matthew when he writes “it is disappointing that TNA appear to be referring to the files as Ancestry’s”

I fact I would go further and say that the whole exercise of “privatizing”r records that belong to the nation will forever mark a particularly venial development at the archives. It was no doubt driven by the same gang of scoundrels who gave us the Credit Crisis. It will undoubtedly be subject to legal challenge in due course and just as soon as the interest in the records grows to critical mass.

Words do not exist to express just how much I despise the whole gang of parvenus and charlatans that visited us with this “improvement”.

Dear David and Denis,

As the blog post states above, the available case files can be found at The National Archives and are searchable via Discovery, our catalogue.

With reference to Ancestry, The National Archives offers opportunities for businesses to work with us in widening online access to the records we hold.

These co-branded arrangements – for digitising records and making them available online – are called Licensed Internet Associateships. Any business satisfying the qualifying criteria (which are published on our website) is welcome to compete for a Licensed Internet Associateship. We will evaluate any proposals for digitising particular series of records to determine who best meets all the published major requirements of a Licensed Internet Associateship agreement.

Associates like Ancestry.co.uk are providing a value added service making our records easily searchable and more widely available to our readers in their own homes worldwide.

The Associate is required to fund investment in digitisation, cataloguing, indexing, hosting, delivery, technical support and marketing of Online Services of National Archives-held records. The National Archives does not pay for any part of the development of the service, but receives a royalty based on a percentage of net invoiced revenue from the Online Service. This is retained by the Archives and used to fund other projects.

There is no question whatsoever of these records being privatised, indeed we must stress that as part of the co-branding arrangements with Ancestry.co.uk a number of datasets of National Archives-held records can be accessed in our reading rooms at Kew where the charges have been waived.

The costs involved in implementing and maintaining online services are not inconsequential and this approach fits in with our e-Business Strategy, in response to the government’s target to enable citizens to have electronic access to government services. Online access to digitised images of our documents over the internet is a very important element of this commitment.

The reality is that digitising these documents and making them available on the Internet has always been a task beyond the resources of The National Archives because of the vast size of the archive. We therefore sought commercial partners to help us achieve this vision by participating in the commercial digitisation of genealogical and other records.

Dear Ruth,

Thank you for the detailed reply and the reasons why TNA outsource the work, which is understandable.

I would refer to the comment by TNA that “He has no service record surviving on Ancestry” (why not just say that no record exists or survives at TNA?) and the information on his service comes from his British Naturalisation record which indeed is at TNA. The fact is that Ancestry claim the records as their own, you only have to look at the First World War Army service records where there are more than one version of varying lengths and the almost total mis-transcription of the 1911 Census, thankfully Find My Past got it done correctly. It is not any good if researchers can’t find the information because of mis-transcription or no transcription at all. There was also the “UK” Divorce records whereas Scotland and Ireland not only have different legal systems but also hold the records in their own national archive and not at TNA . It does seem TNA have little or no control on Licensed Internet Associateships.

David Matthew,

I am a U.S. citizen and resident. I arrived here because of the National Archives UK Lab’s excellent DROID file format ID program, and ambitious, worthwhile PRONOM project for digital preservation of well, nearly everything worthwhile!

I’ll get to the point. I blanched at the very same sentence that you and the other gentleman noticed, namely, that

“he had no record surviving on Ancestry [UK’s repository]”.

I use Ancestry for referencing U.S. and (some) Eastern European historical documents. The original source is ALWAYS the governmental archive, or state library, or church record or ship’s log etc. Ancestry does digital scans of the original documents, or obtains copies of digital scans of the original documents. Usually, the scans of the originals are available on the Ancestry website, which minimizes the adverse effects of transcription errors. Transcription errors are all too common! I consider it vital to verify everything with a scan of the original document, or ideally, the physical version of the document. The latter isn’t always extant, even with the U.S. government.

In the past, Ancestry was exceptionally good about providing comprehensive access to most information, gratis. Part of that was due to, well, other factors, for those who wished to trace their genealogy. Recently, Ancestry seems to have become much more restrictive. I suspect that the economic crisis in the EU and USA is taking its toll.

I understand the National Archive UK’s need to defray some costs of digitization. I think the word choice was VERY unfortunate though. My impression is that the Nat’l Archive UK is, in fact, scrupulous about citation standards. This

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/records/citing-documents.htm indicates, to me, that original sources and responsible document citation practices are observed.

Yet… I wish that I were able to obtain historical documents directly through my own National Archives of the U.S., without an intermediary. It is possible, but not feasible. I have little choice besides Ancestry, who was and may still be the best of such historical document and data “middlemen”.

Thank you for your comments. We have now clarified the wording in the sentence and added a note to mark the amendment.

There was an agreement in place that all French, Belgian and Russian subjects living in the UK who desired to fight in the War should be compelled to return to their own country to join their respective armies.

Not only those countries, but Italy too,details in HO 45/10783/28147, and the USA, HO 45/10882/344662.

The Italian agreement, at least, appears to have been a bi-lateral one, with British men in Italy also required to return to the UK or be subject to the conscription laws of Italy.

Some years ago I was involved with the Anglo-Italian Family History Society in transcribing the details of all the Italian men recorded in the former piece which the Society subsequently published. The Italian Embassy estimated that there would be more than 3200 men eligible for repatriation, a wild overestimate as only 950 eventually returned, it is not clear what happened to the rest. For example it was estimated that some 200 men would leave Liverpool, in the event the police there reported that “the Consul … did not think there would be more than five men leaving here…At 2.a.m., on the 9th inst., one Italian, Vincenzo Falcone, 28 Stafford Street, Liverpool, presented himself at Lime Street Railway Station, and he was the only man to entrain for London.”

The authorities seemed rather disappointed with the occupations of some of the men (shades of the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy):

236 Confectioners; 57 Cooks; 87 Waiters; 56 Hairdressers; 74 Ice cream sellers; 47 Shop assistants.

Can anyone please advise whether South Africans were regarded as “aliens” at the time (although I doubt this) and are there perhaps any records of South Africans enlisted in the various forces.

Many thanks

Renee

I bought a mostly derelict old house in the mid 90’s in Tillingham, Essex and amongst the accumulated rubbish I found an old shell case that had been engraved with the following;

“A souvenir from Vimy Ridge, 1918. Private S. Ostroi, 557089, Labour Corps.” I still have it.

I can send you a pic if you’d like.