As a state archive, The National Archives holds many items relating to the experiences of migration and citizenship. These records intersect in a surprising way with past sex worker stories, amounting to a rich collection of records about potential sex workers seeking to work in the UK.[ref]Although the records are rich, tracing specific individuals is difficult.[/ref]

The sex worker from abroad was an alluring prospect, and they often played up to this with exotic sounding names – such as French Fifi, who emphasised her French nationality. However, there was also an extra level of scrutiny on individuals migrating to the UK for sex work; evidence of ‘immoral’ behaviours or illegal activity could be used to deport migrant workers. A snapshot from Home Office records in 1922 shows women from France, Lithuania, Russia, Belgium and Poland all being observed because of their engagement in sex work[ref]’Traffic in women and children, 1922-1924′. Catalogue ref: HO 45/11607.[/ref]. The subsequent charges ranged from loitering for the purpose of ‘prostitution,’ ‘soliciting,’ being a ‘disorderly prostitute’ and failure to register on arrival. All except one were deported. Ultimately an uncertain migration status made, and still does make, sex workers more vulnerable to the law.

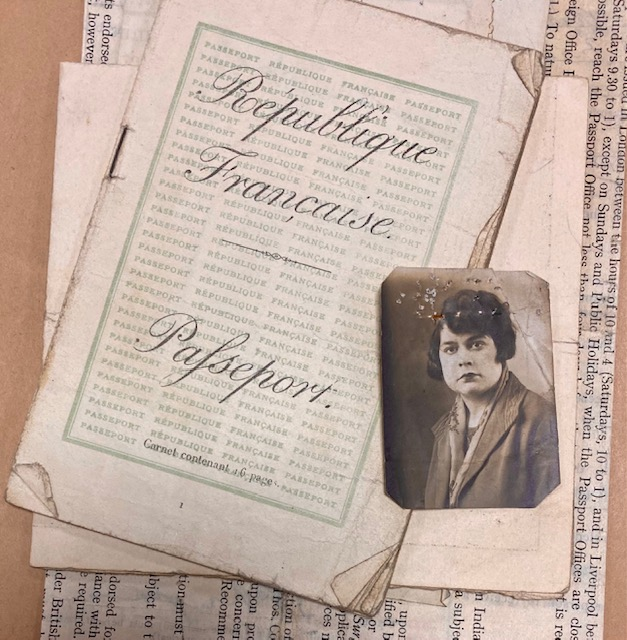

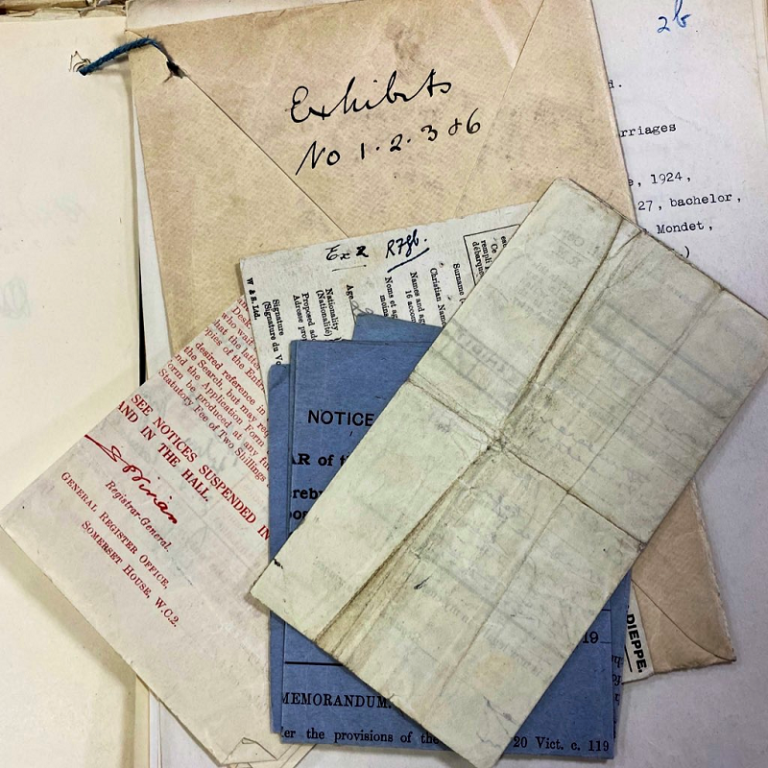

In some ways this actually means we have more details about these sex workers than about those who did not travel from abroad, because of the extra level of interest in their lives and movements. These sex workers were often looked out for at borders, had passport details gathered and marriage certificates examined if a ‘marriage of convenience’ (a marriage for purposes other than love or commitment) was suspected.

These women were also vulnerable to being trafficked into the country against their will, as multiple records show[ref]This can be seen in the catalogue searches under terms such as ‘trafficking’ and under the archaic term ‘white slave trade’.[/ref]. The lack of explicit sex workers’ voices in these records means it is often very hard to differentiate between those who migrated by choice and those who were forcefully trafficked, although the majority seem to have chosen this fate. This lack of clarity presents a particular challenge in using these records. The language can be particularly problematic in such records as well, with words such as ‘alien’[ref]’Aliens’ was the legal terminology of the time for immigrants coming to Britain.[/ref], ‘undesirable’ and ‘expulsion’ regularly used, reflecting attitudes and the legal language around immigration at the time.

London, in particular, was a central hub for those people selling sex (although towns, ports and barracks all over the country also saw the presence of sex workers in significant numbers). Sex workers in the metropolis had always represented the richness of London’s diversity; some of this came from permanent residents, and some from transitional migration into the city. By 1936, a Metropolitan Police report on the West End claimed that in C Division alone they knew of 116 foreign women working as sex workers who had married British men. In response, police developed an ‘album of foreign prostitutes and their associates’. The album does not survive in our collections but associated correspondence detailing its purpose, restricted distribution and a blank entry sheet does [MEPO 3/ 988].

Marriage of convenience

In the 1920s and 30s there are a surprising number of cases which reference women attempting to come to England on the basis of their marriage to a British subject. When looked into by the authorities, some appear to be marriages of convenience, in this case essentially a cover for women doing sex work[ref]These cases talk explicitly about women. I have not come across similar cases relating to men or non-binary individuals.[/ref]. By marrying a British subject they were aiming to avoid restrictions under the Alien Restrictions Order.

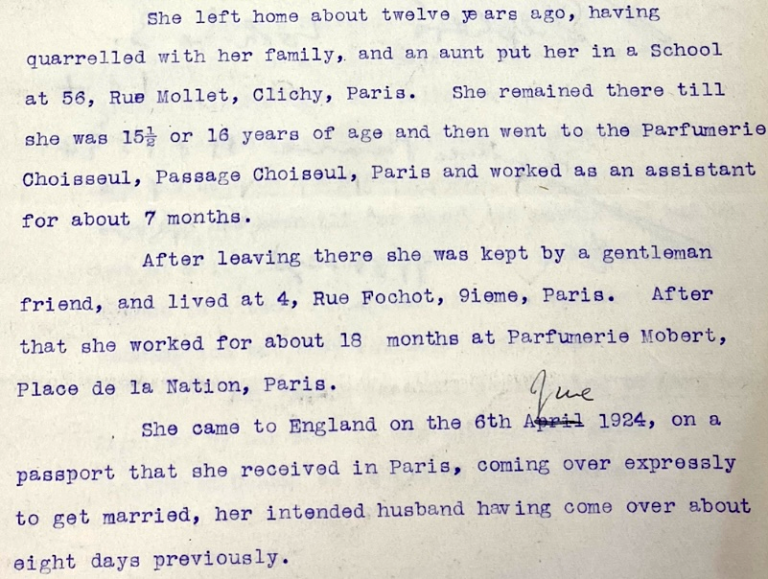

A particular case from 1924 illustrates the complexity of such marriages of convenience. Germaine was born in 1900 in Port Villez, France and was 24 years of age when she came to London to marry[ref]This post intentionally uses Germaine’s first name only.[/ref]. A detailed history of Germaine recounts how she met her husband when he was working as a butcher in France; they lived together for six months in Paris and then married at St Pancras Registry Office on 13 June 1924. Her husband was described as ‘tall, thin, pale and clean shaven’, while Germaine was described as ‘5 foot 4, pale complexion, hair fair, eyes grey, medium build and smartly dressed’. After their marriage, he rented a property for them and then disappeared without warning for months, supposedly selling cattle in America.

The Metropolitan police believed this was a marriage of convenience, designed to get Germaine in to the country to then solicit as a sex worker. Her identity was noted to be identical to a woman of the same name, who had twice been convicted at Marlborough Street Police Court in 1924 and 1925 of soliciting in the West End. The files note that this case followed a standard pattern of husbands disappearing after marriage, ‘in all these cases the men have left the women almost in the steps of the Register Office’. Contrary to Germaine’s own statement, police identified that on entering the country she claimed to be travelling for business and listed her profession as a dealer. While on her marriage certificate she was listed as a furrier’s assistant (a person who prepares or deals in furs). This could have accounted for her saying she was a dealer, although officials saw this all as more contradictions in her story. Germaine herself eventually admitted her husband sent her no money so she turned to soliciting on the streets.

Investigations determined that Germaine had been a sex worker for many months, often working on the streets with another French woman, who had been bigamously married to a man who was already married to multiple women to come in to the country. Police observed that the whole time she had been in England, Germaine lived in flats known to be occupied by sex workers. It was suggested that her fingerprints and photos should be sent to police in France to make them aware of her line of work. For these offences relating to selling sex, Germaine was fined. However, the potential charges of being an ‘unregistered alien’, making a false statement to the immigration officer and making a false statement to the police were considered more serious. Upon her arrest for these charges Germaine said:

‘But I am English. I was married to an Englishman.’

The file is detailed, explaining how Germaine left home at about 14 after a family quarrel, was sent away to school and then worked in parfumerie shops in Paris. There are even statements recorded by the taxi driver who took the pair to the registry office (and ended up as a witness to the couple’s marriage) and by the immigration officer who allowed Germaine in to the country initially, who noted he saw no reason to be suspicious. At the time she had showed him her return ticket. The level of detail in the file is striking, with immigration cards, marriage certificates, birth certificates and a register of marriage all included.

The case went to court. Germaine argued that any false information about the marriage was given by her husband. After lengthy deliberation, she was found not guilty of being an alien failing to register and not guilty of making a false statement to police, but guilty of making false statements to immigration officers on landing. Germaine was sentenced to two months imprisonment without hard labour. The judge additionally recommended her expulsion from the country, saying ‘the defendant is a most undesirable person to remain’ but he acknowledged he had no power given her British citizenship through marriage. The judge appealed to the powers of the Secretary of State to intervene.

Throughout this period Germaine was badly ill with potential consumption. The surviving file leaves some gaps in her story but it seems she was believed to be still in the UK despite an order to leave. By 1926 her location was unknown to the authorities, but thought to be an unidentified nursing home in the provinces. That year a supplementary notice was added to the Police Gazette, urgently looking for Germaine’s whereabouts. A final note in the file states that should she have left the country, she should not be allowed to land except with a valid British passport. This notice was sent to all ports by Scotland Yard. The end of Germaine’s story is unclear.

In the archives we constantly come across people’s lives, but this case is particularly evocative. The fragments of Germaine’s life can be, to some extent, pieced back together through the surviving material. It demonstrates one of the many human stories that can be found in the records relating to both migration and sex work.

Once again TNA withhold information and censor it, there can be no issue releasing Germaine’s surname after this amount of time.

As usual the National Archives continues to shed light on subjects that many of us have never thought about or are simply unaware that relevant records exist.

In doing so it highlights the fact that it – like so many museums and collections – are not just repositories of dusty records but gateways to human stories and social change.