On 19 April 2022, The National Archives launched Find Case Law, taking on the responsibility for the external publication of court judgments from the Upper Tribunals, High Court, Court of Appeal and Supreme Court.

This blog, one of two, reflects on our first year of publishing judgments – 4,000 so far and counting. First, we’ll look at some of the technical problems we’ve tackled; and in a second blog we’ll examine how the service is being used.

Accessing judgments on Find Case Law

The aim of the Find Case Law service is to permanently archive, publish and enable the re-use of judgments as data for everyone. It’s a simple proposition that is sometimes complicated to deliver.

We receive new judgments into the archive as digital records. They are drafted, handed down in court, and transferred to us as Word documents. To provide access we transform the Word documents into several other formats: XML, HTML and PDF. We are creating three digital surrogates of these important records.

Our choice of surrogate formats is driven by what is most suitable for the three main types of access we provide:

- For reading judgments on the Find Case Law website, we use HTML 5 – the modern version of HTML. That means we can provide the content of the judgment in an accessible format, regardless of what device or assistive technology is being used.

- If you are re-using the judgments as data via our API, we provide LegalDocML. This is an international XML standard for legal documents, also used for legislation. Important information in the document (the neutral citation, date, parties etc) is marked-up in the text. We are also keen to align with government’s Open Data Standards principles. The XML mark-up provides the data for our faceted search. We know there is much more we can do using LegalDocML to improve searching and browsing judgments in future.

- If you want to download and print a copy of a judgment, we provide a PDF. We know that this is useful, for example, for legal professionals putting together court bundles. The PDF version replicates the appearance and pagination of the Word original.

Transforming judgments for presentation on the web

We initially built the software to transform judgments, from Word to LegalDocML, with relatively few source documents to work with. What we didn’t know when we started was the amount of bespoke Word formatting used in judgments that we would need to faithfully preserve through our data transformation processes. If we were to frame this problem as a user need it would be:

‘I need to see exactly what the judge signed off on, I don’t want to lose any subtle meaning contained within the formatting that could be important to my correct understanding of this judgment’.

The archivist in me soon noticed a uniqueness to judgments in comparison with other types of public records we receive at The National Archives – they are individually authored and formatted with a great deal of care and attention. Maintaining the integrity and authenticity of the record is paramount but we also want our users to be able to read judgments with ease on the web.

We learnt early on we could meet this need by way of a PDF created from the Word original (not a PDF created from the HTML, rookie mistake!). But we still wanted our HTML to be accessible, to look good, and to look good on all screen sizes. This is especially important as we know over 40% of our users view judgments on their mobile phones.

With a rapidly growing set of Word original documents to work from, we have made close to 100 releases of the transformation software in our first year of publishing judgments. Of course, a proportion of these releases are what you would expect for a piece of software being used for the first time, but most of them are additions to the code base in response to the sheer volume of variation in formatting we have seen across judgments.

We are aiming to produce good (i.e., semantically correct) HTML that supports accessibility. To achieve this, we standardise some aspects of the presentation of the judgment on the web but still retain enough flexibility to faithfully represent the formatting the judge applied in Word. It’s a balance, and a tension that’s not always easy to navigate. It requires a lot of collective head scratching and problem solving from the developers and designers.

We have now settled on the following approaches, although it is still very much a work in progress:

1) Indentation of paragraphs

We always indent subparagraphs a set amount, first level subparagraphs by x amount, their subdivisions by that same amount again, and so on. In contrast Word allows for paragraphs to be indented by any arbitrary amount, and occasionally we receive documents containing paragraphs indented only slightly more or less than those above them. Our automated conversion process must decide how best to align indented paragraphs. This is not always a simple matter, such as when the judgment contains a complex quoted structure with its own indentation pattern.

2) Tables

Often tables in judgments are formatted to facilitate the visual presentation of data on a standard page of paper. We need to adjust the tables, so they appear sensibly on a wide range of screen sizes and orientations.

3) Images

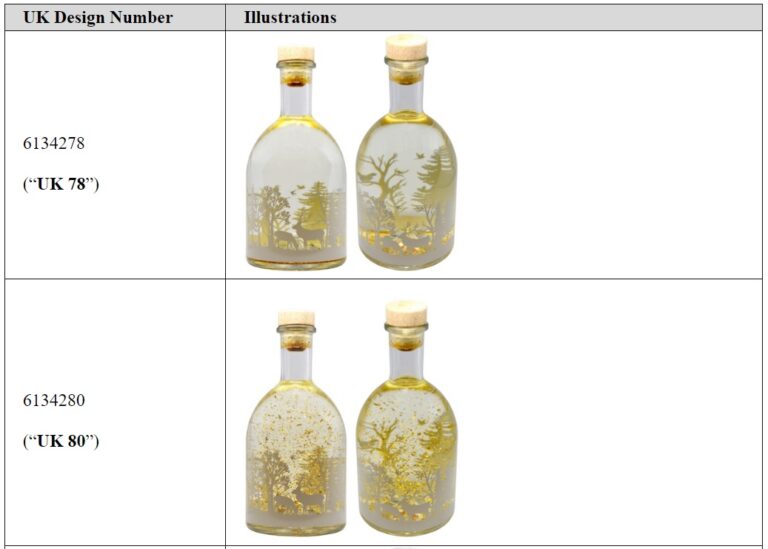

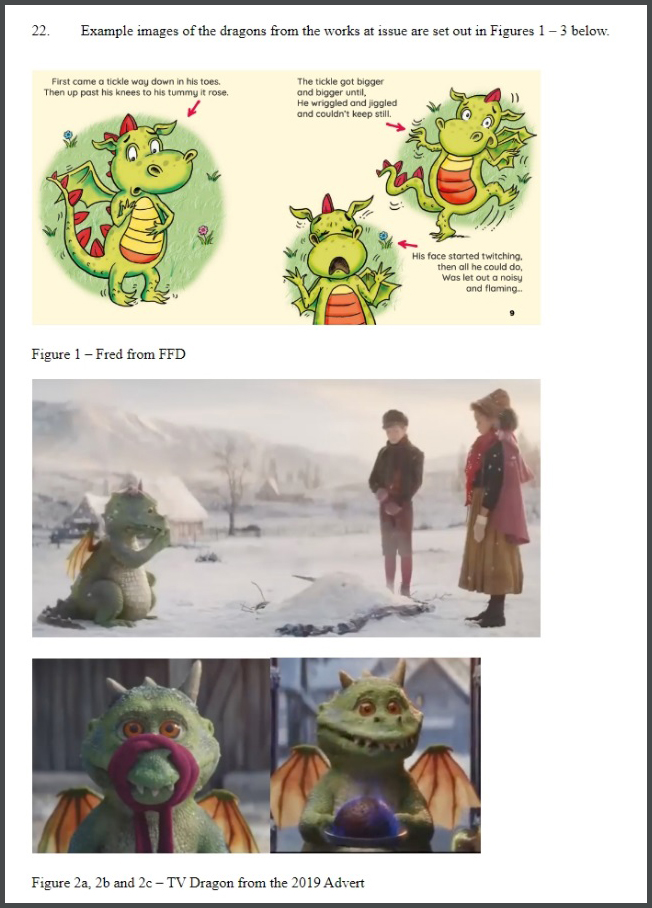

Judgments can contain a wide variety of diagrams, illustrations, images and photographs. Sometimes the images are wonderful.

© Fay Evans (2017) Fred the Fire-sneezing Dragon. Illustrations by Lisa Williams.

John Lewis PLC, Christmas advert 2019

Word allows users to position, rotate, crop, and merge images and drawings in many formats. How ever the images in a judgment have been created and edited, we need to make sure they are converted to a format that a web browser can properly display.

4) Emphasis on particular words or phrases

When creating the HTML version of the judgment we are retaining some of the drafter’s formatting choices but not others. For example, if a word or phrase is italicised or underlined, we will show it exactly, but a change in font or font size will be ignored.

5) Our commitment to improving accessibility

We’ve taken time to make sure our approach to creating the HTML version of the judgment aids the accessibility of the content, particularly for users relying on an assistive technology such as a screen reader. For example, the hierarchy of headings tells the reader where sections start and help convey their relative importance. We’ll continue to do lot’s more work in this area to give as many people as possible easier access to case law.

6) Collaboration

We are delighted to be working with judges and clerks, who would like to improve the accessibility of their judgments. For example, we recently had a great discussion about adding alt text as standard to common images such as court crests, which appear on nearly all judgments.

Formatting issues were tripping us up a fair bit in the first few months of the service. We have now got a lot of the issues under our belts. The HTML judgments are looking more pleasing to the eye and delays to publication due to a formatting issue are now quite rare.

In our second blog, we’ll explore how Find Case Law is being used with a focus on the increasingly diverse range of users we’re seeing.

Nicki Welch is a digital archivist and Service Owner for Access to Digital Records at The National Archives, who worked closely on the launch and first year of the Find Case Law service. Colleagues Terry Price and Jim Mangiafico also contributed to this blog.

There is zero mention in this blog of the failure by the National Archive to risk assess judgements before positing online, despite policy requirement to do so, and your failure to ‘police’ and manage overseas companies reproducing and making case law searchable without license to do so. Open Access does not imply a free-for-all, nor the breach of privacy and safety for those who’s judgements find their way on to your site. From personal experience it is a badly managed arrangement where data law and GDPR is flouted, with no ultimate data controller taking responsibility or being held accountable. The rush to serve the courts in providing open access to case judgements has been done in complete disregard for the rights of individuals under law to privacy, safety and security.

Open justice is a fundamental constitutional principle and we are confident that we comply with all our obligations. We take action to ensure that licensing conditions are adhered to by third parties when they are using judgments from the Find Case Law service.

I agree with Veronica. There’s an issue of enforcement for foreign companies that re-use decisions and judgments without a license. I can fairly say this is absolutely detrimental to UK companies. It would be fairer to restrict geographically or potentially to restrict access to specific format unless a licence has been issued. I think this an important point you need to work on.

This is an interesting blog post as it seems to reflect on the more ‘fluffy’ aspects of judgement publishing, and almost infantilises it somewhat. There seems to be a level of detachment from the gravity of judgements publishing and a failure to understand the impact ‘open justice’ has or what that means. I suspect much of this is down to the fact that the National Archives is not a legal body and has little legal knowledge/understanding in the manner the previous key publishers had/have, e.g. BAILII. I do agree with the above two comments, both on the risk and on the failure to curtail overseas exploitation. The fact of the matter, which the last comment fails to appreciate, is that there is no actual issuing of licenses with open justice license (OJL), and it is more of a promise to follow a set of rules rather than an actual license that gets issued, and that is a significant part of the issue. The first commentor references ‘free for all’ and I would suggest that is exactly what the current publishing standard is. I work in a legal aid service and I simply advise clients to request anonymity given the degradation of standards for judgements publishing and the open-ended risk that one has no idea where one’s judgements/information will show up. I’m not sure if there is to be a public/government review of the progress to-date since the National Archives took over open justice publishing, but I would certainly wish to contribute if such a thing were to happen. I believe this approach was not properly thought through from any perspective other than simply throw it all out there and see how it goes.