The Popish Plot was a period of extraordinary political tension that took hold in England in 1678. It was a crisis that revolved around a series of increasingly elaborate allegations against English Catholics, who were supposedly in league with the French, of a plot to murder King Charles II and replace him on the throne with his Catholic brother James, Duke of York.

It preyed upon long-held English fears of a Catholic uprising to reverse the Reformation (such as the Gunpowder Plot), as well as the possibility of encirclement by the European Catholic powers. There was also domestic fear of a Catholic succession after York was exposed as a Catholic in 1673.

Some blame must also be laid on Charles II, whose ambiguous religious attitude and toleration of Catholics within court sowed doubts among many, and gave his enemies political capital to exploit. Despite all this, both the Popish Plot and associated Exclusion Crisis were based on falsehoods and deception.

Several leading opponents of Charles II, led by Anthony Ashley Cooper, the Earl of Shaftesbury, used the alleged plot as an opportunity to put pressure on the king (through Parliament) to exclude York from the succession. Ultimately this failed. But few of those who sought advantage from the political crisis that engulfed England between 1678–1681 emerged with their reputations enhanced.

Titus Oates, finding an audience

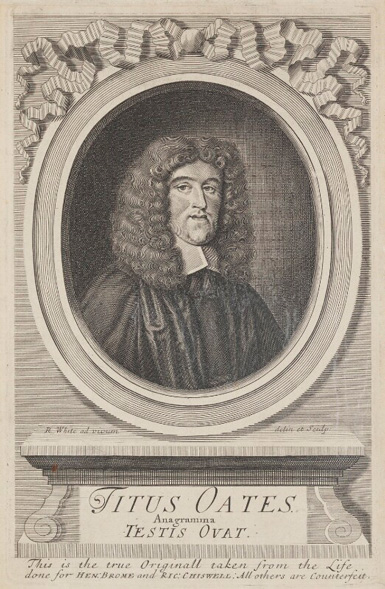

The key protagonist in this tale was Titus Oates, a man who had sought a career in the Church of England but was ejected first from Cambridge University and then, having lied to the Bishop of London about his qualifications, from his livings, after unacceptable behaviour and a perjury case against him.

After a series of further personal failures, including a stint as the chaplain to the English garrison at Tangier, Oates wound up destitute in London in the mid-1670s. It was then that he sought sanctuary within the Catholic Church and endeavoured (probably deceitfully) to train as a Jesuit priest. Despite having welcomed him into their schools, he was ultimately expelled for boorish behaviour. But Oates’ time with the Jesuits – at English colleges in Valladolid in Spain and St Omer in France – provided him with just enough knowledge of the Catholic infrastructure in England to use to deadly effect.

By 1678 Oates was again destitute in London, but now fell in with Dr Israel Tonge, an unhinged academic. Tonge firmly believed that the Jesuits were to blame for the Great Fire of London 1665, an event that appears to have left him thereafter unbalanced.

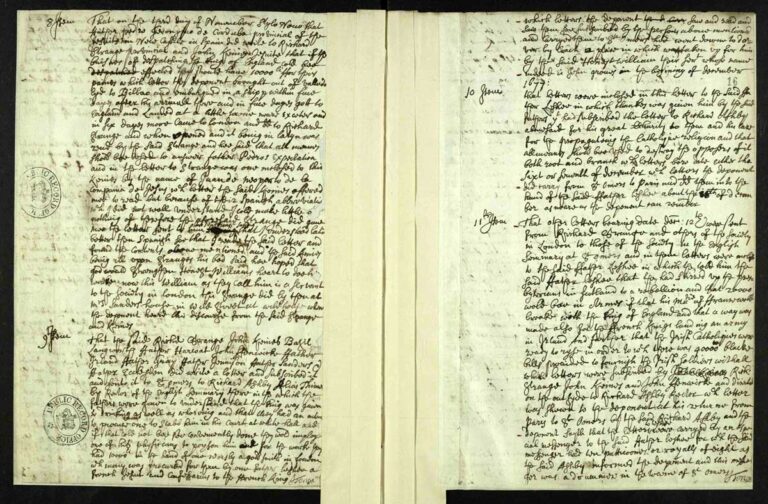

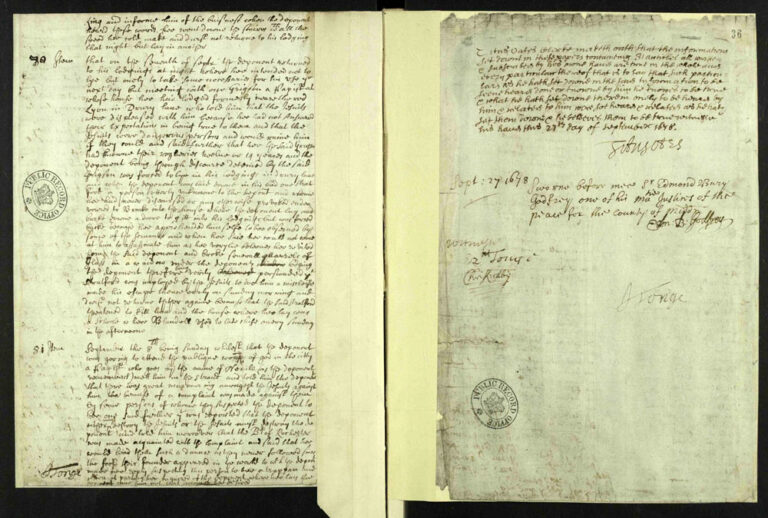

In Tonge, Oates found an audience that satisfied his craving for attention; in Oates, Tonge landed on a source for his prejudices and misplaced sense of danger. Encouraged by Tonge, Oates concocted an elaborate web of lies that alleged that he had uncovered a Jesuit-led plot to murder Charles, which he wrote down and then swore before a magistrate, Justice Godfrey Berry.

Justice Godfrey was now put in an awkward position. He was obliged to make these allegations known to the privy council but he paused for several days, likely suspecting that they were untrue. In doing so, he was potentially guilty of misprision (ie concealing one’s knowledge) of treason.

The matter was nonetheless brought to the king’s attention in late August. Although Charles largely dismissed the story he instructed his chief minister, Thomas Osborne, Earl of Danby, to investigate. Danby could find no evidence of a plot, and that should have been the end of the matter.

Spiralling out of control

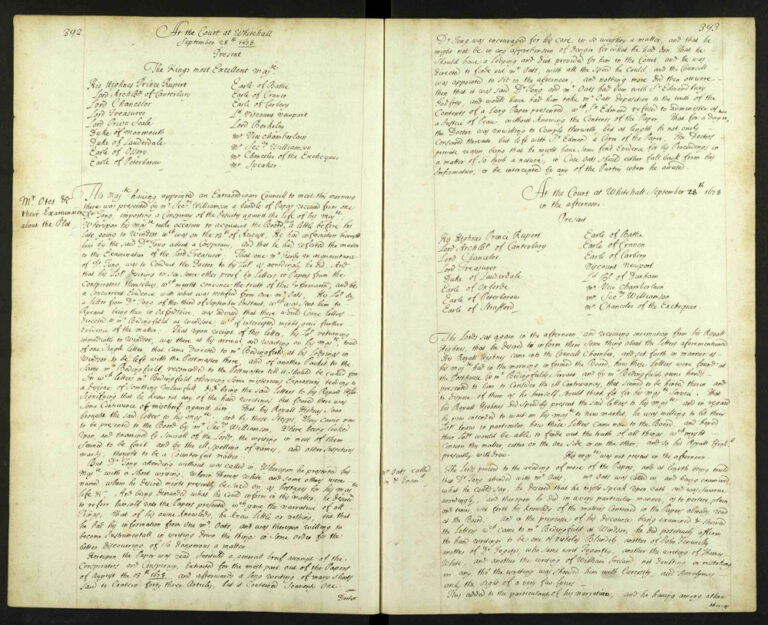

Whispers of the plot began to emerge and Oates was summoned to present his allegations at the Privy Council at the end of September 1678. Charles remained unconvinced, but several of his councillors lacked his wisdom. There were significant inconsistencies in Oates’ allegations and when he was pressed on these, or when challenged by the accused men who were hauled before the council, he was deeply unconvincing.

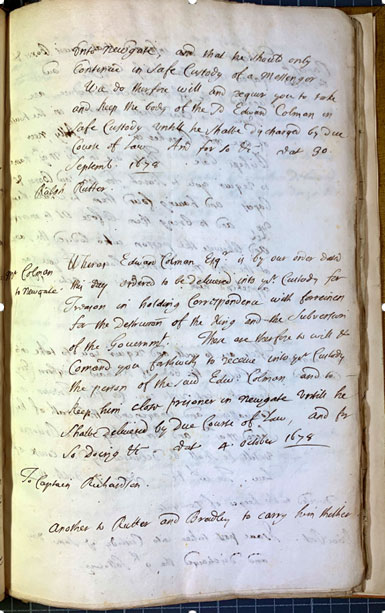

From this point, events began to spiral out of control. The House of Commons took up Oates’ stories, championing him despite his inability to corroborate the allegations when he appeared before them. Nonetheless, Oates got lucky in several cases, such as his allegations against Edward Coleman, a Catholic convert who had both served York and corresponded with the French. The second piece of luck Oates had was the unexplained murder of Justice Godfrey (unresolved to this day), which sent panic into the streets.

The council also panicked, issuing numerous arrest warrants for as many of those as they could find whom Oates had named. The charges were extremely serious. Conspiracy to murder the king fell under the terms of the 1352 Treason Act, specifically to compass and imagine the death of the monarch. This meant that just discussing actions against the king could lead to accusations of treasonous behaviour, regardless of whether there was any actual threat to the king’s life.

Arrests on charges of treason, no matter how tenuous, meant trials, mainly at the Court of King’s Bench. It’s worth reiterating that in the pre-modern period, the accused were up against the whole apparatus of the state. Presiding over the trials was Sir William Scroggs, Lord Chief Justice of the Court of King’s Bench. Unlike the modern judiciary in the UK, officials served at the pleasure of the monarch in the pre-modern period and their role was to secure convictions. Failure to do so could result in dismissal from office.

Scroggs had proven himself as an adept and nimble lawyer early in his career, which saw his advancement through the usual legal circles in London: Grays’s Inn, and appointments to the council for the City of London, until eventually he was appointed a judge at the Court of Common Pleas in 1676 at the behest of Charles II’s chief minister, Thomas Osborne, Earl of Danby. Scroggs’ opening address to the court won lavish praise, as he argued that the lawyers had responsibility for protecting the Crown.

By 1678, Danby manoeuvred Scroggs into the position of Chief Justice of the Court of King’s Bench, much to the hackles of Scroggs’ opponents, who suspected favouritism. The timing was unfortunate for Scroggs, who was not long in his new post when the allegations of a Catholic plot emerged.

Opportunism and dishonesty

Scroggs represents many of the deficiencies of early modern justice. All authority was understood to come from the monarch and the judges acted in his or her name. The cases that were heard following Oates’ allegations were also extraordinarily political. Based on reports of how the cases were conducted, Scroggs was not impartial. Instead, he sided with Oates and the House of Commons, and aggressively pursued convictions. Scroggs’ behaviour while presiding over the cases was at times distasteful, and he is recorded as barracking (jeering at) condemned men.

Despite Oates’ evident inability to consistently corroborate his allegations, Scroggs oversaw more than 30 trials, sending almost 40 men to their deaths. This was tolerated by Charles as it deflected the more serious challenge to his (and York’s) position, but the king’s opportunism was matched by the dishonesty of his political opponents.

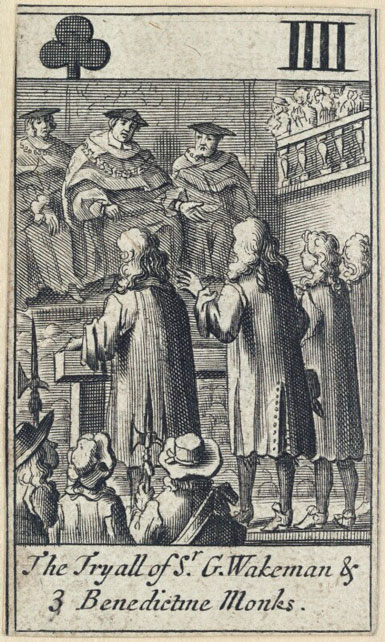

Eventually, though, the political tensions saw Scroggs make enemies of those who sought to remove York from the succession due to his failure in July 1679 to convict perhaps the most high profile defendant, Sir George Wakeman, a physician to the queen. In this instance, the case had drifted perilously close to the royal court. If someone in such proximity to the king had been convicted, it would have had extraordinary political consequences for Charles II and Queen Catherine. Scroggs dismissed the case against Wakeman and the king was said to have wept with relief.

From this point, Scroggs could not be relied upon to secure prosecutions, as the Earl of Shaftesbury sought to maintain the pressure on the king and his brother. The Wakeman case marked a watershed moment in the Popish Plot and Exclusion Crisis, although it may not have felt like it at the time. Scroggs had to go on the defensive, but it was to no avail. He was impeached in 1680 and the king had no choice but to remove him from office.

The Popish Plot saw the merging of several political threats to Charles II: his own ambiguous religious attitudes and overt toleration of Catholicism; the threat posed to the succession by the Duke of York; Charles’ alliance with the French; and the duplicity of the Earl of Shaftesbury.

Oates was the touchpaper for the combined crisis, but Scroggs was the instrument through which so many men were tried on charges of treason and executed. Unable to refute the charges of compassing and imagining the death of the king in the face of Scroggs and the Court of King’s Bench, they were condemned to death.

If you wish to know more about the Popish Plot, you can watch this video. There’s also still time to visit our free exhibition Treason: People, Power & Plot, which runs until 6 April 2023.

Thank you very much for this article and the video on The Popish Plot. I have researched this topic for many years as one of my family, David Lewis, S.J., was one of those who lost his life in 1679. However, he was canonised by Pope Paul VI in 1970, as one of the Forty English & Welsh Martyrs.

It was wonderful to see some of the original documents relating to the plot. I would like to have copies of these and of the portraits of the individuals involved. I’ll do some more research at the National Archives.