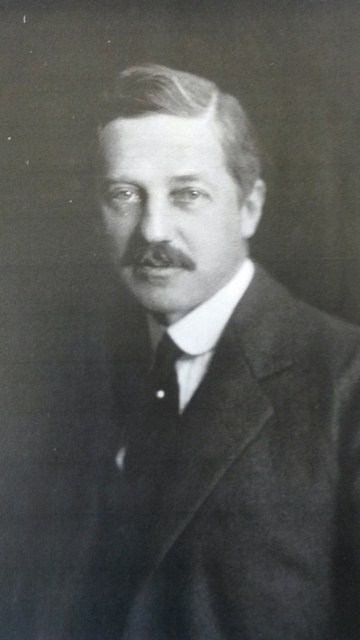

A family photo of Gus from around the time of the First World War

Last year, I begged this ‘My Tommy’s War’ slot to write about my mother’s family’s war, because of a letter in my mother’s family papers which was written exactly 100 years ago, June 1914. The letter was sent from my great-grandfather, Vincent, to my grandfather, Gus. It says that Vincent and my great-grandmother Caroline won’t be coming to visit Gus in July 1914 as planned, as they are going to a sanatorium for their health. They’ll come in September instead.

So far, so not-too-sinister (at least if you know that this branch of my family obsessively took health cures but mostly lived to a ripe old age!). But if I tell you that my family’s surname was Mayer, that Gus was short for Gustavus, and that Vincent was writing from Freiburg im Breisgau to his son in London, you can possibly start to see why this letter is symbolic of what the First World War meant to my family.

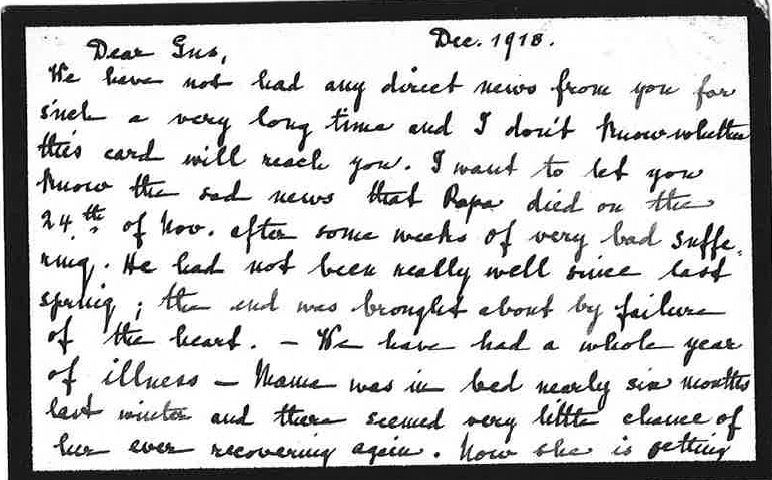

In fact, Vincent’s decision to postpone his trip to England by a few weeks meant that father and son never met again. Vincent died in November 1918, still in Germany, aged 87. In December 1918, the German branch managed to get a letter out via Switzerland, which gave Gus news about what had happened to his family during the war, including his father’s death.

Family divided

When remembering the First World War, it’s easy to think in terms of families being on one side or the other, according to their nationality. In practice, as my family’s experience shows, it is possible to find families who were physically ‘on both sides’, divided and unable to communicate during the war. Luckily, all my family members were too elderly (in some cases too female) to be required to take up arms against each other, but I’d be surprised if that never occurred with other families. My relatives were certainly deeply inconvenienced and divided by the war’s outbreak, even before the full impact of the conflict was felt. The census shows that Gus’s sister was staying with him in April 1911 – but from 1914 until the 1920s that easy international relationship collapsed.

Family in Britain

In many ways, Gus was the lucky one in this divided family. He was born in America, had retained his American nationality and was at this stage married to an Englishwoman. [ref] 1 Isabel Codrington Pyke-Nott (1874-1943). The tale of her war art work will have to await another blog post, but I’m hoping I get the chance to explore it soon. [/ref] So despite his suspiciously German name and close relatives living in Germany, he was able to continue his business as an art dealer in London.

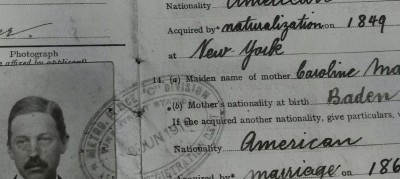

Registration of aliens in the UK: with parents’ nationalities

There were some cosmetic changes to Gus’s life and work, however. The company name was changed from Colnaghi & Obach back to just Colnaghi. Gus’s business letterhead was discreetly amended to read Gustavus Mayer (U.S. Citizen). He had to carry an alien’s passport when travelling in the UK. I was particularly interested in the section which asks for details of relatives by marriage serving with British forces – in this case Gus’s brother in law James G Pyke-Nott was cited as evidence he had a stake in the Allied armed forces.

Gus’s partner in the firm, Otto Gutekunst, was also of German extraction. At the very start of the war (5 August), Gutekunst wrote to Gus, grappling with what the war would mean for people and for business, ‘Shall we survive this or shall we be broke when the war is over? Your poor parents…must be uncomfortable too, so near to France… I only hope there will be no riots over here by & by with destruction of property… Could we if desirable offer our upper floors and transform them in to temporary hospital?’ And, with much feeling, ‘Thank God I am naturalised.’ This last note explains why I have not been able to find Gutekunst among the lists of interned enemy nationals which are kept at The National Archives (HO 144/11720): there was a family legend that he was interned, but evidently not so! I found his naturalisation instead at HO 144/1542/B14682.

By 1917, Gutekunst was writing, ‘There is practically no business going, and for some time to come’. It was no time to work in luxury goods. Art dealing had always been an international trade; with Europe closed to the art market, Gus was allowed to travel to the US to continue his business on at least one occasion. Passenger lists show him crossing the Atlantic in spring 1915 with art to sell on the much healthier American market – a braver man than I! In fact, passenger lists in BT 26 show that his return journey arrived at Southampton on 16 May 1915, just nine days after the sinking of RMS Lusitania (I wonder what on earth the insurance for the artworks was like).

Family in Germany

I’ve been lucky with my family history because my grandmother (Gus’s much younger third wife) lived until 1998 in a house she had moved into in 1954 – she never had reason to throw much paper away. So the letters that Gus received between 1895 and 1914 from his parents, brother William (d Salatiga, Java, 1905) and sister Helen (d Freiburg, Germany, 1973) survive very well, as do letters Gus received after 1919 from Caroline and Helen. But because of the enforced silence during the war, it is more difficult to piece together the story of the German side of the family in those years. I know that they remained in the same house, or at least were still living there after the war when contact was re-established. It appears that Vincent died of heart failure, after a long period of illness in 1918.

The one thing we do know for sure concerns art and money, and there are a number of sources for this. 1914 was a particularly bad time for Gus to be out of touch with his family in Germany, because he had borrowed most of the family’s ready cash to buy into his part of the Colnaghi & Obach partnership. He was supposed to send regular funds back to Freiburg for the family to live on, but of course that wasn’t an option during the war: money transfers from the UK to Germany were forbidden. Vincent, who was significantly wealthy before the war, therefore found himself without liquid assets. He was long retired, aged 83 at the start of the war, and Caroline was 73. They were in no position to find work.

So towards the end of 1917, with what I assume was considerable reluctance, Vincent sold his print collection, to make a large cash lump sum to live on. Prints were his passion, and his profession, and he had a distinguished collection of Dürer prints, among others. You can read more (in French) about his collection and its dispersal in Frits Lugt, Les Marques de Collections de Dessins et d’Estampes (L.2525). Lugt lists all the known collectors’ marks stamped onto print and drawing collections. In among them is a simple mark ‘V.M.’, with which Vincent’s collection was marked as it was sold on.

Lugt may not sound like the most exciting reference work ever, but it’s useful for my family history because Lugt knew Gus quite well, so we believe the biographical information given about Vincent comes directly from the family. That doesn’t mean that it is correct, but it gives the tale Vincent probably told his children about his early life. We know so little else, travelling between Württemberg and America from 1830 to 1885, that this is a precious source.

Post war recovery and crisis

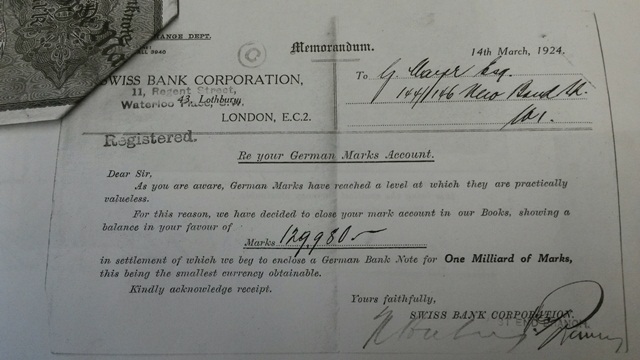

The end of a family fortune: an account closed with a note that the 129,950 marks it held are now ‘valueless’

My grandfather and his family survived their divided war, though Vincent’s death while separated from his only surviving son is a sad note. But their troubles were far from over after 1918. Having had the family money all in the UK during the war, Gus’s mother and sister assumed he would support them after the war. But it still wasn’t an easy economic situation for luxury goods vendors. Even more importantly for the family’s fate, it was a terrible time to have a lot of money in a German bank account. The cash fortune realised through the sale of the Dürer prints simply slipped away under post-war conditions in Germany, most of all the hyperinflation of 1923. We have the settlement of Gus’s German account: a letter from his bank with a bank note stamped 1 milliard marks. As the covering note explained, it was the smallest currency available, and essentially worthless. So the German family became ever more dependent on their one London-based member, and the last 10 years of Caroline’s life are mostly recorded in letters arguing about money.

The first contact between German and English branches of the family, announcing Vincent’s death (December 1918)

I can’t say, ‘If only Vincent and Caroline had come to London in July 1914 after all.’ Although naturalised Americans, they were resident in Germany and I can’t imagine it would have been easy for them to be marooned in enemy territory. My great aunt Helen would have been left alone in Germany without any family around her throughout the war. But when I look at that letter from June 1914, with all its false assumptions about the ongoing ease of international travel and family communication, I do reflect on how far the impact of the First World War was felt by civilians who might have appeared to be well out of harm’s way.

[…] My Family’s War: across enemy lines […]