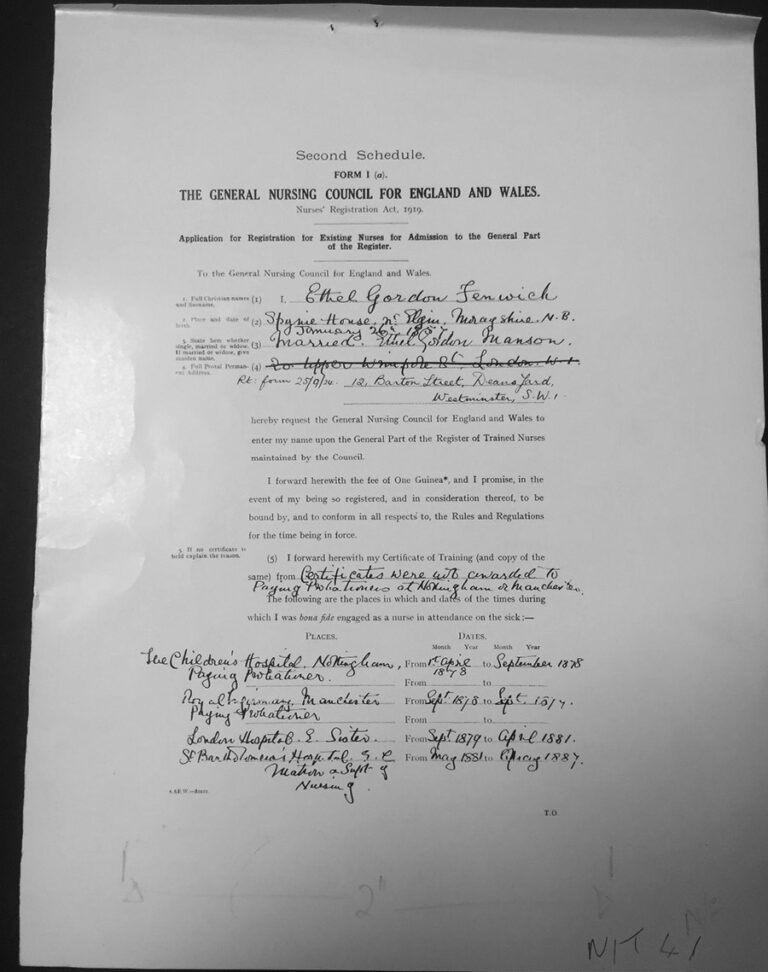

On 23 December 1919, after decades of campaigning, the Nurses Registration Act was passed, securing legal and state regulation of the nursing profession for the first time. With its passing, the General Nursing Council was formed to set up and maintain a register of nurses; and so – on 30 September 1921 – the first State Register of Nurses was opened.

The first nurse to appear on the register was Ethel Gordon Fenwick, a woman who had spent the past 30 years campaigning for the state registration of nurses. But what was her role in the campaign and why was she nurse number one?

Who was Ethel Gordon Fenwick?

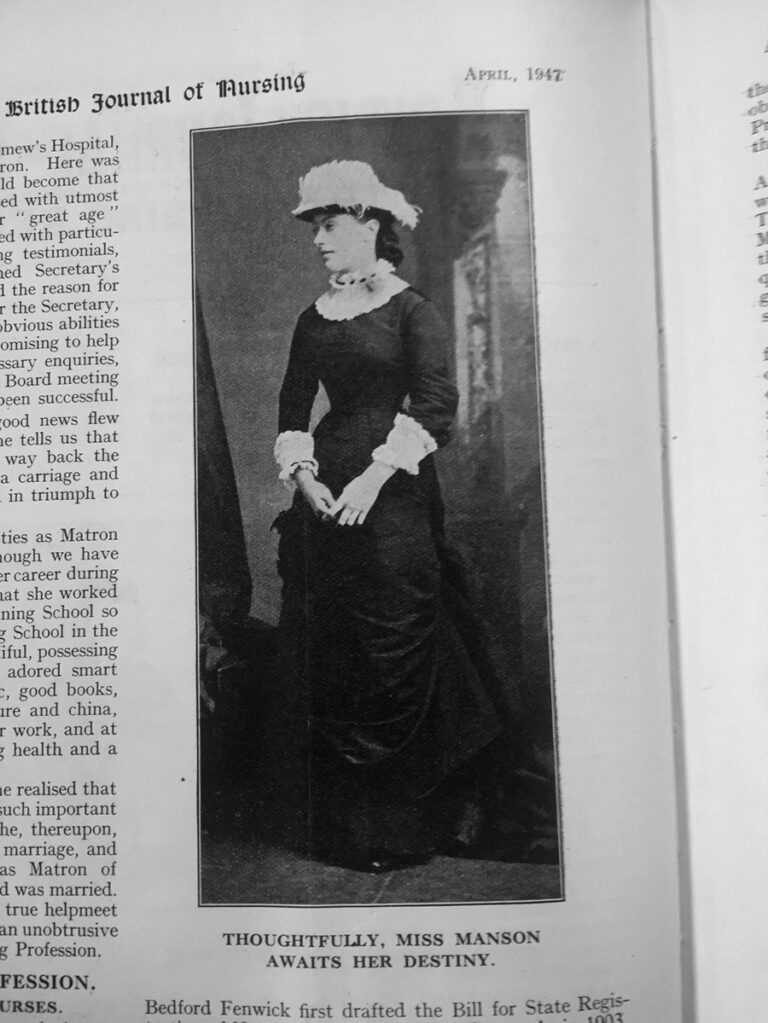

Ethel Gordon Fenwick was born Ethel Gordon Manson in Morayshire, Scotland on 26 January 1857. She grew up in a well-off household and chose to dedicate her life to nursing.

In the 19th century access to training and education in nursing depended upon the social standing of the nurse. For someone like Fenwick, from a middle or upper-class background, training was available for a fee as a paying or special probationer. For the lower-classes, training was free and they were paid a salary.

However, paying probationers had the advantage of expecting promotion, even as soon as their probationary period was complete. Fenwick began her training at the Children’s Hospital in Nottingham in April 1878 at the age of 21, moving to Manchester Royal Infirmary after about six months. By the time Ethel was 24 she had obtained the position of matron at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital[ref]International Nursing Review, 18 September 1974, p. 68 in DT 16/396.[/ref].

In 1887 Ethel Gordon Manson married Dr Bedford Fenwick, a surgeon. Following her marriage Fenwick retired from nursing, as was customary at the time. From this time Fenwick began organising campaigns to reform the nursing profession, advocating for consistent training standards and the establishment of a centralised register of nurses.

Professionalisation of nursing

In the 19th century nursing had undergone a shift towards professionalisation. The first professional school of nursing was founded at St. Thomas’s Hospital in 1860 by Florence Nightingale (1820-1910), who sought to improve the status and proficiency of nursing following her experience in the Crimean War (1853-1856). Read more about Nightingale in a previous blog.

Over the course of the century more hospitals established their own training schools but there was still no consistent standard of training in place for the profession. At this time nursing was organised throughout disparate groups across the country, and the numerous organisations had differing views about how best to approach reform. In fact, Nightingale herself did not support the idea of state registration, considering it would cause barriers for working-class women.

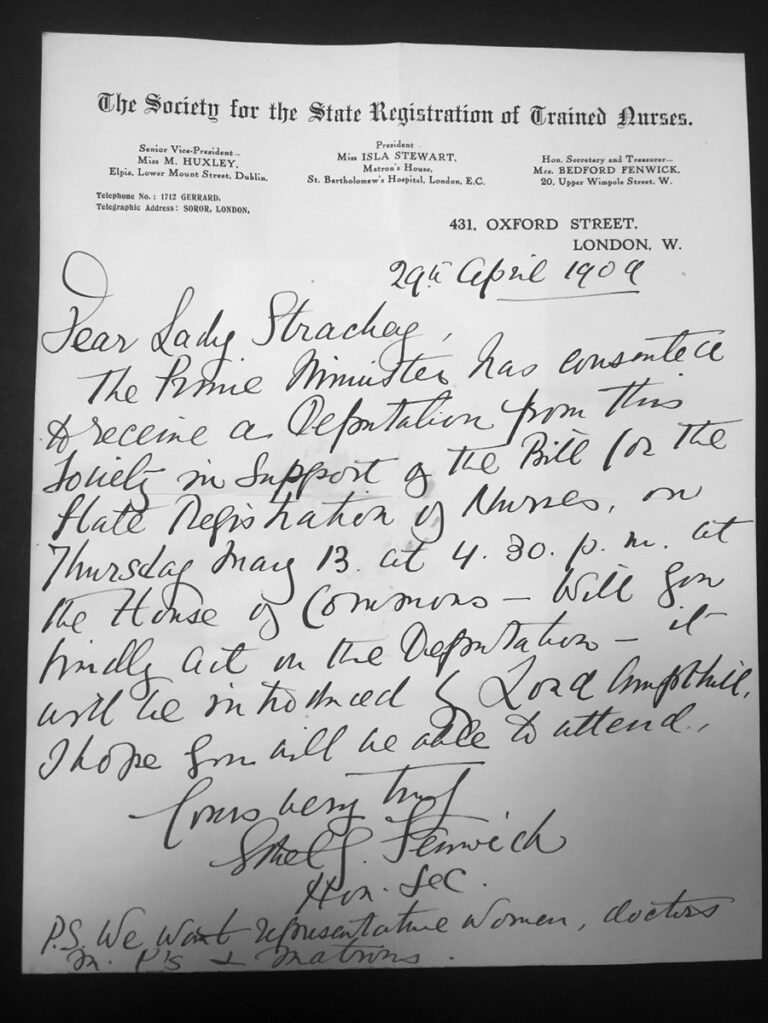

During the 1890s and early 1900s, Fenwick was involved in founding a number of societies to help further the cause of state registration. These included the British Nurses’ Association, founded in 1888; the Society for the State Registration of Nurses, founded in 1902; and the National Council of Nurses of Great Britain and Ireland, founded in 1904.

Fenwick also advocated for reforms on a global level, becoming the President of the newly established International Council of Nurses in 1899, which was formed through national associations. Through these networks Fenwick travelled around the globe pushing for reform. In a speech to the Matron’s Council at the International Council of Nurses in 1899, she exclaimed:

‘The nursing profession above all things requires organization: nurses, above all other things, require to be united. It depends upon nurses, individually and collectively, to make their work of the utmost possible usefulness to the sick, and this can only be accomplished if their education is based on such broad lines that the term “a trained nurse” shall be equivalent to that of a person who has received such an efficient training, and has proved to be also so trustworthy that the responsible duties which she must undertake may be performed to the utmost benefit of those entrusted to her charge.'[ref]Ibid, p. 69.[/ref]

From 1893 Fenwick began to edit the Nursing Record. She used it as a mouthpiece to disseminate her views on nursing reform and, as an active suffragist, women’s place in the hospital. From 1903 Fenwick became the driving force behind the multiple Bills that were put forward for the state registration of nurses. The British Nursing Journal retrospectively commented on her ‘fighting qualities’, stating that:

‘her devastating fluency and her controversial genius kept her mistress of each and every situation. She worked ceaselessly by day and far into the night for the success of her precious Bill.'[ref]The British Journal of Nursing, April 1947, p. 39 in DT 15/3.[/ref]

Disagreements between the nursing organisations and the start of the First World War created obstacles to the Bill but Fenwick was sat in the House of Commons when the Nurses’ Registration Act was eventually passed on 23 December 1919. She would go on to sit on the General Nursing Council, playing a prominent role in shaping how the register would be formed and maintained – as can be seen from the minutes of the Council held at the Archives in DT 6/1.

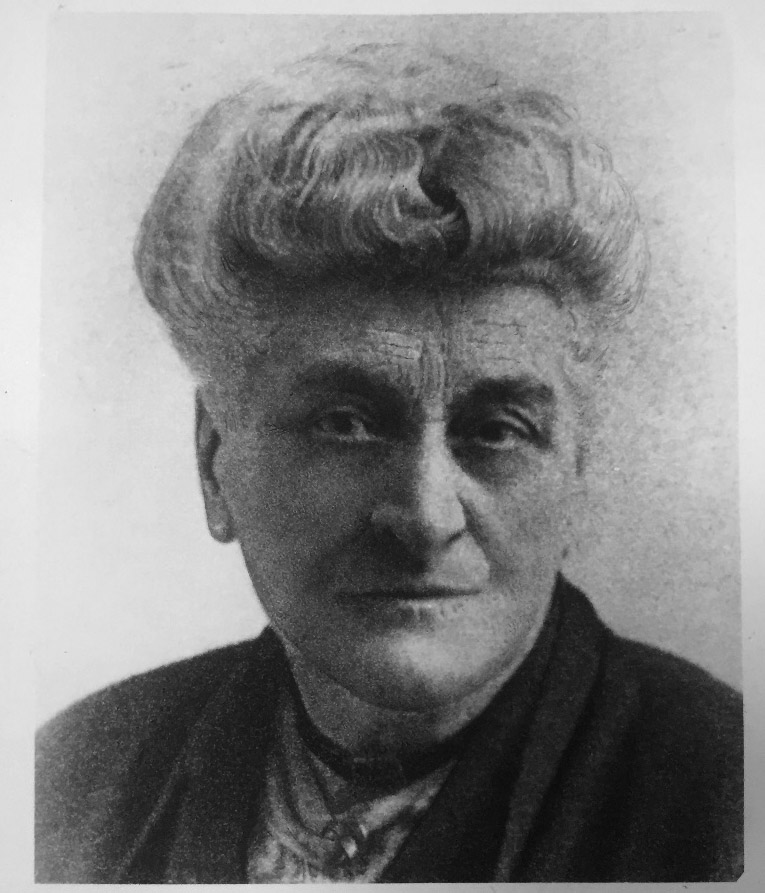

In 1926 Fenwick set up the British College of Nurses, a rival body to the College of Nursing. It was composed wholly of registered nurses, in contrast to its opponent. A note found in correspondence between the British College of Nurses and the General Nursing Council sheds light on Fenwick’s formidable character; after Sir Wilmot Herringham was appointed the Chairman of the General Nursing Council in 1922, Sir Almeric Fitzroy, Clerk to the Privy Council, observed that:

‘He has the reputation of being able to make himself unpleasant if the necessity arise and it is believed that he will be able to put a bridge into the mouth of Mrs Bedford Fenwick without being too sorely bitten. It is years since I was in touch with her but I have never lost the impression she gave one with whom co-operation is vain, unless upon terms of absolute submission.'[ref]The note pre-dates the formation of the British College of Nurses, see: Typed extract from Sir Almeric Fitzroy’s book [likely to be his History of the Privy Council], vol. ii, 31 January 1922 in DT 16/18.[/ref]

When Fenwick passed away in 1947 a testimonial in The Times read ‘she was essentially a reformer, dogged and uncompromising, and history will no doubt acclaim her as one of the most foremost women of her century.'[ref]The Times, 16 March 1947, in DT 16/396.[/ref]

The Register of Nurses

The register was initially divided into the general part, reserved for female nurses, with supplementary parts for fever nurses, male nurses, mental health nurses and sick children’s nurses. The books were updated to include new information such as change of name by marriage or removal from the register for non-payment of the retaining fee (until the fee was abolished by the Nurses Act 1949) or following disciplinary procedure.

Records held at The National Archives

Before the establishment of the General Nursing Council, records of nurses were kept by individual nurse training schools, most of which were attached to major hospitals. Many surviving records from hospitals are still to be found in local archives. For more information see our research guidance on records relating to Doctors and Nurses.

The National Archives holds records of the General Nursing Council for England and Wales, including:

- The Register of Nurses 1921-1973 in DT 10, including registration number, name, permanent address, date and place of registration, and qualifications.

- The Roll of Nurses 1944-1973 in DT 11. Applications for admission to the Register of Nurses was only applicable for qualified nurses who had completed a three-year training course. There was a large group of second grade or assistant nurses with two years training who were therefore ineligible for registration. The Nurses Act of 1943 recognised the assistant nurse and the General Nursing Council regulated the formation, maintenance and publication of the roll. In 1961 the name of the nurses was changed from assistant nurse to State Enrolled Nurse.

- The computerised register and roll 1973-1983 in DT 12.

The nursing registers are available on Ancestry.co.uk (£), scanned from originals held at The Royal College of Nursing.

Further reading

Winifred Hector, The Work of Mrs Bedford Fenwick and the Rise of Professional Nursing (London, Royal College of Nursing, 1973)

Susan McGann, The Battle of the Nurses (London, Scutari Press, 1992)

I read this with interest since it is so often that Boards are not including enough people who actually work in the profession. I would like researchers to remember that women would have to leave nursing, by law, once they married.

I believe the law was changed in 1942, because they were unnecessarily losing qualified nurses in the middle of WW2.

There are, alas, few male nurses these days, even in the 1960s there were quite a few but from my visits into hospitals they are few and far between nowadays.

An interesting (and for me with family who were part of the nursing community) an eye-opening one.

I simply didn’t know that that coveted (at least in my family) SRN title is merely 100 years old.

Interesting to note that the passing of the Act and establishment of the Register came after the First World War and at a time when women were (at least starting) to be recognised as having a greater role on society than wives and mothers in the UK and the early steps on the path of universal suffrage.

A very interesting article, I would like to see more of these. I am a State Registered Nurse and proud of it, I qualified in 1972 but shortly after we were not allowed to use that title and I have to write Registered General Nurse (RGN) or Registered Nurse ( RN). I am still working full time and very busy with it. I recently came across my first contract when I started my training and my allowance was £1,390 annually going up slightly in my 2nd and 3rd years, and we worked 42 hours a week. Intensive care units hadn’t been thought of then and our dress code was stockings of a certain colour, tights were only just coming in!

So were not the Queen Alexandra IMNS nurses trained nurses? My husband’s grandmother spent years training at Hull.