In November 1920 the youthful Ernest [Ernie] Smyth was arrested. At 22 years old he worked as a clerk in Belfast, describing himself as 5’5” in height, of medium build, about 26” waist, with dark hair and blue eyes. He had an interest in art and literature, he loved the Pre-Raphaelites and Oscar Wilde, but ‘abhorred ragtime jazz’.

Why was this young railway clerk arrested?

Found in his possession were hundreds of letters. Problematically for him these letters were between himself and many other men – ‘sodomites’, as the police file termed them. These letters provided criminal evidence of Ernie’s relationships with other men in a time when the law essentially criminalised their love.

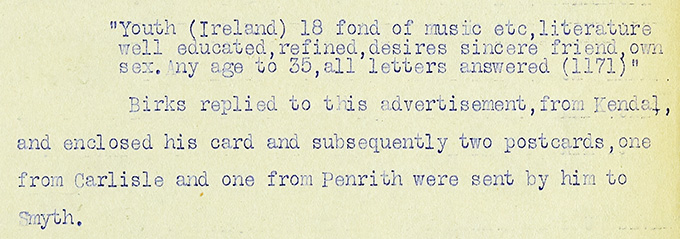

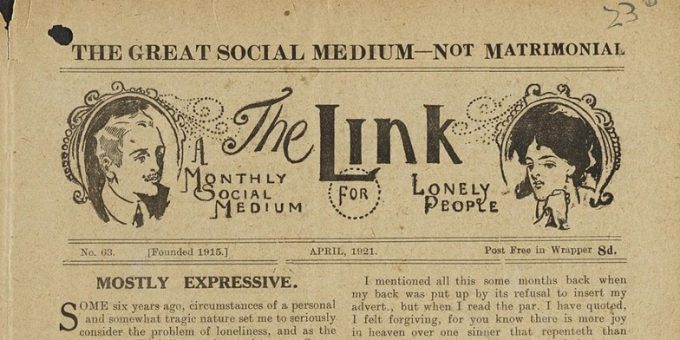

These men from all over the country had supposedly got in contact with Ernie through their classified adverts in The Link, a lonely hearts-style publication from the 1920s (you can read more about it here). In October 1920 Ernie had placed a personal advertisement in The Link, containing just the following words:

‘Youth (Ireland) 18 fond of music etc, literature well educated, refined, desires sincere friend, own sex. Any age to 35, all letters answered (1171).’ [MEPO 3/283]

Classified advert in The Link, as typed up in police files. Catalogue ref: MEPO 3/283

In his allocated 25 words Ernie had dropped in certain words, phrases and hints: ‘music’, ‘literature’, ‘sincere friend’ and, most significantly, ‘own sex’. These words would serve both as a signal of his desire to meet other men, but also ultimately to incriminate him.

Through The Link Ernie had been able to meet many men. Indeed, the 200 letters found on him signal a substantial queer network, which seemed surprising for 1920s Britain.

‘What you desire in the way of a chum is also my own desire’

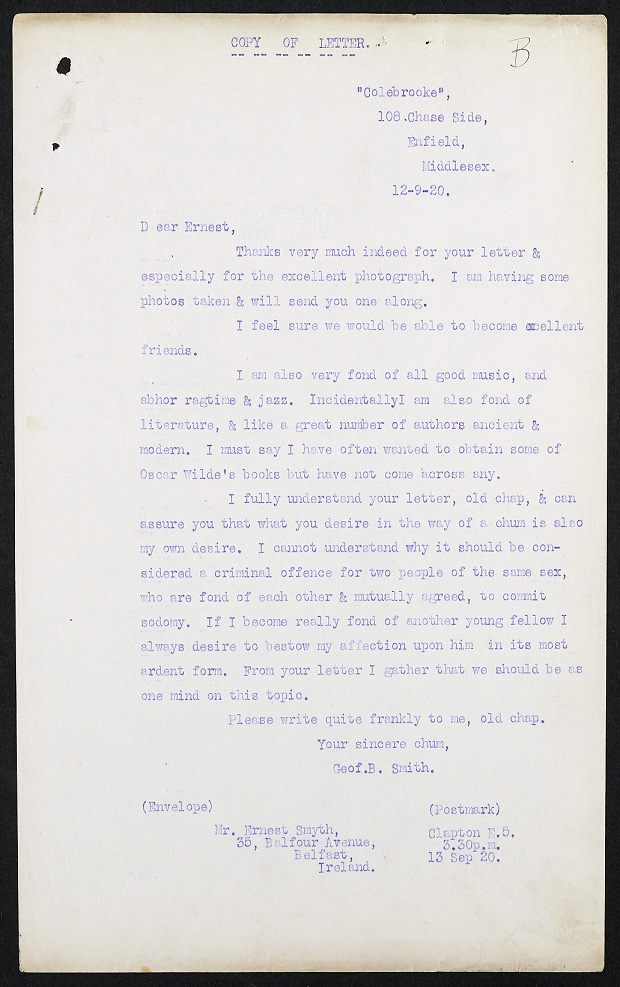

We can follow his relationship with one of these individuals pretty closely: Geoffrey [Geof] Smith, an ex-serviceman from Enfield. Because of Geof’s proximity to London, the Metropolitan Police requested that the Belfast Police send Ernie’s and Geof’s correspondence to the Met, which leads to these letters’ survival in our collections.

![Image of a selection of love letters found by the Police on Ernest [Ernie] Smyth in Belfast. Reference: MEPO 3/283.](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/18160329/Image-3-letters-Mepo-3_283-e1574165678316.jpg)

A selection of love letters found by the police on Ernest [Ernie] Smyth in Belfast. Catalogue ref: MEPO 3/283

The letters sent between them over a number of months provide a picture of their friendship and relationship. The Link and subsequent letters gave them a chance to correspond, despite the distance between Enfield and Belfast.

Through their vivid and open correspondence we can see that Ernie and Geof pursued a relationship, although whether they were ever able to actually meet is unclear. The intention, however, is clear. Geof writes longingly: ‘May the time [soon] come, Ernie, when we can meet and allow our sensuality to have full swing with each other’. On 2 October 1920 the correspondence continued: ‘I am longing to revel in the joys of your naked body.’

They talk about their fondness for each other and their mutual attraction. However, the letters also recount their sexual dalliances with other men, in what appears to be a competitive attempt to make each other jealous.

‘I cannot understand…’

In a particularly telling line Geof talks openly about his frustrations of the law:

‘I cannot understand why it should be considered a criminal offence for two people of the same sex, who are fond of each other & mutually agreed, to commit sodomy.’ [MEPO 3/283]

Love letter to ‘Dear Earnest” from his ‘sincere chum’ Geof B Smith, typed up as evidence in a police file. Catalogue ref: MEPO 3/283

It would take a further 40 years for the State to partially decriminalise homosexual acts (find out more about the the passing of the 1967 Sexual Offences Act here). Essentially 22-year-old Ernie would have lived the majority of his life having to hide his sexuality from the law and wider society.

These letters now provide a remarkable and rare insight into LGBTQ+ lives in the 1920s; they tell a story of love, but also of criminalisation.

The consequences

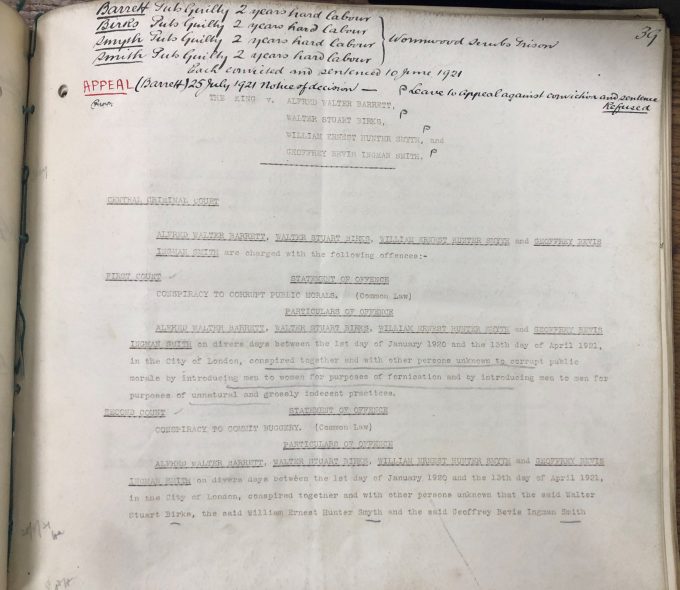

Ultimately Ernie and Geof were arrested, as well as the self-styled bohemian Walter Birks, who had also met men through The Link. In a particularly incriminating letter he had written, ‘All my love is for my own sex and I am very affectionate’. All three men were arrested under the charge of conspiring to commit ‘gross indecency’.

Indictments at the Central Criminal Court which commence criminal proceedings and set out the nature and date of the offence. 31 May 1921. Catalogue ref: CRIM 4/1435

One further individual was arrested – Walter Barrett, the proprietor of The Link himself, on the charge of aiding and abetting his advertisers, conspiring to enable the commission of such unnatural acts. All were tried at the Central Criminal Court, the Old Bailey.

At the trial Barrett himself claimed The Link was intended for decent people, and was used by decent people: ‘The other sort is not desired’. He admitted he had been careless – not realised people’s ‘true character’. Clearly the police saw differently…

Each was charged and received two years’ imprisonment with hard labour at Wormwood Scrubs.

Despite a successful life as an author and publisher, this proved to be Barrett’s downfall. The Link ceased to exist.

There is no clear evidence that Ernie and Geof ever met again.

What we can learn?

Despite the sad end to Ernie and Geof’s love affair, this case now tells us some extraordinary things:

- Despite the law a century ago, there were ways for LGBTQ+ people to meet. There were extraordinary underground networks that ran all over the country, which enabled queer people to meet

- That (unsurprisingly) LGBTQ+ love wasn’t London-centric or anchored to metropolitan areas. People wrote classified ads while based in Southsea, Liverpool, Birmingham, Portugal, London, Chelsea, Bristol, Bath, Canada, Cornwall, Lowestoft, Somerset, Mayfair, East Anglia…the list goes on!

- That people were able to develop their own coded ways of communicating, to circumvent criminalisation

- In spite of the significant risks, LGBTQ+ people continued to meet and defy the law

But it also leaves us with questions:

- How widespread was the knowledge of these underground networks and methods of communication?

- How many coded adverts actually led to people meeting through The Link?

- Were there other similar publications, now forgotten by history?

- And, unlike Ernie and Geof, how many people were able to meet through The Link and get away with it?

The Link, A Monthly Social Medium for Lonely People, No. 63. April 1921. Catalogue ref: MEPO 3/283

One hundred years on, people still instinctively crave ways to meet other people, whether it is through online dating apps or classified advertisements. The stories of people in The Link reflect themes that are still current and topical among the LGBTQ+ community: the need for queer spaces (physical and written), the loneliness and isolation that comes from a lack of social acceptance, and the instinctive desire to love and be loved.

In one particular letter Geof comments that ‘I think the “Link” and the U.C.C [thought to refer to the Universal Correspondence Club] are about the only ways I know about to become acquainted with people like ourselves’. What an extraordinary publication The Link was, enabling people to meet and love, despite the law.

Auntie Maureen will be helping to bring to life some of these coded, intriguing and sometimes naughty personal ads found in our collections.

‘Classified: A Performance of Queer Dating Ads‘ will take place on Saturday 23 November from 16:00 to 17:30 at the Royal Vauxhall Tavern.