‘Until other accommodation can be found the men are sleeping in the well-equipped shelter'[ref]‘Finding Jamaica Men Jobs’, Daily Herald, 24 June 1948, p. 3.[/ref]

Daily Herald

This quote, taken from the Daily Herald, refers to the temporary accommodation provided for 236 passengers who travelled on the Empire Windrush. Passengers disembarked at Tilbury Docks on 22 June 1948. In the same year, the British Nationality Act was passed, which created the status of ‘Citizens of the United Kingdom and Colonies’. This new legislation around citizenship aided post-war migration to Britain, as it gave people from British colonies the right to live and work in Britain.

Many of the 1,027 passengers on board the ship were able to organise accommodation prior to their arrival, especially if they had arranged to live with family or friends who had already migrated to Britain. However, this wasn’t possible for everyone. Those who had no onward address stayed in temporary accommodation at the Clapham South deep shelter in London, located underneath the tube station.

The Empire Windrush passenger list, one of The National Archives most iconic records, is an invaluable source as it contains a wealth of information about passengers – and their lives beyond the journey itself – all in one place. It records that just over 100 passengers listed their onwards address as ‘No address’, so it is likely that these passengers went on to stay at the shelter. Some passengers also had their accommodation fall through, so more people needed to use the shelter than was initially anticipated.

The National Archives holds numerous records on the Clapham South shelter which provide an insight into the stories of those who stayed there. However, it must be acknowledged that these records are largely official documents produced by government departments, and do not contain the voices and personal experiences of those who stayed at the shelter.

But why was Clapham South shelter chosen? What was it like to stay there? And where did migrants go after the shelter?

Why Clapham South shelter?

Prior to the arrival of the Empire Windrush, representatives from the Ministry of Health, Treasury, Colonial Office, Ministry of Labour and National Service, and the Assistance Board met to discuss arrangements for the reception of passengers onboard the Empire Windrush, as well as providing accommodation for those who were yet to find lodgings.[ref]Assistance Board Memorandum on ‘West Indian Workers’, AST 21/8, The National Archives.[/ref] It was decided that the Colonial Office would ask the War Office if accommodation could be provided at the deep shelter underneath Clapham South tube station, which they agreed to.[ref]Assistance Board Memorandum on ‘West Indian Workers’, AST 21/8, The National Archives. [/ref]

The Clapham South shelter was opened to the public in July 1944 and was used as an air-raid shelter during the Second World War.[ref]London Transport Museum, ‘Clapham South: Subterranean shelter’, https://www.ltmuseum.co.uk/clapham-south (accessed 8 March 2023).[/ref] Bunk beds and washing facilities were fitted in the underground passageways for civilians to use.[ref]BBC News, ‘Going underground: The Windrush arrivals’ subterranean dormitories’, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-44483090 (accessed 8 March 2023).[/ref]

Containing over a mile of underground passageways, the shelter was later used as a cheap hostel after the war and had capacity for more than 5,100 people.[ref] Meeting notes about ‘Jamaicans arriving on S.S “Empire Windrush” Docking at Tilbury at 7 a.m. on 22 June, 1948’, 21 June 1948, AST 21/8, The National Archives.[/ref] It is therefore likely that passengers from the Empire Windrush were not the only people staying at the shelter.

Special buses were put on for those travelling from Tilbury to the shelter.[ref]Meeting notes about ‘Jamaicans arriving on S.S “Empire Windrush” Docking at Tilbury at 7 a.m. on 22 June, 1948’, 21 June 1948, AST 21/8, The National Archives.[/ref] Whilst there were more than 300 women onboard the ship, as well as many children, our records suggest that only male passengers stayed at the shelter.

Staying at the shelter

On their arrival to Tilbury, passengers were greeted by Ivor Cummings, a Colonial Office representative, who was tasked with coordinating the reception of arrivals. In his welcome address, Cummings acknowledged that ‘conditions in the Shelter are far from ideal for a stay of more than 72 hours’, and great emphasis was placed on the accommodation being temporary.[ref]Short Address to West Indian Workers on H.M.T Windrush by I.G. Cummings’, CO 876/88, The National Archives.[/ref] A report produced by the Colonial Office shows that 236 migrants stayed at the shelter.[ref]Interim Progress Report on Empire Windrush West Indian Workers, 30 June 1948, LAB 26/218, The National Archives.[/ref]

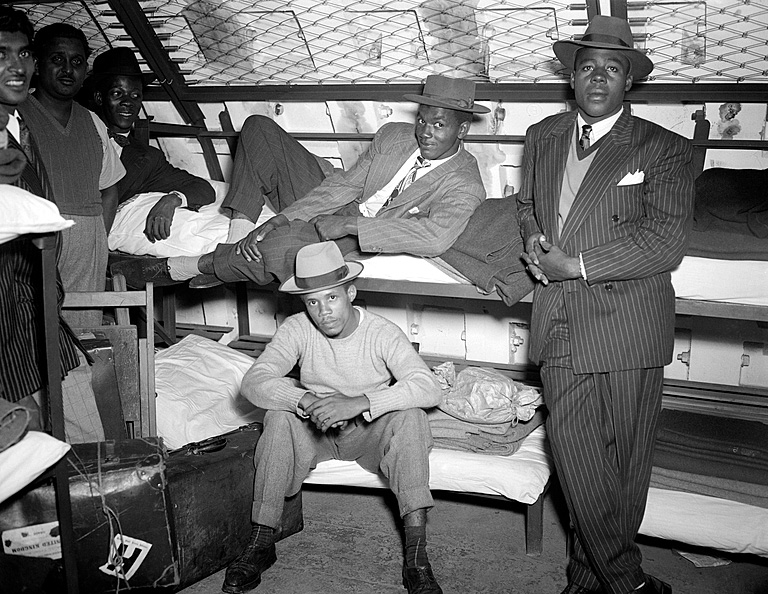

Life in the underground shelter was cramped and noisy. John Richards, a passenger on the Empire Windrush who stayed at the shelter, recalled how ‘The trains that ran overhead in the morning woke me up. There were beds all around with crisp white sheets.’[ref]BBC News, ‘Going underground: The Windrush arrivals’ subterranean dormitories’, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-44483090 (accessed 8 March 2023). [/ref] Richards is pictured on the far right of this picture.

Many migrants stayed in the shelter for longer than 72 hours. Rudolph (Nick) Collins stayed at the shelter for five days before he found a room to rent in Earls Court in London and started work at a factory.[ref]Windrush Foundation, ‘Nick Collins’, https://windrushfoundation.com/profiles/nick-collins/ (accessed 19 May 2023).[/ref]

Accommodation at the shelter had to be paid for and was not just the ‘benevolence’ of the state. Migrants paid 2 shillings a night for their board and meals, but support was offered to those who could not afford this. A canteen in the shelter also provided meals twice a day.[ref]Minutes written by Mr. Poynton, 3 July 1948, CO 876/88, The National Archives.[/ref]

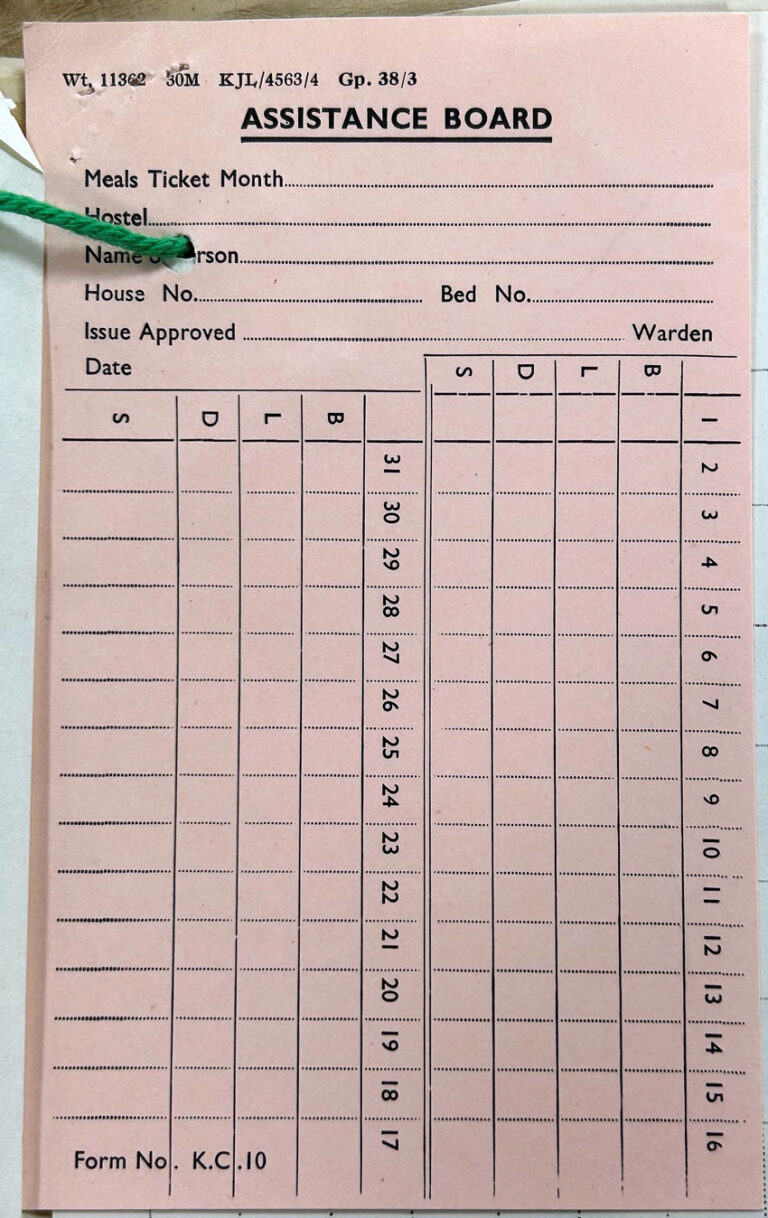

Those who were unable to pay for their meals were issued with meal tickets and a hole was punched through the appropriate square for every meal.[ref]Letter from J H Cottley to Mr. Bulleid of the Colonial Office, June 1948, AST 21/8, The National Archives.[/ref] The Western Morning News reported that the arrivals’ first meal was ‘roast beef, potatoes, vegetables, Yorkshire pudding, suet pudding with currants and custard, and tea’.[ref]‘Jamaicans Get Roast Beef’, Western Morning News, 23 June 1948, p. 3. [/ref]

Various social activities were organised for migrants staying in the shelter. The Mayor of Lambeth arranged a small party for 35 men on 23 June, which was followed by a cinema show. The Mayor of Wandsworth invited some of the men to take part in a cricket match, but this had to be cancelled due to bad weather.[ref]Interim Progress Report on Empire Windrush West Indian Workers, 30 June 1948, LAB 26/218, The National Archives.[/ref]

Welfare assistance was also provided at the shelter. Mr P.S Bulleid and Mr. Colin Bryan of the Colonial Office Welfare Department were on hand at the shelter to provide advice. It was also noted that Bryan was ‘a Jamaican social worker’.[ref]‘Short Address to West Indian Workers on H.M.T Windrush by I.G. Cummings’, CO 876/88, The National Archives.[/ref] This may have been a tactical decision by the Colonial Office as a way of presenting the ‘mother country’ in a more positive light, and migrants may have felt more comfortable seeking advice from Bryan.

A miniature employment exchange was established in the shelter, and much of the time was spent filling out paperwork and trying to find employment.[ref]Interim Progress Report on Empire Windrush West Indian Workers, 30 June 1948, LAB 26/218, The National Archives.[/ref] Arrivals were interviewed and registered by Ministry of Labour and National Service officials, who were then tasked with sourcing jobs for the men.

44-year-old Allan Brown from Jamacia was listed as a tailor on the passenger list and stayed at the shelter. Reflecting on his experience of the shelter, Brown told the Daily Herald ‘Everyone is very nice and working hard to get us settled’.[ref]‘Finding Jamaica Men Jobs’, Daily Herald, 24 June 1948, p. 3.[/ref]

Finding employment

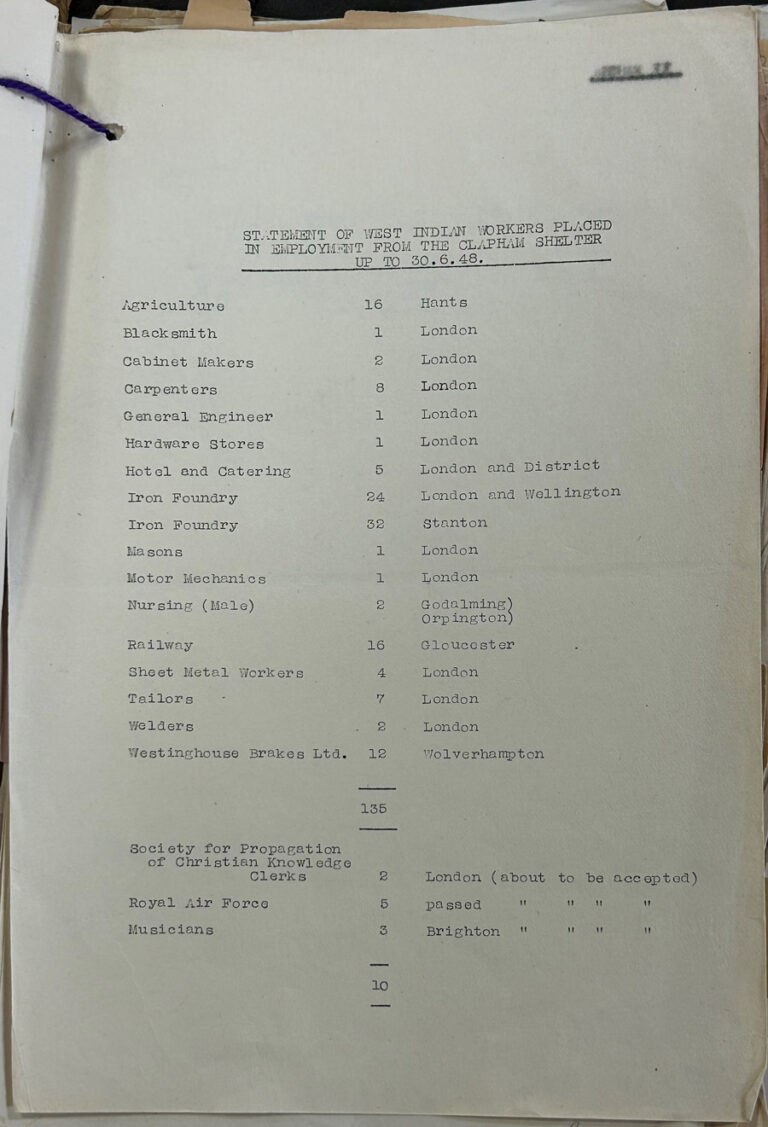

The men staying at the shelter went on to work in various jobs. A report produced by the Ministry of Labour and National Service shows the range of industries migrants were recruited into. As of 30 June, 16 men were working in agriculture in Hampshire, 32 in iron foundry in Stanton, 16 were employed by the railway in Gloucester, and 3 secured jobs as musicians in Brighton. These are just a few examples taken from this list.[ref]‘Statement of West Indian Workers placed in Employment from the Clapham Shelter up to 30.6.48’, LAB 26/218, The National Archives.[/ref]

Henry Raffington, aged 40 and from Jamacia, stayed at the shelter and was among those who went to work in Gloucester for the railway. Raffington’s occupation was listed as ‘mechanic’ on the passenger list and his proposed onward address was recorded as ‘no address’. The men set off from London Paddington to Gloucester with suitcases in hand for their new jobs, which entailed ‘loading and uploading wagons at a railway depot’. Raffington told a reporter that once he had earnt enough money, he planned to send for his seven-year-old daughter and also hoped to become a teacher.[ref]‘Henry, of Jamaica, gets railway job’, Daily Herald, 29 June 1948, p. 3.[/ref]

Another report discusses how a small number of the men went on to work for the tailoring department at the Salvation Army. The production manager praised the men’s work ethic and noted that ‘They were not used to our style of working – it’s purely tunic making; but they have adapted themselves and we are quite pleased.’[ref]Report produced by Eric Walrond, CO 876/88, The National Archives.[/ref]

It is also important to think about the political climate at the time. The government initially encouraged migration from its colonies and Commonwealth countries to boost the workforce after the Second World War. Responding to criticism about the arrival of migrants on the Empire Windrush, the Prime Minister Clement Attlee stated that ‘the majority of them [passengers] are honest workers, who can make a genuine contribution to our labour difficulties at the present time.’[ref]Letter from Clement Atlee, 5 July 1948, CO 876/88, The National Archives.[/ref]

The Clapham South shelter was vacated on 12 July, just under three weeks after the Empire Windrush docked in Tilbury. 17 men in the shelter had not yet found employment and were offered accommodation support from the London County Council.[ref]Final Report on Empire Windrush West Indian Workers, LAB 26/218, The National Archives.[/ref]

Many migrants from the Caribbean settled in Brixton, and the shelter’s close proximity to this area of London likely influenced this. Records held at The National Archives’ provide us with a greater understanding into the arrival and reception of passengers onboard the Empire Windrush, particularly those who stayed at the Clapham South shelter. However, it is important to recognise the limitations of these records and how they cannot provide us with information on migrants lived experience of staying there, or their experiences of living and working in Britain afterwards.

i there is no pics of the list and that is what i wanted

Thank you for comment. As this blog post focused on the Clapham South deep shelter, there are no pictures of the Empire Windrush passenger list. Digital images of the passenger list can be accessed via Ancestry. More information on this can be found in our Passengers research guide.

You can find a page on our education website in one of the lessons about migration. https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/bound-for-britain/