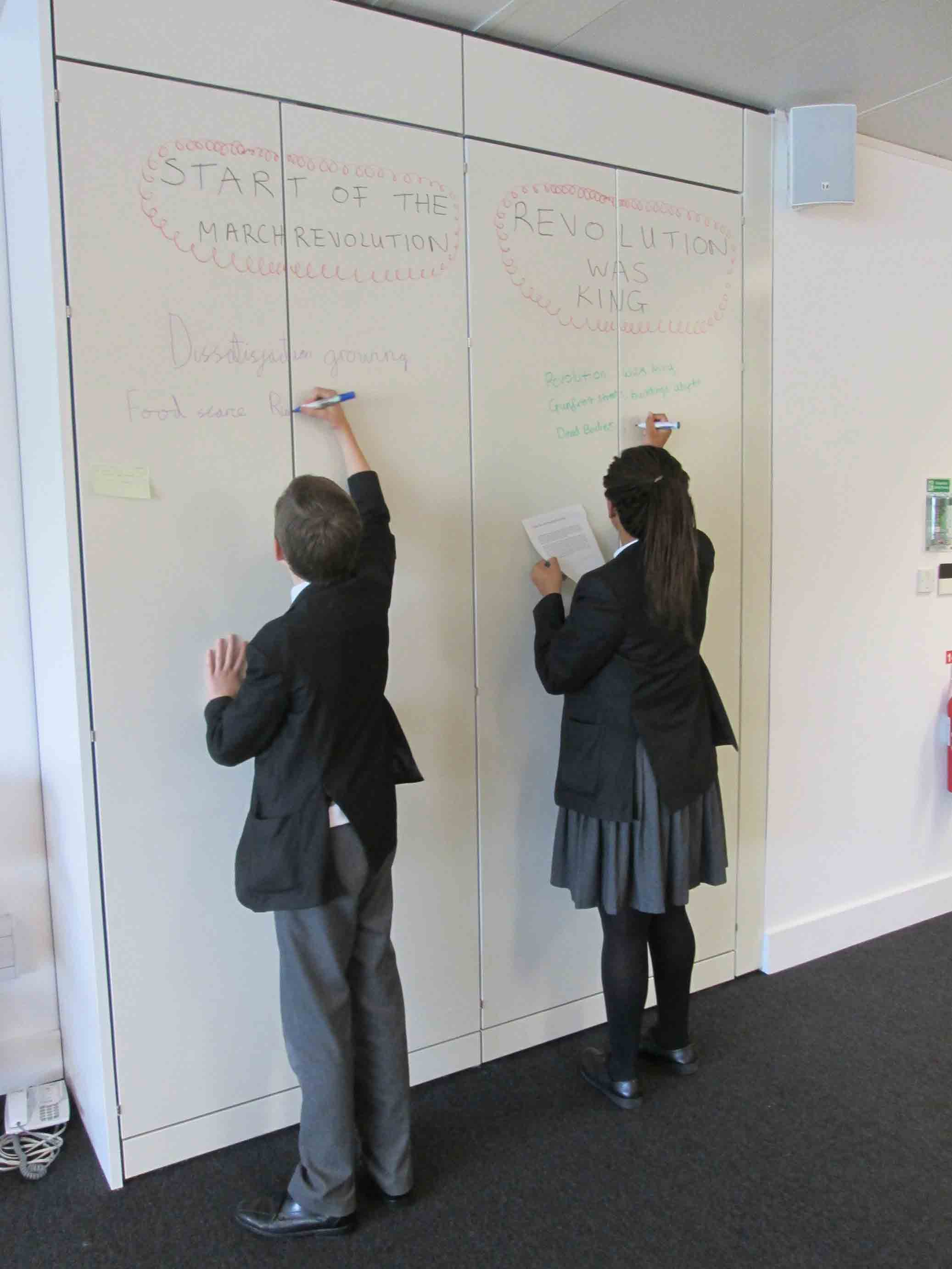

Students from the Wren Academy plan their dramatisation. Image courtesy of Wren Academy. Image courtesy of Sara Griffiths.

‘Revolution!’ It is 1917, and revolution stirs in Petrograd. Actually, it is a balmy Friday afternoon in September 2014 and we are in leafy Kew, where cries of students are sounding out through the corridors here at The National Archives. We are observing some of the events of Russia’s February revolution, as imagined by a group of drama and art students of The Wren Academy, from Barnet in north London, who have just participated in an education-led workshop.

The students, aged between 14 and 16, have never visited an archive before, and today their visit is a little different from that of most school groups passing through our doors. Firstly, they are not here as part of their history curriculum. They have come to learn about the Russian revolution and its context within the First World War. They are also exploring the motivations and actions of a British armoured car squadron, stationed in Petrograd to assist the Tsarist government, and especially those of Commander Oliver Locker-Lampson, its enigmatic and rather swashbuckling leader! The students’ workshop today will help inspire artwork and a piece of theatre which will be showcased at the Victoria and Albert museum (V&A), later this year.

This is a new outreach project, supported by the Friends of The National Archives and developed in conjunction with the V&A’s learning department and with students and teachers of Wren Academy. Part of our role in outreach is to use our collections imaginatively to inspire new audiences. A creative approach, working with artists and performers, allows us to engage groups from all walks of life, bringing new perspectives and interpretations on the histories we hold.

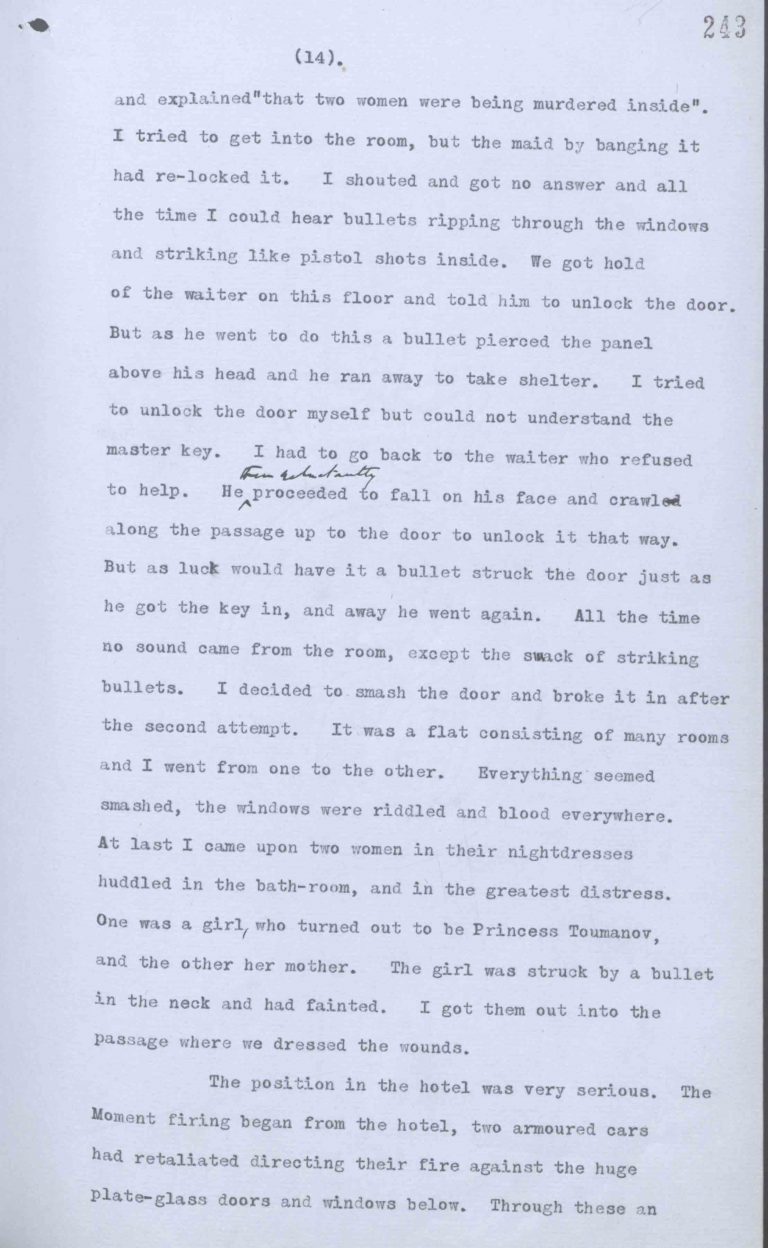

This project is inspired by a fascinating report that Commander Locker-Lampson wrote hurriedly to the Admiralty on 19 March 1917, held in one of our Foreign Office files (FO 371/2996). It is a description of events at the military Hotel Astoria in Petrograd. ‘Many were killed in the hall, and thoroughly roused, the revolutionaries mounted the stairs, the soldiers asking for revenge, the mob scenting loot in the carpeted corridors and luxurious flats of the hotel.’ During the course of that evening, the squadron rescue two women in fear of their lives, one of whom, Princess Eugenia Tumanishvili, has been shot in the neck.

These narrated events alone are exciting enough for dramatization, but there is a development of further interest beyond one historical account. Eugenia, aged about 18 at the time of rescue, later marries and flees Russia for Shanghai, giving birth on a train in Siberia. Her baby daughter, Tamara Toumanova, becomes at the age of 13 one of the ‘baby ballerinas’ or the ‘Black Pearl’ of the Ballets Russes. She enjoyed a career of well over 30 years after settling in the United States and being discovered by choreographer George Balanchine. Tamara danced in a number of films, including Alfred Hitchcock’s Torn curtain and with Gene Kelly in Invitation to the dance. After her death in 1996, she was buried in Los Angeles’ Hollywood Forever cemetery, alongside her mother.

Locker-Lampson’s report, catalogue reference: FO 371/2996

To return to our project, Locker-Lampson’s one historical account, surprising in the unusual informality of its language, has provided an important and exciting insight into the wide theatre of the First World War and some of the causes of the Russian revolution. It has fuelled the imaginations and creativity of a talented and enquiring group of young people, intrigued by the mysterious Rasputin, inspired by the deeds of the Armoured Car Squadron and the warrior-like Locker-Lampson. From this report at least, this squadron seems to embody ideals of courage, gallantry and leadership.

From here, the students are taking their research forward and, with the leadership of teachers from the Wren Academy, they are building their ideas into art and performance. This work will complement the V&A’s exhibition Russian avant-garde theatre: war, revolution and design 1913 – 1933. If you are interested in learning more about Tamara Toumanova, the V&A also holds a large collection of material relating to the ‘Ballet Russes’.

If you’d like to know more about this project, or other outreach projects that we run, email us at outreach@nationalarchives.gov.uk or write to us in the comments section below.

It actually was not the March Revolution but the ‘February Revolution’ taking place in March, just as the ‘October Revolution’ was by our calendar in November. This is a well-known fact and it is somewhat odd that no-one has noticed.

Hi David,

Thanks for your comment. We’ve made the change to ‘February revolution’ in the post.

Alexa

Hello!

Yesterday 07/02/2016 found your information on the events of 1917. This is very important information for me. It belongs to my grandmother’s brother Vladimir Khassidovitch. Father Tamara Tumanov.

Please let me know what is known about the people who lived in the Astoria Hotel, and details of the event

Vladimir

Hi Vladimir,

Unfortunately we’re unable to help with family history requests on the blog, but if you go to our contact us page: http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts via phone, email or live chat.

I hope that helps.

Nell

Please could you give me more details of any outreach volunteer jobs. Many thanks.

Linda

Hi Linda,

You can see all of our current volunteer opportunities here:

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/get-involved/current-opportunities.htm

Thanks,

Alexa

Hello.

I came upon this blog whilst doing some research of my own. My grandmother, Peggie Simms, was a nurse with the Scottish Women’s Hospital during WWI and stayed in Petrograd in July 1917 on the way down to the Romanian front. She kept a diary and wrote about having tea in the Hotel Astoria with a colleague and a couple of civilian English travellers – “Saw all the holes in their rooms where the bullets had found homes in the revolution. A princess had been killed in one of the rooms near.” Every now and then over the years I’ve had a go at finding an answer via the internet, so was delighted to find the above info this time around. This must be the same princess, though clearly she wasn’t killed! It’s very interesting also to learn who her daughter was.

Coincidentally, a couple of hours after this hotel tea, my grandmother found herself describing similar events to those that Locker-Lampson had witnessed – the beginning of the July Days – the Bolsheviks unsuccessful attempt to seize power that summer.

Thanks for helping me with my research. I hope the art and performance the students’ work led to went well.

Hugo

…I should clarify that the question I was trying to find an answer to was “Who was that princess?”!

Hi Hugo,

thank you so much for responding to the blog. I was fascinated to learn of your grandmother’s involvement in this history and I shall share your comments with the students and other project participants.

The performance and exhibition of artwork took place in December 2014 at the V&A Museum and the students’ artwork was exhibited at The National Archives last Spring. You might be interested in watching the summary videos on the process of creating the project, and on their performance and art displays via this follow up blog here; http://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/author/sgriffiths/

Thank you very much for sharing this information with us.

Sara

Vladimir Hasidovich captain went to the front, in 1916, sent from St. Petersburg to the front, 21 March 1916 of 39 avtopulemetnogo Borisov platoon under the 10th Army. The document provides the name Tumanov. The text Tumanishvili. Please let me know how to spell the name of the document.

Dear Vladimir

I was interested to learn of your family connection to the Tumanov’s. If you are happy to let me email you directly, I shall re-order the document and see if I can find out more information about the Tumanishvili/Tumanov name. From my recollection, other residents staying at the hotel were not mentioned as it was incidental to the events Locker-Lampson was recounting, but I am very happy to check.

Thank you for your enquiry,

Sara

26.XI.2016

Sara Griffiths,

I think you may find that the Princess TOUMANOVA is:

Prss. Nina Levanovna [1871-1951] (nee Prss. MELIKOVA) TOUMANOVA. Her yet to be married daughter:

Prss. Marie/Maia Georgievna [1892-1934] TOUMANOVA.

Husband of the first and father of the second: General of Cavalry Pr. Georgi Aleksandrovich [1856-1918] TOUMANOFF, Commander-in-Chief 6th. Cavalry Division.

Were this to be shown to be incorrect, I am always content to be corrected.

Georgi