These people are 'archivally intelligent'. Are you?

My inspiration for today’s blog post comes from three things that I’ve been involved with over the past few weeks.

The first was helping to teach on a training course run by the Institute of Public Rights of Way and Access Management about using archives. The second was taking part in our new ‘live chat’ service. Both of these set me thinking about the kinds of advice that I give people daily as part of my job. The third was that, alongside other members of the Cardigan Continuum reading group, I read an article by two American archivists, Elizabeth Yakel and Deborah Torres [ref] 1. Yakel, Elizabeth, and Deborah A Torres. ‘AI: Archival Intelligence and User Expertise’. American Archivist 66:1 (2003), pp 51-78. [/ref]. I found that this provided a useful structure for my thoughts.

Yakel and Torres explore what it means to be an expert user of archives and identify three distinct kinds of user-expertise, which they call subject knowledge, artifactual literacy and archival intelligence. In this post, I’ve interpreted these three in my own way.

1. Making sense of the topic: subject knowledge

Many expert users are very knowledgeable about the topics that they research. This doesn’t mean that they know everything about the subject (someone that knew ‘everything’ wouldn’t need to do research to find out more!) but most expert users have built up quite a lot of subject knowledge by doing research over many months, if not years.

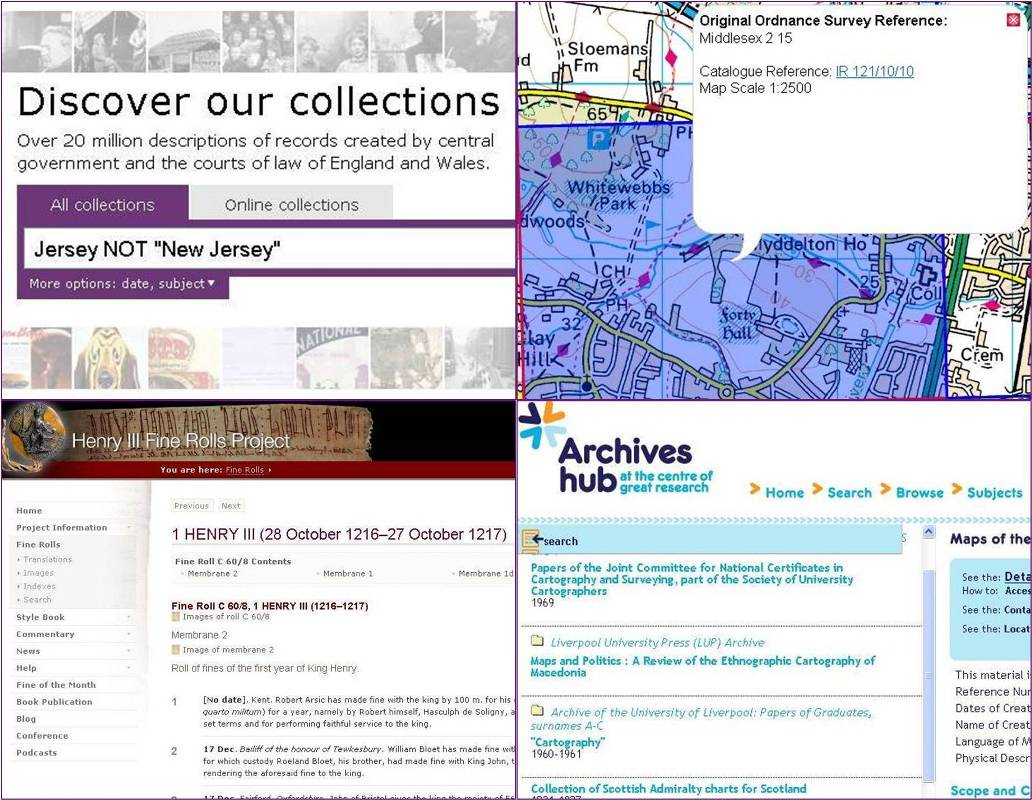

Some online finding aids. Clockwise from top left: Discovery (The National Archives' new catalogue), the Valuation Office map finder, the Archives Hub, the Fine Rolls of Henry III website

An expert user who wants to do some research outside of his or her usual field will normally do some background reading about the subject online or in a library first before delving into the archives.

2. Making sense of the record: artifactual literacy

Expert users are skilled at understanding the records when they are looking at them. Depending on the individual record and the research topic, this could include any of the following:

- Knowing how the record is structured and being able to pick out relevant information (for instance, people’s names) readily

- Palaeography skills: knowing how to read old handwriting

- Understanding the language, whether this means knowing some Latin, making sense of legal or technical jargon, or decoding abbreviations

- Specialist skills for particular types of record, such as map-reading

Expert users can also assess the relevance of individual records in the wider context of their research. Sometimes this means interpreting them with caution.

3. Making sense of the research environment: archival intelligence

- They understand archival concepts, such as provenance [ref] 2. ‘Provenance’ refers to where records have come from and how they were originally maintained and used. [/ref], and ‘speak the language’ of archives, using words such as series [ref] 3. A ‘series’ is what archivists call a defined set of records of the same type and the same origin. [/ref]

- They can use catalogues, indexes and other finding aids [ref] 4. A ‘finding aid’ is archivists’ jargon for any kind of index, list, catalogue or database that researchers use to identify records relevant to their research. [/ref] or search tools, both online and in paper form, to search for records. They can make the mental connections between their research topics, the finding aids and the records themselves

- They understand the referencing system and make cite references properly

- They prepare thoroughly and carefully for research trips

- If the research path is difficult or complicated, they can persevere and keep going

- Following the reading room rules is second nature to them

- When they visit different archives, or use different archives’ websites, they can pick up and adjust to variations in how things are done

- Above all, archivally intelligent users can form a research strategy and carry it through

Those of you who are still reading may wonder how researchers are supposed to acquire such as high level of archival intelligence. The answer – or part of the answer – is by experience. You wouldn’t expect to become an expert in, say, ballroom dancing without a lot of practice. Just like subject knowledge and artifactual literacy, archival intelligence is something that users of archives build up over time.

Some paper finding aids. Clockwise from top left: a 19th century handwritten index, some published calendars, a typescript list, a card catalogue

If you are relatively new to archives and want to get a head start in building up your archival intelligence, here are some handy hints to help you:

1. Watch some of our quick animated guides. These are designed to help new researchers approach their research in a more archivally intelligent way. Although some of their content is specific to using The National Archives, much of the advice is relevant to other archives too.

2. Next time you want to search an archive catalogue online – whether it’s our Discovery tool or another institution’s catalogue – take a look at the help text first.

3. Don’t be afraid to ask staff basic questions. It’s unlikely that you are the first (or the last) person to ask the same thing. (Although if your question is ‘May I eat a cupcake while leafing through this priceless medieval manuscript?’ [ref] 5. The answer is no, in case you were in any doubt. [/ref], please don’t be surprised if the response seems a little frosty.)

I’ve written previous blog posts on starting your research and planning a visit. If you have a question about another aspect of how you can become more archivally intelligent, please leave a comment below and I’ll try to cover it in a future post.

What next?

Some other archives’ websites include general guidance about using archives. Why not boost your archival intelligence by taking a look at a few of them?

I agree with all that you have said Andrew, contexts are important and do not assume that because something is written that it is correct, there are examples (eg National Land Fund history) where this has been proved to be less than accurate. Researchers should in my view not expect correspondence from Venice to be in English and that spelling may be wrong (and are in catalogues ‘as seen’ and words don’t have the same meanings.

Most archive offices are different and can take a little time to master their organisation of their records (e.g. very large and heavy Bishop’s Transcripts on the open shelves in Gloucester) and some don’t have internet access so looking through a census without an index takes you back to pre-computer days and a lot of time. Don’t expect that records like Magna Carta are not available on open display and to treat records with respect, they are unique and not leaqve them unbalanced on a shelf where they are likely to fall or someone else will put the lid on properly for you. And of course ask or look to see if the record is available or open and seasoned researchers know this.

Thank you, David. I like your use of the phrase ‘treat records with respect’.

I wonder whether we should think of respect for the records as a fourth facet of user expertise – something that’s distinct from archival intelligence, subject knowledge and artifactual literacy but develops alongside them.