The First World War represents a turning point in the history of war and medicine. For the first time in a major modern conflict, doctors were able not just to treat and save the lives of hundreds of thousands of sick and wounded military personnel, they managed also to make unprecedented numbers of injured and diseased soldiers fit enough to return to the front lines to fight again.

This was in part thanks to important developments in surgery and medical science – particularly advances in wound management, fracture treatment, nerve injury, bacteriology and immunology. But it was also the result of a gradual revolution in the organisation and administration of wartime medical care – something to which most governments and armed forces were by now giving a great deal of attention.

World War 1 doctor and nurses treating a wounded soldier (credit: Wellcome Collection)

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the bureaucratic systems of treatment developed by Britain’s Army Medical Services involved plenty of form filling and generated untold amounts of paperwork. Countless cards, certificates, case sheets and special reports were all produced and completed with a view to ensuring continuity of treatment. But they would also ultimately be used by Medical Boards and the Ministry of Pensions to determine a soldier’s discharge status, his degree of incapacity and the extent of pension he might be awarded.

Several types of these medical records survive in our collection today, within the record series War Office: First World War Representative Medical Records of Servicemen. Though they represent between just 3 and 5% of what was originally created (the rest having sadly been destroyed following the extraction of this sample), there are nonetheless 278 pretty hefty boxes included among the series, containing on average approximately 600 to 800 ‘medical sheets’ in each. And since September 2017, a small team of cataloguers, including myself, have been working hard to produce item level descriptions for the papers contained in a selection of these boxes.

Once completed, this work (funded by the Wellcome Trust) will mean that sophisticated keyword searches, drawing on the detailed content of the items contained in those boxes, will be enabled within our catalogue, Discovery.

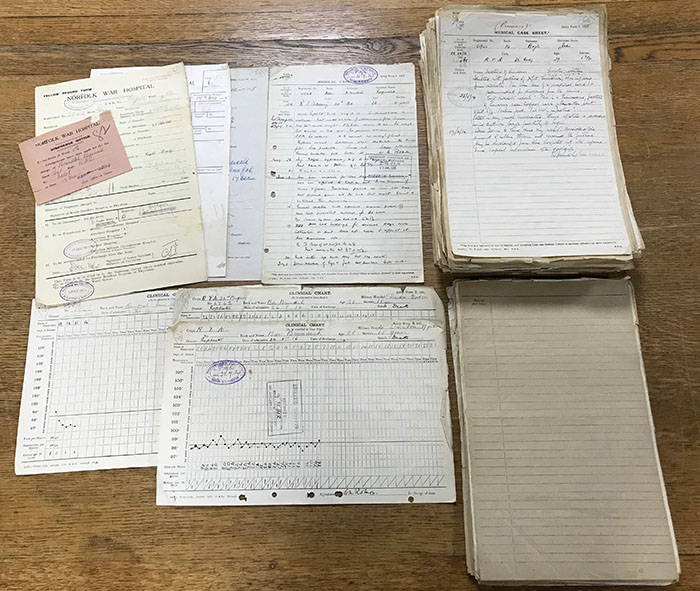

A selection of MH 106 documents

So what do these boxes of ‘medical sheets’ actually contain? Whether the box has been compiled as a representative sample of specific diseases contracted or injuries received – such as gunshot wounds to particular parts of the body, dysentery, frostbite and trench foot, gas poisoning etc., or as the selected experience of soldiers attached to particular regiments – such as the Leicestershire Regiment and the Royal Field Artillery, all are predominantly made up of hundreds of copies of ‘Army Form I. 1237’ – the Medical Case Sheet.

Each sheet typically documents a period of treatment for a sick or injured soldier who was admitted to hospital during the course of the war. They were very much living documents and were regularly updated by doctors throughout a soldier’s hospitalisation – even travelling with patients as they were transferred from one hospital to another.

You might expect that that they would be purely clinical in nature but they actually vary greatly in terms of content and detail – not to mention legibility – and can be accompanied by a host of additional documentation.

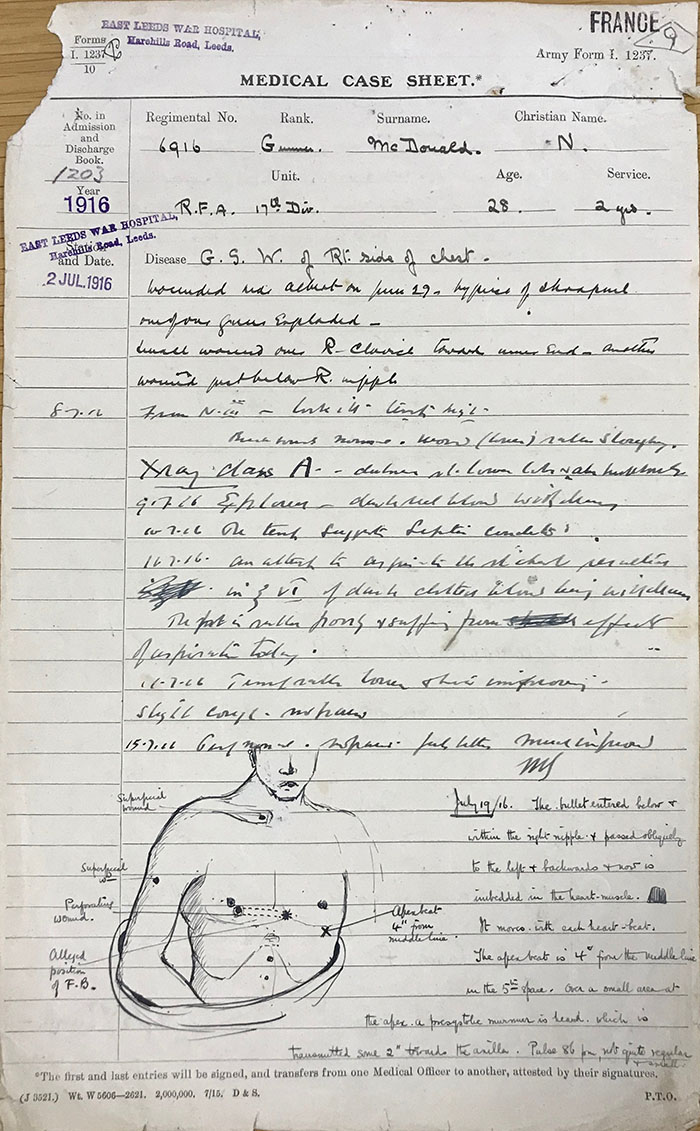

The case of Gunner Neil McDonald, Royal Field Artillery, spans 15 individual documents, including four medical case sheets, eight clinical charts and three lab reports (MH 106/2175/4). The first case sheet explains that he was evacuated home to the UK and admitted to East Leeds War Hospital on the 2 July 1916, having received a gunshot wound to the right side of the chest when one of the Artillery’s own guns exploded near Albert in the Somme region on 29 June.

It also contains some fairly graphic detail of the nature of his injuries: ‘The bullet entered below and within the right nipple and passed obliquely to the left, and backwards, and is now embedded in the heart muscle. It moves with each heart-beat’; and even contains a rather accomplished diagram of McDonald’s upper body, showing the situation of the perforating wound to his chest and certain other superficial wounds.

Medical case sheet for Gunner Neil McDonald, Royal Field Artillery: MH 106/2175/4

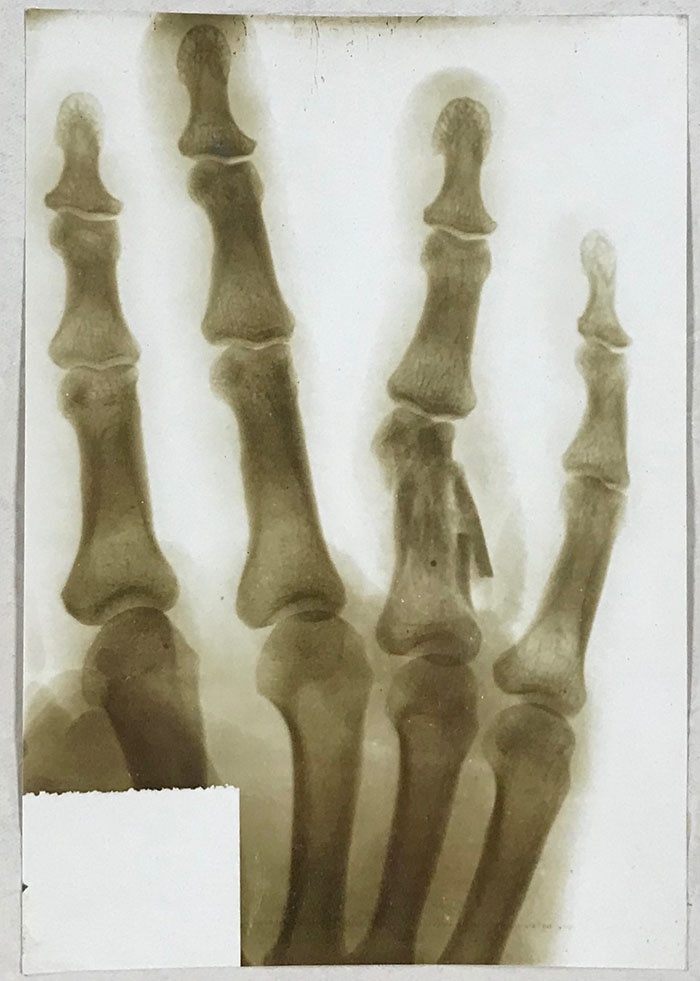

Some case sheets are accompanied by images of a different sort – X-rays. On 2 November 1916, Cadet Theophilus Talbot demonstrated that the risk of injury to military personnel was not reserved to those fighting at the front alone (MH 106/2175/39). He was admitted to New End Section Military Hospital in Hampstead with a crushed ring finger of the right hand – the result of an accident at St John’s Wood Barracks in which his hand became trapped between a gun and a wall. The X-ray which accompanies his medical case sheet clearly shows the fracture and severe swelling to his finger.

X-ray of cadet Theophilus Talbot’s injured right hand: MH 106/2175/39

Other cases paint vivid pictures simply through the words they contain. On 10 January 1917, 22-year-old Bombardier John Murray arrived at No. 21 Casualty Clearing Station at Corbie, France suffering with ‘nervous shock’ (MH 106/2175/74). Murray was able to explain to the doctors on his admission that on 22 October 1916 his Battery had been blown out of action at Flers, after which he had spent several weeks in hospital at Étaples. He re-joined his Unit on 5 January 1917, when his Battery was shelled once again – ‘I felt sick, giddy and powerless’, he is quoted as saying. He was admitted to the neurological section of No. 21 Casualty Clearing Station still feeling shaky, experiencing headaches and unable to remember what had happened after his Battery had been blown up for a second time.

Understanding of post-traumatic stress was still very much in its infancy at this time and approaches to its treatment often varied dramatically. Murray’s case sheets explain that he underwent a sort of hypnotherapy called ‘suggestion treatment’, and fascinatingly they contain a transcript of what Murray actually said during the sessions:

‘23/01/1917. Suggestion treatment given. It was suggested that he could see everything that happened to him over again. Pt [Patient] then shouted – “The gun’s gone” (Pt shows signs of fright). “Quick, hurry up and give us a hand. xxxxxxxxxxx Yes Mr Haynes, three are killed. Heron, Chittenden and Napper. xxxxxx “Look out” here’s another coming. Anybody hurt? xxxxx Tommy O’Brien killed and Bomb. McCleen wounded! xxxxxxx Yes Sir, yes Sir, Tommy O’Brien is killed Sir. xxxxx Clear away from the guns (Pt now shows signs of fear), they have got the range of us. xxxxx Look out, here’s another coming. Oh! The ammunition (Pt is now groaning). Oh my head. Oh it’s my head Mr Haynes. Is the Doctor coming? xxxxxx Where are you taking me Dicky? Hospital! Dressing Stn where? Xxxxxx Longueval! Xxxx On a bogie now xxxx I don’t remember any more.

‘Vigorous suggestions were then given that when he awakes he will remember everything.

‘27/01/1917. Pt was again given suggestion treatment. When asleep he was told he would remember what happened when he got to the Dressing Stn [Station]. Pt then said “They carried me into the Dressing Stn on a stretcher. The Doctor examines me and is going to give me an injection.” Pt shouts “Oh my arm.” “I then went to sleep. When I wakened up I had a sore head. They are now taking me away on a stretcher and put me into a motor ambulance. They put me on the top row. The car stops outside of a hospital. They now take me into a ward and I am put to bed. The Doctor sees me, but does not say anything to me. He is now talking to the Sister. Sister then gave me a drink of milk and she told me I was for evacuation to Base. I now put on a suit of pyjamas to go on the train with. I was lying on a stretcher in the train.”

‘Vigorous suggestions were then given that when he awakes he will remember everything that had happened to him since his Battery was blown up.

‘Pt’s memory is now quite normal.’

Murray arrived back in the UK in February 1917 and was admitted to the 1st Southern General Hospital in Birmingham. From there he was discharged to Woodcote Park Convalescent Hospital at Epsom on the 8 March 1917, but how he got on there is sadly not documented in these records.

You may have spotted that the case sheets of McDonald, Talbot and Murray are all taken from the same box of medical sheets – MH 106/2175. And there are plenty more interesting cases included within that box – from the young Private who offered himself for a blood transfusion and earned a brief period of respite from the war back home in the UK (MH 106/2175/192), to the unfortunate Corporal who was lying sick in hospital at Étaples receiving treatment for an old head injury when the hospital was suddenly bombed (MH 106/2175/107).

There are also many more different types of document to be found in the box – from a gassing case sheet completed at a Casualty Clearing Station in Watten, France (MH 106/2175/19), to a lab report showing a positive Wassermann test result for syphilis from Ras-El-Tin, Alexandria in Egypt (MH 106/2175/208); a medical transfer certificate filled in at St Andrews Hospital in Malta for a patient on his way back to the UK having reported sick on the Strumica Front with enteric fever (MH 106/2175/85), to the bespoke forms created for hospitals such as Addington Park War Hospital in Croydon (MH 106/2175/199) and Norfolk War Hospital in Norwich (MH 106/2175/16).

But that is not to say that this box is unique in its diversity of papers and the stories they tell. On the contrary, it is representative of the huge variety of cases and experiences which are documented throughout the series in general.

So far from being a collection of impenetrable clinical notes, these records are personal and engaging documents which place the individual soldier as a patient at the centre of their narrative, telling not only their stories but also the story of a medical profession striving to keep sick and wounded soldiers both alive and well, during one of the most unpredictable and destructive armed conflicts of all time.

You can already search more than 60 boxes of MH 106 medical sheets to item level in our catalogue, Discovery, with more boxes becoming available to search as the cataloguing work continues throughout the course of the year.

It would be nice if the catalogue had full descriptions (e.g MH 106/2116/12, where the information on hospitals will be released after 100 years it says), given it is dated 1915 and all of the men are now dead.

Thank you for your feedback. Improved descriptions for these records are being released in phases. The affected item had already been spotted for correction. The full description will appear in Discovery in due course. We are fully aware that some data is imperfect and are still working through the final checks and uploads. Please, bear with us until this catalogue enhancement work is completed.

My great Aunt was married to a WW1 soldier who was wounded in May 1918 and after the war he was discharged with a 40% disability pension. Sadly he died in 1931 aged only 30, but my Great Aunt did not receive a War Widows pension, despite her believing that his war injuries were in some part responsible for his death. In the early 1970’s she read an article about War Widows being unfairly deprived of the pension. With the help of the Royal British Legion she put in an appeal to receive it retrospectively. The Legion managed to access her husbands army medical records, (I have no idea where they had been stored or how they were located), including x rays of his injuries. His son kept the medical transcripts which have now passed to me. The record of his long journey to a partial recovery from gunshot injuries in French Flanders from the initial first aid post to Casualty Clearing Station on to Wimeraux hospital, Boulogne and then London before finally being sent to Becketts Park Hospital, Leeds, near to his home, in early 1920 for final rehabilitation. They give an insight in to how life changing battle field injuries took such a long (and painful) time to heal allowing even the beginning of getting back to a normal life. The records also help to create an awareness of how so many of those called up to serve their country went on to be affected by their war injuries for the rest of their lives. My Aunts husband is not recorded on any memorial but because of these preserved records I know so much about him and what he went through when he was only 18 years old, preventing him from being a completely forgotten casualty of war. They are a very precious and fascinating historical document to me. Sadly my Great Aunt never was awarded her pension as his “civillian” hospital records could not be located and his war injuries were not recorded on his death certificate, so were not linked to his cause of death!

My grandfather was ‘called up’ (?) on 2/11/15 (26 yrs, asylum attendant), posted on 5/3/16 as Gunner with Royal Garrison Artillery (presumed to France) but was discharged on 29/8/17 with “Disease- Indigestion”. Is it possible this might be a govt euphemism for the stomach aftereffects of gas poisoning? On 21/8/17 he was granted a pension of 27/6 weekly, with “Disability – Indigestion”.

He died (cause unknown to us) on 11/18/18, 3 days before the birth of his daughter, our mum. Any insight gratefully received.

These are incredible! I am part of a group of WW1 historical interpreters and one of our big interpretations is a Convalescent Hospital from 1918. In order to portray as a holistic impression as possible, I am gradually working on producing reproduction medical records which will then be populated per our characters in order to help tell their stories. Now that the world is gradually opening back up again, I definitely need to book myself a visit to Kew to look through these in person.

Trying to discover what some of the lettering on the hand written forms mean. My grandfather was injured just outside Arras in April 1917. A Service and Casualty Form shows ‘HA 8922’ and ‘HB’ & Fld? Hack’ . what do these letters & numbers mean?

This is all so fascinating! I am searching for my grandfather’s discharge papers with no luck so far. I have only found a medal certificate. We think he fought in the trenches for four years and then after the war he immigrated to Newfoundland (Canada) which was it’s own country at that time. Any suggestions on how to find his discharge records?

Dear Katie,

Thank you for your comment.

To ask questions relating to research, please use our live chat or online form.

We hope you might also find our research guides helpful.

My grandad was wounded in is leg and was on the hospital ship trailer 19/08/1915 John Thomas Cartwright 149th Field ambulance shame there no photos of him he later returned to the was I still don’t have photos.