What happened to petition fraudsters in the 19th century? Desperate women deserted by their sailor and soldier husbands often resorted to devious means to access their partners’ pensions as means of survival. Did their circumstances and their status as women allow them any compassionate leniency in the eyes of authorities? Would their community support them or cast them out?

Hidden within the extensive indexes of records series ADM 1 and MH15 lies the answer. Under the subheadings of ‘compassionate list’, ‘pensions’ and ‘relief in special cases’, there are hundreds of cases of appeals by women whose sailor and soldier husbands had deserted them without leaving any support. Petitions, the tradition of written ‘humble’ requests to an established authority, such as the King or Navy, pre-dated to the Middle Ages and presented a lifeline to these women by entitling them to request assistance and financial relief in return for faithful subservience.

However, demilitarisation following the Napoleonic wars, a population boom, and increased poverty meant the numbers requiring charity and relief outstripped resources. Petitions, therefore, were used by authorities to identify those who were most deserving. However, for those who petitioned falsely, imprisonment, blacklisting and hard labour awaited.

So why were fraudulent petitions from the deserted wives of soldiers and sailors so common?

These women had a precarious existence in the 19th century. Left on their own for several months or years at a time, their income and means of survival was often uncertain and reliant on their husbands’ generosity to share part of their wages while abroad. The Parish considered these women a long-term financial burden and were reluctant to offer them relief and instead focused their efforts on legally persecuting their husbands, although often without success. Adding to this pressure, the spectre of death loomed large for military men and many women faced an early widowhood.

In submitting petitions for pensions or relief, women came up against a hidden transcript of expectations. Relief and pensions were discretionary, not a right. Therefore, proof they were deserving was essential. Unspoken, but evident from the indexes which recorded outcomes, it is clear the Navy imposed harsh restrictions on re-marriage which meant women had to forfeit their pensions if they married again and did not remain a devoted widow. For both the Naval and Poor Law authorities, proof of good character and attempts at industrious modes of livelihood were essential criteria.

So, what was a woman to do?

My research into petitions has revealed that select women tried to overcome these exacting and narrow requirements through deceptive, deviant and dextrous means. These cases reveal the ‘humble petitions’ were not always quite what they seemed and were in fact part of an extensive investigative network.

Deceptive

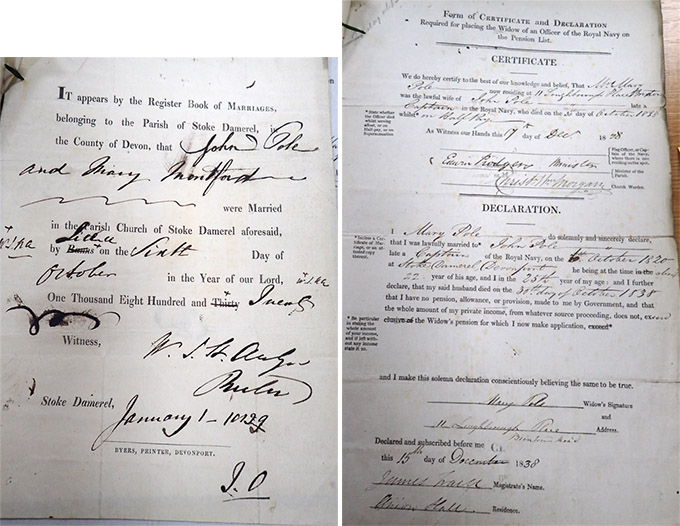

(Left) Marriage certificate of John Cole and Mary Montfort provided by the Parish. (Right) Forged marriage certificate of Mary Cole (Mary Touge, alias Pole) and John Cole identified by changed date. Catalogue ref: ADM 1/3724, 1839

A sleight of hand and subtle smudging of a marriage certificate was all it took to transform Mary Touge’s (alias Pole) petition into a 12-month prison sentence in the House of Correction. Investigation by a naval solicitor and cross-checking with church records and officials confirmed the clerk’s suspicion that the certificate was forged. Although there were often restrictions on age and length of marriage which could determine eligibility to receive a pension, Mary went one step further in twisting the truth. As well as altering dates on her certificate, she stole the identity of another woman, Mary Montford. Later letters within the file record her attempts to avoid questioning on account of sickness, but her deception was ultimately futile, as when she was brought to the Old Bailey she confessed and lost her liberty as well as her pension.

Mary Touge (alias Pole) was not unique in her deception, as five years earlier the Naval clerks uncovered a similar case of stolen identity. Instead of impersonating the dead, two women simultaneously claimed to be the widow of Samuel Reed and battled to prove their authenticity to access his pension. To find out more about this deceptive case you can use the ADM 12/300 subject digest under pensions to trace the investigation and outcome within the ADM 1 series.

Deviant

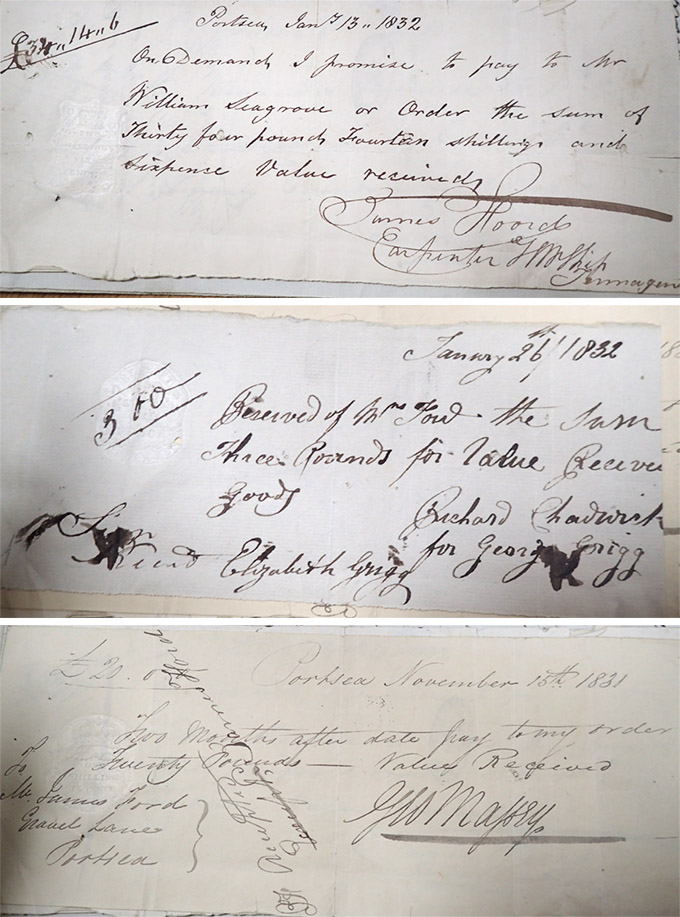

Selected debt receipts of Eliza Foord amounting to £100 and 1 shilling [est. £6,783 today]. Between 1831-1832 she accumulated debts four times the worth of her £25 per annum pension [est. £1,700 today]. Catalogue ref: ADM 1/4755, 1834

‘time after time she pawned and sold his clothes brought him twice into a Goal for her Debts she contracted for Drink was put in the work house by him and allowed a maintenance by him Broke from work house robbed her lodging got 7 months imprisonment in Portsmouth goal from that time living in adultery in London…’ (sic)

Catalogue ref: ADM 1/4612

This portrayal of Foord’s life makes her appear the antithesis of the idealised virtuous and meek housewife. The accusations of pawning and co-habiting suggest possible strategies for survival in a union often spent apart from her sailor husband. The Navy carried out its own investigation which confirmed through numerous receipts that Foord had a habit of spending beyond her means; indeed, in the period 1831 to 1832 the couple had spent £100 and 1 shilling (approximately £6,783 today). However, an account by the superintendent – while confirming her criminal record of ‘stealing a bolster’ – stated ‘it is thought she was given to this from the ill conduct of her husband who is reported to have been a worthless vagabond during his life time’.

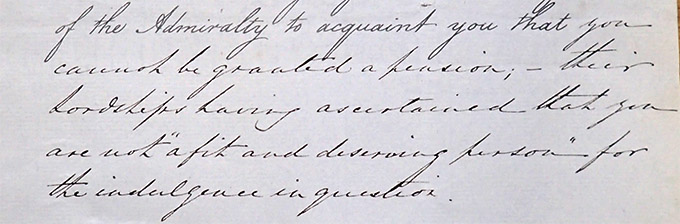

Despite the qualifications of Foord’s difficult relationship with her husband, the Navy did not show compassion and she consequently lost her substantial pension of £25 per annum (approximately £1,700 today) and was blacklisted as ‘not “a fit and deserving person”’. Her counter-petition requesting more information on why specifically she was deemed unworthy was ignored. Unfortunately, her perceived social deviance cast her out by her peers and caused her disappearance from the Navy’s charitable pension list.

Dextrous

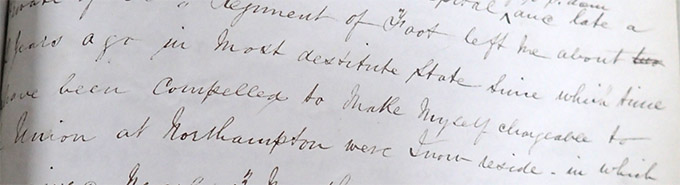

A handwritten petition by Catherine Scarborough, 1842. Catalogue ref: MH 12/8781. Further information

Similarly, Catherine Scarborough faced difficulties accessing her husband’s pension. Her husband resided in Chelsea hospital and had deserted her two years prior in what she describes as ‘a most distressed state.’ A serial petitioner, she applied several times unsuccessfully to the Poor Law authorities for relief and had spent time in the workhouse in the sick ward, stating she was trapped in a cycle of dependence, as she had to ‘relinquish two or three respectable situations’ as a servant due to her ‘very great deafness’.

Scarborough’s petition was successful in so far as it launched an enquiry from London into the local Union authorities. However, her dextrous strategy of using the workhouse as a temporary form of relief to avoid active employment was not well received. The New Poor Law expected people to be industrious and for the workhouse to act as a deterrent. It was Scarborough’s great misfortune that she was recorded by the master as saying ‘that whilst she was in the workhouse she said she did not come there to work but to get part of her Husband’s pension’, leading him to state that ‘her character was not good’. In addition, it was observed that she was an ‘abled bodied person aged 39 without a child’. There was no mention of her deafness, but it is clear that no additional leniency was given to her as a woman, particularly one without any dependents.

‘Not a fit object for your charity’

These women were criminalised and deemed ‘not a fit object for your charity.’ Although unsuccessful and carrying heavy penalties, these records are nonetheless valuable in highlighting harsh gendered expectations against those who were disadvantaged, either in providing for themselves without a core male breadwinner, or partnered to men prone to desertion or living a ‘vagabond’ existence.

The petition system was extensive in the 19th century, but the state put significant resources into investigating individual cases, which could result in harsh outcomes for those that had not lived a life that fit with the high moral standards of their superiors. These ‘humble’ petitions, which were found to be fraudulent, reveal part of a larger narrative of policy change in action which moved towards a less corrupt and discretionary relief system by the mid 1830s. Policing within the community also supported emphasis on fairness, character and industry, which together helped uncover not so humble strategies of petitioners.