‘Nicht schuldig.’ (Not guilty.)

These two German words pronounced somewhat defiantly, and almost flippantly, by 21 Nazi leaders, echoed through a very silent room of the Nuremberg Court on 21 November 1945, the second day of what the world would come to know as the Nuremberg Trials.

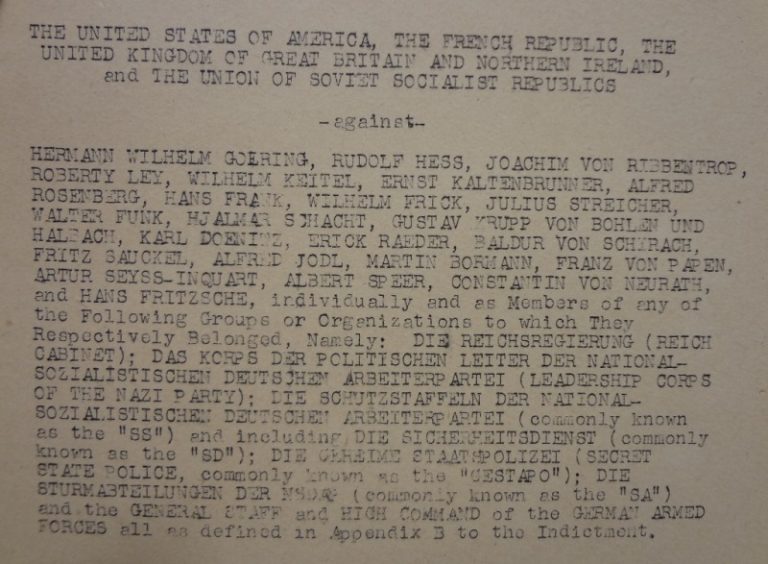

Establishing the International Military Tribunal had not been an easy task. The London Charter of 8 August 1945 (FO 93/1/266) had defined its principles and procedures but, in practice, it was a judicial nightmare. There was no precedent for such an international tribunal combining different legal traditions. These crimes were of such atrocity and on such a scale that they went beyond the scope of any existing legal system. How could they be judged? Who should be judged? Britain, France, the United States and the Soviet Union all had their own list. After difficult negotiations, they settled on 24 men (FO 371/51402).

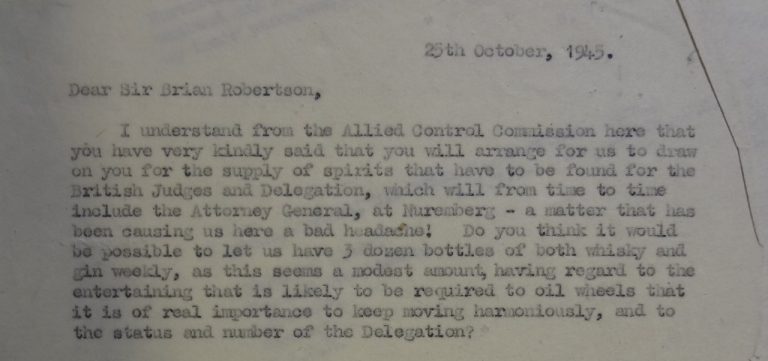

In the meantime, the British delegation was going through a crisis of its own. On 25 October 1945, Sinclair, the British prosecutor’s secretary, wrote to the Chief of Staff of the Control Commission to discuss ‘a matter that has been causing us here a bad headache’. Although the Court had been largely spared, Nuremberg was a ruined city and there was ‘no source of outside entertainment’. Yet the outcome of the negotiations also depended on the delegation’s capacity to display lavish hospitality. At the beginning of November, the prosecutor himself wrote to the Chancellor of the Exchequer, reiterating the request for ‘sufficient tobacco and liquor to smooth the way of these negotiations with our Allied colleagues’. In the end, spirits were provided by the Government Hospitality Fund, and Sinclair was able to write, just after the opening of the trials, that he was ‘hoping that soon a more frequent resort to the cup that cheers may serve to illume the sojourn of colleagues in a strange land’ (TS 26/171).

Letter from Sinclair to the Chief of Staff of the Control Commission (catalogue reference: TS 26/171)

All being well on the liquor front, and the Allies having come to an agreement, the trial could begin. There were only 21 men sitting in the dock, as Robert Ley had committed suicide in prison, Martin Bormann was never found, and Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach was deemed to ill to stand trial. They were:

- Hermann Goering (Hitler’s number two)

- Rudolf Hess (Hitler’s official successor until he flew to Scotland in 1941 to negotiate a separate peace)

- Joachim von Ribbentrop (Minister for Foreign Affairs)

- Wilhelm Keitel (Chief of the High Command of Armed Forces)

- Ernst Kaltenbrunner (Chief of the Security Police)

- Alfred Rosenberg (the party’s ideologist)

- Hans Frank (Governor of Poland)

- Wilhelm Frick (Protector of Bohemia and Moravia)

- Julius Streicher (Gauleiter of Franconia and ‘Jew-Baiter Number One’)

- Walter Funk (Minister of Finance)

- Hjalmar Schacht (former president of the Reichsbank)

- Karl Dönitz (Commander in Chief of the German Navy and Head of State from 1 May 1945)

- Erick Raeder (Admiral Inspector of the Navy)

- Baldur von Schirach (Head of the Hitler Youth)

- Fritz Sauckel (in charge of slave labour)

- Alfred Jodl (Chief of the Operation Staff of the High Command of Armed Forces)

- Franz von Papen (Ambassador to Turkey)

- Artur Seyss-Inquart (Reichskommissar for the Occupied Dutch Territories and Chancellor of Austria for two days)

- Albert Speer (Minister for Armament and Munitions)

- Konstantin von Neurath (former Minister for Foreign Affairs)

- Hans Fritzsche (Head of the Radio Division of the Ministry of Propaganda)

All these men had held senior positions and now stood before eight judges, two for each victorious nation, in what had been the Holy City of Nazism. The trial opened on 20 November 1945, presided over by British judge Lord Justice Lawrence, and was going to last four months and hold 403 open sessions in four languages (German, English, French and Russian) with simultaneous translation (FO 371/57435-57517). The defendants were indicted on four counts: ‘common plan or conspiracy to commit, or which involved the commission of Crimes against Peace, War Crimes, and Crimes against humanity’, Crimes against Peace, War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity – all of which had been defined by Article 6 of the London Charter.

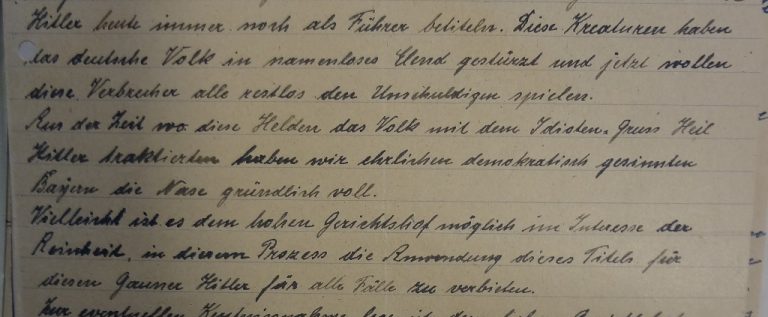

Robert Jackson, the chief American prosecutor, was afraid the trial might be hampered by lack of evidence. The judges and their staff, however, were absolutely swamped with evidence. Witnesses gave oral evidence, which had a substantial impact, and the Tribunal received thousands of letters from the German public, volunteering information and submitting pictures and press cuttings. One of them insisted that it should be forbidden to use the title ‘Führer’ when referring to Hitler (FO 1019/55).

He also included a picture showing the entrance of a Hitler Youth camp – the inscription reads: ‘We were born to die for Germany’ (FO 1019/55).

An anonymous sender provided photographs of excellent (technical) quality, with captions in strikingly poor German, depicting ‘the victims and work of destruction by the SS’. Most of them are extremely shocking, others merely highly unpleasant and disturbing. One shows a very pale, bespectacled, black-clad woman standing threateningly in front of a cupboard. The inscription above her reads ‘everyone in this room must act and speak courteously’ (although English doesn’t really do justice to the chilling tone of command of the German phrase), and the poster on the wall advertises rules for parents. The caption on the back of the photograph states: ‘I am not guilty’ (FO 1019/55).

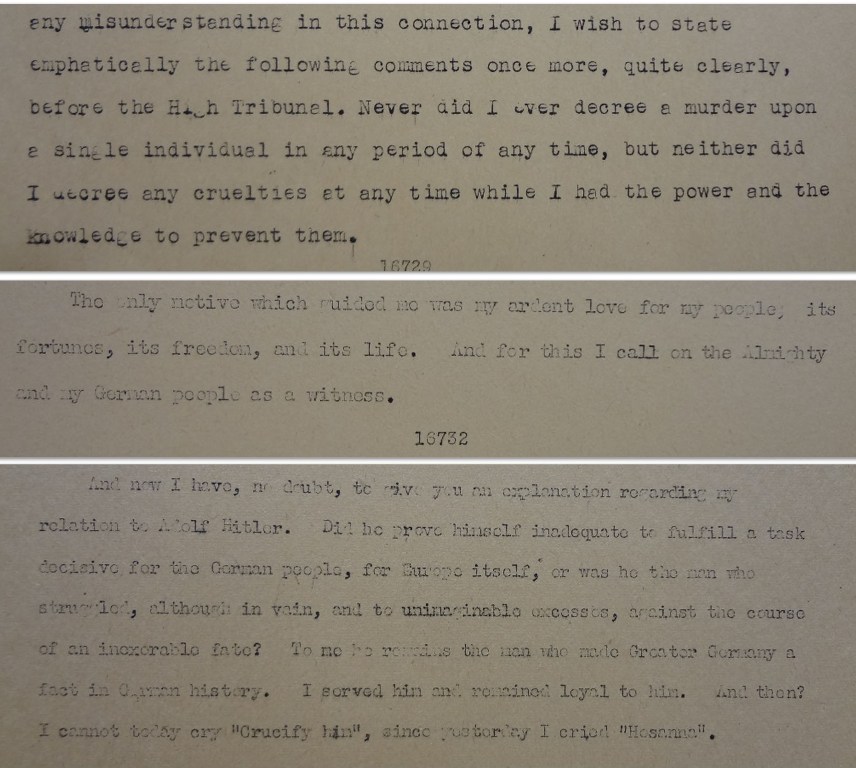

The final statements made by the defendants on 31 August 1946 show how dangerous these men still were, and how necessary a public trial was. Goering denied having anything to do with murder, Hess claimed to have acted out of his ‘ardent love for [his] people,’ and Seyss-Inquart reasserted his loyalty to Hitler (FO 371/57517).

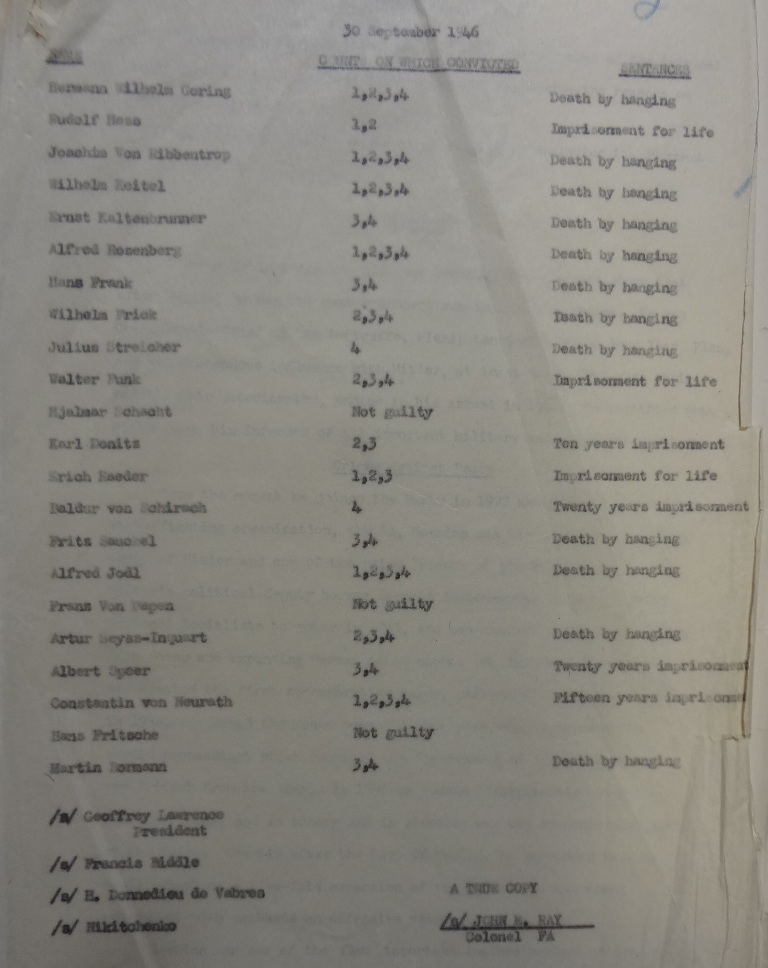

The sentences were finally read in the afternoon of 1 October 1946: ‘Defendant Hermann Wilhelm Goering, on the Counts of the Indictment on which you have been convicted, the International Military Tribunal sentences you to death by hanging’. The other sentences were:

- Rudolf Hess – imprisonment for life

- Joachim von Ribbentrop – death by hanging

- Wilhelm Keitel – death by hanging

- Ernst Kaltenbrunner – death by hanging

- Alfred Rosenberg – death by hanging

- Hans Frank – death by hanging

- Wilhelm Frick – death by hanging

- Julius Streicher – death by hanging

- Walter Funk – imprisonment for life

- Karl Doenitz – 10 years’ imprisonment

- Erick Raeder – imprisonment for life

- Baldur von Schirach – 20 years’ imprisonment

- Fritz Sauckel – death by hanging

- Alfred Jodl – death by hanging

- Artur Seyss-Inquart – death by hanging

- Albert Speer – 20 years’ imprisonment

- Konstantin von Neurath – 15 years’ imprisonment

Despite the ‘dissenting opinion’ of Soviet judge Nikitchenko regarding Schacht, von Papen and Fritzsche, the three of them were acquitted. Martin Bormann, judged in abstentia, was sentenced to death by hanging (FO 371/57517).

The executions of those defendants condemned to death were an additional problem. The Americans wanted to carry them out in Berlin, but it was deemed preferable to remain in Nuremberg for security reasons, but also because it was imperative that their bodies ‘shouldn’t become objects of cult at a later date’ (FO 945/346).

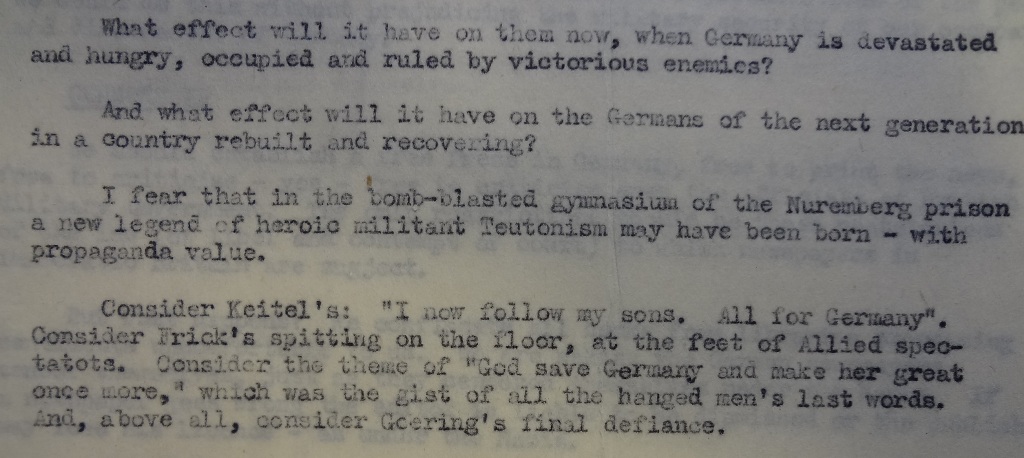

All were executed on 16 October 1946 in the gymnasium of the prison, except Goering who committed suicide in his prison cell the day before. The Daily Express correspondent reported from Nuremberg: ‘I fear that in the bomb-blasted gymanasium of the Nuremberg prison a new legend of heroic militant Teutonism may have been born’ and quoted their last words. ‘Consider,’ he wrote, ‘the theme of “God save Germany and make her great once more”, which was the gist of all the hanged men’s last words. And, above all, consider Goering’s final defiance’(TS 26/172). To prevent this legend from growing, the bodies were incinerated in Munich and the ashes scattered over the river Isar.

This trial which opened 70 years ago was only the first and best known of the Nuremberg Trials. It was followed by 12 others, lasting until December 1949. It was at the time, and still is today, criticised for being the ‘victors’ justice administered over the losers’ and its moral legitimacy had been questioned – some had pointed out that the Soviets had committed Crimes against Humanity at Katyn and Crimes against Peace when they had signed a non-aggression pact with Germany (FO 371/56474).

However imperfect the Tribunal may have been, it led to the definition of international law, and of the very new notion of crime against humanity. It established the principle of individual responsibility. It was a civilised alternative to mob justice. Germany, its former allies and its former enemies could take the first step on the long road to reconciliation and recovery.

Let’s finally remember some of Justice Jackson’s opening words:

‘The wrongs which we seek to condemn and punish have been so calculated, so malignant, and so devastating that civilisation cannot tolerate their being ignored because it cannot survive their being repeated.’

The Death sentence was warranted for the crimes they committed. The only trouble is they deserve much more than was performed.

Another very interesting post, especially as I am re-reading it in November 2020, some 75 years after the first Nuremberg trials started.

With this perspective it’s interesting to recall that Churchill was initially against any post-war trial feeling that the NSDAP leaders and others who had directed the German war effort should be executed out of hand, although I believe that this view changed as the trials went on.

Another interesting point is made in a recent (15 November 2020) article in the British newspaper ‘The Guardian’.

The paper quotes the views of one Holocaust survivor that (in his opinion) the trials were very ‘black and white’ with the Four Powers ‘seeking justice on behalf of the victims of the Nazis’ and yet each of the these nations were culpable in their treatment of the Jews – Britain and USA had strict quotas on Jewish immigration, anti-Semitism was ‘entrenched’ in the Soviet Union and France under the Vichy government ‘was proactive in deporting thousands’ of French Jews.

Which of course raises a number of interesting points.

While I (and I think many, many others) would undoubtedy agree with the points made in the article that the American, British, Vichy French and Soviet governments had discriminated against Jewish people in various ways, the trials were not simply about the murder of millions of individual Jews.

Other groups and individuals – from ranging from Slavs and other ‘non-Aryan’ groups to homosexuals to those who could be labelled as ‘handicapped’ to many who simply opposed the regime on moral grounds regardless of their ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation or political viewpoint – were also murdered although clearly not in the same systematic way.

Those accussed – at this and the subsequent Nuremberg Trials – had advanced the National Democratic Socialist Workers Party (NAZI paty) philosophy and had also carried out a variety of war crimes – Hermann Göring was cross-examined on the execution of fifty recaptured airmen who had escaped from Stalag Luft III POW camp during this first trial.

Other trials would focus more closely on these matters.

Moving away from the trials and what they were considering it’s almost laughable to think that with much of Britain, continental Europe, Russia, Asia, North Africa and the Middle East in economic and physical ruins the provision of ‘sufficient tobacco and liquor to smooth the way of these negotiations with our Allied colleagues should weigh so heavily on the minds of the British.

But then on reflection perhaps both my views expressed here, those I quote from a British newspaper and the others we all are free to have in a democratic society are only possible because of the outcome of the five-year long war.

Perhaps we should all be thankful goodness it ended the way it did.

What cruelty: Death by hanging.

While the death penalty has been long abolished in Britain(and most Western countries the United States excepted) in my view such a penalty was appropriate and proportionate for the individuals sentenced to such at Nuremberg. Indeed my reading of the trial history leads me to the conviction(even more now) that the trial was a fine example of justice delivered, given the unprecedented nature of the crimes laid before the tribunal. Perhaps Sauckel’s sentence may have been regarded as harsh(his superior was most fortunate to escape the gallows and the claim made by some historians that class distinction played a part may have more than a grain of truth!) However let us all pray that such a trial may never again be required anywhere….whatever atrocities have taken place throughout the world since then!

For what these Nazi monsters did – they were rightfully tried , convicted and hung at Nuremberg. The evidence was , indeed, overwhelming.

The suffering of the victims of the concentration camps was cruelty multipled 1000s of times! Considering how abominable the crimes were that were committed by these men, their punishment in comparison was rather mild. That said, I believe that their executions were drawn out deliberately. Death by hanging is instant. None of the Nazis were instantly killed. Some took upwards of 10 mins or more. John C. Woods is credited as being an incompetent hangman, but I’ve always suspected that he insured that the Nazis that he hung understood what it was like to suffer before they met their end.

I am replying to the comment by Das Richt Bosken Fri 26 Mar 2021 at 9:06 pm;

“What cruelty: Death by hanging”.

Our sages teach us that; “Whoever is merciful towards the cruel, will eventually be cruel towards the merciful”.

The Nazis and their collaborators put millions of people including infants, children, mothers, & the elderly to death, by unparalleled means that are much more cruel than hanging!!!

I got to visit the courthouse Room 600 in Nuremberg and it’s a very interesting place, very nice museum, full of history that cannot be forgotten! -TX

After reading Gina”s post above, I am confident she was right on point regarding John Wood’s intent. My father was one of the attendants on the scaffold. He retold his thoughts and concurred that Sgt.Woods sometimes intentionally would misplace the noose to insured the delayed death.

The sentence was death, not torture. Woods was out of line.

No death was cruel enough for these monsters. I had the privilege of attending a symposium at Vanderbilt University where the guest speakers were Holocaust survivors. I would find it hard to believe that anyone in attendance that day left there unchanged. When one speaker told the story of children being grabbed from their mothers arms and thrown against train cars, I emotionally lost it. Over 1 million Jewish children were killed by these monsters. And they didn’t do it by themselves, there were collaborators. I have read hundreds of books written by survivors. The best was Night. It’s raw and it is real, the thoughts of teenager experiencing things in a concentration camp that nobody should ever experience. My conclusion is I will never understand man’s inhumanity to man.

God bless all the Holocaust survivors, their families and their children.

Just to pick up on a turn of phrase from Rachel Livingston: “And they didn’t do it by themselves, there were collaborators.”

This is very often the way this observation is phrased, and, while accurate, I feel it lets the collaborators off the hook by implying a lack of agency. Those tried at Nürnberg not only didn’t “do it by themselves”, for the most part they didn’t do day-to-day atrocities, period. They facilitated, orchestrated, ordered, approved, demanded, yes, and they absolutely deserved their fate (or much worse). But the men who actually did it, did not – for the most part – stand trial at Nürnberg, they just disappeared back into the woodwork after the war, and went back to being “ordinary” people. Quiet monsters living invisibly among the sane and humane, untroubled by conscience or justice.

The kind of absolute evil represented by Nazism does not thrive in a vacuum. Every dictator is an opportunist, a symptom. Without popular support, they are nothing. It may be a minority supporting them, holding sway by terrorism, but it’s a bigger minority than we generally seem to care to believe. And they’re always there, waiting for their moment and their champion.