Seventy-five years ago today, the largest air and seaborne invasion force in history crossed the English Channel and successfully conducted an opposed landing on the beaches of Normandy, establishing a foothold in occupied France. An extraordinary feat of combined operations and logistics, this was the first step towards the liberation of the continent from the west, but also marked the beginning of nearly another year of bitter fighting that would take the Allied armies all the way to Berlin.

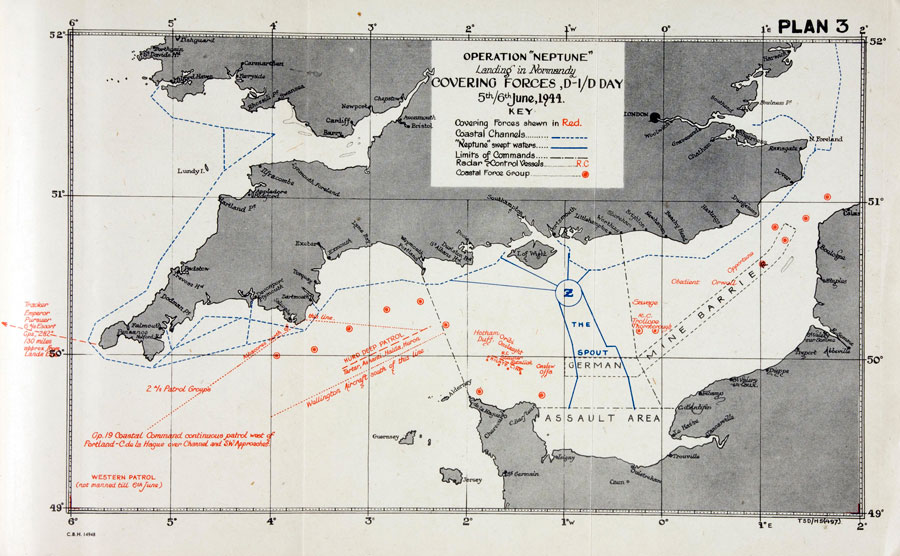

Map showing sea routes for Normandy landings (Operation Neptune), June 1944 (catalogue reference: ADM 234/366)

Preparation for the assault stretched back months and it was perhaps the most meticulously and intricately planned of all the Allied operations of the war, calling not only for seamless collaboration between all branches of the armed forces but also between a coalition of nations. Originally scheduled to take place on 5 June, inclement weather the day before led to a 24-hour postponement, forcing some of the assaulting forces already at sea to turn back. Facing a brief window of calmer seas and workable tides over the next two days or a much lengthier delay, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Forces, General Dwight D Eisenhower, gave the go ahead for Operation Neptune at dawn on 5 June. This was the assault phase of Operation Overlord, the code name of the wider invasion of occupied north-west Europe.

British LCTs (Landing Craft, Tank) approach Sword Beach, 6 June 1944 (catalogue reference: DEFE 2/419)

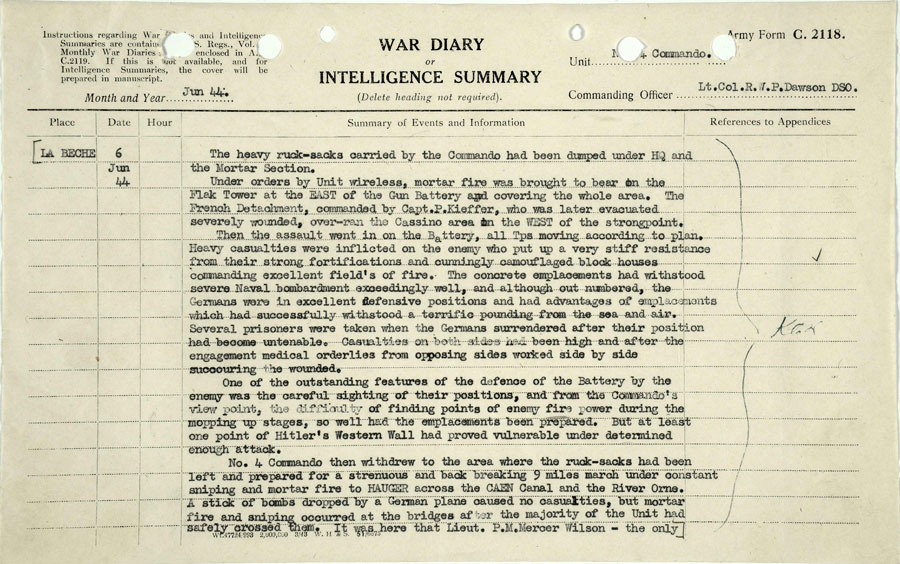

What happened next was as much an organisational and logistical exercise as it was a battle. By the time the seaborne forces were underway and navigating the channels carefully swept for mines, airborne units were already on the ground – the first having landed in gliders shortly after midnight to capture the Caen Canal and River Orne crossings to secure the British left flank. The naval forces that left ports along the English coast on 5 June arrived off the French coast in the early hours of the next morning. With the naval bombardment beginning shortly before 05:30, the assaulting infantry took to their landing craft in the deafening noise, and specialist tanks – amphibious and able to proceed to the beaches under their own power – were released in support.

Map showing fighter patrols in the assault area and over the main shipping routes during Operation Neptune (catalogue reference: MPI 1/450/1)

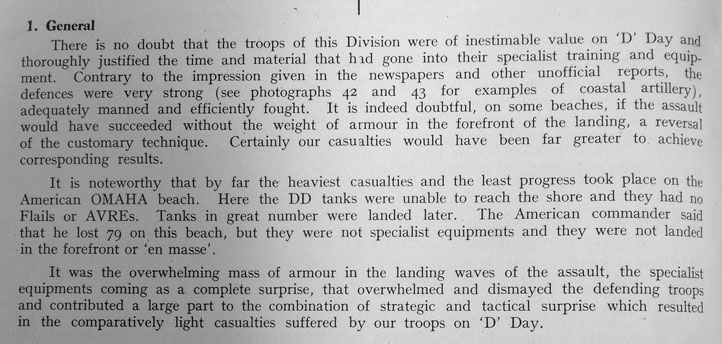

On Gold, Juno and Sword – the British and Canadian beaches – opposition was overcome relatively swiftly, in part thanks to the availability of armoured support as the infantry landed, which helped to neutralise strong points and clear obstacles from the beaches. Similarly, and despite some navigational issues, on Utah the Americans overran the defences relatively quickly and established themselves inland. Only on the other American beach, Omaha, was the full horror of a ferociously opposed landing realised, in part due to the nature of the geography and surviving defences, in part due to the lack of armoured support for the first waves. Though costly, bloody and nearly ending in disaster, even here the story was one of success come the end of the day.

Sherman DD (‘Duplex Drive’) amphibious tank. 79th Armoured Division Final Report (catalogue reference: WO 205/1159)

Reflections on the performance of specialised tanks on D-Day. 79th Armoured Division Final Report (catalogue reference: WO 205/1159)

Within five days of 6 June, the Allied bridgehead was 50 miles wide and 12 miles deep. Though later analysis would show that the Allied armies landed fewer men and materials than they had hoped, they had nonetheless orchestrated an extremely complex and effective invasion of a fortified landing ground. As well as extensive deception operations, this had involved an aerial and seaborne bombardment, the seizure of key points inland by airborne forces, the shipping and construction of temporary harbours and, of course, an opposed landing by infantry and armour on the beaches themselves. It was, without question, a tremendous success.

Photograph demonstrating the effectiveness of the Mulberry harbours in rough seas. (catalogue reference: DEFE 2/499)

The landings of 6 June 1944 were not unique to the war. Similar operations had taken place in 1942 with the abortive Dieppe Raid and the much more successful invasion of French North Africa in Operation Torch in November. Further successful landings took place in Sicily and Italy the following summer, as Allied forces pushed the enemy back from its more distant strongholds. It is the Normandy landings, however, that capture the popular imagination, largely thanks to the fact they have been immortalised in film, but also because of their scale and perceived significance to victory. Though unquestionably momentous, victory on the beaches did not precipitate a collapse of the German forces in France, and the fighting that followed was hard and victory in Europe was not realised for almost another year. At least for the Western Allies, however, 6 June marked the beginning of the end of the war.

Given the scale and complexity of these operations, it is impossible to condense meaningfully the finer points of the D-Day landings into a single blog, let alone tell the hundreds-of-thousands of individual tales of those who fought through it. As the official archive of the British armed forces, however, The National Archives holds the largest collection of unique contemporary records that tell the story of the British campaign and what came afterwards.

Whether you have obtained a relative’s service records from the Ministry of Defence (most personnel records from after the 1920s have not yet been transferred to The National Archives) or you have a particular interest in an aspect of the campaign, you will find records held by The National Archives that document these events.

Our general guide to researching British government and military records of the Second World War is a good place to start, but the following in-depth guides explain how to find the operational records of the Royal Navy, the army and the Royal Air Force:

- Royal Navy operations

- British Army operations (particularly unit war diaries in WO 171)

- British Army casualty lists (WO 417)

- Royal Air Force operations (particularly combat reports and operations record books)

- Military maps of the Second World War

Notes:

The term ‘Great Crusade’ is extracted from an order issued by General Dwight D Eisenhower ahead of the D-Day landings. It can be viewed online on the website of the US National Archives and Records Administration.

We should not forget PLUTO (Pipeline Under the Ocean) which supplied the fuel for the armoured vehicles and as Mountbatten once said that the Mulberry Harbours were viewed as a crazy idea the fact is that they survived the following storms and were a totally vital part of the operation.

An interesting post that shows that Operation NEPTUNE and ultimately OVERLORD succeeded through technological innovation as well as weight of numbers and (inevitability) luck.

I was particularly interested to find out what a Fighter Detection Tender (three are shown on the Fighter Patrol Area map) was.

Luckily for me a post on the RAF Museum’s blog describes not just what they were – what might now be described as radar pickets, that is forward radar stations designed to protect the invasion fleet – but also some of the lesser known aspects of air support given to Operation NEPTUNE.

The post (Lawn mowing on D-Day) can be found at https://www.rafmuseum.org.uk/blog/lawn-mowing-on-d-day/

Operation Neptune relied heavily on the work of the Combined Operations Pilotage Parties – a highly secretive commando unit made up of navigators and hydrographers from the Navy, along with Royal Engineers, who normally had Commando or SBS training.

While the SBS – who carry out the modern day role – was already in existence, COPP’s reconnaissance teams trained at Hayling Island Sailing Club from early 1943 onwards took on the vital work to survey the proposed invasion beaches in Normandy to ensure as many men, with as much equipment as possible, could get ashore without the risk of another Gallipoli.

They undertook four extensive surveys covering Juno, Sword, Gold for British and Canadian forces, and Omaha for the US – the most famous at Ver-sur-Mere on New Year’s Eve in 1943, to test for peat bogs covered by sand which could not bear the weight of armoured divisions coming ashore.

The date was chosen after it was thought the German guards would be too busy seeing in the New Year to notice a couple of shadowy figures emerging from the surf having swum ashore from a landing craft, crawling through the shallows taking gradients, samples and making drawings of the beach, its fortification and likely exit points.

Other missions relied on canoes which were either transported by MGBs based at Haslar in Gosport, or an X-craft submarine from nearby Fort Blockhouse (HMS Dolphin).

COPP’s existence was covered up by the 30-year rule although fictionalised accounts of certain events emerged in the 1950s. They swam naked in Chichester Harbour in the depths of winter to prepare for the cold, and could only wear clumsy protective kit to fight the cold on operations.

Their story was only eventually told in Stealthily by Night by Ian Trenowden (published in 1995), using the COPP’s wartime records from the old Public Records Office at Kew and HM Stationary Office.

The official training manual stored there gives a huge insight into the working of COPP.

While the unit’s service record is by no means complete, there is a treasure trove of wartime secrets that Ian sifted through to tell the remarkable tale of 215 men who surveyed the enemy beaches in Europe (as well as the river crossings of the Elbe and Rhine), North Africa, Italy, Sicily, Rhodes, Burma, Sumatra, Thailand and Malaya.

The Allies finally landed unopposed in the latter on September 9, 1945 during Operation Zipper, the last official action of WWII by UK forces and a COPP unit – there were 10 operational around the world by the end of the war.

Churchill – through Combined Operations chief Lord Mountbatten, who gave the order to create COPP in December 1942 and personally oversaw much of its vital work before heading to the Far East – and Eisenhower all came to rely heavily on the brave COPP heroes… who received 90 medals for gallantry between them.

A war memorial was finally built on Hayling seafront, with the help of Prince Charlies, in 2012. Sadly, only one of the COPPists – Jim Booth – is still with us – 10 lived long enough to see the memorial completed in honouor of the foresight of the unit’s founder and father – Captain Nigel Clogstoun Willmott, DSO, DSC*, RN, who died in Cyprus, on June 26, 1992.