As we approach the coronation of King Charles III, what better time to delve into our library to learn about a previous celebration of a monarch being crowned?

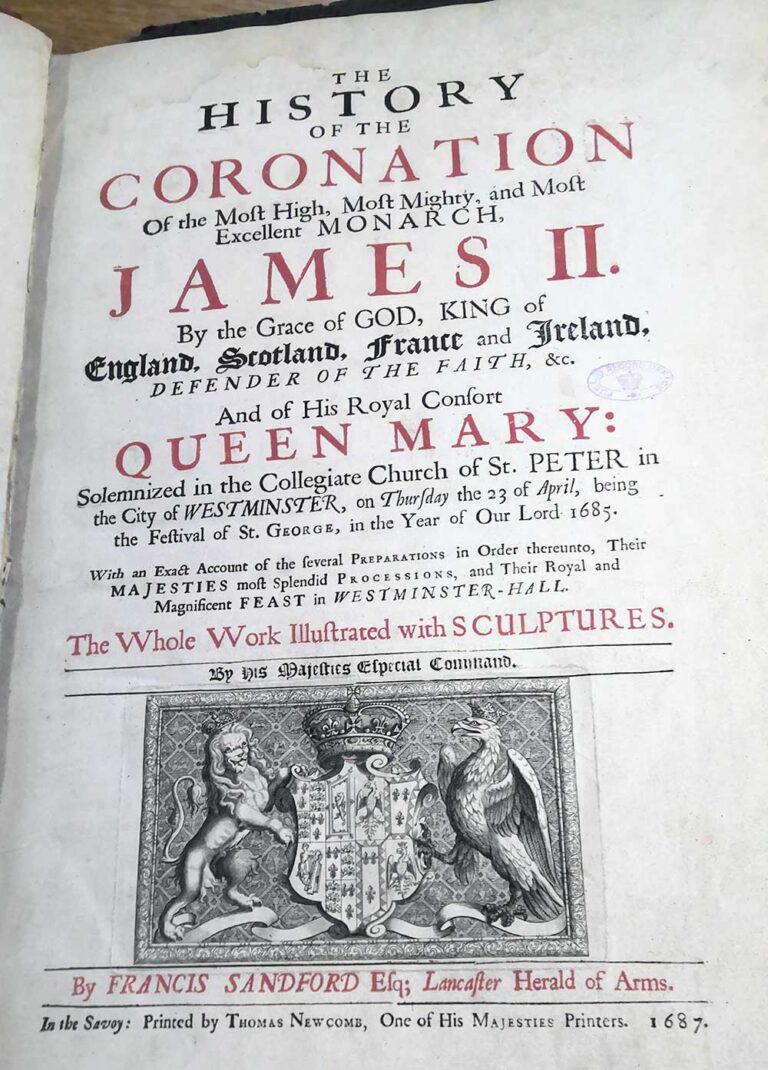

The coronation of James II was held on 23 April 1685, a lavish occasion recorded by Francis Sandford (1630–1694) in his book ‘The history of the coronation of the most high, most mighty and most excellent monarch, James II’. This book is one of about 300 17th-century publications in the rare books collection held in the library at The National Archives.

It took two years for Sandford to complete this sumptuous book — possibly as lavish as the coronation itself — a truly monumental souvenir. It is a detailed account of the coronation for James II and his wife Mary of Modena and features 27 finely engraved images as well as headpieces, initials, and line drawings by several engravers.

Francis Sandford wrote not just about the coronation itself but also detailed descriptions of the preparations, clothes, crown jewels and regalia and all the people that took part in the processions. He also described the ceremonies, feast and fireworks that constituted the coronation and subsequent celebrations. He was assisted in its production by his fellow herald, Gregory King (1648–1712).

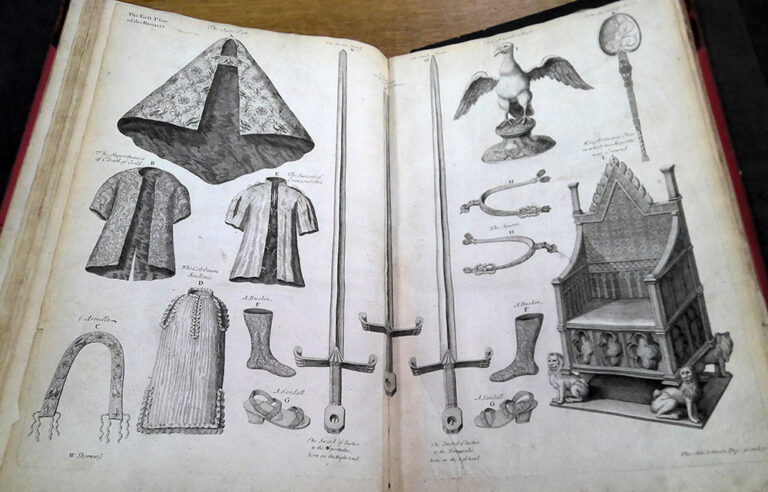

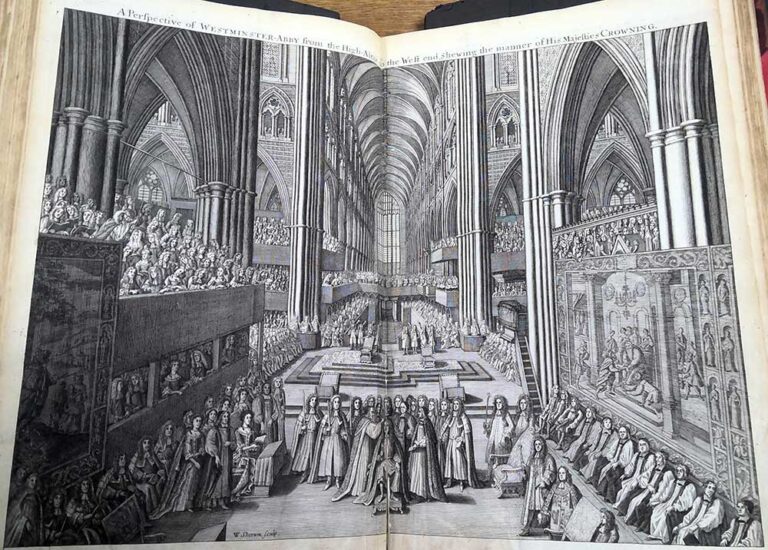

One of the reasons it took Sandford so long to get his book printed was the need to wait for all the fine engraved plates he commissioned to be produced. The plates show the regalia, procession, coronation, banquet, and fireworks. They also include plans of Westminster Abbey and Westminster Hall.

Engravers and illustrators are frequently unacknowledged in printed works, but it is always worth looking carefully at images to see if you can spot a signature. In the case of the ‘History of the Coronation…’ a small number of the illustrations are signed and so we can identify at least five engravers were commissioned by Sandford: James Collins, Samuel Moore, William Sherwin, John Sturt, and Nicholas Yeates.

Four of the engraved plates are signed by William Sherwin (1645–1709). He experimented with a variety of different media and is credited with the early invention of a method of mezzotinting. Historians believe Sherwin was possibly the first master printer of calico, after being awarded a patent in 1676 for ‘Printing broad Calico and Scots clot with a double necked rolling press’. Sherwin was based in West Ham, Essex which became one of the chief centres for calico printing in England.

Sherwin’s two plates of engravings of the regalia used at the coronation are placed close to the descriptions provided by Sandford. The first plate of the regalia includes images of items of clothing and footwear used at the King’s investiture, and Sandford provides a highly detailed description of each item, such as this for the sandals:

The sandals were made with a dark-colour’d leather sole, and a wooden heal covered with red leather, the straps or bands, whereof two went over the foot, and the third behind the heel, were of cloth of tissue, lined with crimson taffeta, as was also the bottom r inside of the sole: the whole length of the sandal was 10 inches.

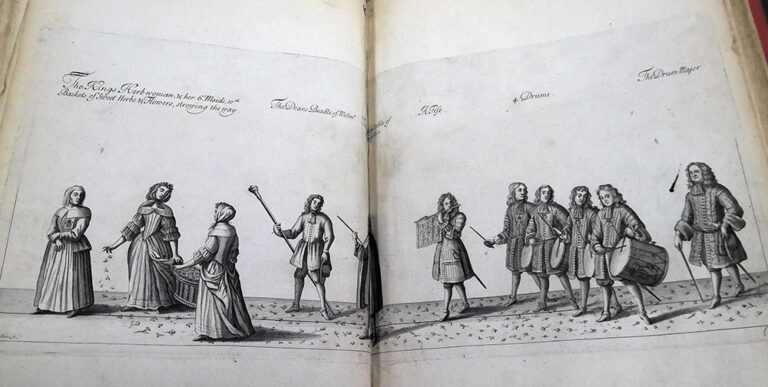

Sandford’s description of the procession from Westminster Hall to Westminster Abbey includes the number of people of each rank or profession, their names and what they were wearing and carrying. There were 19 engraved plates to illustrate the procession, although unfortunately, a few of these are missing from our copy. The procession was led by the Dean’s Beadle of Westminster, William Wells, who was preceded by the King’s herbswoman and her maids strewing flowers along the route, as illustrated in the first plate in the series.

Sandford himself participated in the procession as he was Richmond Herald — one of the Officers of Arms who acted as staff to the Earl Marshal who was responsible for organising the coronation ceremony.

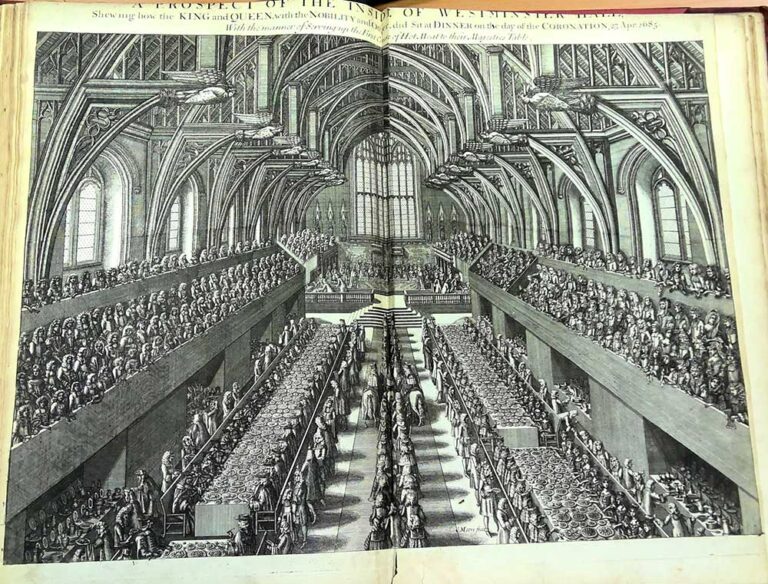

After the investiture and crowning, everyone proceeded from Westminster Abbey to Westminster Hall for the royal feast. Again, Sandford provides us with a lot of detail. As well as describing who was seated where, he lists the 144 dishes served as the first course to their majesties, and the dishes placed at the upper end of the first tables on the West and East side of Westminster Hall. There is a diagram showing how the tables were positioned in the hall, and which plate of food was placed where upon the tables as well as engravings of the interior of the hall.

Samuel Moore, a draftsman at the Customs House in London as well as an engraver, provided a fine illustration of the interior of Westminster Hall, with everyone seated at the coronation feast.

Sandford concludes his description of the coronation day by saying that the fireworks display upon the river Thames was held the following evening ‘by reason of the great fatigue of the day.’

Unfortunately for Sandford, by the time his book was printed in 1687 the mood of the country was turning against James II and sales of the book barely covered the cost of production. He was blighted by financial difficulties throughout his career and died in 1694 in a debtor’s prison.

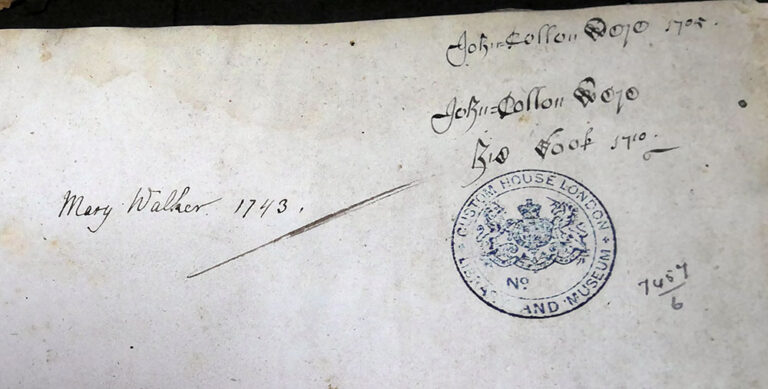

Information about the former owners and bindings of our early printed books is gradually being added to the catalogue records by the library team and volunteers.

While the binding of our copy of this book is uninteresting, there are inscriptions of two 18th-century owners as well as the stamp of the Custom House Library and Museum on the flyleaf. There is also a manuscript note on one of the front endpapers which reads ‘Presented to the Customs Museum by William Gronow, Clerk at Swansea, 7 July 1858.’ This is undoubtedly the same William Gronow who appears in the 1861 census as a Clerk in Her Majesty’s Customs and living in Swansea with Elizabeth, his widowed mother, a sister and two brothers.

We don’t know when the book was transferred to the then Public Record Office, but it was prior to 1902 because it is listed in that year’s edition of the Catalogue of the Library in the Public Record Office.

You can consult this and other items from our rare books collection in the Invigilation Room at The National Archives if you have a reader’s ticket. Along with the main library collection, this book can be found on the library catalogue, which is separate from Discovery, The National Archives’ catalogue.

Bibliography

- Sandford, Francis, The history of the coronation of the most high, most mighty and most excellent monarch, James II … and of his royal consort Queen Mary : solemnized in the Collegiate church of St. Peter in the city of Westminster, on Thursday the 23 of April … 1685. With an exact account of the several preparations in order thereunto … By his Majesties especial command. (1687)

- Sherlock, Peter. “Sandford, Francis (1630–1694), herald and genealogist.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 23 Sep. 2004;. (Subscription required. Accessed 19 April 2023)

- Griffiths, Antony. “Sherwin, William (b. c. 1645, d. in or after 1709), engraver and inventor of a method of mezzotinting.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 23 Sep. 2004;. (Subscription required. 19 April 2023)

- Clayton, Muriel, and Alma Oakes. “Early Calico Printers around London.” In The Burlington Magazine, Vol.96, No.614, 1954, pp. 135–39. JSTOR;. (Academic subscription required. Accessed 19 April 2023)

- Cust, L. H., and Timothy Clayton. “Moore, Samuel (fl. 1680–1720), draughtsman and engraver.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 23 Sep. 2004;. (Subscription required. Accessed 19 April 2023)

- Wagner, Sir Anthony Richard, Heralds of England: a history of the Office and College of Arms (1967)

- RG 9/4102 folio 49, page 46; Findmypast.co.uk (Subscription required. Accessed 19 April 2023)

- Abbott, Sarah. “The National Archives’ library in focus” In Magna: the magazine of the Friends of The National Archives, Vol. 33, No. 2 November 2022, pp. 32-35

A fascinating record