The 1918 General Election saw 17 women across the political spectrum stand for Parliament for the first time, 15 of whom had backgrounds in the women’s suffrage movement. Taking place on 14 December 1918, the election was just three weeks after the passing of Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act on 21 November. This act enabled women over the age of 21 to stand in parliamentary elections.

This blog focuses on Constance Markievicz, who was selected as a Sinn Féin candidate for Dublin St Patrick’s. She stood against the Irish Parliamentary Party candidate, William Field. Markievicz was in Holloway prison during the election for her involvement in anti-conscription activities during the First World War, and she had previously been imprisoned for her involvement in the Easter Rising in 1916. Indeed, the only reason she was not executed for treason was because she was a woman (see footnote 1).

Women candidates experienced numerous challenges in the 1918 General Election, such as difficulties in getting selected, lack of funds, and limited time to establish themselves in the constituency (see footnote 2). Markievicz was the only woman to win her election contest in 1918, but along with 72 other Sinn Féin MPs, she was not prepared to take the oath of allegiance to the British crown and, refused to take her seat in the House of Commons.

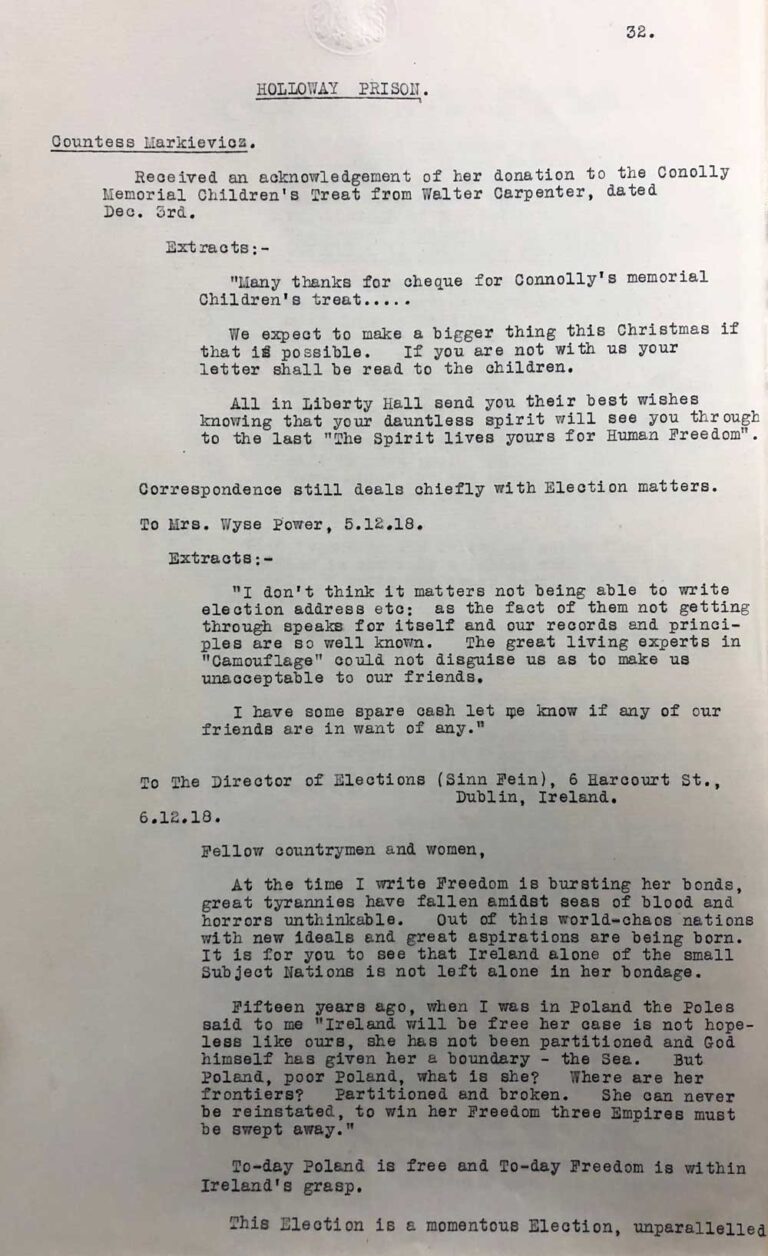

The National Archives holds a large amount of material on Markievicz and her election campaign in the Home Office and Colonial Office records. However, it is important to acknowledge that the only reason The National Archives has this material is because the government was monitoring her correspondence in prison, as it was for all Irish republican prisoners, and was also censoring material. Nonetheless, these records provide a unique insight into Markievicz’s election campaign, both in terms of the logistics of how it was run and the causes that she championed.

The 1918 General Election was significant in many ways. Not only was it the first election in which women could stand, it was also the first time that women over 30 who met a property qualification could vote, as well as all men over 21, following the passing of the 1918 Representation of the People Act. Interestingly, the press labelled 1918 as the ‘women’s election’. The election took place in the aftermath of the First World War, and the Conservatives and Lloyd George Liberals fought the election under the Coalition banner.

During the election campaign, Markievicz wrote to her sister, Eva Gore-Booth, ‘I was actually allowed a big bit of paper to write an Election Address on! I wrote one in such a hurry that it’s probably not sense!’ (See footnote 3.) The election address was a leaflet posted to each household in the constituency and was the main way in which a candidate could set out their cause to voters (see footnote 4). As a result, it is notable that Markievicz was able to write an election address in prison.

Markievicz began her election address by declaring:

‘At the time I write Freedom is bursting her bonds, great tyrannies have fallen amidst seas of blood and horrors unthinkable. Out of this world-chaos nations with new ideals and great aspirations are being born. It is for you to see that Ireland alone of the small Subject Nations is not left alone in her bondage.’

Constance Markievicz’s 1918 election address, 6 December 1918, CO 904/164, The National Archives

She subsequently went on to call for ‘Complete and unlimited self-determination for Ireland’, emphasising that Markievicz’s main cause was independence and freedom for Ireland (see footnote 6). The end of her election address read ‘I also address our women, armed with their new weapon – The Vote – I know they will use it well’ (see footnote 7). Throughout the interwar period, women candidates often addressed the female electorate, and Markievicz’s use of the terms ‘armed’ and ‘weapon’ are particularly noteworthy.

As Markievicz was unable to undertake campaigning activities herself, such as speaking at election meetings and canvassing, her election campaign was run largely by female republicans and women suffrage activists (see footnote 7). Those campaigning on her behalf sent her updates, although few of these survive in The National Archive’s records. This may suggest that not all of these letters got through to Markievicz. Nonetheless, the correspondence in the collection is helpful in understanding how Markievicz’s election campaign was progressing.

C.F. Stafford wrote to Markievicz ‘I would have written sooner but every second is now taken up at Election work, and we often don’t get our tea until 11 p.m.…We are getting on splendidly in all the Wards.’ (See footnote 8.) Moreover, Markievicz wrote to Hanna Sheehy Skeffington, a suffragette and Irish nationalist, ‘Many thanks for your card received some days ago. I have received so few letters since the Election Campaign began that I begin to think the Censor is holding them up. I don’t even know if my election address was let pass.’ (See footnote 9.) Although we know that Markievicz’s election address was let through, this shows that she was initially unsure of how her campaign was going.

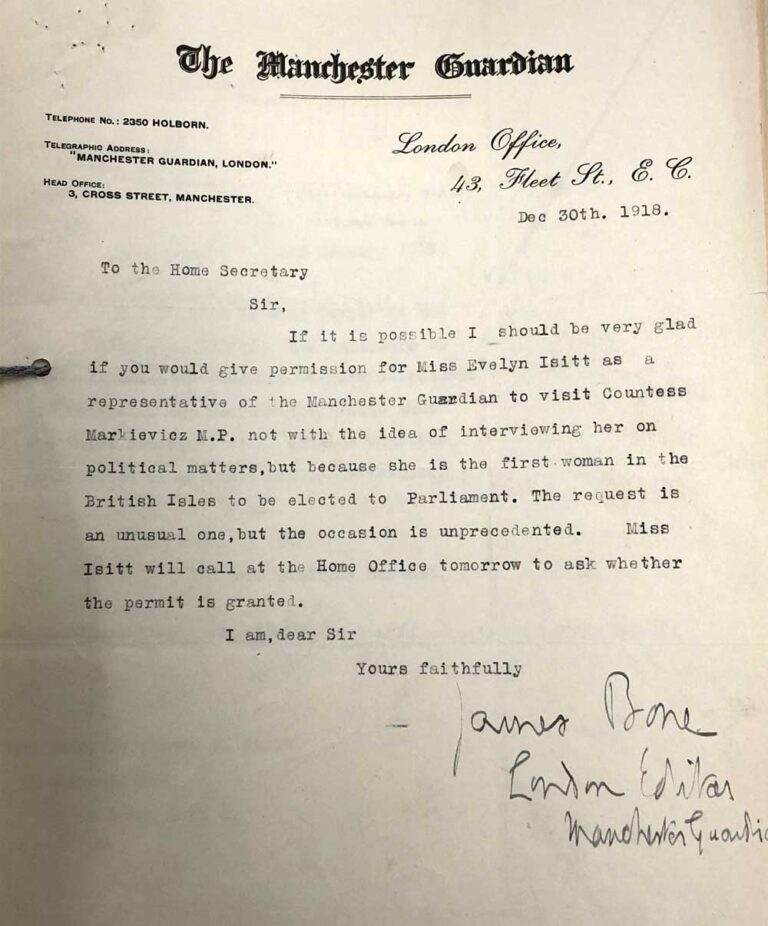

Curiosity surrounded Markievicz’s success as the only woman elected in the 1918 General Election. The London editor of the Manchester Guardian, James Bone, wrote to the Home Secretary, George Cave, after the election, and asked if Miss Evelyn Isitt, a representative of the newspaper, could visit Markievicz in prison. The letter stated that it was ‘not with the idea of interviewing her on political matters, but because she is the first woman in the British Isles to be elected to Parliament. The request is an unusual one, but the occasion is unprecedented.’ (See footnote 10.) Although the request was declined, this shows the interest that surrounded the first woman MP and her circumstances at the time. Furthermore, this letter emphasises the historical significance of Markievicz’s election to Parliament.

Although Markievicz did not take her seat in 1918, her election success proved that a woman could win a parliamentary election. The National Archives records provide an interesting insight into Markievicz’s election contest at a time when she was unable to physically campaign herself. Markievicz was subsequently elected the First Dáil (Irish Revolutionary Parliament) in 1919 and also served as Minister of Labour, becoming the first Irish female cabinet minister.

Footnotes

- Schedule for Constance Markievicz’s offence in the Easter Rising, HO 144/1580/316818, The National Archives.

- For more information on women candidates and the 1918 General Election, see Lisa Berry-Waite, ‘The ‘Woman’s Point of View’: Women Parliamentary Candidates, 1918-1919’, in David Thackeray and Richard Toye, eds, Electoral Pledges in Britain since 1918: The Politics of Promises (Cham, 2020), pp. 47-69.

- Letter from Constance Markievicz to Eva Gore-Booth, 12 December 1918, cited in Constance Markievicz, Prison Letters of Countess Markievicz (London, 1987), pp. 197-8.

- David Thackeray and Richard Toye, ‘An Age of Promises: British Election Manifestos and Addresses 1900-97’, Twentieth Century British History, 31 (2020), pp. 1-26, p. 6.

- Constance Markievicz’s 1918 election address, 6 December 1918, CO 904/164, The National Archives.

- Constance Markievicz’s 1918 election address, 6 December 1918, CO 904/164, The National Archives.

- Senia Pašeta, Irish Nationalist Women, 1900-1918 (Cambridge, 2013), p. 262.

- Letter from C.F. Stafford to Constance Markievicz, 11 December 1918, CO 904/164, The National Archives.

- Letter from Constance Markievicz to Sheehy Skeffington, 18 December 1918, CO 904/164, The National Archives.

- Letter from James Bone to the Home Secretary, George Cave, 30 December 1918, HO 144/1580/316818, The National Archives.

British gals could, at age 21, be candidates to the British House of Commons but … to vote these same women had to be 30 years old 👀.

Very British indeed …

very interesting.

Who was Count Markievicz and how did the young Constance Gore-Booth come to meet and marry him?

I found this topic interesting and thought provoking. This is a recent event in UK history and yet not taught in schools to my knowledge. My belief is young people should be taught political history, the good and bad. Encourage young people to think about how these events effect today’s UK. What do they see as major changes happening now and how they personally effect the country moving forward. See a future that requires their involvement to make positive strides forward for al people in the UK.

The willingness of Labor to step down during this election permitted Sinn Fein candidates a clearer field to success

The Liberals promised women the vote as a reward for having backed up the home front during the 1st world war instead of pursuing women’s sufferage. This promise may have seemed fair and just but it still held women back. Only landed women over the age of 30 could vote although women over 21 were supposedly allowed to stand for parliament. The truth is the government could not let all women vote because then women would be running the UK. The carnage that was the 1st war followed by Spanish Flu, left men by far the minority sex in the UK.

All women weren’t allowed to vote till 1928 when the male adult population had somewhat recovered.