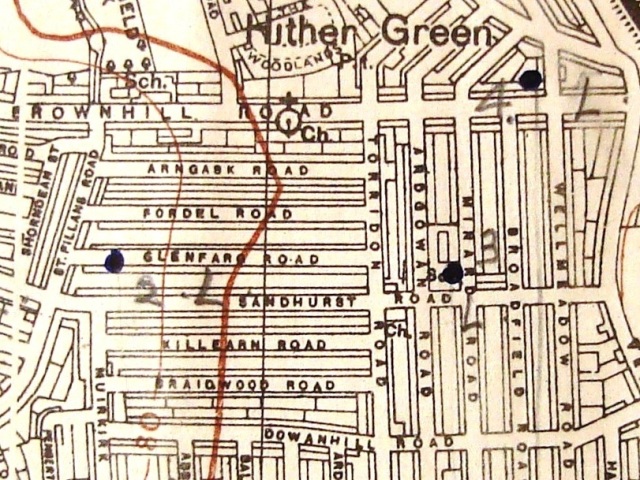

Kew and environs, as seen on BombSight.org

The title of today’s blog post comes from the first stanza of the poem Slough, by John Betjeman.

Come, friendly bombs, and fall on Slough!

It isn’t fit for humans now,

There isn’t grass to graze a cow.

Swarm over, Death!

In reality, of course, air raids during the Second World War would have seemed anything but friendly to those on the receiving end. [ref] 1. Betjeman’s poem was published in 1937, two years before the beginning of the Second World War. During the war, it must have seemed in extremely bad taste. [/ref]

Many of you will already have heard about the new Bomb Sight website, developed by the University of Portsmouth, with funding from JISC. Bomb Sight is based partly on selected Bomb Census maps held here at The National Archives and allows users to identify where bombs fell during the London Blitz, between 7 October 1940 and 6 June 1941. We are delighted that interest in the website, both from the media and the public at large, has been much greater than the project team had anticipated.

Second World War bombing is not an easy or straightforward topic to research. Finding out as much as you possibly can about a single bombing incident often involves looking at many different sources. Here is an outline of some of the most useful ones.

Online sources

Although detailed information about specific bombs is not often available online, there are many different websites that include relevant material. These are some of my favourites:

- West End at War, developed by Westminster City Archives

- Bath Blitz Memorial Project, about the devastating raids on Bath in April 1942

- North-East Diary, 1939-1945, about the wartime experience of north-eastern England

West Yorkshire Archive Service has plotted some bombing locations in the West Riding of Yorkshire onto Google Maps. Twitter users can also follow the West Riding’s wartime ARP [ref] 3. ARP stands for Air Raid Precautions, but the abbreviated form is probably more familiar than the full form. [/ref] service, tweeting as @WR_ARP.

As well as commemorating those who died on active service, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission has recorded the names of civilians who were killed during bombing raids.

Published books

Many books have been written about air raids and other aspects of life on the home front during the Second World War. David Blomfield and Christopher May’s Kew at War and Peter Doyle’s The Blitz are just two examples.

A facsimile edition of the London County Council bomb damage maps [ref] 4. The original maps are held at London Metropolitan Archives. [/ref], edited by Ann Saunders, was published in 2005. Although this is now out of print, copies are available in many libraries, including our own reference library.

Old newspapers

Newspaper reports at the time often mentioned specific raids or individual bombs and their effects, although details can be rather vague. In particular, newspapers tended not to mention the names and precise locations of buildings that were destroyed or severely damaged. This was to prevent the enemy from finding out too much about the impact of the bombing.

The largest collection of British newspapers is held at the British Library’s newspaper library. Many local archives and local studies libraries have excellent collections of local newspapers from the Second World War period.

Original records

Some Ministry of Home Security files include photographs, like this one of bomb damage to houses in Kew in 1944. (Document reference: HO 192/862)

The National Archives holds bombing records created during the war by the Ministry of Home Security. As well as the Bomb Census maps (in record series HO 193), these include forms listing individual bombs (in HO 198) and files about selected incidents (in HO 192). Other relevant records include the reports on ‘key points’ such as utilities and some factories (in HO 201) and high-level reports (in HO 202 and HO 203).

For more information, take a look at our research guide about the Bomb Census. [ref] 5. We plan to update this guide soon. [/ref] Many of these records are fragile, so if you visit us to look at any of them, please handle them very carefully.

Sometimes, you can also find information relevant to bombing incidents in records of other government departments. Examples include:

- CO 981/15 – A Colonial Office file including information about the death of Kenrick Johnson in an air raid on 8 March 1941.

- OS 1/196 – An Ordnance Survey file about bomb damage to its Southampton building.

- WORK 14/1392 – A Ministry of Works file recording bomb damage to historic buildings in Bath.

Many other archives also hold relevant records. These vary quite a lot: in some cases, they can be more detailed than those held here at The National Archives but in other cases they are less informative. They may include ARP wardens’ logs or incident registers, as well as maps and photographs. Seemingly dry records such as local council minutes can be surprisingly informative, if you have the time to read through them.

Finally, some archives even hold more personal records, such as diaries of individuals who lived through air raids. These can offer a different, more intimate, perspective on events from the ‘official’ records of government departments and other organisations.

Part of a Bomb Census map (sheet number 56/18 NE) showing South London in January 1943. (Document reference HO 193/31)

I would add two other files at TNA which might be useful T 164/194/15

“Hewelcke, T, killed by bomb whilst on Home Guard duty outside office” (this file is held at the ‘Salt Mines’ in Salford and needs 3 working days notice to see) and

AIR 8/356 “Bomb dropped on Slough on night of 13th July 1940: investigation”

(there is also a Cabinet file on this event). Buckinghamshire County Council do have some specific pieces of information online for the county.

Thank you, David. It can be surprising how much detailed information about some bombing incidents exists – sometimes in quite unexpected places.

Another local resource like West Yorkshire’s is London Borough of Sutton’s Google Bomb Map for Sutton & Cheam http://bit.ly/T8qyMI – it covers the whole war and because it’s based on local contemporary records is detailed down to address, date and time. So as Andrew does I urge researchers to go local as well and I would also repeat Andrew’s comments about the CWGC website including civilians – not everyone realises that.

Kath Shawcross, LB Sutton Archives

Thank you, Kath. That’s a really useful resource.

It’s very gratifying to see that the media interest in Bomb Sight has helped to raise awareness of other relevant online sources too.

Talking of other relevant online sources, by a happy coincidence, the bomb damage maps from Manchester Archives and Local Studies have just been made available on the University of Manchester’s website: http://www.manchester.ac.uk/aboutus/news/display/?id=9245