Why recruit the Chinese Labour Corps?

As the First World War progressed, the need for more manpower became acutely problematic. The increased use of ammunition and supplies necessitated by trench warfare led to increased imports, which in turn put enormous strain on the transportation services. Depots, workshops, factories and ports were all desperate for manpower. At the start of the war in August 1914, there was no body of men trained or designated for these tasks. The British War Office had to put forward its troops for manual work near the front lines in the form of Pioneer Battalions, which were added to each Division.

It was the realisation of this huge task that would be necessary to prepare for the great offensive of 1917 that first persuaded the British Authorities to consider the importation of Chinese labourers to France and Belgium. The tremendous losses seen during the series of British offensives of 1915 meant that labourers who previously worked behind the front line were now required to go to the front.

By August 1916 the War Office had made an enquiry to Sir John Jordan, British Minister in Peking, for his view regarding the prospect of employing Chinese labour. The scheme was given the go-ahead and by 3 September 1916, the War Office had appointed Mr T. J. Bourne – Engineering Chief of the Pukow- Hsinyangchou Railway – as a representative and recruiter. At first, the scheme was to recruit labourers from British Territory in Hong Kong to avoid difficulties regarding China’s neutrality. However, it became clear that labourers from Hong Kong were not suited to the cold climate, as stated by Military Attaché’ Robertson:

‘…the men would be Cantonese and Cantonese are not accustomed to a cold climate. This might be sufficient to prevent the scheme being carried out.’

As the recruitment in Hong Kong was not recommended, the Military Attaché presented two alternatives. The first was to enlist Chinese labourers under private contractors as the French did. Once recruited, the labourers would be shipped from the treaty ports (i.e. ports that were open to foreign trade and residence). This method would be carried out under Liang Shih Yi, Director-General of the Customs Administration. The second option was the enrolment by the British Government of Chinese labourers in Wei-Hai-Wei, a British-leased territory. The War Office – after consultation with Sir John Jordan and the Foreign Office – approved the latter method and by the beginning of October 1916 recruiting agent Forbes and Co., who ran the scheme that recruited Chinese labourers to South African gold mines in 1904, was appointed.

The recruitment

The French pioneered the scheme to recruit labourers to serve as non-military personnel, with negotiations being conducted by government officers posing as civilians to protect the Chinese Government and its neutrality. The contract to supply 50,000 labourers was agreed upon on 14 May 1916 and their first shipment left Tianjin for Marseilles in July 1916.

With regard to British plans following the negotiations with Beijing, the Government and the War Office made the initial decision to use Wei-Hai-Wei as a recruiting depot. This was a result of a compromise between the urgent need for the manpower and a strict legality regarding the politics and diplomacy of China. On arrival at the Labour Depot at Wei-Hai-Wei, the prospective recruits were given accommodation and food by Forbes and Co..

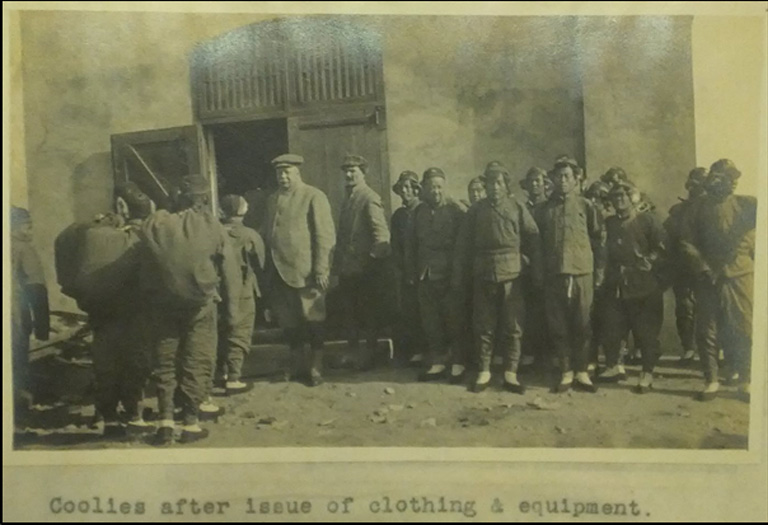

Each recruit was allotted a number and given a brass disc for identity. In order to become a member of the CLC, the recruit needed to pass medical inspection. They then received a uniform and equipment. The Wei-Hai-Wei depot allowed the British to recruit without restriction and by January 1917 the first Battalion of the CLC was ready to sail. At the same time, the War Office appointed Lt. Col. Bryan Charles Fairfax and Major Richard Ireland Purdon to organise the headquarters of the CLC and the Chinese Depot, as well as the Native Hospital at Noyelles sur Mer near Abbeville.

Chinese labour recruits after issue of clothing and equipment (catalogue reference: FO 371/2905/397)

Transportation of Chinese Labour Corps

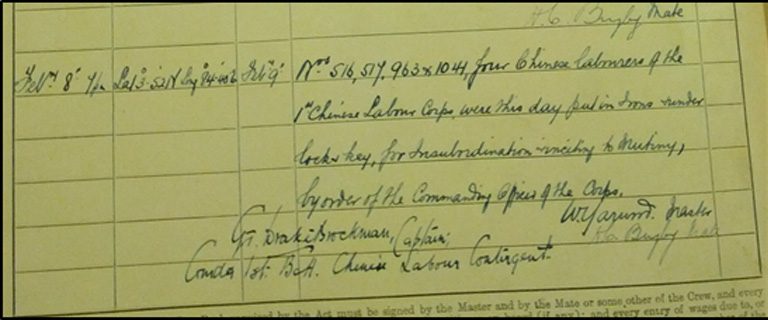

The first contingent of Chinese labourers (1086 under six British officers and one Medical Officer) left Wei-Hai-Wei on 18 January 1917, on the Teucer. The route took them via Yokohama, Singapore, Durban and Cape Town, arriving at Havre on 19 April 1917. However, during transportation there was evidence of defiance of authority from some, as show in the ships’ official logs; four of the Chinese labourers were detained for subordination and inciting a mutiny.

Ships’ official logs ‘Teucer’ (catalogue reference: BT 165/1663)

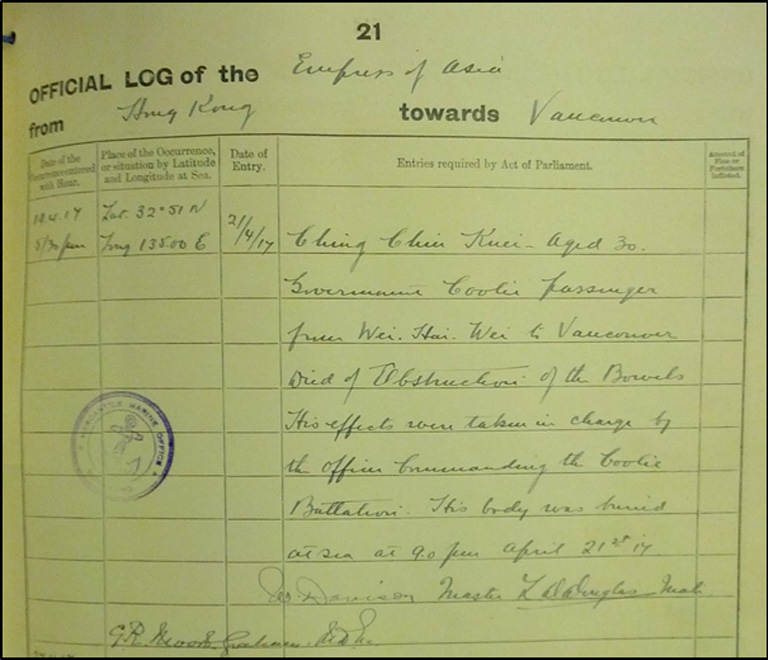

After Germany’s resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare on 1 February 1917 – followed shortly after by the sinking of the Athos, causing the loss of over 500 of the French-recruited Chinese labourers – the British sought to minimise the risk by reducing the time their own recruits would spend at sea. In March 1917, the Colonial Office approached the Canadian authorities for assistance. The plan was to transport the labourers from Wei-Hai-Wei to Canada and land at William Head in Vancouver Island, where they would be held at the old quarantine station. The voyagers’ conditions were varied – some crossings could be extremely rough and many of the labourers were not used to travelling on water – the official log of the Empress of Asia records deaths during the transit, including that of Ching Chin Kuei, who died from an obstruction of the bowel and was buried at sea.

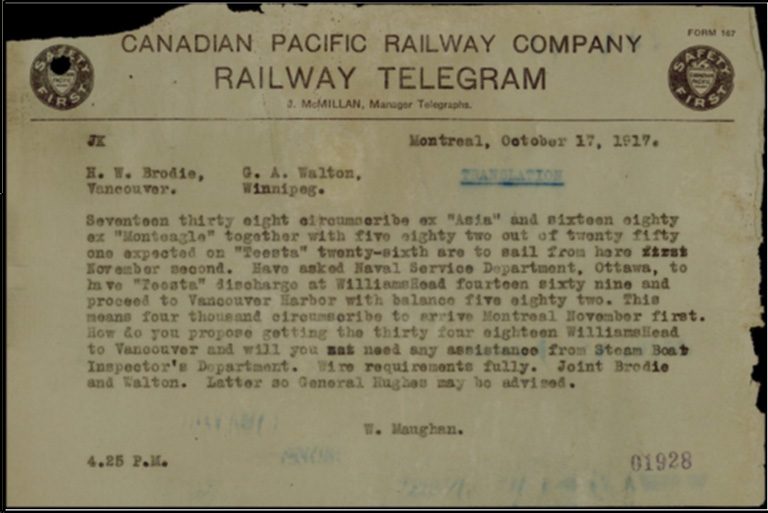

Following authorisation from the quarantine station, the labourers boarded the train provided by Canadian Pacific Railway Company to Halifax, Nova Scotia. During this land journey, the Canadian government banned all news outlets from reporting on the train convoys that crossed the country on their way to France. Once at Halifax, the Chinese labourers would be shipped to Liverpool or Plymouth in the UK, then from Folkestone on to Noyellessur-Mer in France.

Ships’ Official Logs ‘Empress of Asia’ (catalogue reference: BT 165/1725)

Chinese labourers, Overseas (Library and Archives Canada, accession number 1048-45-2 Vol 5)

‘A’ Company, 1st Battalion, Chinese Labour Corps (catalogue reference: FO 371/2905/396)

Working in France

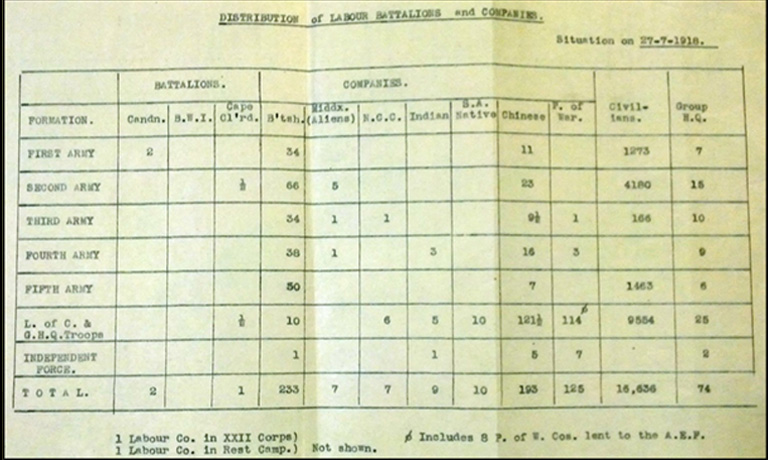

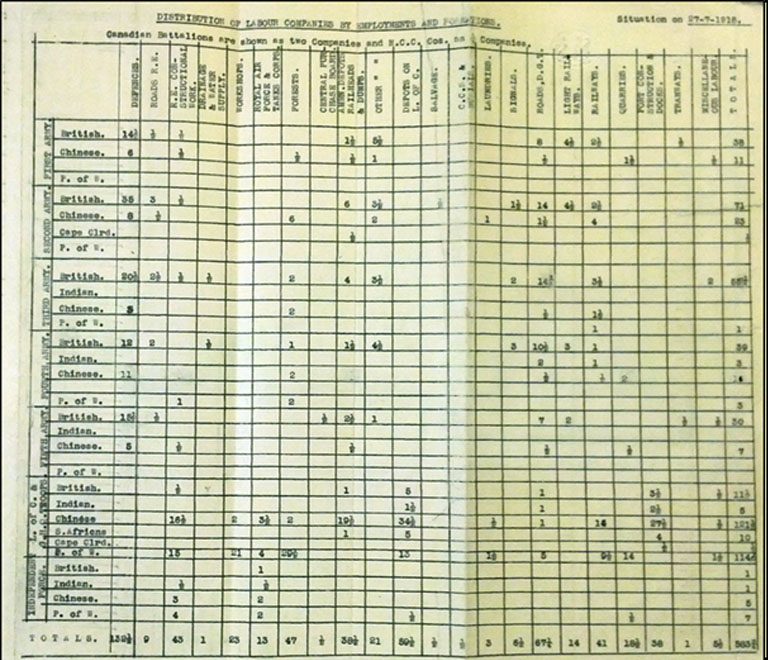

The plan to raise Chinese labour units was initially proposed by the War Office for a target of ten thousand labourers, or about 20 companies, which was set out by the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Andrew Bonar Law. The distribution of these Chinese labour companies was first done by DGMR (Director-General Movements and Railways), under the DGT (Director-General of Transportations) Sir Eric Geddes. But the QMG (Quartermaster General) decided that it was impracticable to hand these Chinese over for administration as well as all work under DGT. Therefore 14 of these first 20 CLCs were to work under DGT. Of these, the 1st , 4th and 6th companies were to work under CEPC (Chief Engineer Port Construction) for Port construction, consisting of men of suitable trades or easy to train for this sort of work. The 2nd, 3rd, 5th and 7th companies worked under CSKP on Transportation and Stores. Then seven CLC companies were employed in the Labour Pool at the Northern ports for work under the Department of Docks. The remaining six companies were distributed to Armies and Line of Communication. A typical CLC consisted of a headquarters and four platoons each under a subaltern. Each platoon consisted of two sections, each under a sergeant. Each section consisted of two subsections, each under a corporal. There were between 470 and 490 Chinese, which included 32 gangers of classes 1, 2 and 3 in each company. By the end of the hostility in 1918, there were about 195 Chinese Labour companies in all (approximately 95,500 Chinese labourers). The tables below represent a common distribution of labour battalions and companies (Table 1) and distribution by employments and formations (Table 2) for the situation on 27 July 1918.

Table 1: Distribution of Labour Battalions and Companies (catalogue reference: WO 107/37)

Table 2: Distribution of Labour Companies by Employments and Formations (catalogue reference: WO 107/37)

As Chinese labourers started to arrive at the Western Front, there were no special arrangements in regard to “skilled” companies. However, a census was made of the trades of everyone passing through the depot, based on an oral examination. There was no regulation with regard to the tradesmen, and no special demands for skilled labour had been received. Around May 1917, the decision to regularise the position of Chinese skilled labourers and tradesmen was taken at Conference at HQ CLC at Noyelles. Special rates of pay were proposed for these skilled labourers and agreed by the War Office by the end of August 1917.

Branches and Services. Labour Commandant (catalogue reference: WO 95/83/2)

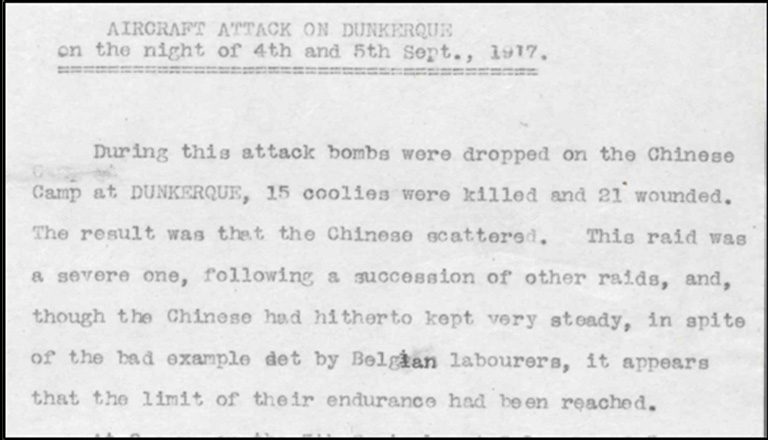

During the Flanders Offensive in 1917, many Chinese labour companies replaced the British labour companies, who were sent from the Line of Communication from the Southern to the Northern Armies area (which at this time were occupied by the Second and the Fifth Armies). Between 4 and 5 August 1917, Dunkirk suffered enemy air raids which resulted in 12 Chinese labourers being killed and 32 wounded. These air raids caused panic and led to the dislocation of Chinese labour corps, as shown in the Labour Commandant’s war diary.

With the United States’ entry into the war in April 1917, Britain and France needed to transport American troops, not Chinese labourers. China abandoned its neutrality and declared war on Germany and Austria-Hungary in August, eager to have a seat in post-war negotiations. Russia quit the war as the Tsarist empire crumbled in the world’s first Communist revolution in October 1917, stranding hundreds of thousands of Chinese workers in the former empire. Ten days before Germany’s surrender on November 11, 1918, Britain sent back the first batch of 365 Chinese workers, beginning repatriations that ended in September 1920. By the end of the war, the Chinese had already begun to form an established community in France. The republic had workers stay to help rebuild after the fighting. About 3,000 Chinese labourers remained in France and settled down, forming Chinatowns.

[…] techadmin on January 18, 2017 Chinese Labour Corps on the Western Front2017-01-18T18:20:32+00:00 – Journals & Publications – No […]

I found this article on Chinese Labour corps was really informative especially with the pictures which accompanied the article, seeing the type written records, the receipts and the photos made what had happened to the Chinese labour corps palpable and real.

These men left behind very few records and so well done for helping to piece together what is a largely forgotten history- thank you!

Hi Sulin,

Thank you very much, it is a history that need to be told.

Pad

This is a very comprehensive article about the recruitment of Chinese laborers by the British Government. One question to the author by someone who is investigating the sites where these laborers were stationed . Where should I write to obtain information regarding the extent of the camps, in particular those near the harbours of Dunkerque, Dieppe, Saint Valery sur Somme ? . There is little left about these camps on the french side, but great curiosity about what these facilities consisted of. In one instance I read about the establishment of a 1,500 bed hospital for the Chinese laborers. I’d appreciate feedback and advice from the author of the article of whom or which agency to trace the information of available mass plans .

Hi Edouard,

It is very difficult to trace the sites where these labourers were stationed. Once they were shipped to France the Chinese labourers were allocated to various Army units. I think the best place to start is to consult ‘The Chinese Labour Corps 1916-1920’ by Gregory James, which give an account of the CLC service in Europe. For primary sources at TNA we have history of the Chinese Labour Corps in WO 106/33, which provide you with detail of the recruitment and organization of the Corps. We also have unit war diary in record series WO 95 as well as selection of several types of medical records from various theatres of war in MH 106, but as the Chinese labour companies were scattered throughout, to find the relevance one is a time consuming as you will need to know which Army area they were attached to.

I hope this answer your question

Pad

Could the National Archives publish the evidence for the CLC crossing from Folkestone? While there was a CLC camp at Folkestone the men from this camp crossed to France from Southampton.

Hi Peter,

According to the diary of voyage the HMT Ulua (FO 228/2893), this was one of the CLC transporters from Canada to England. After the ship reached Liverpool at 4 AM on 24 January 1918, and until 27 January the CLC were taken off the boat by tender and entrained at Liverpool by 4 PM. By 1 AM of 28 January CLC reached Shorncliffe and by 7.30 AM embarked for France and reached Boulogne at 11.30 AM.

As you can see from the circumstantial evidence, which point to the fact that at least CLC from this ship were indeed crossing from Folkestone. I think it was to spend as little time as possible in the English Channel !!!

I hope this answer your question

Pad

I want to have informations about the companies of CLC who were à Audruicq (railways, amunitions), Ruminghem (hospital ), Zenegham (great camp for railways, amunitions) from april 1917 to 1919. particularly for Ruminghem where a chinese cimetary for 75 persons is situed ,

one part is die at St Pol Sur Mer (not far from Dunkerque), the other part is die in the area of Zenegham or Audruicq. photographies of the camps will be very interesting, I have IWM (Q7459) and (8207-38)

.

Thank you for your answer.

Hi Francine,

We can’t help with research requests through the blog, but please go to the ‘contact us’ page on our website: https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact-us/

You’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts by phone, email or live chat.

Best regards,

Liz.

Hi Francine Thorel,

Found this link, hope helps.

https://www.cwgc.org/find-a-cemetery/cemetery/68503/RUMINGHEM%20CHINESE%20CEMETERY

Ashley

Above the paragraph of the last picture, the last sentence: Special rates of pay were proposed for these skilled labourers and agreed by the War Office by the end of August 2017.

was it supposed to be 1917 ??

Hi Ashley,

Thanks for spotting the typo! I’ve fixed it.

Best regards,

Liz.

Hi Pad.

I was re-reading your reply to me regarding the CLC crossing from Folkestone to Boulogne.

Arriving at Shorncliffe at 1 am and embarking for Boulogne at 7:30 arriving at Boulogne at 11:30 am. 4 hours on a boat across this point of the channel in daylight is a very long time. 2-3 times longer than it normally took.

It would be interesting to see that page in the Ulia diary/log.

Peter

To the site keeper, I wrpte a coment last march 2017 and only see it TODAY . What’s the use of giving my email account if you do not inform people that a few daysor several months hereafter one does get an answer! The methods of communication are not that great . Please discuss with your management how you can improve the process. Possibly communicate with me directly since I give you my email address

Also my last comment was made on March 8 . Pad’s reply was given June 28 i.e. over three months afterward. I suspect PAD was not communicated the message for a significant amount of time . My comment is somewhat repetitive to the one I just posted above!

I see dome replies to good questions , and would like to seek s areply about the camp of Noyelles or Nolette which according to recent publications tend to say most CLC were transiting through it .

before being affected to field installations . Noyelles/ Nolette had a hospital facility built for 1,500 chinese people (yes that many!) as per visitors testified in early 1917. Three questions please : 1. was the facility actually used for CLCs ? 2. Is there anywhere a camp map of the facilities In France people say the whole camp was around 42 hectares ( 600mx 700m) ? 3. How was this used space used , as I don’t think it had any assembly or repair facilities?

If I am barking at the wrong tree for these questions of great interest to me , can you direct me to the right people within N.A> Please recall phone calls are expensive when you are a non- U K resident and that email addresses are better proxies for contacts and exchanges.

Yours Truly –in hope of a reply within a few weeks–

Dear Edouard,

Thank you for your comment.

I’m sorry there was a delay between you posting your original comment and receiving a reply. I’m afraid we can’t guarantee a full response to research requests submitted through the blog.

The best way to contact our records experts is to go to our ‘contact us’ page at http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ – this shows you how to get in touch via email, live chat or phone call.

Best regards,

Liz.

Hi All;

For those of you who are really serious about this subject matter;

here are a few pointers….

CHINA

On The Western Front.

Britain’s Chinese Work Force in the First World War.

Auth: Michael Summerskill

Pub: 1982. By: Page Bros. (Norwich) Ltd.

Even this is essentially a synopsis…

Oddly enough; available in Paperback Only…

——————————–

[content edited]

by Lt. Daryl Klein

ISBN: 9781286059371

——————————-

And of course the one by Gregory James Published by: Bayview Educational: 2013.

But; that is practically generic now!

There are a few more; but that would be telling!

(*Clue they are all Private Publications, and the originals are all in Private Collector’s hands!*)

———————————

If u r really super-lazy; then watch the up coming film by:

‘Tricks On The Dead’ : The story of the Chinese Labour Corps in WWI.

Dist: Rare Earth Media Group. Out: Sept. 2017.

————————-

Enough said:

From:

A Serious scholar on the Topic!

[…] a Royal Navy Stoker who had died serving on HMS Cressy, and for Liu Hsi Ju, a member of the Chinese Labour Corp, who was one of thousands of Chinese to die in British […]

Hi All;

Changing tack a little here; are there any serious scholars here who are interested in the

World War Two theatre….

I am quite keen on Joseph Warren Stilwell; myself…He was a Four Star General you know!

US Army obviously…

P.S.

Oh; the book by Klein was called;

“With the Ch__ks!”

Oddly enough; the actual content was quite sympathetic to the Chinese indenture…

Despite the title. Just goes to show; u can’t judge a book by it’s title…or cover…

Manchester Museum has a Chinese honorific umbrella presented to the collection by a Lieutenant Thomas Walsh who served as an Officer with the 119th Company Chinese Labour Corps in France in September 1917. We are aware of other gifts of honorific umbrellas when a respected officer received a promotion. We intend to show the umbrella in a new China Gallery opening in 2021. We would be interested to learn of any photographs of 119th Company that we could reproduce in the displays.

Thanks,

Bryan Sitch

Deputy Head of Collections

does anyone know of a 2nd Lieutentant named Frederick Butler Madden who served with the Chinese Labour Corp.( discharge date August 1922 number 7/20904)

I

Hi Irene,

Thanks for your comment.

We can’t answer research requests on the blog, but if you go to our ‘contact us’ page at http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts by email, live chat or phone.

Best of luck with your research.

Kind regards,

Liz.

[…] https://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/chinese-labour-corps-western-front-2/ […]

[…] https://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/chinese-labour-corps-western-front-2/ […]

Bonjour,

Who can help me to find documents abot Mr. Liu Sssi or Liu Ssu, chinse laborer n°130745, dead on 7th April 1919 and buried at Les Rues des Vignes, near Cambrai in the north of FRance). Thank you

Dear Mr Gabet,

Thanks for your comment.

We can’t answer research requests on the blog, but if you go to our ‘contact us’ page at http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts by email or live chat.

Kind regards,

Liz.

I’m very interesting with your article.

Hi All at the Archives;

Full marks to: (GABET) as to another lesser known burial site of our C.L.C. brethren in Northern France.

Now here is the best I can do with only a quarter of the map that was published by:-

Michael Brynar Summerskill way back in 1982.

————————–

In Belgium.

Ostend. /Furnes. /Proven /Poperinghe /Dozinghem /Ypres /Lijssenthoek /Menin

————————–

In N.E. France

Dunkirk /Eringhem /Caestre /Hazebrouck /Tourcoing /St Andre /Lille /Ascq. /Bourbourg /Audruicq

/Ruminghem /Moulle /St.-Omer /Caestre /Hazebrouck /Pont-de-Briques /Audruicq /Ruminghem

/Tourehem /Moulle /Arques /Calais /Bleriot-Plage /Pont-de-Briques /Longuenesse /Seninghem

/Wimereux /Terlincthum /Boulogne /Hardelot-Plage /Dannes-Camiers /Etaples /Berguette /Lapugnuy

/Bethune /Houdain /Huby-St-Leu /Hesdin /St. Pol-Sur-Ternoise /Duisans /Arras /Ayette /Pommereuil

/Doullens /Noyelles-sur-Mer /Abbeville /Flixecourt /Amiens /Tincourt /Nesle /Ham /Abancourt

/Le Havre /Rouen /Dieppe and ******************* Finally; Paris.

One Should also note that over the years the well-known story of The Monocled Mutineer had also mentioned the C.L.C. Briefly.

This is the link with the lesser known serious scholar and author SHIRLEY FREY from:

Texas Published in 2009.

https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.612.6483&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Quite definitive in many ways really…

I hope their graves can finally be properly marked and honoured in the 3rd Decade of the 21st Century!

Hello,

I have recently discovered that my Grandfather was posted to the Chinese Labour Corps Depot in July 1919 . He was in The Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry 1/5th Batallion.

Does anyone know what his role here might have been?

Thank you

Jane

Hi,

Ive just found out that my Grandfather also helped repatriate the CLC back home, starting 16.9.2019 . He was in the 6th Wiltshire regiment.