In January 1942, after the US had entered the war, a large number of American servicemen (known as GIs) were shipped to Britain. Over the next three years approximately 3 million GIs passed through the country, of which approximately 8% were African-American.

From the moment the British government knew that US troops would be arriving, there was concern in official circles about the consequences of the presence of black GIs, not least a fear around the potential for mixed-race relationships and children. Home Secretary Herbert Morrison, for example, was anxious that ‘the procreation of half-caste children’ would create ‘a difficult social problem’[ref]PREM 4/26/9[/ref].

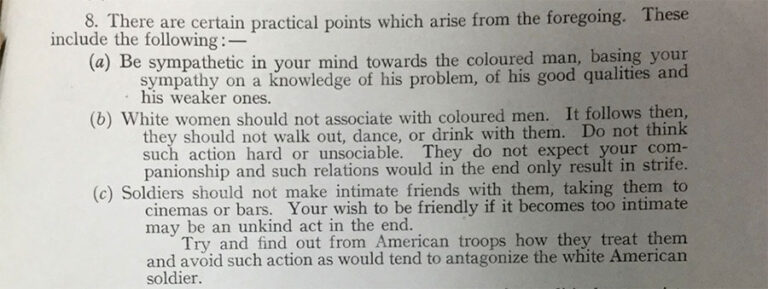

To avoid the birth of such ‘half-caste children’ – as official documents labelled this group – the government was keen to discourage the mixing of black troops and local women. It was proposed that ‘white women should not associate with coloured men. It follows then, they should not walk out, dance, or drink with them’.

These and other government suggestions were collated under the heading, typed in red ink: ‘MOST SECRET’ and ‘TO BE KEPT UNDER LOCK AND KEY’, primarily out of concern that aligning themselves with American policies of racial segregation would cause outrage throughout Britain’s colonies, where millions of black and Asian men and women were fighting on Britain’s behalf [ref]PREM 4/26/9, September 1942[/ref]. The War Office decreed that the British Army should lecture their troops, including the women of the Auxiliary Territorial Service, on the need to keep contact with black GIs to a minimum[ref]PREM 4/26/9[/ref].

In contrast, attitudes of the British public toward the black troops were initially very favourable. Reports from the Home Intelligence Unit (set up in November 1939 to monitor British morale) frequently mentioned people’s appreciation of ‘the extremely pleasing manners of the coloured troops’[ref]e.g. INF 1/292, Home Intelligence Weekly Report, 23 July, 1942; 13 August 1942; 19 August 1942[/ref]. However, when British women started having relationships with black GIs there was voiced disapproval, with the Home Intelligence Report in August 1942 noting: ‘adverse comment is reported over girls who “walk out” with coloured troops’[ref]INF 1/292 Home Intelligence Weekly Report, 19 August 1942[/ref].

If women in relationships with black GIs went on to have children, they generally faced a barrage of criticism. By October 1943 the Home Intelligence Unit was noting people’s rising concern about ‘the growing number of illegitimate babies, many of coloured men’[ref]INF 1/292, Home Intelligence Weekly Report, 28 October 1943[/ref].

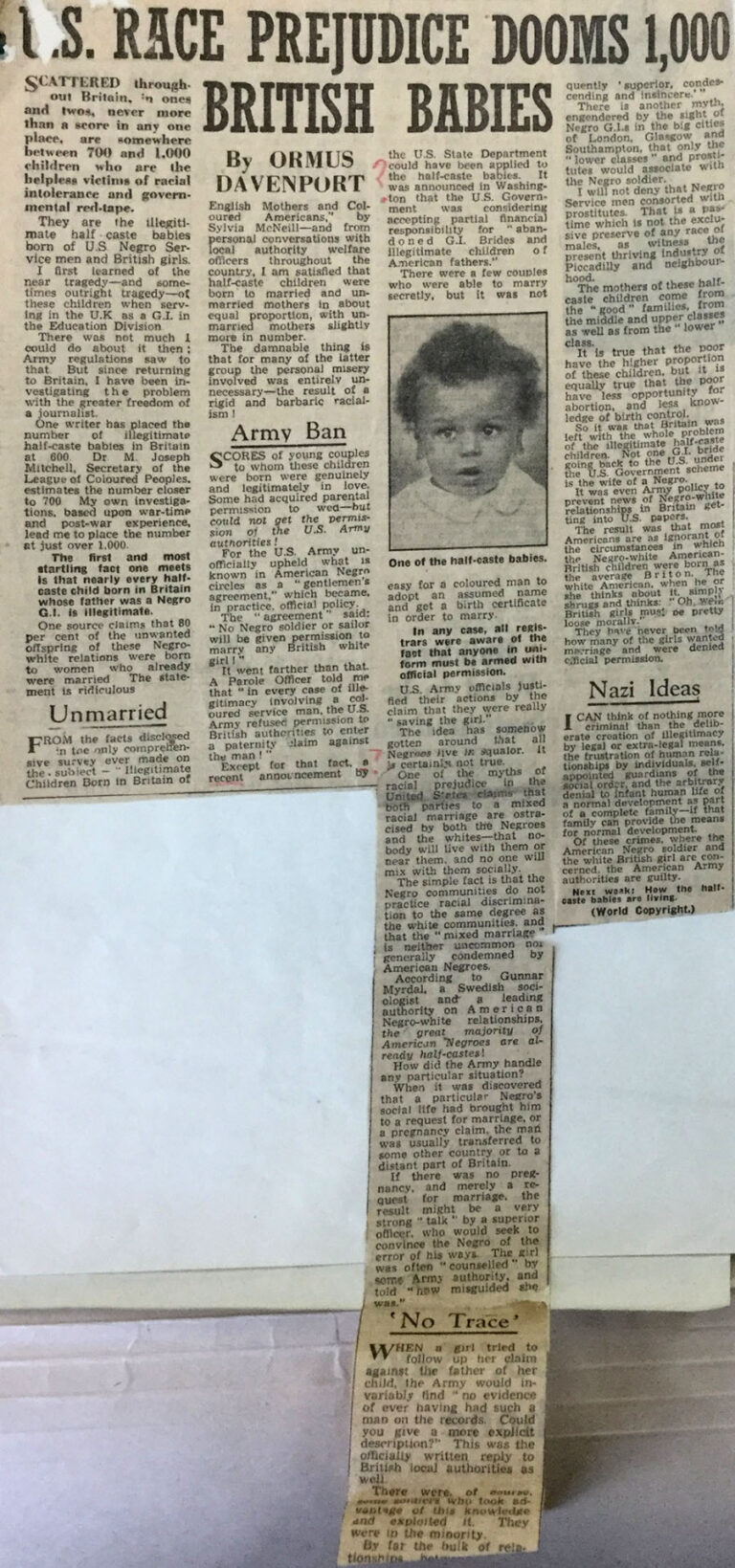

It is estimated that approximately 2,000 ‘brown babies’ were born in Britain during the war and nearly all of them were illegitimate. (‘Brown babies’ was the term given to these children by the African-American press). Every American serviceman had to receive permission to marry from his commanding officer (who in the UK were nearly all white) and avoidance of this permission was a court-martial offence. But for a black GI wanting to marry a white British woman, permission was invariably refused. According to black former GI Ormus Davenport, writing after the war, the US Army ‘unofficially had a “gentleman’s agreement” which became in practice official policy. The agreement said “No negro soldier or sailor will be given permission to marry any British white girl!”… Not one GI bride going back to the US under the US government scheme is the wife of a Negro’[ref]Ormus Davenport, ‘U.S. Prejudice dooms 1,000 British Babies,’ Reynolds’s News, 9 February 1947[/ref].

Nearly half of these babies were given up to local authorities or children’s homes, such were the difficulties and pressures facing the mothers: the stigma of having an illegitimate and ‘coloured’ child, and the fact that between a third and a half of the mothers were already married.

Many such babies born in Somerset were taken in by the local council and placed in a temporary nursery called Holnicote House, a National Trust property that had been requisitioned during the war by the council. Mothers who relinquished their babies hoped that they would be adopted, but adoption societies were loath to take black or mixed-race children, deeming them ‘too hard to place.’ Given difficulties in finding adopters for these children in Britain, Somerset Superintendent Health Visitor Celia Bangham was keen to arrange their adoption by their putative fathers, near relatives or other ‘coloured’ families in the US.

On 13 December 1945, the Home Secretary, James Chuter Ede, met with Miss Bangham and Victor Collins, MP for Taunton, to discuss the US adoption possibility. Chuter Ede was unenthusiastic: he worried about ‘the appalling discrimination made in many parts of the US against coloured people’. He also explained the legal position on adoption: under British law (the 1939 Adoption Act) children were only allowed to be sent abroad to live with British subjects or relatives. African-American couples who came forward to adopt were thus excluded from consideration, and since they were only deemed ‘putative’ fathers (there was no DNA testing for paternity until the 1960s), the black GIs were not considered to be relatives[ref]FO 371/51617, AN3/3/45, W.M.G. ‘Coloured Children of English Mothers and Negro Members of the United States Forces’, 14 December 1945[/ref].

By December 1947 however, the Home Office and the Foreign Office had agreed to allow some children to be adopted in the US. The policy applied to ‘coloured’ children only, according to the Foreign Office, since white children were ‘an entirely different problem’[ref]FO 371/ AN3949/13/45, J E Jackson, Foreign Office, to B Lyon, Home Office, 16 December 1947[/ref].

In what way they were ‘an entirely different problem’ was not spelt out. However the Home Office became worried about this overt exclusion of white children: there was ‘the need to avoid any suggestion that we in this country are trying to get rid of the coloured waifs left behind by the American occupation’[ref]FO 371/ AN4342/13/45, Home Office to Foreign Office, 24 December 1947[/ref].

Yet getting ‘rid of the coloured waifs’ appears to be precisely what they were intending. Adoption by Americans was thus possible in 1948 but the border closed again in 1949, an official statement of explanation stating: ‘any implication that there is not a place in this country for coloured children who have not a normal life would cause controversy and give offense in some quarters.’

Documents from The National Archives have been invaluable in helping piece together this overlooked piece of history in the British experience of the Second World War. However, being official accounts, they portray a very specific perspective.

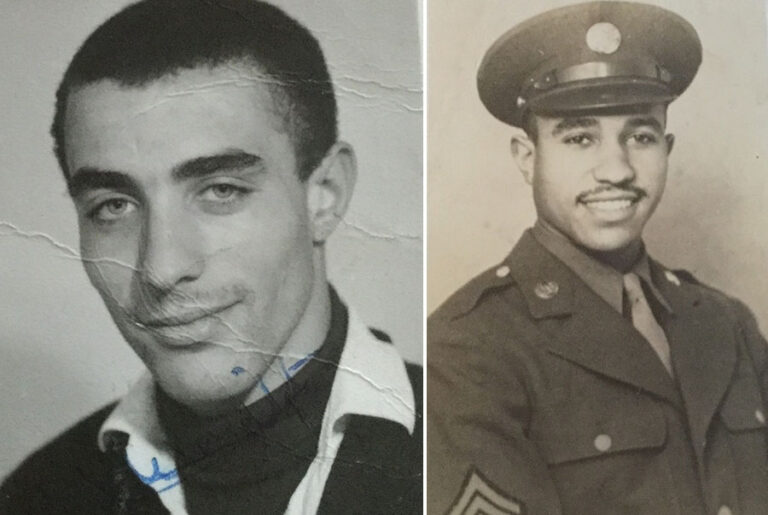

In order to understand the richer history, Professor Lucy Bland undertook interviews with many of these children, now in their seventies. The 60 accounts that she gathered together remind us that behind the government documents, newspaper articles and ‘outsider’ accounts through which what little history of the ‘Brown Babies’ has traditionally been told, are real people. The narratives reveal the ways in which so many of the children and their mothers, fathers and extended families experienced very painful and long-lasting personal, familial and emotional consequences due to the way how their mixed-race relationships and identities were perceived by those around them.

I stuck out like a sore thumb. I was just a reminder I suppose of what mum had done.

Yet also contained in their accounts are episodes and incidents of kindness and acceptance, alongside ongoing attitudes of perseverance and resilience.

[He said] ‘You’re my son aren’t you?’ I said, ‘Yeah.’… We got in the car and he said, ‘Are you gonna kill me?’… And I looked at him. And I just cried … And so did he. We just cried. It was … wonderful … I’d never cried.

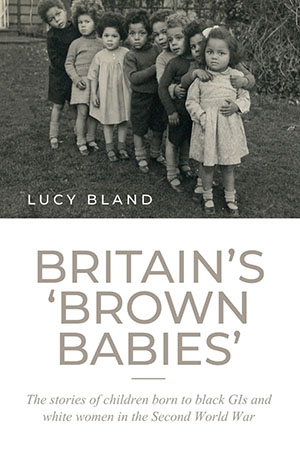

These fascinating and moving stories form the heart of Lucy’s book Britain’s ‘Brown Babies’: The stories of children born to black GIs and white women in the Second World War (MUP, 2019) as well as a current digital exhibition curated in collaboration with The Mixed Museum.

Both the book and the exhibition highlight the diversity and complexity of experience contained within the ‘Brown Babies’ history, alongside the way in which this history is rooted in a wider, long-standing history of the black and mixed-race presence in Britain itself.

To learn more, visit the ‘Brown Babies’ digital exhibition where you can contribute by sharing your reflections in the survey and creating digital postcards, or by sharing any personal history connected to racial mixing in wartime Britain in the exhibition’s community archive: www.mixedmuseum.org.uk/brown-babies.

Article written by Lucy Bland, Professor of Social and Cultural History at Anglia Ruskin University, and Dr Chamion Caballero, Director of The Mixed Museum.

An interesting post as always.

Are there corresponding documents relating to children born of black fathers from African and Caribbean countries that were serving in the British armed forces and based in the UK.

Obviously a much, much smaller sample to draw on but interesting none the less.

A very interesting account about the “Brown” children. Very sad in many ways – the children should not have been made to suffer.

Thank you for this post. I am President of the World War II Era Preservation Society, in the United States. I will be adding this little known piece of history into our displays and talks.

Interesting information . Does it serve a purpose ? it happened ..( in fact it happened all over the world with armed forces and with different countries ..and still does ).

Is it brought up for interest or to point the finger ?–with a 2021 hat on– at the way the UK behaved 70 years ago and say it was wrong ? Tell history as it is but don’t criticise other generations– it was what it was .It was NOT 2021

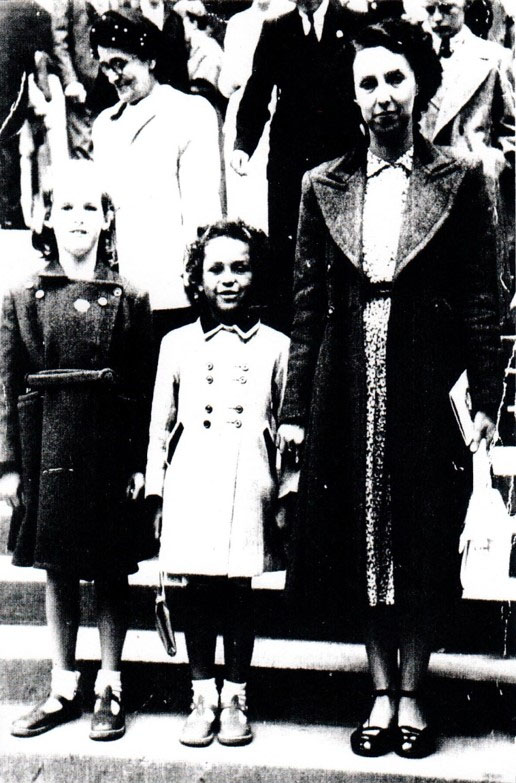

I would just like to say that being born in 1947 and going to school I had a lovely friend at now 73 and looking back to photos of my early life I had not realised that my best friend was black, until I saw a picture my mum had taken back in 1952 of us coming out of school. Children do not see colour and all that stuff. She was my best friend and that was that. I wish I could see her now and share our early days. Her mum must have been very brave as she lived a few door away from me. Credit to my family and neighbours nobody ever said a word . Fond memories. This article has motivated me to find her if she is still alive before it is too late.

I think it’s really important to acknowledge our history and to show how things really were, otherwise we never really learn. In answer to Ken’s question, I think we need to know the truth. How can we understand what goes on today, if we don’t see the forces in play in the past? I would like to hope that we are moving on in terms of how we treat everyone in this country, but that doesn’t happen if we pretend these things never happened. If I had been one of these children or a mother left behind I wouldn’t want to have been treated this way. I don’t want to be a part of doing it to anyone else. This is still within human lifetimes and has affected families. Furthermore insight into the decisions and machinations behind the scenes also help us understand how say a Windrush scandal can happen now.

How very true Jennifer, children don’t see skin colour. I remember having just very few friends in Secondary school in the late 60’s as i was from a different location & didn’t really fit it. Two girls in particular were very kind to me when the others were horrid & taunted me no end. The friends i made, one had red hair & was always picked on too for being red headed & the other was a black girl who was very kind to me but she was also tormented for her skin colour!! To me they were just very kind girls who helped me get through a very hard school day.

Hello Ken: You make some interesting points.

I certainly wasn’t wasn’t ‘pointing a finger’ – with or without a ‘2021 hat on’ – and I suspect neither the author of the post nor those who chose to comment are doing it either.

You are right – it IS interesting and ‘it happened all over the world with armed forces and with different countries ..and still do’.

Your comment ‘Tell history as it is but don’t criticis other generations– it was what it was .’ is good advice when looking back at history.

There’s plenty of situations that we can and should apply your dictum to – the execution of traumatised First World War soldiers and the labelling of Second World War mentally and physically exhausted aircrew as ‘LMF’ are two examples that spring to mind.

I believe that the post is doing exactly what you suggest. It is factual and the only judgement (by today’s standards) terms are those from official documents written at the time.

What purpose does it serve?

That’s an easy one!

It descibes a historical event and official responses to it.

But judging the comments attached to this post, it enables people to share their own experiences.

Records may be historic but people make history.

I have this year traced the the father of my cousin who is a GI baby from WW2 he father was African American

In response to the first comment, it might be worth consulting The National Archives’ research guides on Black British social and political history as well as Children’s homes for guidance on where to find relevant records:

https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/black-british-social-and-political-history-in-the-20th-century/

https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/children-care/

In addition to the very insightful responses to Ken’s post, it might also be worth stressing that there’s always been anti-racist and broader social justice struggles. People have never thought as a homogenous bloc, and anti-racism or a concern with the histories of marginalised groups did not suddenly emerge in 2021. To assume the authors are wearing a “2021 hat” negates this long history, not to mention presents an ethnocentric viewpoint that denies people of colour a voice (unless the assumption is that they have until 2021 been without agency and complicit in their own oppression).

It might also be an interesting exercise to invert some of the questions asked: Is our response to writing about mainstreamed histories – that often exclude people of colour – to ask whether they’ve been brought up “to point the finger?” Do we attempt to diminish their significance (and compound the discrimination faced by the people involved – many of whom are still alive) by attempting to point out that such things were happening elsewhere or have always happened (even when the social conditions underlying them are completely unique)? If we can’t “criticise other generations” then can we not for instance criticise the Nazis, and how are we supposed to learn from the past and create a better world for future generations?

It’s important to note that such questions/statements (often aimed to attempt to delegitimise extremely important and rigorous research into the lives and struggles of marginalised groups – even when carried out by leading academics) are often asked of the histories of minority ethnic groups but not mainstreamed histories, and a more pertinent question might be, why is this?

Ken’s attitude is exactly the reason why these stories must continue to be told factually and accurately, without whitewashing.

There is no denying that there is still anti-blackness in British society today (like in many other western cultures). Think of the outcry, in Dec 2020, against a Christmas advert that featured an entirely black family.

These attitudes are underpinned by decade-old beliefs and traditions that people like Ken prefer not to be spoken about. Leaving these truths unchallenged or unexposed perpetrates the false dominance hierarchy in today’s societies, based on race, and the pretentious moral purity of white people. Some people should si

Thank you Kevin for the references to my question about document sources.

I wonder why Ken bothers to read history, if he doesn’t feel that he should judge what people did then. I hope that I may judge the Japanese who captured my uncle Jack, and put him in a POW camp in Thailand, where he died in 1944.

It was very interesting to read about the GI babies of WW2. A lot of it broke my heart that innocent children could be subjected to such cruelty. However there was an overwhelming sense of joy to know some of the children, be it a small minority were able to be reunited with their paternal fathers.

The frustration that the WW2 GI generation must of gone through and felt is indescribable, at a time where you were all meant to be on the same side fighting for the same cause and yet could be so easily divided through ignorance, segregation and division and racism. This is sad and shocking and we must all respect each other and respect life! It’s too precious to be ignored!

I have only recently discovered that I have a brother born in these circumstances. I along with my siblings feel a devastating sadness that our loving mother should have gone through the anguish she would have faced during this time and to have to part with her baby which must have been agony for her.

I now understand the underlying sadness she carried with her and the guilt she must have felt throughout her life and which she took to her grave.

I only wish we had had this knowledge of our secret brother much earlier .We have all missed out on the relationships we should have had.

In response to Ken: I am the daughter of one of these “Brown Babies”. Injustices like this did happen everywhere, and they do deserve more than a mention. We are not just a note in the history books, we are living humans who until recently, when Lucy researched and made this information public knowledge, have been denied our history. My mother has spent years in and out of therapy trying to undo the damage that happened in her childhood without knowing why. This information has helped bring healing and peace to her, myself and my children. The legacy rattles on.

What a story and I can relate as I was a GI baby born during the 1950’s to an African-American father and white English mother. I even spent some time in a children’s home. I met my father many years later after me and my mother moved to the states. In my home town of Ipswich there was a couple of American air-force bases outside of the town. My upbringing was similar to these children and part of me is sad that children have to suffer because of it. Eventually my mother married a GI and that’s how I came to the states. My age is 68 and looking back I feel very blessed and grateful to God, my mother, my adopted father and my real father who did not regret me when we first met and he stated that he loved me…..

I have recently helped reunite a lady of mixed race, called Margaret who was born in 1942, with her two half sisters born in 1944 and 1951. Margaret was put into care aged about 7, in 1949.

It’s both fascinating and tragic hearing how Margaret was separated from her mother and sisters due to assorted reasons but predominantly due to racism.

Fortunately the sisters are reunited and with the changes in attitude, skin colour is no longer of consequence. I’m so glad that attitudes are changing but they still have a long way to go.

It is very interesting to see that all the stories and cases are just in the South, when up Yorkshire had many Black troops at different times. Why such difference?

My husband is one of these “brown babies” not knowing who his father was for over 74 years, always carrying the burden of uncertainty of just who he was. Thankfully, due to DNA he discovered his American family, sadly his father had passed away years before. But the relief it gave him to know who he was, was tremendous and he now has new family which is wonderful.

I just wonder though if anyone has managed to get their deceased fathers name put onto their birth certificate?

Please may I quote your article in a novel I am writing set in this time period in Somerset?

I would much appreciate it.

I have written other books, my website is http://www.lynbehan.com

Thank you

I was born in Northern Ireland my father was an American black gi soldier my mother was white I was born in 1945 never found out who my father was I’m now 80 years old and would like to know his name before I die my be this is long shot I have got name now should I try and find relatives or just leave it