Arabic. Beautiful, poetic, terribly useful, and awfully difficult to learn. In the 1940s, the British Army must have shared my opinion: they set up a special school to teach Arabic to academically inclined young officers.

The Middle East Centre for Arab Studies (MECAS) was quickly nicknamed ‘the British spy school’ in the Middle East – was it more than a mere language training centre?

MECAS in Shemlan, Lebanon (catalogue reference: FO 371/157595)

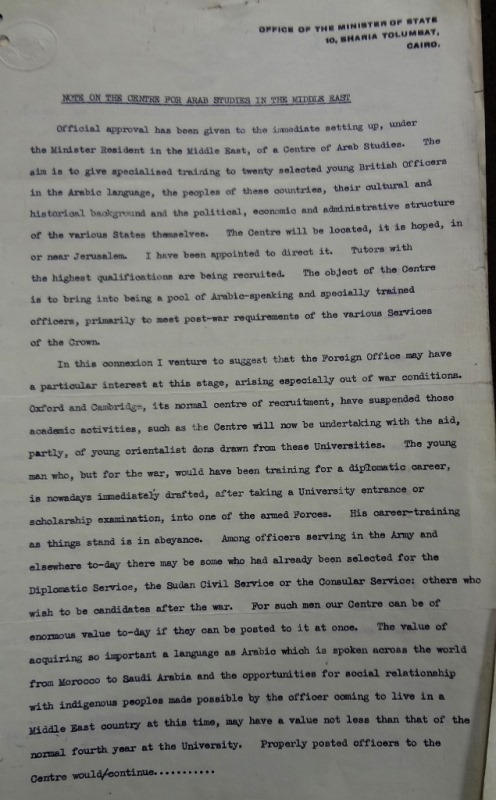

Note on the Centre for Arab Studies in the Middle East (catalogue reference: FO 366/1348)

During the Second World War, there was a pressing need for Arabic speakers. The idea of setting up an Arab Centre ‘to bring into being a pool of Arabic-speaking and specially trained officers, primarily to meet post-war requirements of the various services of the Crown’ first emerged in 1941.

It really started being discussed in 1943, when Arabist and explorer Bertram Thomas sent a ‘Note on the Centre for Arab Studies in the Middle East’ to London. The aim of such a centre, he wrote, was

‘to give specialised training to twenty selected young British officers in the Arabic language, the peoples of these countries, their cultural and historical backgrounds and the political, economic and administrative structure of the various States themselves’ (FO 366/1348).

All the departments concerned agreed it was a good idea, but they were a bit unsure as to where they would find these 20 young men, especially as Thomas only wanted officers with ‘high educational standard’: ‘it would obviously be detrimental to have second raters,’ he wrote (FO 921/217).

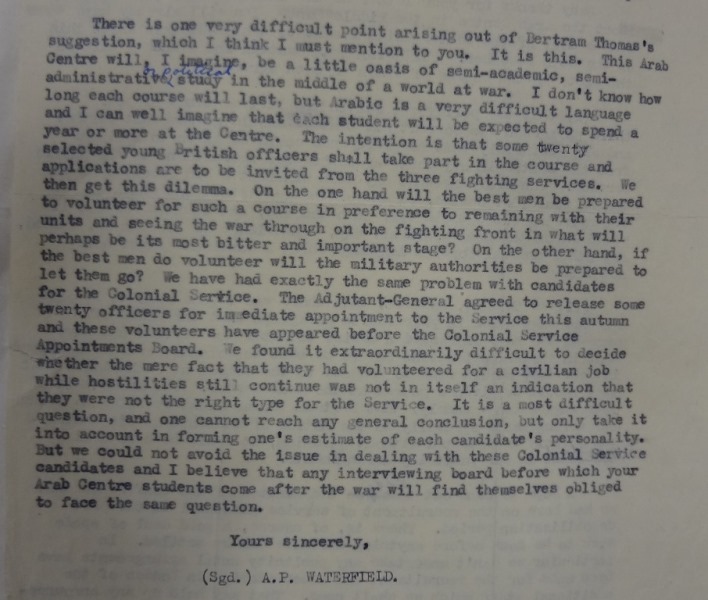

It wasn’t going to be easy to recruit suitable students at a time when they were required for operational duty. Waterfield, from the Civil Service Commission, summed it up perfectly:

‘there is one very difficult point arising out of Bertram Thomas’ suggestion (…). This Arab Centre will, I imagine, be a little oasis of semi-academic, semi-administrative or political study in the middle of a world at war’ (FO 366/1348).

Waterfield to Wilcox, 23 December 1943 (catalogue reference: FO 366/1348)

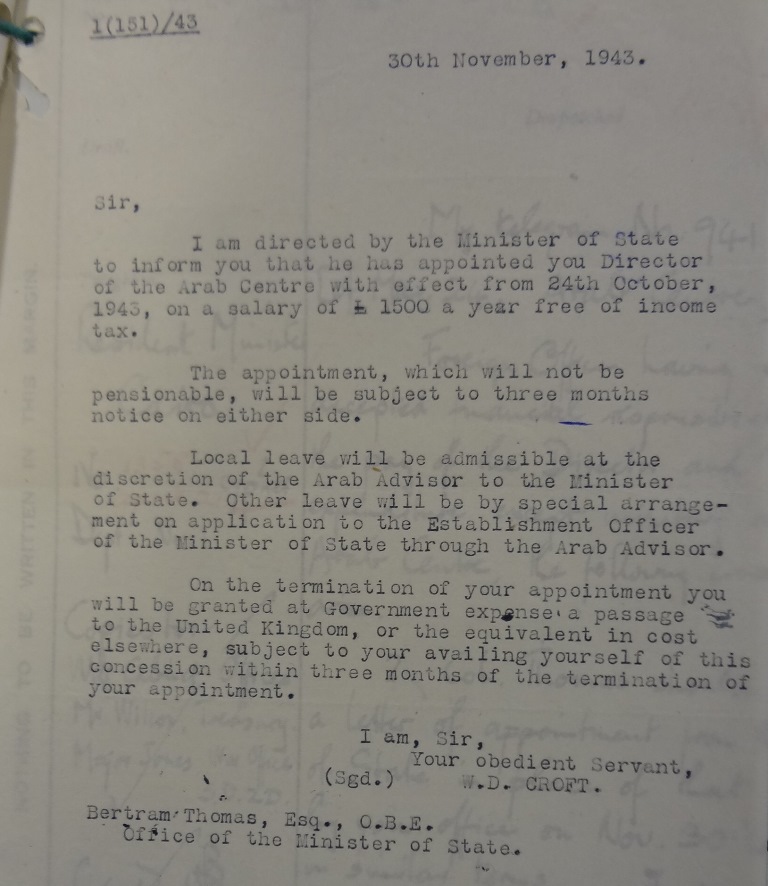

The plan was approved in principle by the Chancellor of the Exchequer and, after much correspondence, Treasury agreed as well. The centre was to be paid for by the Foreign Office (except for the pay of military personnel), and was to be a war measure in the first instance (CAB 21/1001). On 30 November 1943, Bertram Thomas was appointed as Director (FO 371/40002).

Bertram Thomas’ appointment, 30 November 1943 (catalogue reference: FO 371/40002)

The difficult question of the location of the centre remained to be solved. The matter was of particular importance as it would determine the dialect the students would learn. The centre also had to be easily accessible for visiting lecturers. Bertram Thomas ruled out Iraq (unsuitable climate and atmosphere) and Cairo (too many distractions); he favoured Damascus, which would apparently offer ‘better Arabic’, Beirut, or Palestine. Syria and Lebanon were almost instantly rejected as it would have created problems with the French, leaving Palestine or Transjordan as possible options (FO 226/247).

The Colonial Office, however, ‘strongly opposed’ the idea of setting up an ‘Arab Centre’ in Palestine. They were concerned the Zionists may interpret it as a sign of pro-Arab sentiments, especially if it was called ‘Arab Centre’. ‘Its establishment there,’ they commented, ‘would lend itself to serious misinterpretation in the existing political atmosphere of the Middle East’.

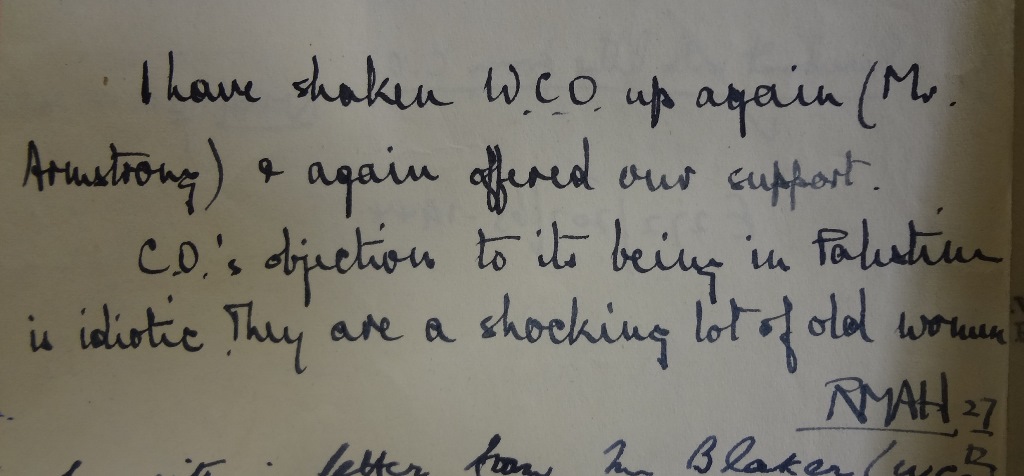

Robert Hankey, in Tehran, noted: ‘CO’s objection to [the centre] being in Palestine is idiotic. They are a shocking lot of old women’ (FO 371/34963).

Minute by Robert Hankey, 27 December 1943 (catalogue reference: FO 371/34963)

The High Commissioner in Palestine was consulted. To the horror of the Colonial Office in London, he went against the party line, declaring he did not ‘attach any real weight’ to the political objections and that he saw ‘no objection to the location of the Centre in Palestine and to it being called Arab Centre’ (CO 732/88/23).

It was decided the new centre would be set up in Jerusalem and would be called ‘Middle East Centre of Arab Studies’. The old Austrian hospice was requisitioned from 15 May 1944 (FO 921/217), and the Centre finally opened in June (FO 921/218).

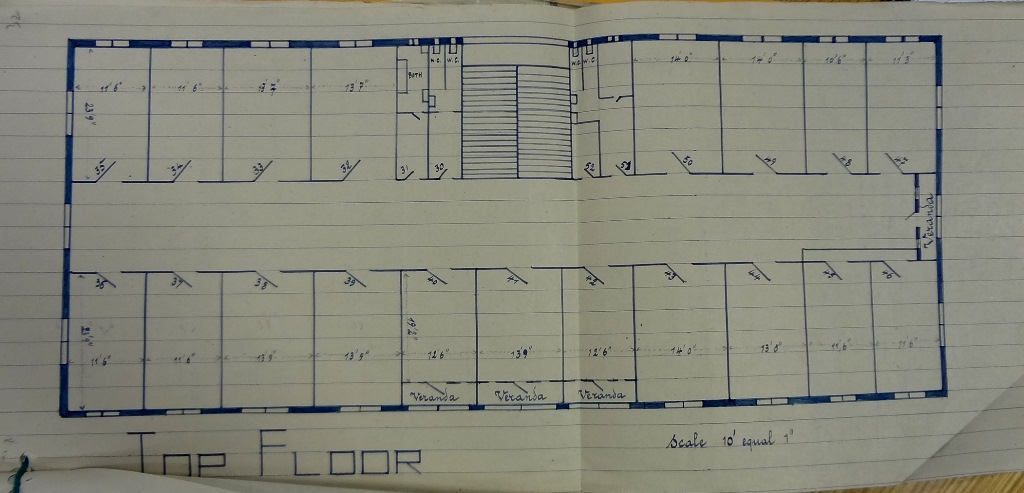

Plan of MECAS in the Austrian Hospice, 1946 (catalogue reference: FO 366/1481)

The MECAS method was very specific and extremely demanding. Students would have intensive Arabic language courses every morning. The aim of the centre was to ‘teach Arabic as a language of modern intercourse’ and as ‘many things happen to a language between the grammar book and the street’’, colloquial Arabic was taught as well as written Arabic (CAB 21/1001). The afternoons would be devoted to lectures, exercises and essays. This was more or less effective; some students progressed very quickly, while others, possibly less linguistically gifted, struggled greatly and failed the rather difficult exams (FO 366/1806).

- MECAS exams, 1946 (catalogue reference FO 366/1806)

- MECAS exams, 1946 (catalogue reference FO 366/1806)

- MECAS exams, 1946 (catalogue reference FO 366/1806)

At the end of the 1945-46 course MECAS, which had been set up as a war establishment, became a civilian institution (FO 924/528). As such, it had to abide by the general austerity measures, and the Foreign Office had to battle with Treasury, not impressed by the lack of efforts to reduce costs. ‘We think,’ they wrote, ‘that a grim determination on austerity could produce far more handsome savings’. As a result, the number of students rose from 20 to 34, and students from private companies were included to make up numbers and increase revenues (FO 366-1481).

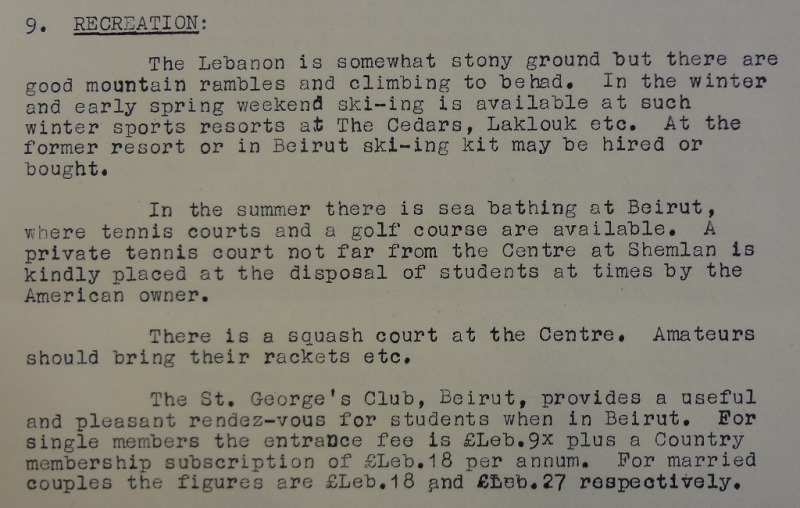

Due to the unstable political situation in Palestine, MECAS was briefly transferred to a tented camp in Zerqa, Transjordan, and then, in October 1947, relocated in an old silk factory in Shemlan, Lebanon. Shemlan, about 20 miles from Beirut, in the mountains, seemed particularly well-suited to the purpose of the Centre: the climate wasn’t too exacting and the students had access to a decent range of entertainment.

Recreation at Shemlan (catalogue reference: CO 877/51/4)

In 1950, the format of the course changed slightly. Students were asked to attend a 10-week preliminary course at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, followed by 10.5 months in Lebanon. This preliminary course, which could only be skipped by those who already had good knowledge of the language, was exacting, but hugely beneficial to the students. According to Brenan, the Director of MECAS at the time, ‘the weaker element also, despite the feeling that they were suffering from indigestion from so much grammar in a short time, unquestionably benefited from the grilling they received in London’ (FO 366/2938).

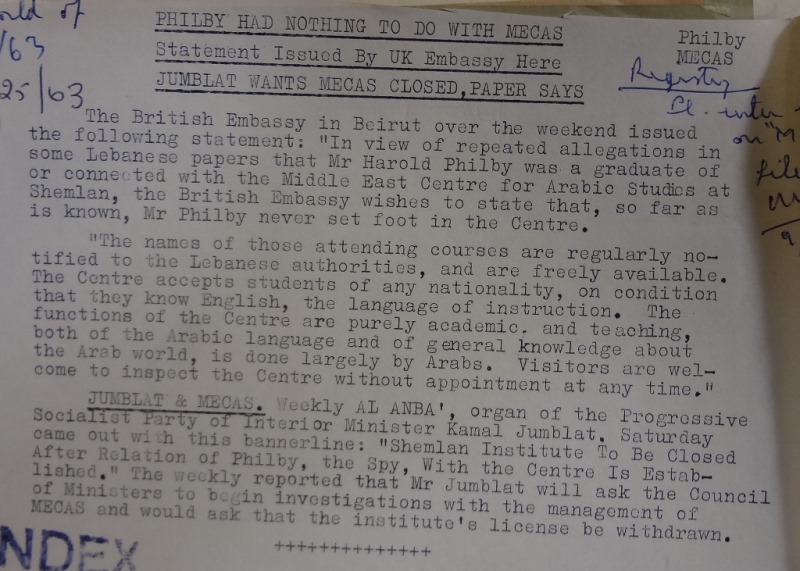

It all seemed to be working pretty well until Kamal Jumblatt became Minister of National Education in Lebanon. He launched a series of attack in the press and in Parliament which looked like a personal vendetta, and vowed he would close down the ‘British spy school’. As an Arabic training centre, MECAS had always had the reputation of being a ‘spy school’, with articles appearing now and then in the Egyptian and Lebanese papers. Criticisms, however, had ‘generally been good-humoured’. From 1961, MECAS was frequently described in the press as ‘the biggest espionage centre in the Near East’, ‘an espionage base’ or ‘a poisonous dagger in the heart of this beloved homeland’ (FO 371/157595).

- Press attacks against MECAS, 1961 (catalogue reference: FO 371/157595)

- Press attacks against MECAS, 1961 (catalogue reference: FO 371/157595)

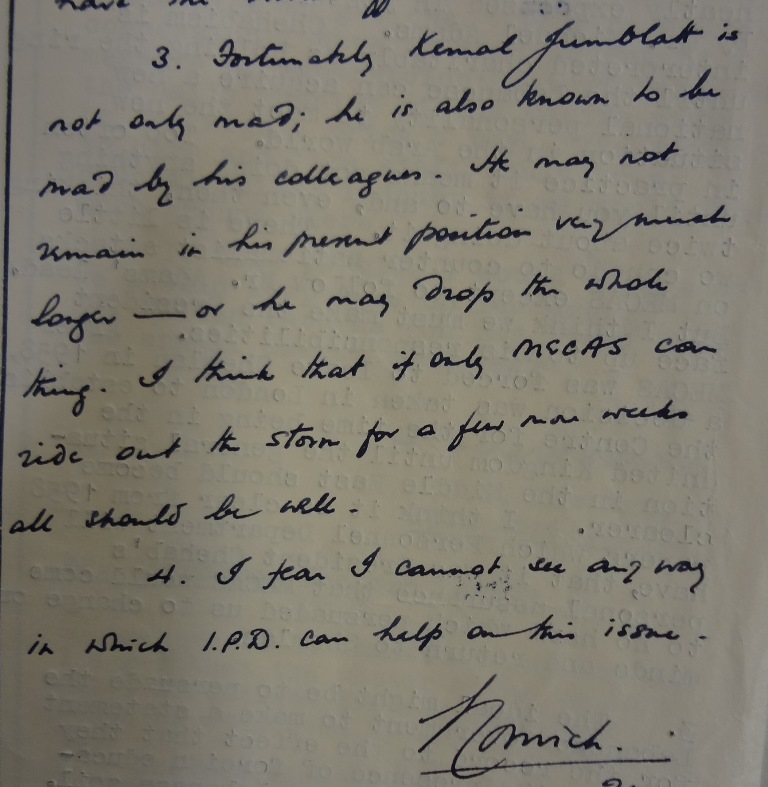

Things escalated after the arrest and confession of George Blake, who had been spying for the Soviet Union and was picked up at Shemlan (CAB 128/35/26). The Director, Wilton, complained of near-harassment, surprise inspections and that Jumblatt was ‘probably beyond the reach of rational argument’. In London, the Foreign Office’s approach was that MECAS enjoyed ‘a measure of presidential protection’, that Jumblatt wouldn’t be minister for ever, and that the attacks would eventually stop. Lord Norwich noted: ‘fortunately, Kemal Jumblatt is not only mad; he is also known to be mad by his colleagues’.

In 1958, when MECAS had returned to Shemlan after having been evacuated briefly due to the crisis between Maronite Christians and Muslims, President Chebab had given personal guarantees that the Centre was welcome in Lebanon. These assurances were repeated and, in August 1961, MECAS was declared perfectly legal by the Ministry of Justice – which prompted Lebanese newspaper Sha’ab to state on its front page: ‘espionage legalised in Lebanon’ (FO 371/157595).

In 1962, when Philby defected to the Soviet Union from Beirut, his name was linked to that of MECAS, and the embassy had to publish a statement formally denying he had ever studied at the Centre. This, however, didn’t help, and in Beirut, Crosthwaite warned that ‘even friendly Arab nationalists [regarded] the presence on Lebanese soil of a specifically Foreign Office institution as a symbol of Britain’s residual imperialist yearning in the Arab world’ (FO 366/3207).

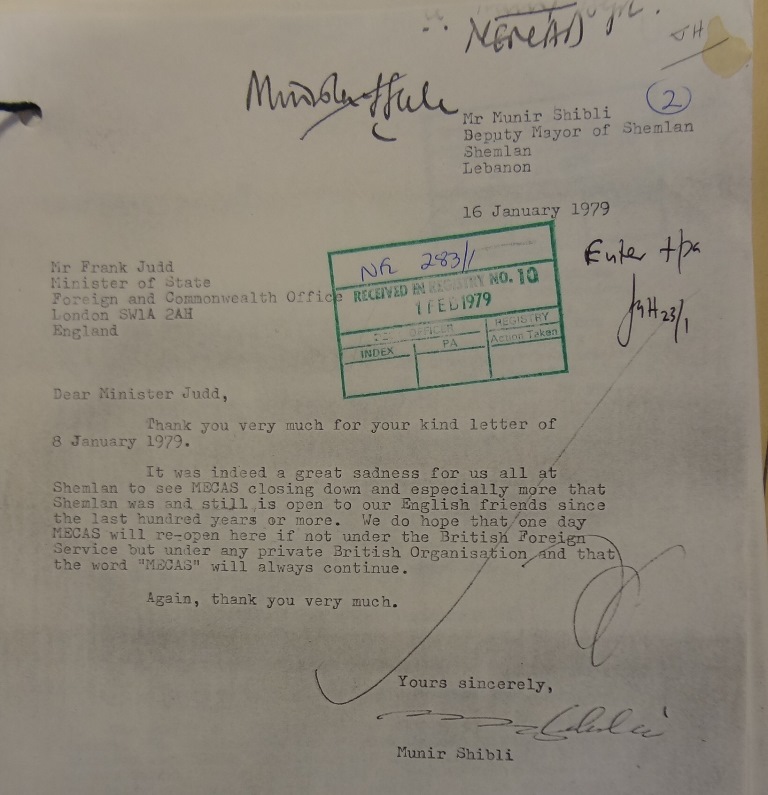

MECAS was eventually closed in 1978, for security rather than political reasons. The civil war was raging, and with Shemlan sitting on a line of Palestinian/Syrian communications, it felt safer to bring it back to London (FCO 93/2019). Some newspapers welcomed the departure of ‘the British Spy School’, but it had been the livelihood of the village for over 30 years. The closure came as a shock to the villagers, who wrote to the Foreign Office and all the former Directors to ask them ‘not to exclude for ever the possibility of MECAS returning to Shemlan’ (FCO 93/1516).

Munir Shibli, Deputy Mayor of Shemlan, to Frank Judd, Minister of State at the FCO, 16 January 1979 (catalogue reference: FCO 93/2019)

MECAS’ objectives and methods have been much debated since. MECAS, some said, was a useless crammer – forcing random lists of words into the head of half-willing students was never going to work; as a result, the Centre produced Arabists ‘with no deeply established understanding of the language and certainly no liking for it’ FCO 93/1516). MECAS, purists added disdainfully, taught a version of Arabic that only MECAS alumni could understand; it was disconnected from reality. MECAS, some (non-Arabic speakers) claimed, created a powerful ‘Arabist mafia’ – in the mid-1990s, the Permanent Undersecretary, the Political Director and the Chief Clerk at the FCO, as well as the Head of MI6 and the Director General of the British Council were all graduates from MECAS.

Most of these criticisms are valid. But a nest of spies? There is no evidence of that. In 1943, a note did mention that ‘the immediate function of the Centre would be to train Army Officers for military and political intelligence’ (FO 371/34960), but this was before MECAS became a civilian institution. In 1951, the Director noticed six army officers had ‘received secret instructions from G.H.Q. M.E.L.F. to collect information of Intelligence nature and report to G.H.Q.’ Outraged, he demanded the instructions should be cancelled and reminded all concerned that the Centre’s activities ‘must be completely above board’ (FO 371/91443).

- Beirut to Foreign Office, 7 July 1951 (catalogue reference: FO 371/91443)

- Instructions cancelled, 8 July 1951 (catalogue reference: FO 371/91443)

It is a bit unfortunate that George Blake was arrested in Shemlan while studying at MECAS, but it may be pointed out that he was a Soviet spy, not a British one. It is just as unfortunate that Philby should have disappeared from Beirut, but as stated by the embassy at the time, he had never studied at MECAS and he was also a Soviet spy.

I can only conclude, in the words Wilton in 1961, that if the Middle East Centre for Arab Studies was indeed a spy school,

‘I am taking the line (with those sophisticated enough to appreciate it) that it is a tremendous testimonial to our efficiency that despite 17 years in the business no graduate of MECAS has ever been caught spying’ (FO 371/157595).

[…] Leave a reply […]

For reference the Treasury file is E46657/1 (T 162/1018/3 ).

Brilliant! Interesting bit of our history in the Middle East. Thanks

My grandfather Alan Charles Trott worked at MECAS in the 50s. How fascinating to find out more. I never knew him but I also have taught languages so I feel a connection is there. Thankyou!

Slightly rearranged second draft…

George Blake was one of my father John Hopkins’ students when he was Principal Instructor at MECAS in 1959, under director Wilton. The spy story only erupted on our return to Britain and came as a complete surprise. My father knew Blake well of course, but recalled him as just an unremarkable student of Arabic. And that was it – there was no dramatic story.

As a six-year-old boy, I was too young to join my elder brothers at boarding school in England, so I went with my parents to Lebanon and spent a glorious and richly memorable year in Shemlan. I used to play with Blake’s son at their house just over the road from the famous Cliff House restaurant. This didn’t happen very often as I spent more time with the two Wilton boys who were close to my age and we shared a governess.

I have vivid and totally favourable memories of Shemlan and its people, despite the apparent political turmoil of the era. We lived in quite a luxurious 3-bedroom first-floor flat in the heart of the village, nestled in the foothills some 700m above Beirut. There was an unforgettable view of the city from our balcony, that twinkled glamorously at night. We had all our meals on the balcony, listening to the World Service, and on a clear day you could peer between the lemon trees and sometimes see Cyprus.

We had a home-help, Rosette, who was married to Munir the village policeman. He had a gun which impressed me enormously, but he never seemed to do anything apart from wander around the village like a classic British Bobby. Rosette didn’t have children and we spent a lot of time together. Her English was about as good as my Arabic but somehow we managed to communicate perfectly well. She would cook my favourite meal of courgettes stuffed with rice and mince. Rosette was a wonderful lady.

I had complete freedom of the village and was always met with friendliness by the locals – and their dogs. They also roamed free, visiting any house where there might be scraps of food. Two dogs in particular found a welcome at our flat and became pretty much resident. We named them Max and Desmond, both handsome Pointers – hunting dogs, with a gentle nature and silky ears. Every man in the village seemed to have a shotgun and they would frequently loose-off at any small bird among the olive groves, which were then strung around their belts for the pot. A gruesome sight, but apparently a delicacy.

My parents made the most of their spare time, swimming in the Med, skiing at The Cedars, with trips to Damascus, Jerusalem and Baalbek, stopping off at numerous other cultural hot-spots along the way. Unfortunately I was too young to really appreciate much of that, other than in hindsight.

My brother Simon Hopkins has followed in our father’s footsteps. Until his recent retirement, he was Professor of Arabic at Jerusalem University.

Hi, here are a couple more snippets I thought might be of interest. If you agree, perhaps you would insert the first piece as a new third paragraph? And add the trivia item at the bottom? Many thanks and best regards, Richard Hopkins

The MECAS building was an impressive sight – big, stylishly modern and gleaming white, standing alone on a lofty vantage point above the main road. It was unmissable and no doubt made a strong statement about Britain. The Director’s house was more of the same, set apart from the main building (it’s concealed behind the main building in the first photograph shown here).

MECAS trivia

Several ex-MECAS students stayed in touch with my parents, many having risen to high status in the Foreign Office and international business. I bumped into one of them recently and he told me that Amal Alamuddin’s family had some connection with MECAS, owning the land or something? Amal is married to George Clooney.

My father, William Paterson, joined the Foreign Office after the war. After the war the Foreign Office policy was to start admitting a wider intake of recruits other than from Oxbridge. My father was a graduate of Glasgow University. My father’s first posting was to Beirut under the then Ambassador Housten-Boswell. He studied at Shemlan in the 1940’s and I was born in Beirut at that time.

My father went to MECAS in 1957. He was employed by Kuwait Oil Co. We first lived for three months in the St George Hotel on the Corniche, and the latter three months in the village, in a house that sounds remarkably like Richard Hopkins. The locals use to sit out underneath our balcony chatting, smoking shish and drinking coffee. We commuted to school in Beirut attached to the American School. My Dad contributed to the MECAS memoirs published by Stacey Intntl.

Is there a list of those who were posted to MECAS in the 1960s?

Hello,

Is there any record on the acquired land for MECAS in Shemlan and the new building ? Who was the architect?

My late father Lt Col Kingston St Barbe Adams was at MECAS in 1955/56 he studied Arabic and went on to work in Saudi Arabia, Oman, Dubai and Libya for much of his pre war working life.

I was born in Beirut in 1956.

I was a student at MECAS in early 1975 and watched the smoke rising over Beirut Airport – a sad harbinger of the next 50 years. I went to Riyadh next and whatever the purist criticisms of the Shemlan accent were perceived to be by others, the Saudis seemed terribly impressed by the Al Fusha variation forced upon us there.

Worked for me anyway!

PLEASE NOTE: Due to the age of this blog, no new comments will be published on it. To ask questions relating to family history or historical research, please use our live chat or online form. We hope you might also find our research guides helpful.