As part of my ten-week placement at The National Archives for my MA in Public History at St Mary’s University, Twickenham, I searched for a topic that would make a compelling blog post.

This topic has come in the form of the unusual story of a relatively unknown pirate. Indeed, his story is unique in terms of piracy of the early 18th century and gives budding researchers, such as myself, a good introduction as to how one might locate, explore and revive a story that has long been buried at The National Archives.

Career change

The early life of Bridstock Weaver is mostly unknown, but we can assume that he was one of many who saw opportunity in the increasing trade that flowed between Britain and its colonies. Weaver was, at the time of his capture, the first mate of the trading vessel Mary and Martha of Bristol. Reportedly at anchor off the island of St Christopher, Weaver recounts seeing an approaching vessel under English colours. Investigating via a long boat, Weaver approached the vessel and was set upon by a group of pirates.[ref]1. HCA 1/55, no.53[/ref]

The ship with which Weaver had the unfortunate encounter was the Royal Fortune, one of many in Bartholomew Roberts’ growing fleet. Roberts was the infamous and arguably most successful pirate of the ‘Golden Age’ of piracy, at least in terms of vessels captured: some credit him with over 400 captured.[ref]2. Ed Fox, Pirates In Their Own Words: Eye-witness Accounts of the ‘Golden Age’ of Piracy, 1690-1728 (Raleigh: Lulu Press, 2014), See 23.[/ref]

Realising the true nature of the ship too late, Weaver and the others found themselves with pistols pointed at them. Forced aboard and with pistols ‘aimed at their breasts’ they were forced to sign the pirate’s articles. Otherwise known as the pirate code, this was a set of laws to which pirates must adhere. There were slightly different versions but the core themes were the same.

The Mary and Martha, still unaware of the true nature of the Royal Fortune, was set upon, plundered, burnt and left adrift with the remaining crew taken prisoner. The Royal Fortune then disappeared to an undisclosed safe harbour in the West Indies.[ref]3. HCA 1/55, no.53[/ref]

Years as a pirate

Weaver spent the majority of the next three years engaged in piracy. In his examination during his trial in London, Weaver admits aiding in the targeting of several sloops (a ship design dating from the 17th century, favoured for ease of handling and ability to sail upwind), other vessels and even a brigantine (bigger than a sloop, but considered to have superior manoeuvrability and speed).[ref]4. HCA 1/55, no.53[/ref]

However, the true nature of Weaver’s activates as a pirate was likely far greater in scale than he explained during his trial. Weaver was actively engaging with his supposed captors, even taking sides in the internal division between Roberts and one of his subordinates, Thomas Anstis.

By 1721, Anstis – along with Weaver and others – broke off quietly from Roberts. Weaver was later trusted enough to be made captain of the Good Fortune, which had been commandeered by Anstis when leaving Roberts. Anstis took the newly-captured Morning Star as his own ship (however this is disputed).[ref]5. Harold Horwood, Plunder and Pillage: Atlantic Canada’s Brutal and Bloodthirsty Pirates and Privateers (Halifax: Formac Lorimer, 2011), 97.[/ref] Weaver later broke off himself in 1722 and reportedly pillaged over 50 vessels.[ref]6. Philip Goose, The Pirates’ Who’s Who (New York: Burt Franklin, 1924), 316.[/ref]

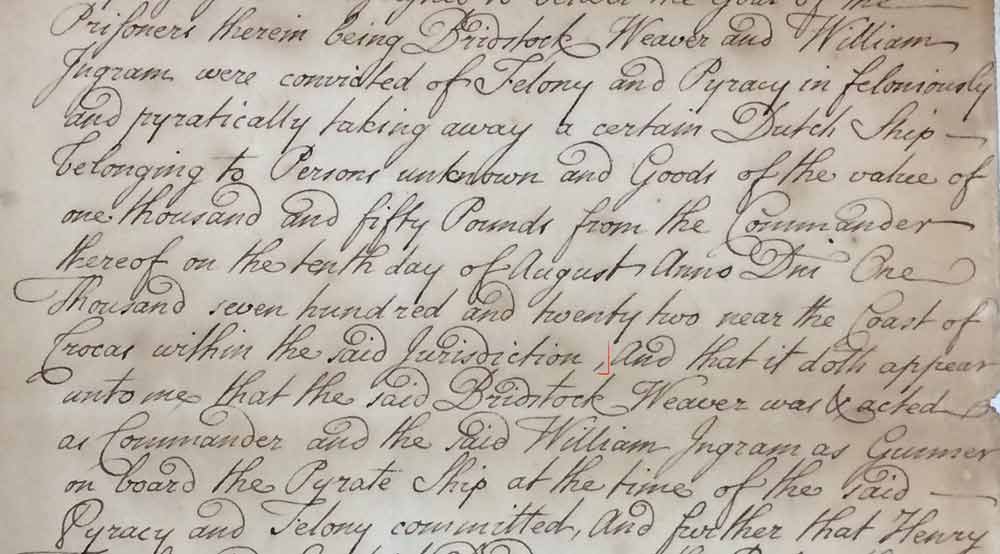

Details and accounts of some of the ships that Weaver targeted, both as part of Anstis’ company and by himself, exist in The National Archives. The Morning Star was a Dutch vessel targeted by Anstis on 10 August 1722. It was taken and plundered of its goods, which were valued at £1,050. [ref]7. T1/258 no.147[/ref]

Extract detailing the capture of the Morning Star and value of its cargo (catalogue reference: T1/258 no.147)

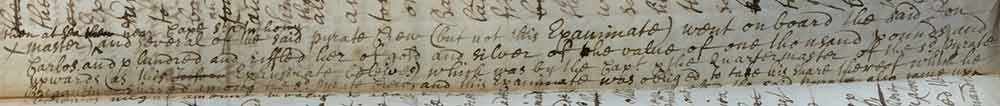

Arguably Weaver’s greatest act of piracy, in terms of the value of cargo looted, comes in his capture of the Don Carlos in 1722, after splitting from Anstis. In William Ingram’s examination at his trial, details of the Don Carlos, a Spanish vessel can be found. Ingram was present during the assault and was ‘forced’ to take his share of the booty. The vessel was successfully attacked and plundered of its cargo of gold and silver.[ref]8. HCA 1/54 no.141[/ref] This is confirmed in a foreign report.[ref]9. HCA 1/30 pt2 no.226[/ref]

Extract detailing the plundering of the Don Carlos and its cargo of gold and silver (catalogue reference: HCA 1/54 no.141)

Booty to bust

Weaver eventually reconnected with Anstis in 1723 and they grouped together once more. Their luck would not hold and both were hunted mercilessly by the Royal Navy, eventually being chased to a small island.

Many of Anstis’s crew were captured but Anstis, Weaver and others fled into the woods. Interestingly, Anstis was later found murdered in the woods, apparently by his disgruntled crew.[ref]10. Horwood. Plunder and Pillage, 97.[/ref] Was Weaver involved in his murder? There is no proof of this, but the potential of this theory is telling of Weaver’s character.

Weaver managed to escape the island via a sloop carrying logwood that was bound for Holland but stopping in Falmouth. Upon reaching England, he travelled by land to Bristol. For the next few months, Weaver operated mostly from Bristol but was briefly imprisoned on various occasions. Later he encountered a captain of a vessel that he had targeted as a pirate. Initially, the encounter was civil: the captain asked only for the return of what had been stolen. Weaver could or would not do this and was apprehended in Bristol and brought to London to be tried.[ref]11. HCA 1/55 no.53[/ref]

A surprising pardon

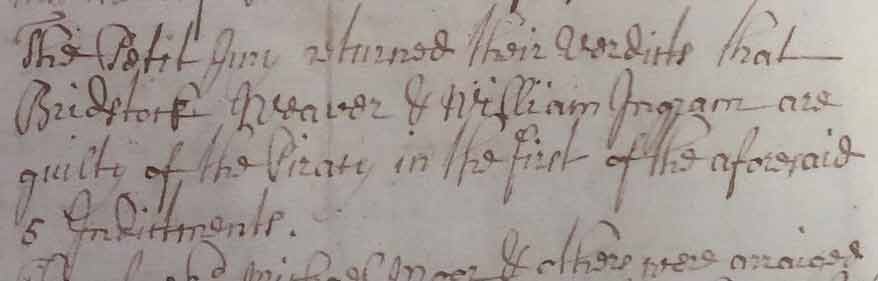

Weaver pleaded not guilty but was ultimately found guilty by a jury and sentenced to death in May 1725.[ref]12. HCA 1/30 pt2 no.227[/ref]

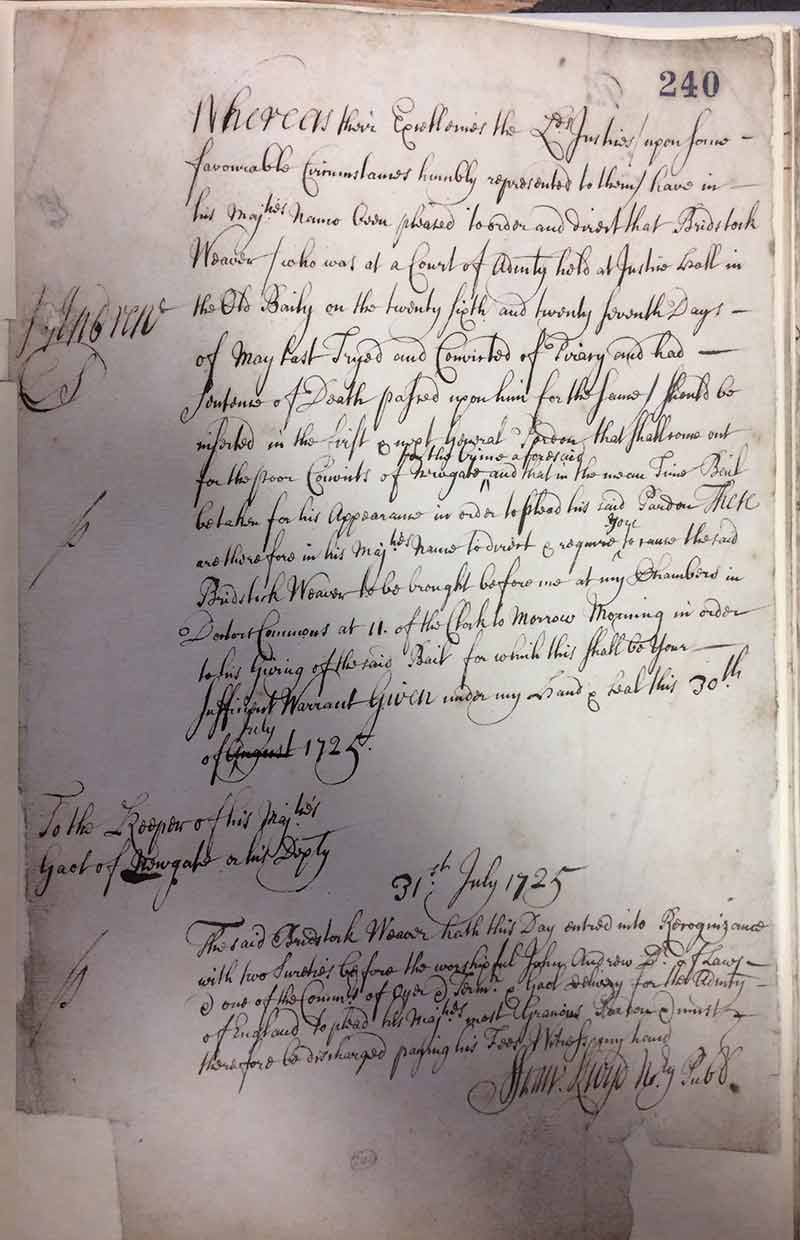

Curiously, by 31 July 1725 Weaver had secured a full pardon from the King.[ref]13. HCA 1/30 pt2 no.240[/ref]

How he did this is unclear – and odd, considering his involvement with Roberts and Anstis. Also his period of acting alone, when he had ample opportunity to return home, was spent preying on vessels, securing his position as a pirate.

With this in mind, his defence was poor and was unlikely the source of his sudden pardon, especially when considering that Ingram (junior to Weaver as a pirate) was executed despite asserting the same defence as Weaver.

From this point, Weaver largely disappears as a figure of interest from the records in The National Archives: a curious end to a murky career as a pirate. Some sources incorrectly state that Weaver was executed.

What researching Bridstock Weaver can teach us

The story of Weaver was pieced together through a number of different sources found in an index of sources for the High Court of Admiralty (HCA). The Admiralty recorded all investigations and trials of pirates and, as a result, many of the sources I used were found in the HCA series. I was directed to these while actively searching for an interesting but obscure piracy case.

However, Weaver is also a good example to show that a wide variety of material may be relevant. For example, information on what was plundered and its value was found in Treasury sources (under reference: T). The indexes offer great potential for any researcher looking for a topic to explore. They contain dozens of stories that have long remained dormant and can offer a starting point to rediscovering a forgotten chapter of the past.

To know what indexes may be of use to your research, you should first make use of Discovery. If you type the subject of your research into Discovery, you will be directed to matches. Make note of the references of those of most use; for example, HCA is the reference for the High Court of Admiralty. Knowing this will provide you with the index that will be of greatest use to you. There is also an option to ‘browse records’, which may be of use to those who wish to see what the archive holds more generally.

Beyond the wider historical lessons that the study of Weaver provides, there are also lessons to be learned in the understanding of 18th century documents. This was often a challenge, one that I’m still working to perfect. The National Archives offers a wider range of material to help introduce researchers to palaeography. I would recommend reviewing these guides to make an immense variety of often daunting material held at The National Archives more accessible.

A ‘presentment’ (tax return) dated 1758 held at Shropshire Archives (ref 552/1/1493) shows a Bridstock Weaver of Hereford as freeholder of five messuages (dwellings) in Skyborry, one of which was caalled the Mansion House. Skyborry is a township in the parish of Llanfair Waterdine, Shropshire, but very close to the town of Knighton the other side of the River Teme in what was then Radnorshire.

Was this the same man?