Nazi bombers flying over British cities dropping not bombs, but bank notes. This may sound like a fantasy, but in fact it formed part of secret German plans to invade Britain. At Hitler’s specific orders the Nazi war machine printed millions of pounds of forged British bank notes and sought to use these as a weapon of war. The extraordinary story of this escapade is documented in files held here at The National Archives.

On 19 October 1944 a German civilian was arrested by troops from the 102nd US Cavalry Reconnaissance Group, trying to cross Allied lines near Wirtzfeld in Belgium. Although carrying a false passport this individual was quickly recognised as Alfred Naujocks, a well known member of German intelligence. He was described by MI5 as ‘a thug of the New Order’ and that his ‘entire life is a grim record of political crime and bullying arrogance’ (KV 2/279). Naujocks was, however, desperate to save his own skin and so proved a treasure trove of information. One of the most extraordinary revelations to come from his interrogation was that he had set up a top secret unit to forge British bank notes on a vast scale.

In early 1940 Naujocks, who was head of a technical bureau in German intelligence, was instructed to develop a factory capable of forging British bank notes. The instructions came from Hitler himself, who wanted to drop huge quantities of forged bank notes from German aircraft. The idea was that the forgeries would be picked up by British civilians and so undermine the value of the real bank notes. This would destabilise the entire economy: no one would know which notes were real or which ones were fake. Hitler intended to use the chaos caused by such a scheme as the perfect cover for his invasion of Britain.

Although this plan never came to fruition, the Germans continued to perfect the forging process as part of what was called Operation Bernhard. In December 1942 the forging factory was set up at the Sachenhausen concentration camp just outside Berlin. The Germans brought in experts, often in the form of slave labour, from across Europe. Among those working on the project were a number of people who had previously been convicted of forging bank notes. The German government provided them with all the resources necessary to create forgeries on an industrial scale, including specially produced paper with the watermark in it.

The early attempts were somewhat hit and miss, but the results quickly became nearly indistinguishable from the originals. An expert from the Bank of England would later find a couple of imperfections, but noted that ‘even the graphic expert will not be struck by this difference without comparing with a genuine note, and even then he will scarcely notice it.’ (MEPO 3/2400)

The Germans produced these near perfect forgeries on an industrial scale. Helpfully, as the British investigator later remarked, ‘with characteristic German thoroughness, every sheet of watermarked paper and every note printed had to be accounted for’. These figures indicated that over the course of two and a half years the Germans produced 8,965,085 notes worth £134,610,945, somewhere in the region of £5 billion at current value.

Printing factory (catalogue reference: MEPO 3/2400)

This money was used by the German government to pay for the import of wartime supplies from neutral countries, especially Sweden and Switzerland. This became of vital importance later in the war as inflation rendered the Reichsmark, Germany’s own currency, almost worthless. Forged bank notes were also imported into neutral Spain and Portugal where there was a large black market trade in foreign currency. Ironically some of the first forged notes identified in Britain came from arrested German spies, whose currency had been bought on the black market in Lisbon. As MI5 noted:

‘there is thus the diverting picture of one department of the German Secret Service selling forged notes in Lisbon, and another department of the German Secret Service buying them in the belief they were genuine in order to give them to agents being sent to this country.’ (KV 4/465)

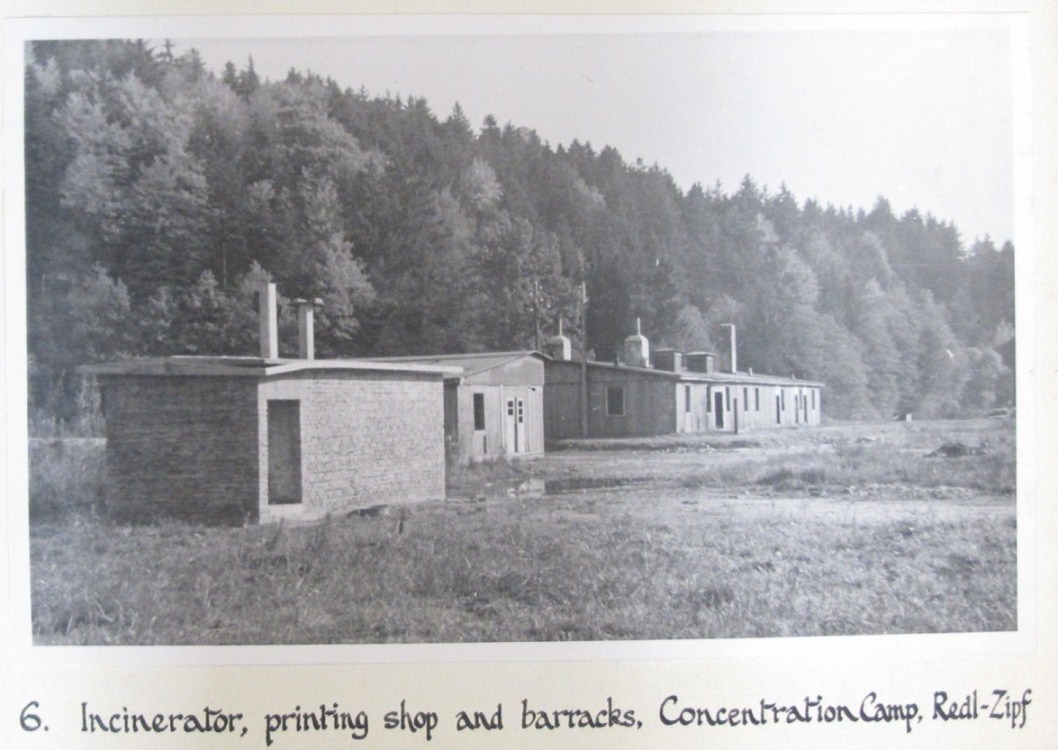

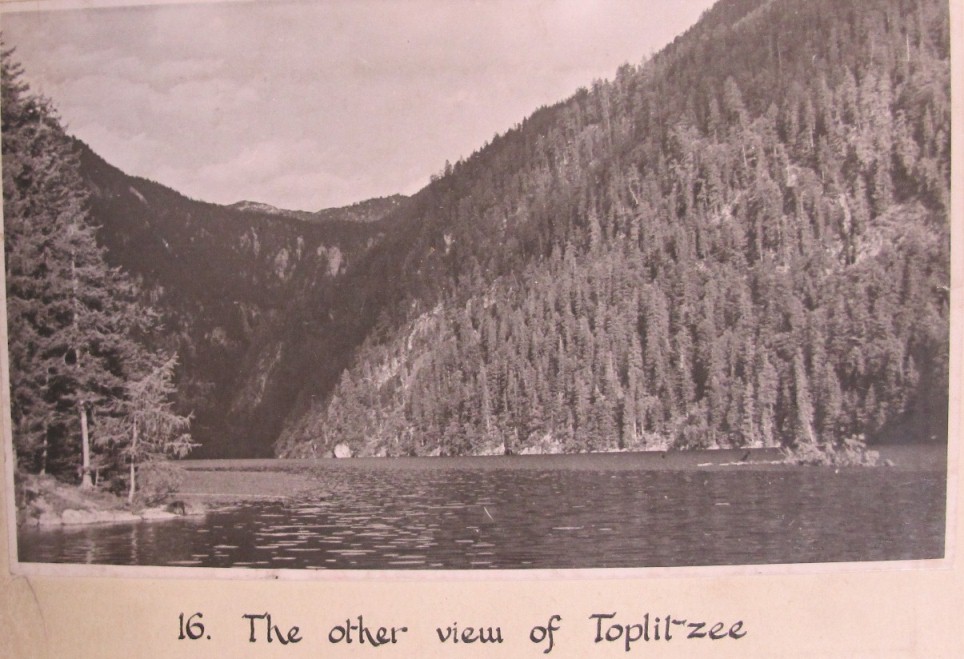

In 1945, as the Allies closed in on Germany, the forgery factory was relocated to a secret weapons testing facility at Redl-Zipf, high in the Austrian Alps. The factory was set up, but no further notes were printed before the area was captured by American forces. The Germans were desperate to cover up their crimes, and so most of the forged currency was burnt. What remained, together with all the special forging machinery, was taken to a remote lake, Toplitzsee, and dumped. It had been intended to execute all of the slave labourers who had been employed in producing the currency in order to stop them from revealing their secrets. Fortunately in the chaos of the American advance, this was never carried out.

Lake Toplitzee (catalogue reference: MEPO 3/2400)

The revelation that the Germans had been forging British bank notes still sent shockwaves through the British establishment in late 1944. The number of bank notes in circulation was carefully controlled by the Bank of England to ensure they maintained their value. The release of vast numbers of high quality forgeries still had the potential to destroy confidence in the British economy and undermine trade with the rest of the world. The Foreign Office, MI5 and the Bank of England carefully monitored the situation and as soon as the factory was liberated a team of investigators from Scotland Yard was sent over to find out what had taken place and recover the forged money before it entered the wider economy. (FO 1046/268)

Chief Inspector W H Rudkin and his team spent a number of months in Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia uncovering all the details of the Nazi programme. They estimated that of the £134,610,945 produced 671,622 notes with a face value of £10,368,445 went into circulation, £1.5 million in Near East, £3 million in France and Low Countries and most of the rest in Iberia. This left £122 million: an estimated half was burnt at Redl-Zipf, £30 million was recovered and destroyed by the Bank of England and roughly £10 million was dumped into the River Enns. This left about £20 million unaccounted for. Rudkin was confident that the remaining money and all of the key Nazi equipment was at the bottom of the Toplitzsee. Attempts to recover the money were hampered by the lake’s extreme depth, and it was decided that it was not worth bringing in specialist equipment from the United States. (MEPO 3/2400)

Although the ultimate German aim of dropping huge numbers of bank notes on the UK was never achieved, and the majority of the forged currency was destroyed, the programme still achieved major results. As MI5 noted in 1945:

‘the German object of destroying confidence aboard in Bank of England notes has been achieved. At present no one will accept a Bank of England note in any neutral country of Europe except at a very large discount.’

The only remedy they suggested was the withdrawal of the old notes and the replacement with new currency. Over time this was exactly what took place. (KV 4/465)

15 years later a German magazine paid a team of divers to explore the Nazi treasure trove at the bottom of the Toplitzsee. This confirmed that vast quantities of forged British bank notes were still in cases at the bottom. The British government was sparked into action and requested that the Austrian authorities recover the notes and the equipment. This was a major undertaking, but eventually almost all of the money which was previously unaccounted for was recovered, along with all the equipment needed to forge bank notes on an industrial scale.

The Austrian authorities together with the Bank of England carefully destroyed this stash, finally bringing the story to a close.

There was also a similar plan by the UK to drop Germen Reichmarks by plane but was not proceeded with because of the possible effects of Germany doing the same. The article is actually not the end of the story (as shown in Treasury files at TNA) the Bank of England and, of course, the Treasury were concerned over the possible circulation of the Nazi Sterling notes that Sterling currency notes were re-issued after the Second World War.

There is an Academy award-winning film based on this: “The Counterfeiters”, an excellent movie – highly recommended.

David, many thanks for your comment. The Treasury angle was one I did not have space to explore in the blog. In fact the Bank of England had been concerned about forgery even before the outbreak of the Second World War, and issued new £1 and 10 shilling bank notes in spring 1940. (T 160/1344/4) Later in the war the Bank began to withdraw notes with a value of £10 and over and these ceased to be legal tender on 1st May 1945. This had more to do with difficulties in policing Exchange Controls than it did with forgery. (T 160/1379/5) When towards the end of 1945 the extent of the forgeries did become apparent a new £5 note containing a metallic strip was rushed into circulation. (T 160/1344/4) These steps meant that by the late 1940s the threat posed by the forgeries had largely gone, but the British government was still keen to bring the matter to a close by removing the notes from Toplitzsee.

Moira, thank you for your comment. I am afraid to say that I have not seen the film, but the story is an extraordinary one.

The forgeries had deliberate mistakes in them that could be spotted if you knew what to look for. I once worked at the BOE and was shown what to look for. Interestingly every white note issued had its own entry in a register giving the date issued and when paid so it was immediately apparent if a note came in that had already been paid. During he Solidarity era in Poland I had the inenviable task of writing to starving Poles that the notes they had sent in which had been passed down by relatives and for which they hoped to get money as they thought they were genuine were these forgeries and were being retained and destroyed.