‘For the future War Savings should be your home guard’ poster. Catalogue reference NSC 5/1037

In June 1940, following a scrambled evacuation of troops at Dunkirk, the Second World War was brought home to Britain. As Hitler’s Luftwaffe initiated its bombing campaign on the RAF in the Battle of Britain, destroying some of our major cities in the Blitz, the threat of invasion grew daily. A secondary defence force of men was set up at home called ‘The Local Defence Volunteers’… later to become known as the Home Guard.

Most men who could fight were already in the forces; those who were left were either too young, too old, or in reserved occupations such as farming, coal mining or ship building (jobs vital to the war effort). After losing 250,000 tons of supplies at Dunkirk, the Home Guard were expected to fight an invasion of German troops with nothing more than a collection of old shotguns and pieces of gas pipe with bayonets welded on the end. It was a desperate time.

However, over a period of a few months, the volunteers evolved into a well-equipped and well-trained army of 1.7 million men. They were armed and uniformed, taking on board instruction from the ‘Home Guard Manual 1941’, from which they learned how to construct booby traps, destroy tanks, ambush the enemy, survive in the open, use basic camouflage, read maps and send signals.

Meanwhile, civilians were urged to ‘keep calm and carry on’, playing their part in the war effort and taking responsibility for their own survival. ‘The British Home Front Pocket Book 1940’ captures the reality of civilian life during the Battle of Britain. It includes many pamphlets and leaflets issued with information and advice – as Britain braced herself for a protracted conflict to fight alone, literally on the front line – on a diverse range of subjects, from how to put on a gas mask to how to build a bomb shelter, and what to do in the event of an air raid.

Meanwhile, civilians were urged to ‘keep calm and carry on’, playing their part in the war effort and taking responsibility for their own survival. ‘The British Home Front Pocket Book 1940’ captures the reality of civilian life during the Battle of Britain. It includes many pamphlets and leaflets issued with information and advice – as Britain braced herself for a protracted conflict to fight alone, literally on the front line – on a diverse range of subjects, from how to put on a gas mask to how to build a bomb shelter, and what to do in the event of an air raid.

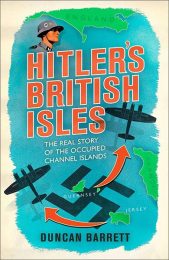

While the Blitz was happening in England, for the people of Guernsey, Jersey and Sark, it was too late: the Germans were already there. For five years, the Islanders were under occupation, watching in horror as their towns and villages were suddenly draped in Swastika flags, their cinemas began showing Nazi propaganda films and Wehrmacht soldiers goose-stepped down their high streets. In ‘Hitler’s British Isles’ there are true-life recollections from the Islanders themselves, with fascinating accounts of life under German rule and some funny tales of individuals trying to get by in almost impossible circumstances. It is a book based on interviews with over a hundred islanders who lived through the occupation, while the rest of Britain escaped that reality.

‘Defending Island Britain in WWII’ describes the real threat of coastal invasion in the United Kingdom along its vulnerable coastlines and inland areas, the preparations made against invasion, and plans for domestic defence. It identifies plans to deny the enemy of resources within specific areas, and describes where coastal defences were also erected and anti-aircraft measures enabled. Today, little remains of Britain’s anti-invasion preparations; only reinforced concrete structures such as pillboxes and anti-tank cubes remain, which can still be found scattered around the country after more than 70 years.

‘Defending Island Britain in WWII’ describes the real threat of coastal invasion in the United Kingdom along its vulnerable coastlines and inland areas, the preparations made against invasion, and plans for domestic defence. It identifies plans to deny the enemy of resources within specific areas, and describes where coastal defences were also erected and anti-aircraft measures enabled. Today, little remains of Britain’s anti-invasion preparations; only reinforced concrete structures such as pillboxes and anti-tank cubes remain, which can still be found scattered around the country after more than 70 years.

Aside from deaths in accidents, the Home Guard lost a total of 1,206 members on duty to air and rocket attacks during the war. They continued to guard the coastal areas of the United Kingdom – other important places such as airfields, factories and explosives stores – until late 1944 when they were stood down. They finally disbanded on 31 December 1945, eight months after Germany’s surrender.

I would like to point out that Scotland also suffered in the Blitz, particularly during the three day raid on Clydebank in March 1941 (https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/research/learning/features/the-clydebank-blitz-13-15-march-1941) and it was not just “England”. As far as the Channel islands goes mention should be made of the evacuation of Alderney by the Germans (as it was nearest to the UK) and I would recommend the books by Dr Gilly Carr of the University of Cambridge and others. It is well-known that some sections of the Home Guard were feared by the regular British Army and were certainly not ‘Dad’s Army’ and the Army avoided them. Surely mention should be made of the Air Raid Precaution staff (my grandfather was one) and of course the war ended in Europe on 8 May 1945 not in April 1945 when Hitler died, they were stood down less than 8 months later.

I wish someone would do an in-depth research into the First World War home guards. How and why they were created and as a complete register or list of their titles, organization, archives or records. Such units were created in Canada, the USA, Great Britain and elsewhere. They directly relate to patriotic fervor, nationalism, war time xenophobia, espionage and sabotage anxieties, unemployment, social pressures and local conditions, etc….

My Great Grandfather who was an ex WW1 (and before) was retired out of the army as a Captain having risen through the ranks. I know he served in India but may also have been involved in parts of Africa. He served on the front in WW1 and in Cyprus.

He ended up in Northampton involved in the Home Guard as his former CO was from Northampton (a well known family). He moved there after evacuating his family from Guernsey just prior to the invasion of the island and had taken part in the watch on the beach prior to the evacuation.

I do not know much about his army career but would love to find out.

Hi Jane,

Thanks for your comment.

We can’t answer research requests on the blog, but if you go to our ‘contact us’ page at http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts by email, live chat or phone.

Best of luck with your research.

Kind regards,

Liz.

What records, if any, exist for the Home Guard, ARP and Fire Watch.

I am particularly interested in the Fire Watch, as my father, who had polio as a child, and consequently was unfit for more rigorous service, served in this capacity.

Hi Thomas,

Thanks for your comment.

We can’t answer research requests on the blog, but if you go to our ‘contact us’ page at http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts by email, live chat or phone.

Best of luck with your research.

Kind regards,

Piriya.

My dad was in the Home Guard in north London, and possibly later in Peterborough. Are there any online records of members, their activities, etc? Thanks – Jean

My grandad Edward Brannen was wounded twice from Dunkirk, he served with the Royal Engineers. I would be very interested to find his army papers and did he get any war medals for that battle ? Where do I find his war records ? from Kew Archives ? I thought that WW2 war papers would not be opened until they are 100 years old ? Please let me know if I can request to find my grandad’s war papers from you. Thank you cherrio Margaret

Your opening paragraph implies that the LDV was set up in June 1940 following the Dunkirk evacuation. It was actually begun with Eden’s ‘call to arms’ which was met with immediate response and enthusiasm on the evening of 14th May, almost 2 weeks before the evacuation of Dunkirk began. Two weeks may not seem that long to us, but bear in mind Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg and France were taken in just 4 days from the 10th to 14th May 1940.