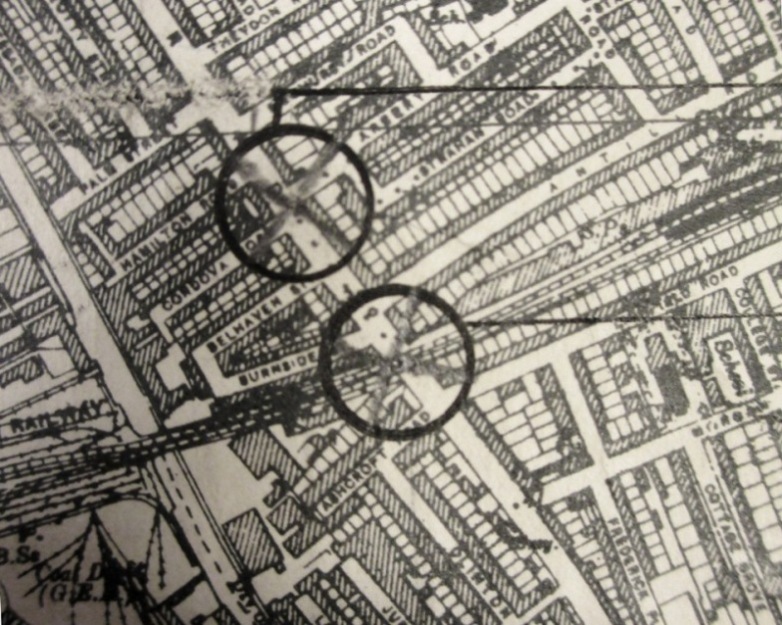

Detail from a Bomb Census map. The Grove Road V1 bomb is the lower of the two shown here. Catalogue reference: HO 193/50, map sheet 56/20 SE (A).

The bombing of British towns and cities during the Second World War was far from uniform. The intensity of the raids, the places targeted and the types of bombs that were used all varied considerably.

One of the most significant changes in the pattern of bombing occurred 70 years ago today, on Tuesday 13 June 1944. In the early hours of the morning, the southeast of England experienced its first V1 raid. This was to be the first of many.

V1 is an abbreviation for the official German name for these devices: Vergeltungswaffe 1 (meaning ‘retaliation weapon 1’). In the British government’s records of the time, the usual term is ‘flying bomb’. Unofficial nicknames included ‘fly’ and ‘doodlebug.

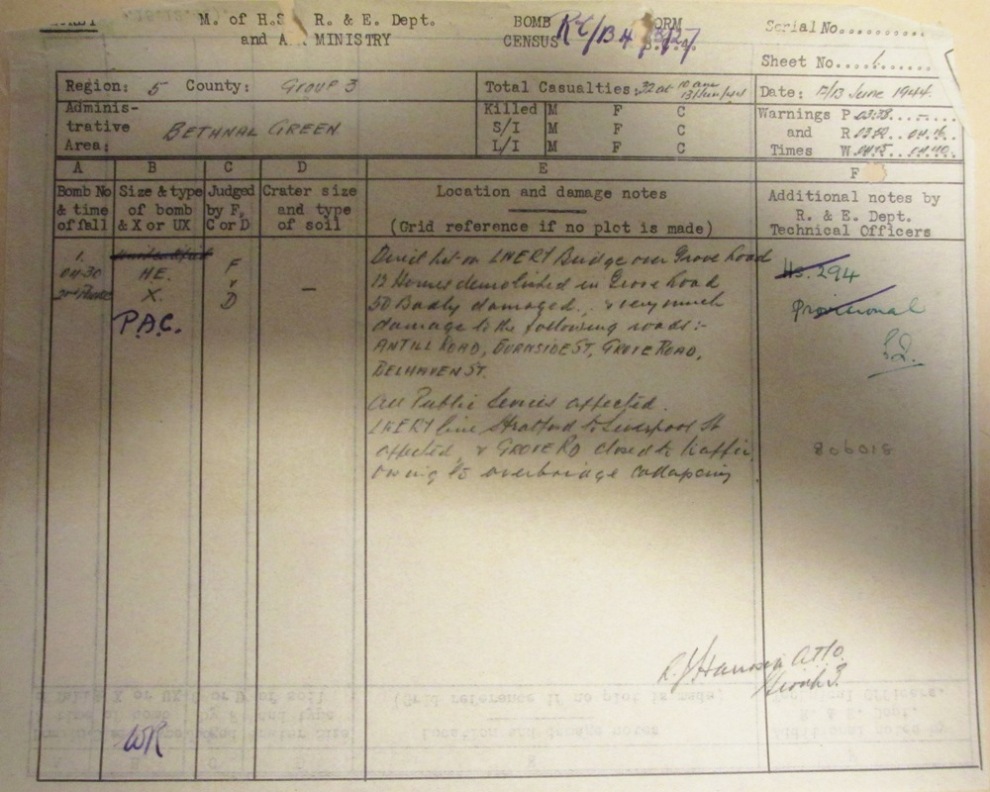

The ‘BC4’ form used by the Ministry of Home Security to record the Grove Road incident. Click on the image to enlarge it. Catalogue reference: HO 198/78, Bethnal Green 12/13 June 1944.

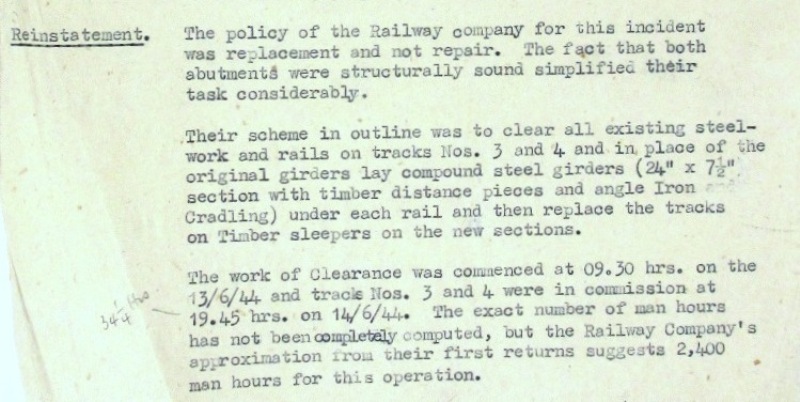

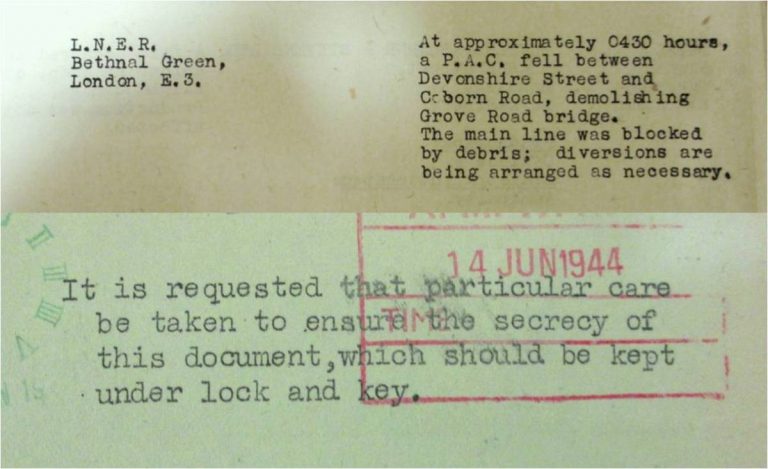

In British records of 13 June, and for the next few days, V1s are referred to as ‘pilotless aircraft’ (or ‘P.A.C.’s). [ref] 1. The minutes of the Cabinet meeting on 19 June 1944 note that flying bomb had replaced pilotless aircraft as the preferred term. CAB 65/42/38, p 122. [/ref] This reflects the fact that – unlike those used in earlier air raids – these bombs were not designed to be dropped from aircraft with human pilots. Instead, they could be launched from mainland Europe, without risking deaths or injuries to members of the German Luftwaffe.

The Ministry of Home Security recorded the fall of four V1s during this first raid. [ref] 2. HO 198/170; see also CAB 65/42/35, p 105. [/ref] Three of these (in Kent and Sussex) had a relatively slight impact. The fourth, however, struck a railway bridge over Grove Road, in Bethnal Green, to the east of central London, causing terrible damage. At least six people were killed and many others injured. [ref] 3. The figure of six deaths is cited in HO 192/492. Different sources for a single bombing incident often cite slightly different casualty rates, sometimes as a result of how soon afterward the figures were compiled. [/ref]

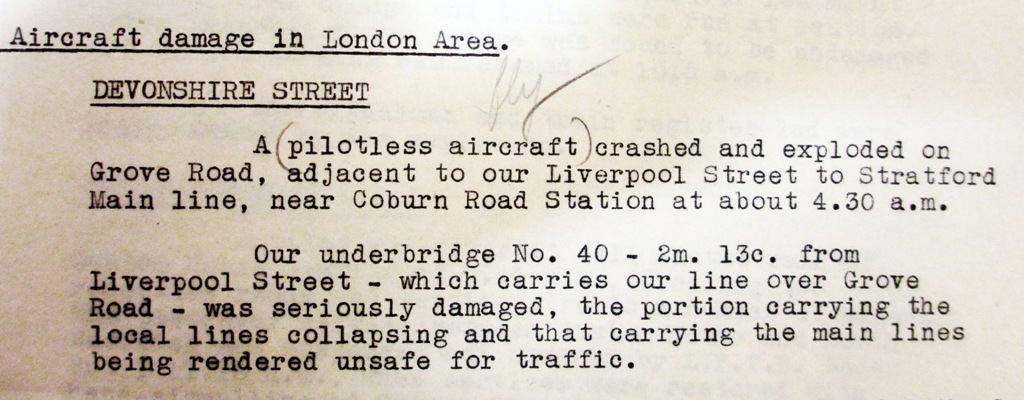

Part of the London and North Eastern Railway’s report on the same incident. Catalogue reference: RAIL 390/1192, report dated 28 June 1944.

The Grove Road bombing was immediately recognised as a new kind of air raid and this fact was highlighted in the reports that were prepared for government ministers and senior officials. [ref] 4. HO 201/16, summary for 12/13 June 1944; HO 202/10, no 208; HO 203/14, no 3490; CAB 66/51/20, ff 106-107. [/ref]

Anxious to learn whatever it could about the effects of the V1s, the Ministry of Home Security investigated this incident far more fully than most bombings. The images below come from a file about the findings of this investigation. [ref] 5. HO 192/492. [/ref]

Air-raid damage files like this one are usually illustrated with diagrams, maps and photographs. This plan shows the damage caused to the bridge itself.

The red circle shows where the flying bomb struck the bridge. Catalogue reference: HO 192/492, plan within preliminary report dated 13 June 1944.

A report describes the London and North Eastern Railway Company’s approach to restoring the damage that had been caused to its bridge. This railway line was an important transport link.

Much of the file consists of typewritten text that outlines the effects of the bomb and the clearance work required in great detail. Catalogue reference: HO 192/492, briefing no 1563, p 2.

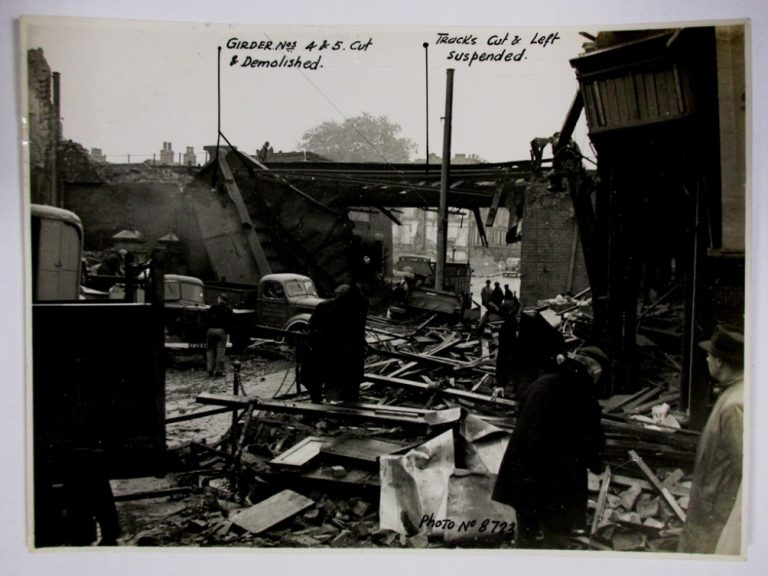

This is one of more than 60 photographs illustrating the effects of the bomb on the bridge and the surrounding buildings.

Points of particular interest to the Ministry of Home Security are labelled on this photograph. Catalogue reference: HO 192/492, photograph numbered 8723 in envelope at the back.

The colouring on this street map records the impact of the blast and debris on nearby buildings. Red indicates the most damaged and green the least. The numbered arrows refer to the angles from which photographs were taken.

This street map was specially copied before being annotated and coloured in by hand. Catalogue reference: HO 192/492, map in envelope at the back.

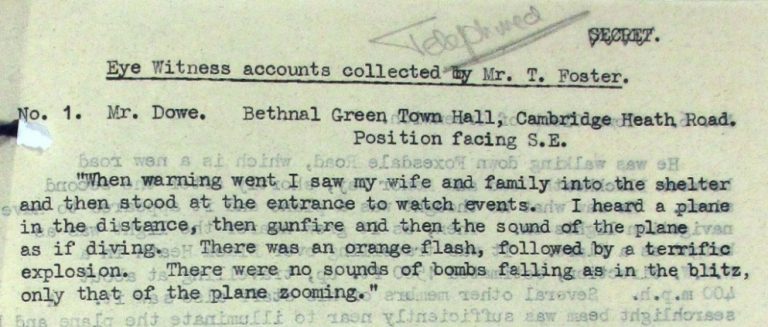

The file also includes some eyewitness accounts. This one mentions the difference in sound between the doodlebug and the types of bombs used during the Blitz of 1940-1941.

A brief account of the flying bomb, as seen from Bethnal Green Town Hall. Catalogue reference: HO 192/492, eyewitness accounts collected by T Foster.

The use of V1s – supplemented from September 1944 onwards by V2s (also known as long-range rockets) – continued until March 1945, but they did not ultimately have the effect that the Germans had hoped. Even before the first deployment of the V weapons, Germany had already begun to lose the war. [ref] 6. The Allied invasion of German-occupied France had begun on D-Day, one week before the Grove Road bombing. [/ref]

Air raids during the Second World War are not always an easy or straightforward topic to research. Please see an earlier post on our blog for some guidance on where to start.

Above: Part of a ‘key points’ report, noting disruptions to essential supplies and services, such as transport links. Catalogue reference: HO 201/22, no 168, p 4. Below: Government records of bombing were kept secret at the time. They were declassified in 1972. Catalogue reference: HO 202/10, no 208, p 1.

I would disagree with the assessment that the V weapons did not have an effect, e.g . the V 1 that fell on Lewisham with people (including my mother and grandmother) fleeing out of the tram they were travelling in. Had the British guns not been moved south out of London to the Kent coast where they had more chance of destroying them then events might have been much different and it was a huge risk at the time. It was Air Intelligence who first noticed the V 1s in France and we wouldn’t have known of the existence of the V 1s and V 2s and the fight they had to get Operation Crossbow to try and shoot them down. The capture of the German spies in the UK and the turning of them to send back false reports also helped.

The V 2s were a big political problem as a number were based in the area around The Hague (the Dutch Government was on our side) and on one occasion a bombing raid went seriously wrong and a large of innocent civilians were killed and Churchill apologised to the Dutch people in Parliament.

Thank you for your comment, David.

I’m afraid that you must have misunderstood what I meant. Of course the V weapons had ‘an effect’. As the records about the Grove Road bomb show, they could and did have a very significant impact on people, buildings and infrastructure.

What deployment of V weapons did not manage to do – despite their devastating power – was to shift the balance of the war back into Germany’s favour.

[…] Doodlebug […]

I remember my mother and her family telling me how terrified they were of these things and the subsequent V2s. Like the eye witness account above they could tell when a V1 was coming down by the engine cutting out and the sound of the dive. They also claimed that a skilled RAF pilot could bring them down by flying alongside and ‘flipping’ them into a dive with their wing tip. Is there any evidence to support this?

In fact, the tipping over happened by disrupting the air flow over the V1 wing rather than physically tipping the aircraft over. The disruption was sufficient to override its gyro and send the flying bomb spiraling out-of-control to the ground.

John,

Captain Eric “Winkle” Brown discussed this in the recent BBC programme Britain’s Greatest Pilot. Tipping the V1s became the standard method of attack as the risk to pilots from debris was too high in a gun attack (as the V1 exploded). He had a personal interest in stopping the V1s – his house had been destroyed by one, fortunately without major injury to his family.

As I recall, it’s also mentioned in Most Secret War by R V Jones (Head of Scientific Intelligence during the war).

I know that Raymond Baxter (of “Tomorrow’s World”) said that he tipped a V1 just as it rose by his aircraft. There is indeed information on the V- weapons in R V Jones’ book, which he wrote reluctantly and that Lord Cherwell (Churchill’s Scientific Adviser) said that Germany could not have created such weapons as Britain hadn’t and then one landed near the PM’s Office and he changed his mind. R V Jones got a special pass soon after D-Day to go and look for the V-weapons , I think it is in DEFE 40/1.

I was told by my cousin Gwen Croxson that my aunt died while she was out

hanging her laundry by a V2 rocket. She may have lived in the Windsor area because that’s where my grandpa was from. I was wondering if there is a newspaper article that reports this happening. My grandpa’s name was Charles W. Hawkins but emigrated to the US after WW1. If someone could tell me something I would appreciate your help.

according to a pamphlet distributed to school children in 1946, which listed major WW2 events, the children were encouraged to write their own family experiences on the back of the page. As well as listing the dates of our father’s departure and return from the Far East, and our uncle’s D-day +4 landing in France, my brother wrote that on “29th June 1944 we were buzz bombed” the V1 fell into our back garden in Purley, Surrey.