Seventy-five years ago today on 2 July 1940, the SS Arandora Star, a British passenger ship of the Blue Star Line, was torpedoed and sunk in the Atlantic en route to St John’s, Newfoundland. On board were 712 Italians, 438 Germans (including Nazi sympathisers and Jewish refugees), and 374 British seaman and soldiers. Over half lost their lives. How did this tragedy happen and why were these foreign nationals classed as ‘enemy aliens’ being transported to Canada? To answer this, we need to understand more about the British policy of internment during the Second World War.

Upon the declaration of war on 3 September 1939, some 70,000 UK resident Germans and Austrians became classed as enemy aliens. By 28 September, the Aliens Department of the Home Office had set up internment tribunals throughout the country headed by government officials and local representatives, to examine every UK registered enemy alien over the age of 16 (since 1914 all aliens over the age of 16 had needed to register their details at local police offices, a requirement of the 1914 Aliens Registration Act (4 & 5 Geo. V c.12). The object was to divide the aliens into three categories: Category A, to be interned; Category B, to be exempt from internment but subject to the restrictions decreed by the Special Order; and Category C, to be exempt from both internment and restrictions.

Some 120 tribunals were established, assigned to different regions of the UK. Many were established within London where large numbers of Germans and Austrians resided. There were 11 set up in North West London alone.

By February 1940 nearly all the tribunals had completed their work assessing some 73,000 cases. The vast majority (some 66,000) of enemy aliens being classed as Category C. Most, but by no means all, of the 55,000 Jewish refugees who had come to the UK to escape Nazi persecution in the early and mid 1930s found themselves in Category C. Some 6,700 were classified as Category B and 569 as A. Those classified in Category A were interned in camps being set up across the UK, the largest settlement of which were on the Isle of Man though others were set up in and around Glasgow, Liverpool, Manchester, Bury, Huyton, Sutton Coldfield, London, Kempton Park, Lingfield, Seaton and Paignton.

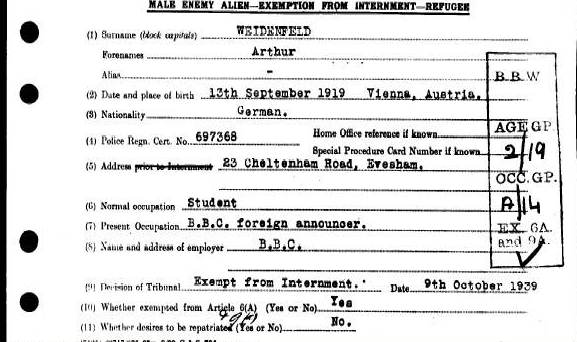

HO 396/98/66: Internmental Tribunal card for future publisher Arthur Wiedenfeld who was exempt from internment because he was a Jewish refugee and was doing useful work as a BBC announcer (foreign programmes)

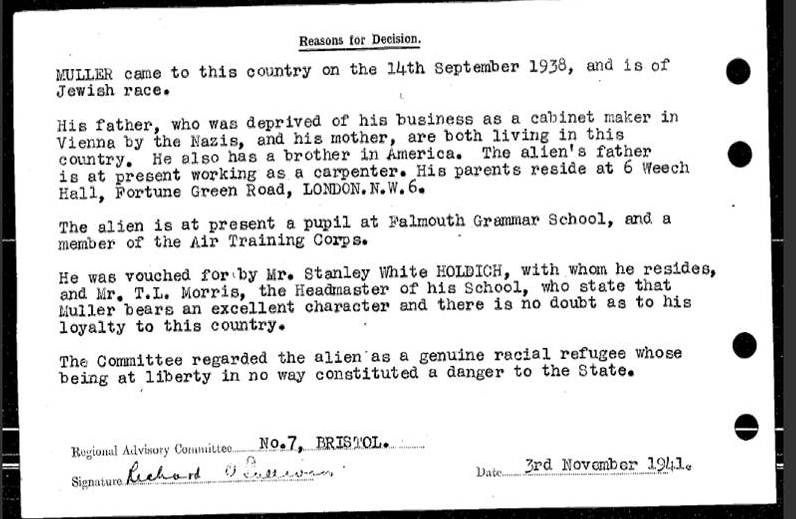

HO 396/63/219: The reverse of the cards can provide detailed reasons why a decision was made not to intern

However, by May 1940, with the risk of German invasion high, regardless of their Category classification, a further 8,000 Germans and Austrians resident in the Southern strip of England, found themselves interned. Resident Italians were also considered for internment following Italy’s declaration of war on Britain on 10 June 1940. Some 4,000 resident Italians who were known to be members of the Italian Fascist Party and others aged between 16 and 70 who had lived in the UK for fewer than 20 years were ordered to be interned.

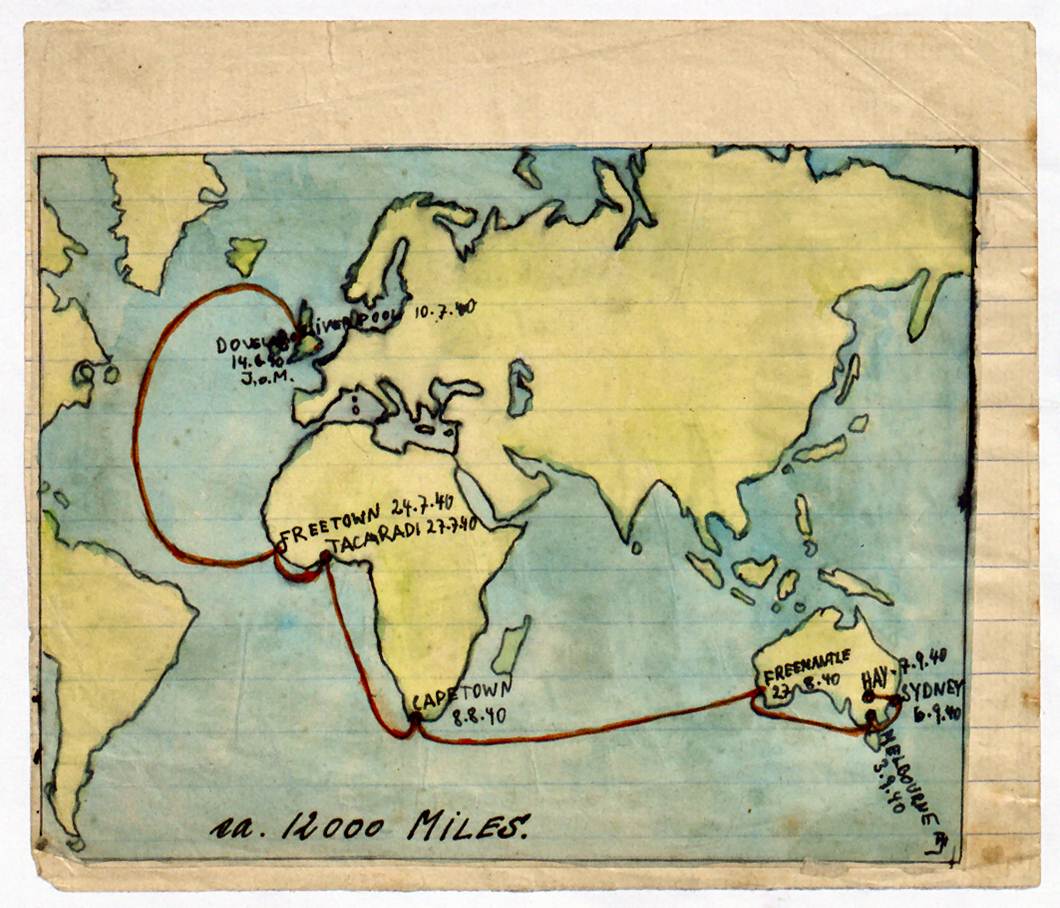

The increase in numbers of those interned led to a serious space problem within the UK and following offers from the Canadian and Australian governments, more than 7,500 internees were shipped overseas on 24 June and 1, 2, 4 and 10 July 1940 on the vessels, the Ettrick, the Sobieski, the Duchess of York, the Dunera, and the Arandora Star. Tragically, in the early hours of Tuesday 2 July 1940, 75 miles west of the Irish Atlantic coast, the Arandora Star was torpedoed and sunk en route to Canada by a German submarine U-47 commanded by Gunther Prien (1908-1941), a prolific German U-boat commander. On board were 712 Italians, 438 Germans (including Nazi sympathisers and Jewish refugees), and 374 British seaman and soldiers. Over half lost their lives.

It was this event that swayed public sympathy towards the enemy aliens. The release of 1,687 category ‘C’ and ‘B’ enemy aliens was authorised in August 1940 and by October about 5,000 Germans, Austrians and Italians had been released following the publication of the Under-Secretary of the Home Office, Osbert Peake’s White Paper, Civilian Internees of Enemy Nationality. The Paper identified categories of persons who could be eligible for release. By December 8,000 internees had been released, leaving some 19,000 still interned in camps in Britain, Canada and Australia. Of the released, some 1,273 were men who applied to join the Pioneer Corps. They would be joined by internees in Canada and Australia but here the process of release would take longer. By March 1941, 12,500 internees had been released, rising to over 17,500 in August and by 1942 fewer than 5,000 remained interned, mainly on the Isle of Man.

HO 215/263. An extract from a diary kept by internee who was shipped from the Isle of Man to Camp Hay, Australia and back.

Unlike records for the First World War, The National Archives has a wealth of information relating to internment and internees during the Second World War. These include papers relating to the policy of internment, individual internees, and the camps in which they were interned. The series of records HO 396 consist of index cards for the Internees Tribunals set up in September 1939. The records, are usually grouped by category of exempted from internment or interned, and by nationality. Within categories they are in alphabetical order by surname. The papers provide personal information on the front such as full name, date and place of birth, nationality, address, occupation, name and address of employer and decision of the tribunal. The reason for the decision of the tribunal for each case is usually noted on the reverse of the card.

The cards have all been microfilmed and are freely available as Digital Microfilm on Discovery. For those cases heard at the start of the war where a decision was made not to intern (categories B and C), you can search by name of internee and then download the digital microfilm to find the relevant card. The remainder of the series relate to aliens who were at some stage interned (category A) and these are available as Digital Microfilm but to browse only, though most pieces are arranged alphabetically by name of internee. The reverse of cards for those interned provides information about the time and location of internment. This information is closed for 85 years, though under Freedom of Information Act, 2000, it is possible to request a review of the information. HO 396 also contains information on internees shipped out to Canada and Australia: these give name, date of birth, and the name of the internee ships with dates of embarkation. Individual internees may have cards in several categories; for example one person may have been interned in the UK, was then shipped to Canada or Australia and finally released from internment and returned to this country, all of which may be detailed in several different pieces.

Further records relating to some 86 individual internees can be found in HO 214, searchable by name. These files deal with individuals interned; chiefly enemy or neutral aliens, but including a few British subjects detained under Defence Regulation 18B. The papers in this series date from 1940. Perhaps the most detailed records of internees are in the series HO 405 for those who went on to take out British citizenship at some point after the war and who permanently settled in the UK. This series relates to individual foreign citizens (mostly European) who arrived in the UK between 1934 and 1948 and ultimately applied for naturalisation. All files include application for naturalisation with police reports. Some also include initial application for visa or employment permit, change of name or business name and World War Two internment papers, as many internees remained in the UK after the war and applied for British nationality in the post war years becoming part of the social fabric of post-war Britain. Files were opened when the individual first applied to enter the UK and continue until naturalisation or death. These files, some 65,000, provide a useful insight into pre and post-war European immigration and World War Two internment. These files are closed for 100 years though more are becoming open under Freedom of Information Act 2000, which allows requests for a review of the information to be made through Discovery, at piece level.

Further records of some internees can be found in the series MEPO 35. This series contains the surviving aliens’ registration cards for the London area. These represent some 1,000 cases out of the tens of thousands of aliens resident in London since 1914. Although the cards represent a small sample there appears to be a heavy concentration of cases around the late 1930s, as Germans and east Europeans fled the Nazi persecutions. The information provided on the cards includes full name, date of birth, date of arrival into the UK, employment history, address, marital status, details of any children, and date of naturalisation with Home Office reference if applicable. They also include reference to internee tribunals and internment. The cards usually include at least one photograph and for some cases there are continuation cards. Cards continue until naturalisation, repatriation or death. Where they survive, cards for other Constabularies are kept locally at County Archives.

Details of internees shipped overseas can be found in BT 27 for outward journeys and BT 26 for return journeys. These are passenger lists of people arriving in and departing from the United Kingdom by sea and were compiled by the Board of Trade’s Commercial and Statistical Department. The information given in these lists includes the age, occupation, address in the United Kingdom and the date of entering or departing United Kingdom by sea from or to ports outside Europe and the Mediterranean. Both series are available online through partnership with Ancestry and The National Archives (BT 26) and Find My Past and The National Archives (BT 27). There are further papers relating to those interned overseas including an embarkation list for the Arandora Star (HO 215/438), the Dunera (HO 215/1), the Ettrick (HO 215/267), and the Sobieski (HO 215/266).

The series HO 215 covers the Home Office and its responsibilities for enemy aliens and (under Defence Regulation 18B) British subjects interned. The series includes reports by the International Red Cross or the protecting power on conditions in British internment camps, and in enemy internment or prisoner of war camps.

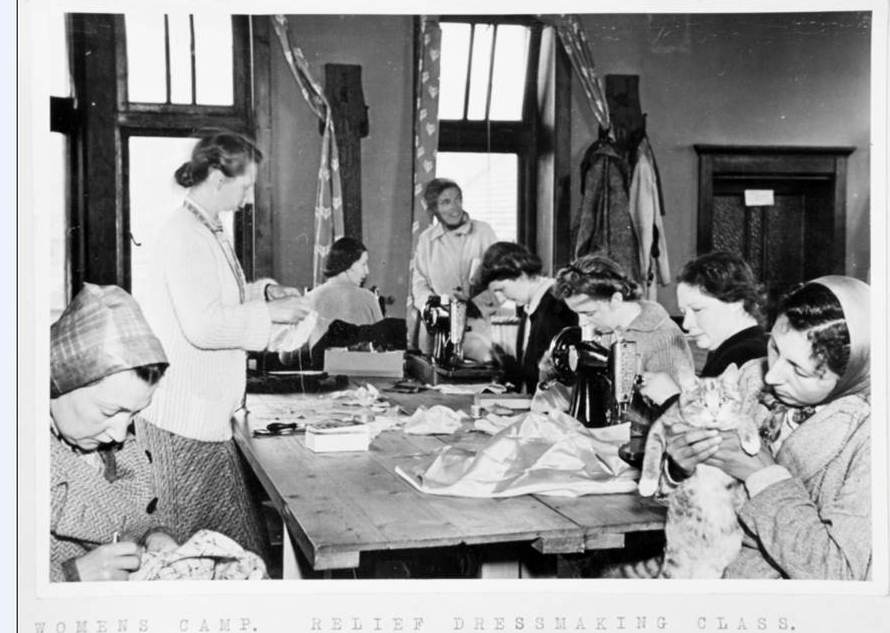

The papers in this series date from 1940 following the institution of mass internment. When camps were established there were often separated into camps for men and camps for women and children. HO 215 include nominal rolls of internees in the Hutchinson, Metropole, Mooragh, Onchan and Port Erin camps on the isle of Man. They also include lists of repatriation to Germany in 1945. HO 213 is a broader series containing policy files relating to the definition of British and foreign nationality, naturalisations, immigration, refugees, internees and prisoners of war, the employment of foreign labour, deportation, the status of citizens of the Irish Republic, and related subjects. There are also papers relating to departmental committees, statistics, conferences, conventions and treaties on these subjects. It contains fascinating files on internment including the document HO 213/1053 which includes photographs of internees and a report of an inspection of camps on the Isle of Man, focusing on Women, children and married couples interned there. The camps would set up its own industries (such as glove making or farm work) and internees were allowed to create their own entertainment, staging plays, concerts and showing films. Many of those interned were artistic, including actors, writers, artists, and musicians.

A glove-making industry. Photograph from HO 213/1053: Women, children and married couples interned on the Isle of Man: report by Inspector Cuthbert, 1940-45, includes a photograph album of a Women’s camp on the Isle of Man

Finally, check Discovery to identify internment records kept at local archives across England and Wales. Plus, there are local records pertaining to the Isle of Man at the Manx Museum.

An interesting file is T 161/1081/4: 1940-1942: COMPENSATION. Prisoners: Home Office: Antonio Mancini and Antonio Pacitto naturalised British subjects drowned in the sinking of the “Arandora Star”; compensation for illegal transportation as it was not just Aliens but those of Alien descent who were moved. The policy of the time was somewhat confused and carried on from the First World War, where those naturalised. Within Government those people like Sigismund David Waley, who were British had Alien descent and even within SOE (Vera Rosenberg/Atkins), despite being Romanian and subject to restrictions until 1943 when they were naturalised even though British Naturalisation during the Second World War was stopped leading to the huge backlog from 1946 onwards.

Thanks you for your comment, David. Indeed, a Discovery search reveals some 26 hits for documents relating to the sinking of the Arandora Star – http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/results/r?_st=adv&_aq=%22arandora%20star%22&_dss=range&_sd=1940&_ed=1940&_ro=any&_hb=tna

Next week an exhibition opens about the loss of the Arandora Star:

Monday, July 6, 2015 till Monday, August 3, 2015

“The Arandora Star Tragedy. 75 years on – London’s Italian Community Remembers” will be held at Holborn Library, Local Studies and Archive Centre, 32-38 Theobalds Road, London WC1X 8PA for 4 weeks.

There are a number of memorials to the Italian dead in the UK and in Italy, see the link below for more details, the page also has a link to a list of the Italians lost:

http://anglo-italianfhs.org.uk/articles/arandora.shtml

A very interesting article. I look forward to researching these links

[…] he was arrested and interned on the Isle of Man in Churchill’s policy of “Collar the Lot!” that saw the mass internment of nearly 30,000 German refugees behind barbed wire. In […]

My grandfather was an internee, and was on the Arandora Star when it was torpedoed. He was Austrian, so your passenger numbers are not 100% accurate, in terms of nationalities at least. My understanding is that the record keeping at the time was a bit of a mess, for various reasons.

I wish there was more to this thread of history about conditions in the camps, the impact on the individual refugees, and where the refugees were resettled after the war. Dr. Russell

Refugees were not necessarily “resettled”. Most resumed the threads of their disrupted lives.I was interned with my mother in May 1940 and spent over a year in Port Erin, on the Isle of Man, where an excellent small school was set up by Minna Specht. We were finally reunited with my father (who was in a men’s camp in Onchan)when a married camp was set up in Port St Mary in the Summer of 1941.

We were released in September 1941and returned to our small flat in London. My father went back to work and I went back to school. I have never forgotten the whole experience and it has coloured my life.

We were released in September and returned to our small flat in London. My father went back to work and I went back to school.I have never forgotten the whole experience and it has coloured my life.

Many thanks for this piece. I’m carrying out research for a friend who’s relative was interned on the Isle of Man, this is very helpful.

Fabulous information. My mother was Classified C Enemy Alien. I have been able to locate a copy of the front of the card, but did not realize there was additional information was on the back, will have to see if I can find the back info. Interestingly the card is dated October 23rd, 1939 and yet my Mother who was living on the coast as Domestic Help was taken to London and Interned in August of 1940. She was interned for a short period of time in a London Prison. My Mom is now over 100 does not remember the name of the prison, but there must be some records of this on this website, but the question is can I find it.

You account of internment is not factually accurate. For example the Canadians did not “offer” to accept aliens, but were asked to accept Aliens by the British government. Initially the Canadians refused to accept the aliens, and only agreed to do so after considerable pressure from the British government, who knowingly misrepresented the status of many enemy aliens as “dangerous” when they were in fact refugees from Nazi oppression. This misrepresentation is very well documented. Can you therefore change the text.

Just where was the expression, ‘Collar the Lot’, written or said? Reference?

My grandfather was drowned in the Arandora incident and was a born British subject (Glasgow) of German Jewish descent. Upon his arrest under Section 18B, he appealed his detention to the Advisory Committee, which recommended internment. Governmental correspondence in his file characterizes his detention, or deportation, or both, as illegal. Should his status as a born British subject have protected him from deportation? One of the officials commented that his dual citizenship (German/British) distinguishes his case from Pacitto and Mancini, who were naturalized, but why should that be? Ultimately his widow (also a British subject) was compensated–after years.

My Grandfather was born in Vienna in 1874 and died in London in 1931. Even though he had been dead for some 8 years before WW2 my Grandmother(who was English) was required to regularly report to the police throughout the war.

I have not been able to find any public record of this although I assume this will be available somewhere.

How long was an enemy alien required to report their movements after the end of WWII ? My wife’s grandfather was still having to report to a police station in order to travel from county Durham to Merseyside as late as 1960. This seems somewhat excessive

My maternal grandfather was a German prisoner of war during world war 2 he told us how much he despised the nazis and that his capture was his freedom . He was offered repatriation to post war West Germany in 1948 but revised mainly because he had settled had a girlfriend who became his wife after her family had him working on their farm he never forgot the kindness of his “ captures” he only returned to Germany on visits to family he joined the British army and did his service my family are proud that grandad when he was 17 years old was captured bad saved from the madness of war when he passed away in 1994 the whole village came out to honour him I miss my grandad even now

My father, Peter Beschizza, was 18 when he boarded the Arandora Star. He wrote his experiences on Izal toilet paper. The 70 year old toilet paper is on show in the exhibition.

My father arrived with his Viennese Jewish family in the UK in 1933. He was sixteen and still at school when he was taken by the police and subsequently interned under the “Collar the Lot” (Churchill’s words) policy. There had previously been a campaign in the Right Wing press against “enemy aliens” and a possible Third Column. On arrival at the first holding camp, my father and his fellow internees were addressed by the Commandant, who said “Good heavens! I never knew so many Jews were Nazis”. Eventually he was shipped to Canada where he was made to cut down trees. On arrival at the camp near Trois Rivières he and his fellow internees were marched up to a compound ringed with barbed wire. Inside were some SS POWs with whom it was proposed that the new arrivals – virtually all Jewish – would be billeted. When the SS men saw the young Jewish men approaching, they went into their huts and came back armed with knives and clubs. Seeing that, my father and his group simply sat down on the ground where they were and refused to move. Thankfully they were then given alternative accommodation. The implementation of the Collar the Lot policy was often characterized by similar insensitivity and ineptitude. A particularly horrific example of this was the transportation of mostly Jewish internees to Australia on HMT Dunera, who, at the hands of the soldiers guarding them, received treatment not far distant from that meted out by the Wehrmacht.

I have included my own story of internment, shipment to Canada on the Sobieski, and eventual release in my memoir: Flight and Refuge. Reminiscences of a Motley Youth. Also in a recent book: Glimpses. ASubdry Life. These 2 accounts will flesh out your account, both are available on Amazon..

@Arlene Hooper My great grandfather was held in Brixton jail, would this be it?

My father, his twin brother and my Grandfather were all interned at the start of WW2 on the IOM.

They had separately escaped Vienna to the UK after the Anschluss.

Following internment the twins joined the British army, my father in the Pioneer corps. was stationed in what he always called Palestine.

During the war both my Jewish Grandparents worked in service for a family in Derbyshire.

After the war as a child I never heard complaints from any of them about this, they were so thankful to have escaped to enjoy the rest of their lives.

My Great uncle who served in the Austrian army in WW1 Russia also survived WW2 as did my Grandmothers other siblings.

My mother visited a fellow Austrian woman who was detained in Holloway Prison (now closed) which was a women’s prison. My mother though classed as an enemy alien was not detained. She had worked in England at the beginning of the ’30s as an au pair to an influential family which must have vouched for her. Detention then and now was hysterical rather than rational.

On 3 July 1940, my father, then Werner Straus, shipped out on the SS Ettrick from Liverpool bound for Canada after a period of captivity in the Onchan Camp on the Isle of Man. It was just one day after the SS Andora Star had been torpedoed and sunk. He had come to Britain to study engineering at Loughborough College and was about to take his final exams when he was forced to give it all up and taken away to an internment camp. He was released after about six months when the British government relented and allowed German-born Jewish refugees like my father–who was 22 when he was interned and 23 when he left–to join the British Army. He was part of the Pioneer Corps and served until 1946. He had married my Scottish Jewish mother in 1941 while serving, and my two older brothers were born while Dad was in the Army. When my mother married my father, she lost her British citizenship. I believe both of them got it back later, but then they moved to America (California) to join my grandparents, who had escaped from Germany in late 1938. Sometime during his service, my father changed his name to Vernon Stroud. If anyone happens to have any more information about him under either of those names I would love to know it. I’m interested in leaving an accurate record of what I know of this chapter of my Dad’s life for future generations. The links you have listed don’t come up with anything about him when I punch in his name.

I used these records to follow up my father, his parents, grandmother and aunt, and his elder brother. I had found a locked safe with their German ‘Nazi’ passports. They all appeared in HO396, HO 214 and HO 405 (especially my father’s elder brother). I have just written up the story in The Locked Safe: a family memoir, published by Authorhouse and available from Amazon online. As a result I met someone (Angela Eden) whose father was also a Jewish refugee from Austria not Germany. She told me that her father’s passport is in these archives. Were these passports of internees (my father, his father and brother) or internees at liberty (my grandmother, great grandmother and great aunt) usually confiscated by the British state? Is that why they were found in 1996 in a locked safe?

Questions Please for Roger Kershaw

On some of the UK ‘Dunera’ Italian internee records (those sent to Australia on the ‘Dunera’) there is a notation: released I.L.B. I am thinking that these men were directed to work in a Labour Battalion, but I cannot find information on the I.L.B. and whether if represents Internee Labour Battalions or Italian Labour Battalions. What were the restrictions? The other abbreviation is RCA. I am hoping that you can assist me.

Joanne Tapiolas

Townsville

Australia

May I suggest you use the Rootschat forum to help you. Many on there have expertise and keen to help.

Hi, there was a camp near Kielder, Northumberland and I’m trying to research its use and potential internment camp used prior/during WW2. Can anyone help me shed some light on this. I’ve got one historical picture, entitled Kielder C.I.C and wondered if this has sent me down the right path to be a concentration and internment camp?

Many thanks in advance

My father was on the Arandora Star. He survived aged 30. He was from Bardi, Italy where over 40 internees came from and died. He was interned on theIsle of Man.