A little while ago I produced a couple of blogs looking at how you can use data from our catalogue to do some basic, but useful digital history. This works very well if the records you are interested in have detailed entries on our catalogue, but not so much if your ‘data’ still takes the form of a bound index or calendar. To get at the amazing information trapped inside what are commonly described as finding aids it is necessary to ‘hack the paper’.

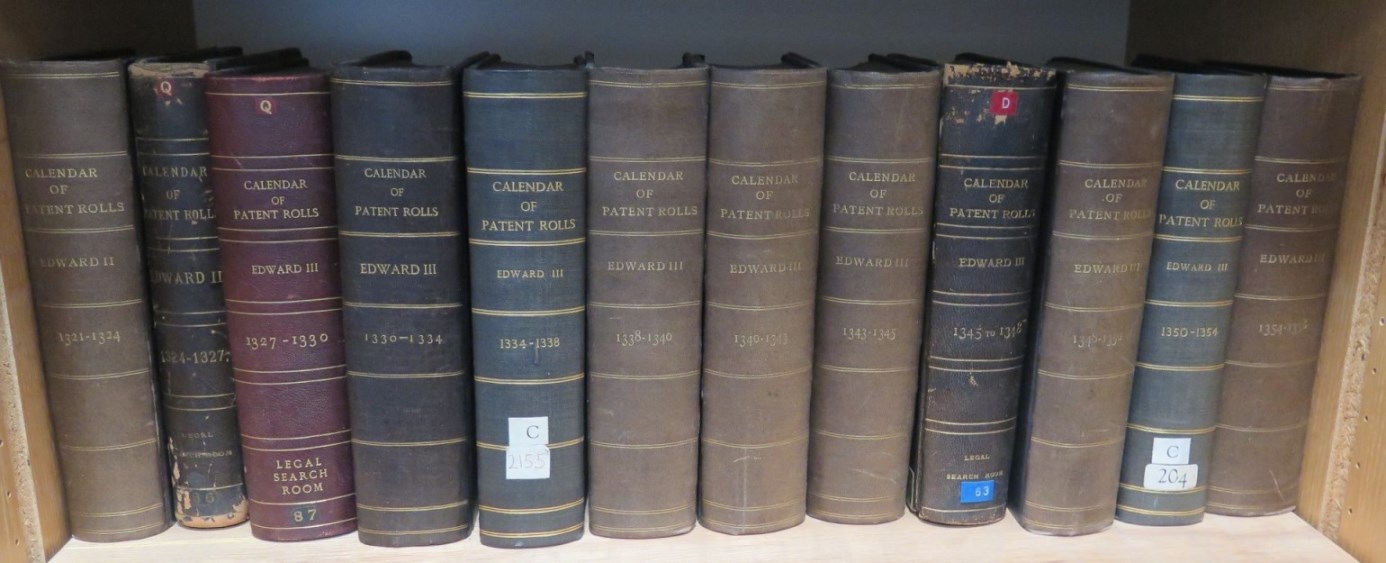

To see how easy this would be, I decided to experiment with one of The National Archives’ most important collections of paper finding aids – the Calendar of the Patent Rolls. These refer to the Patent Rolls held in C 66, an amazing collection of documents that record letters patent, grants and other aspects of Royal administration. In fact, the Calendars produced in the early 20th century by the Public Record Office go far beyond simply being an index: they provide a comprehensive listing of all entries on the rolls with a summary of the contents. This is so complete that virtually all historians now refer simply to the Calendars in place of the original document.

The Calendars contain huge amounts of ‘data’ but this is trapped inside the page, and so I decided to see if I could extract it in a usable form. To start this process I took some decent quality images of one volume of the Calendar of Patent Rolls (Edward III, Volume 14, 1367-70) and ran some optical character recognition (OCR) software over them. I used the ABBYY FineReader software built into the Transkribus platform, but there are numerous other options available. The initial results were mixed – partly a product of the poor quality of the original print – but after some playing around I managed to get something workable out of the software. I exported the transcription and began to experiment with the results.

The problem I faced was that the transcriptions I was exporting as Word or .txt files did not have a uniform layout. On some pages the text was reproduced in the correct format; however, on others it had been read in columns with all the dates and locations at the start of the page and the main body of the text following. This inconsistency made it impossible for me to separate out the data at scale. Fortunately a colleague came to the rescue, providing me with a simple Python script which would take the co-ordinates in an .xml export of the text and use this to set out a basic format.

Page from a calendar showing the different data contained in the document

With this challenge overcome, it became a matter of attempting to separate out all of the data of value on a page so as to be able to use it in a structured fashion. A Calendar page appears relatively simple to read, but actually contains lots of information we would want separated out – notably the reference, the membrane, the year, the date, the location and the entry. To do this I decided to use regular expressions (RegEx). These were relatively new to me, and I got a great introduction to this from Exploring Big Historical Data: The Historian’s Macroscope (you can find the open access draft here).

I found RegEx a little daunting at first, but its power to manipulate text is extraordinary. By using the patterns within the structure of the text (character strings, punctuation, line breaks, and so on) I was able to isolate and ‘mark up’ each of the types of information I wanted to separate out. I did this using a number of special characters. It was a process that took a little time to get right, particularly because the OCR was not perfect, and so the patterns I was using were not absolutely consistent.

Once I was eventually happy with my marked up text, I was ready for the final stage: to put the text into a spreadsheet and separate out the types of data using the special characters. With this complete, I had all the information I wanted in the relevant columns and I could clean it up in the usual way.

The overall process was not a particularly easy one, and I needed a little help from a colleague, but the result was a brand new dataset with well over 3,000 separate entries, and a proven workflow I could use to create more. The raw information contained within this dataset was not new, but the structure allowed me to manipulate and compile it in order to ask some interesting and novel questions. To start with, I decided to plot the frequency of the entries in the calendar chronologically.

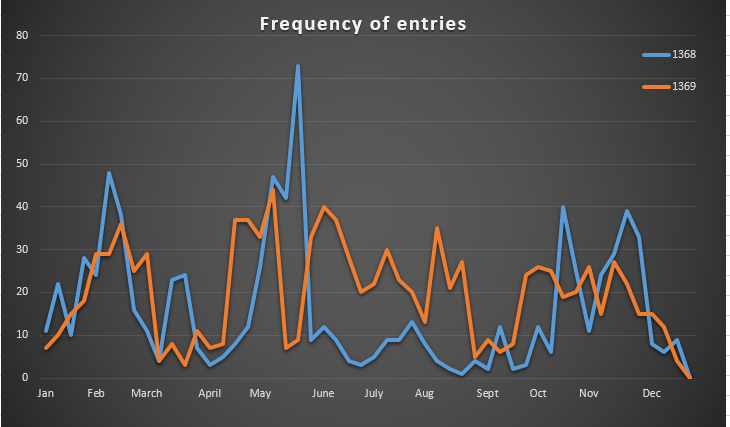

Frequency of entries in the Calendar

The chart above shows the results for the years 1368 and 1369. Although there are clear differences in the graphs, there are certain interesting trends: for example, the peaks in February and early March, and the troughs in early autumn. The above only shows two years, but it would be informative to see if there were broad patterns in the chronological flow of medieval government.

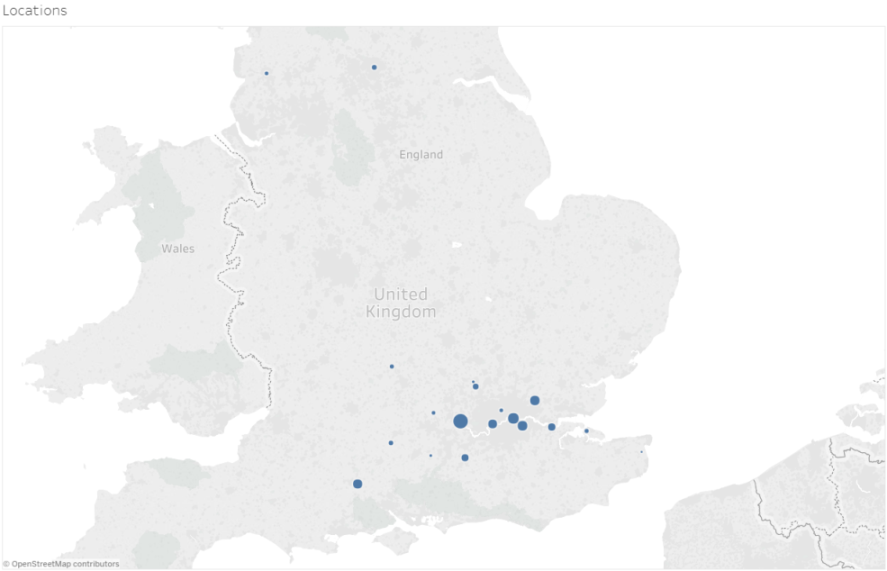

The Calendars also record where the letter patent, grant or the like was issued, adding a potential geographical component to the data. For this volume over 90% of the entries were issued at Westminster, but I decided to plot the remainder to see where the geographical focus of government lay.

Location of issue of entries on the Calendar (Graphic produced in Tableau Public – linked to online version)

The result, perhaps unsurprisingly, shows a strong weighting towards the South East, with Windsor being the second most common location after Westminster. For this blog post I have not had time to connect the geographic and chronological data, but the potential for being able to show changes in the location of governance over time is clear.

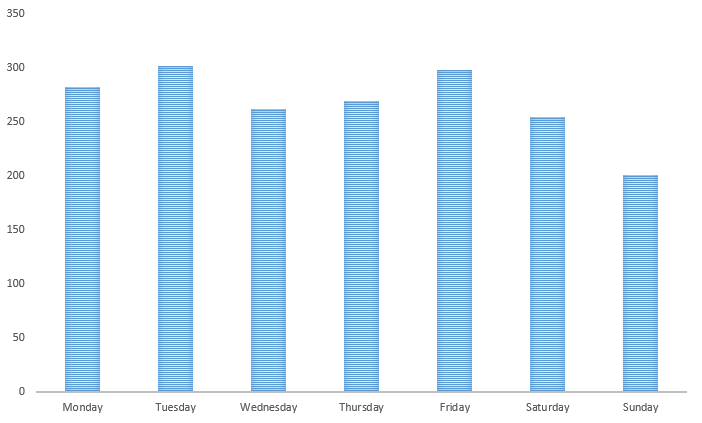

Finally I thought I would end with something fun – finding out what days of the week the documents were issued on. I was not sure if medieval clerks would have worked weekends, but the results seem pretty clear.

Calendar entries by day of the week

With a little more time – and some knowledge of medieval government (unlike your author!) – this data could yield some really interesting new insights, particularly if collected on a larger scale. More generally I think that, although ‘hacking the paper’ is not as simple as downloading a .csv file from our catalogue, this experiment shows that it is possible to extract data from paper collections. When you think about the vast quantity of such material there is to explore, it seems likely that this will be a profitable avenue for researchers in the future.

Very cool. Given that so many of the older calendars have been digitised, there’s potential for, say, student projects to take this kind of thing further and create much larger resources:

https://archive.org/search.php?query=calendar+patent+rolls&page=2

Now, if we could only get these into an online wiki platform that successive projects could work on to clean the data and refine the metadata…

Excellent commentary. Well done to persevere to overcome the problems. Creative problem solving at its best. Looking forward to hear about your next project and/or extension of this one.

February and March peaks may be related to end of calendar year?

The printed calendars do leave out a lot of information (at least the 13th century ones with which I am familiar). They did not bother to include a lot of the routine entries in the dorses of the rolls, particularly the appointments of judges to hear particular cases. So your set of data may be incomplete.

I accumulated similar data for Richard II’s pardons many years ago (before most machine reading) initially recording the data by hand on 3 x 5 cards and then putting it all on what is now an Excel spreadsheet.