On the late afternoon of 7 February 1910, four men in long robes, accompanied by two in western dress, were greeted at Weymouth station by Captain Herbert Richmond and an honour guard. They were taken by Admiral’s Barge to HMS Dreadnought, the flagship of the Home Fleet, and the symbol of British naval might. Here they were shown around the ship by the Commander in Chief of the Home Fleet, Admiral Sir William May.

Virginia Woolf (far left) and the other ‘Abyssinian Princes’ (ADM 1/8192)

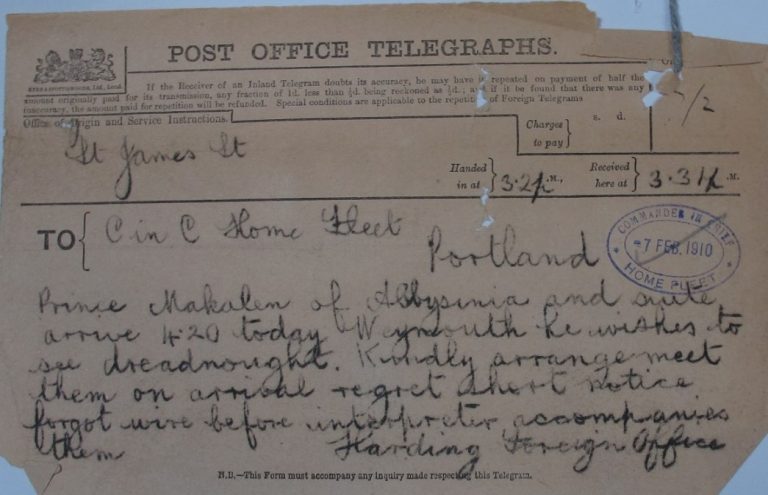

This burst of activity had been initiated by a telegram received by May less than an hour earlier. It reported that Prince Makalen of Abyssinia – with his suite and an interpreter − was arriving at Weymouth by the 16.20 train and requested that they be shown around Dreadnought. It was signed ‘Harding Foreign Office’. In the confusion it was discovered that ‘the Bandmaster didn’t know the anthem of Abyssinia so we played “The Dover Castle March” which had a fairly regal sound’. (FO 800/110/91)

The men spent about 45 minutes going around the ship and left again by the 18.00 train. Soon after they left some began to have doubts about the erstwhile Abyssinians. One of the officers reported that he thought the ‘interpreter had a false beard’. (FO 800/87/71)

The following day ‘a man by the name of Cole’ called at the Foreign Office to say that he had been received aboard Dreadnought ‘in the guise of Abyssinian visitors to this country and he gave the F.O. to understand that the visit was a deliberate hoax’. The Foreign Office were bemused: the initial inclination was ‘to regard the man as mad!’ However the Permenant Under Secretary, Sir Charles Hardinge, ‘thought it right that the Admiralty should be informed’. One can imagine Hardinge’s surprise to be told that an Abyssinian delegation had been received aboard Dreadnought the day before, following his telegram! (ADM 1/8192) After a mad dash down to the General Post Office to get hold of a copy of the telegram, Hardinge confirmed that ‘it was neither signed by him nor despatched under his instructions’.(FO 800/87/73)

Captain Herbert Richmond, a rising star in the navy, wrote to William Tyrrell, Private Secretary to the Foreign Secretary, to give his account. He recalled that ‘The 4 Abyssinians were all introduced as Princes. I hope they weren’t frauds pulling our legs. If they were they did it very well’. (FO 800/110/91)

The Foreign Office and Admiralty officials, still somewhat bemused, would have spluttered on their coffee over the following mornings as the ringleaders told their story in the press. The papers revelled in the hilarious prank played by a group of the Bloomsbury set, led by Horace Cole and including Virginia Stephens (later Virginia Woolf) and her brother Adrian. The accounts detailed how Cole had arranged for the telegram to be sent, purportedly by Hardinge. The group then dressed up with fake beards and costume and even managed to blag a special coach on the train down to Weymouth. The Daily Express reported with barely disguised glee on how ‘the “princes” were shown everything – the wireless, the guns and the torpedoes, and at every fresh sight they murmured in chorus “Bunga bunga”.’ (Daily Express, 14 Feb 1910, in ADM 1/8192)

For the Royal Navy, at the time engaged in a huge arms race with Germany, this was extraordinarily embarrassing. How could the most advanced military organisation in the world allow itself to get duped by a group of men and women in false beards and robes?

HMS Dreadnought (ADM 176/212)

Admiral Sir William May felt humiliated and demanded action ‘to punish the ringleaders’. The Admiralty shared his desire to respond to this affront, and contacted the Foreign Office, stating that in order to prevent further ‘abuse of the telegraph in such a way as to mislead officers in command in the performance of their highly responsible duties, it is considered desirable that the matter should be placed in the hands of the Director of Public Prosecutions’. Hardinge sensibly declined to be involved. He reported that most of the details of what had taken place had been provided by Cole himself and it could not be expected that this would be used in court. (FO 800/87/73)

The Admiralty pressed on and got the Police to open an investigation into who had sent the telegram purporting to be from Sir Charles Hardinge. The police handwriting expert identified the most likely suspect as a Mr Tudor R Castle; however, the Director of Public Prosecutions remained uncertain. As time passed, the Admiralty’s embarrassment faded, and it was concluded that it was better not to press charges. (ADM 1/8192)

Later in the year the Daily Express suggested that the navy got their revenge in a different way. One of the ‘princes’ was apparently told in no uncertain terms to ‘call at the residence of Admiral Sir William May and offer a full apology’. On arriving he was told that ‘his presence was not desired’. Two other ‘princes’ apparently suffered a more violent retribution, being invited to a house in London where they were ‘administered six strokes with a cane’. The Express reported that the individuals ‘submitted to the castigation with lamb-like docility’. (Daily Express 14 April 1910, ADM 1/8192)

Despite this retribution, the story of the hoax continued to resonate, nowhere more so than in the navy itself. The phrase ‘Bunga bunga’ was used by others in the navy to deride their colleagues on Dreadnought, and even ended up in a Portland music hall song.

‘When I went on board a Dreadnought ship,

Though I looked just like a costermonger,

They said I was an Abyssinian prince,

Because I shouted Bunga Bunga.’