On the morning of Monday 6 August 1945 – 70 years ago today – the residents of the Japanese city of Hiroshima awoke to a bright and warm summer’s day. An air raid warning sounded at around 07:00, but no bombs fell and the all-clear was given an hour later. Father John John A Siemes, a philosophy professor, was sitting in his room 2 km away from the city: ‘Suddenly – the time is approximately 8:14 – the whole valley is filled by a garish light which resembles the magnesium light used in photography, and I am conscious of a wave of heat’ (CAB 126/252). Other eye-witnesses ‘saw a blinding white flash in the sky, felt a rush of air and heard a loud rumble of noise, followed by the sound of rending and falling buildings. All also spoke of the settling darkness as they found themselves enveloped by a universal cloud of dust’ (PREM 8/194). An atomic bomb had exploded above their city.

The first wartime use of a nuclear weapon represented the culmination of the Manhattan Project. Emerging from humble beginnings, the project eventually grew to employ 130,000 workers and consume over $2 billion (approximately equivalent to $26.5 billion in 2015). Despite its size, the project remained so secret that even Vice President Harry S Truman was unaware of its existence until he succeeded Franklin D Roosevelt as President in April 1945. Co-operation with Britain’s nuclear weapons development programme, codenamed Tube Alloys, was formalised in the 1943 Quebec Agreement. An arrangement to continue collaberation after the end of the war was made at a meeting between Prime Minister Winston Churchill and President Roosevelt in Hyde Park in September 1944 (PREM 3/139/10).

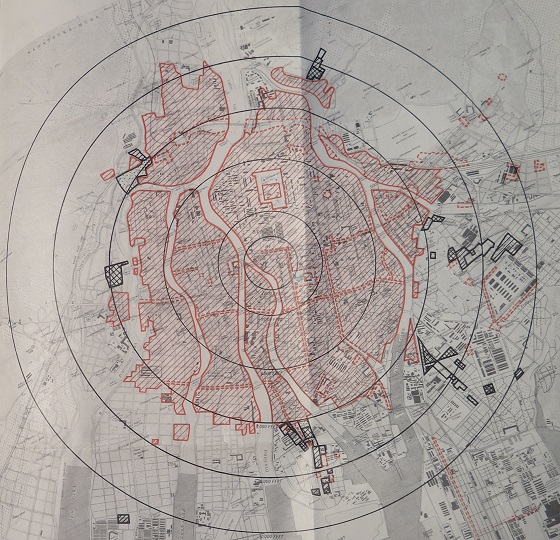

A map of Hiroshima showing the effects of the bomb. The red hatched areas represent fire damage (catalogue reference: PREM 8/194)

Work on selecting targets for the atomic bomb began in spring 1945. Major General Leslie R Groves had been responsible for the overall direction of the Manhattan Project since September 1942. He emphasised that these targets should be chosen so as to adversely affect Japan’s morale and ability to continue the war. As the bomb was expected to do its damage through the initial blast, followed by subsequent fires, target cities needed to contain a large proportion of closely-built frame buildings. They should also have suffered no prior bombing, so that the full impact of the bomb could be demonstrated. Hiroshima was identified as one such target. Its strategic significance came from being home to the headquarters of the Japanese 2nd Army, which commanded the defence of southern Japan. It also acted as a communications centre, a storage point, and an assembly area for troops.

The dawn of the atomic age came on 16 July 1945. An implosion-design plutonium bomb nicknamed ‘The Gadget’ was successfully tested in the New Mexico desert under the operational codename of Trinity. The Hiroshima weapon was available from 31 July. Nicknamed ‘Little Boy’, this bomb was a uranium gun-type device weighing 9,700 lbs. It was dropped from a Boeing B-29 Superfortress bomber – named Enola Gay after pilot Colonel Paul W Tibbets’s mother – and detonated at around 2,000 ft. above ground level. By air bursting the weapon at this height, American planners hoped to maximise the effect of the blast while minimising radioactive fall-out.

J Robert Oppenheimer, the physicist who oversaw the design the bomb at the Los Alamos development facility, estimated that 20,000 people would die in the attack. The report of the British Mission to Japan, ‘The Effects of the Atomic Bomb at Hiroshima and Nagasaki’, put the actual figure at four times that number. In addition, powerful gamma rays proved deadly to nearly everyone exposed to them up to half-a-mile from ground-zero. Out of 23 people that survived the initial blast in one concrete building, only two lived beyond 17 days. These survivors were on the ground level, shielded by the upper floors and by adjacent buildings (PREM 8/194).

A typical Japanese fire engine in 1945. The country had only a limited amount of more modern equipment (catalogue reference: FO 371/59640)

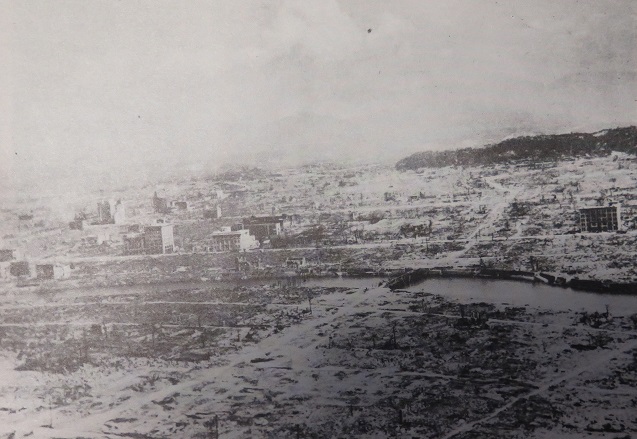

The bomb destroyed over four square miles of the city. In the city centre, ‘everything but the reinforced concrete buildings had virtually disappeared’ (PREM 8/194); ‘a desert of clear-swept, charred remains, with only a few strong building frames left standing was a terrifying sight’ (CAB 126/252). Later estimates put the yield of the explosion as high as 15 kilotons (the equivalent of 15,000 tons of TNT). It took a month for debris clearance and cremation of the dead to begin, and ‘members of the Mission still stumbled upon undiscovered skeletons’. In view of the extent of the destruction, the Mission concluded that ‘no civilian defence services in the world could have met a disaster on this scale’ (PREM 8/194).

A second bomb was used against the city of Nagasaki on 9 August. Kokura – the backup target for the first attack – had been the primary target that day, but weather conditions and lingering smoke from the firebombing of nearby Yahata forced a change of plan. This bomb, ‘Fat Man’, was of the same type as the one tested in New Mexico. It proved even more effective than ‘Little Boy’. On the same day, the Soviet Union entered the conflict on the side of allies. The war finally came to an end the following week. After Cabinet deliberations – and an attempted coup by a faction of the Army that wanted to continue fighting – Emperor Hirohito announced Japan’s surrender on 15 August.

The decision to drop the bomb has provoked much debate. In 1947, Henry L Stimson, US Secretary of War from 1940 to 1945, wrote an article for Harper’s magazine defending the use of the weapon. The American operation to take the small, sparsely populated islands of Okinawa resulted in large-scale loss of life, and plans for Operation Downfall, the invasion of mainland Japan, envisaged a particularly high death toll. Stimson therefore argued that the bomb was necessary in order to shorten the war and save lives. This view was challenged by Gar Alperovitz’s Atomic Diplomacy: Hiroshima and Potsdam (1965), which made the case that the use of atomic weapons was not needed to end the conflict. As The National Archives’ @ukwarcabinet Twitter feed shows, operations against Japan continued apace throughout July. By August, the firebombing and blockade had left Japan on the brink of surrender. For Alperovitz, American policy-makers’ main motivation for using the bomb was a desire to intimidate the Soviet Union as they looked towards the post-war international order. Whatever the rationale behind its use, however, the deployment of a nuclear weapon at Hiroshima continues to cast a long shadow over the world.

I was 11 years old when the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and there was no question that they forced the surrender of Japan. Speculation after the fact is foolish considering the tremendous loss of life during the campaigns against the Japanese in Southeast Asia and in the Pacific. This included the battles of Iwo Jima, Saipan, Tarawa and Okinawa where the Japanese defenders fought virtually to the last man. Why would anything be different on mainland Japan? There is no known evidence that the military commanders in Tokyo were on the verge of surrendering, and in fact when Emperor Hirohito prepared his unconditional surrender speech to broadcast to the nation, a group of officers attempted to stop him, including his assassination if necessary. A war weary world was only too happy to see the use of the atom bombs and to this day I believe they hastened the end of WW II.

German citys were fire bombed to shorten the war against germany, so why not japan.

they were not about to give in so easily. The west had to use this weapon to bring the war to an end. As Winston Churchhill once said: Desperate times call for desparate measures.

My father was a civilian internee at Changi, Singapore 1942-1945. There were rumours that mass graves were prepared for the POW’s but I have seen no conclusive evidence that they existed or would have been used to bury executed prisoners. However, what was far more likely is that the Japanese would have attempted to march the POW’s northwards up the Malayan Peninsula had they had to withdraw from Singapore and make a fighting retreat. Such a withdrawal would have taken place some time after the summer of 1945 given the vastness of the territory occupied in Indonesia, the Phillipines and the British colonies in the area – and the oft-expressed determination of the Japanese local commanders to contest every inch and not to surrender. By that summer of 1945, many prisoners had already died of malnutrition, disease and hard labour under tropical conditions. The existing survivors would have hardly been able to endure a death march. So I am convinced that the dropping of the bombs and the relatively rapid surrender, (opposed In Singapore!), saved the lives of very many POW’s, (including my father), as well as thousands if not tens of thousands of local residents throughout the ‘Co-Prosperity Sphere’ – as well as a great many Japanese!

However, the bombs incinerated a great many Japanese, including conscript soldiers and children, (who had no responsibility for Japanese atrocities, of which there were many between 1931 and 1945). The fact that those children had to die so that I could know and love the father who would otherwise just have been a photograph and at best just a dim five-year-old’s memory poses for me an insoluble ethical dilemma. An obscene irony is that many Japanese soldiers returned home to Hiroshima and Nagasaki never to know or rear THEIR children. I am extremely proud of my many military, naval and airforce ancestors whose names are in the British, French, Spanish and Austrian archives but possibly, as the central character in the old movie ‘Wargames’ opines: War is a game better not played.

Many thanks for your comments. The decision to use the bomb goes beyond the scope of this post, but it remains controversial. J Samuel Walker’s revised Prompt and Utter Destruction: Truman and the Use of Atomic Bombs against Japan (2005) provides a good introduction to the more recent debates.

I recently sent this to The Oldie Magazine for a history column they promote. I thought this might be of interest to readers of this Blog

Meeting my father – a war time journey

In March 1945 when I was 5 years old, I set off from Southampton with my mother on a long journey which eventually led to meeting my father, a former Japanese PoW at La Guardia airport, via an Atlantic crossing, New York and Martha’s Vineyard.

My father was an RAF pilot. Even though he test flew Spitfires in 1938, he was sent to Singapore. Subsequently he became a Japanese POW; my mother was American. We were living in Surrey and she decided that the war in Japan would carry on for a long time, as she did not have second sight. In addition of course there was no certainty that my father would get back. We sailed from Southampton on the SS Argentina, which was fitted out as a US troop ship. There were no railings on the ship, to enable a quick entry into the lifeboats, if the ship was sunk. Consequently I spent 3 weeks in reins. We sailed in a convoy and were in a cabin with 11 others; all ships in the convoy survived. There was a story that there were German POWs in the hold. We eventually sailed into New York harbour, tears streaming down my mother’s face as we passed the Statue of Liberty. After landing in Manhattan, we went to Staten Island to live with my grandmother.

My mother had a close friend with a house on Martha’s Vineyard and we went to stay with her in August 1945. We were on a beach in Edgartown on August 15th and heard the news that Japan had surrendered, with tears streaming down the faces of everyone on the beach. Fire engines rushed around the island, broadcasting the news.

My father spent most of the time as a POW in Palembang in Sumatra. In April 1945, the Japanese moved most of the senior officers to Changi Prison. The probable reason was that the Japanese wanted all officers in one place, so that they could be executed if the Allies invaded Japan.

He eventually got back by ship to Liverpool in early November 1945. The POWs were met by a police band, which only added to the impression of being forgotten three months after VJ Day. While he was on the ship, a tug of war via multiple telegrams developed between my mother in New York and her in-laws in Bournemouth. I still have the telegrams. His parents wanted my mother and me to sail back to England, as they believed he would never be able to get a seat on a plane to New York. Of course he did find a way over, with the help of the RAF; he landed in Montreal and then caught a DC3 flight to Laguardia airport, where I met him in November 1945. More tears.

My father resumed his RAF career in in 1946. My mother and I sailed back on HMS Queen Mary, still fitted out as troop ship.

How much of the events I was part of, do I remember? Much of them, no doubt due to the extraordinary time I was living through as well as the stress my mother was under.

I’ve come to this post at the end of August 2020.

I’ve found it’s the details that make this and similar National Archives post what they are.

This one is no exception. Most people know the general ‘headline’ story. Many are familiar with facts like the British involvement.and the differences between the two devices.

But things such as the military aspects of WHY Hiroshima was chosen down to the images of a target map – so familiar to those who study RAF Bomber Command operations and yet made even more chilling with the fire bomb areas highlighted – and the Japanese fire appliance make this a sobering read any time but even more so close to the commemoration of the end of the Second World War.