They are demonic spirits that perform signs, and they go out to the kings of the whole world, to gather them for the battle on the great day of God Almighty (…). Then they gathered the kings together to the place that in Hebrew is called Armageddon. 1

In English, we call it Megiddo. Megiddo – now in the north of Israel, about 25 miles from Haifa – is a place where some of the greatest battles in history have taken place. The Book of Revelation, the last Book of the New Testament, gives it as the location of the final battle between Good and Evil, and of the end of the world. Around 1457 BC, Pharaoh Thutmose III put the King of Kadesh’s Canaanite troops to rout in what is now known as the first battle properly recorded. A hundred years ago, in September 1918, General Edmund Allenby won arguably the most decisive yet least discussed British victory of the First World War.

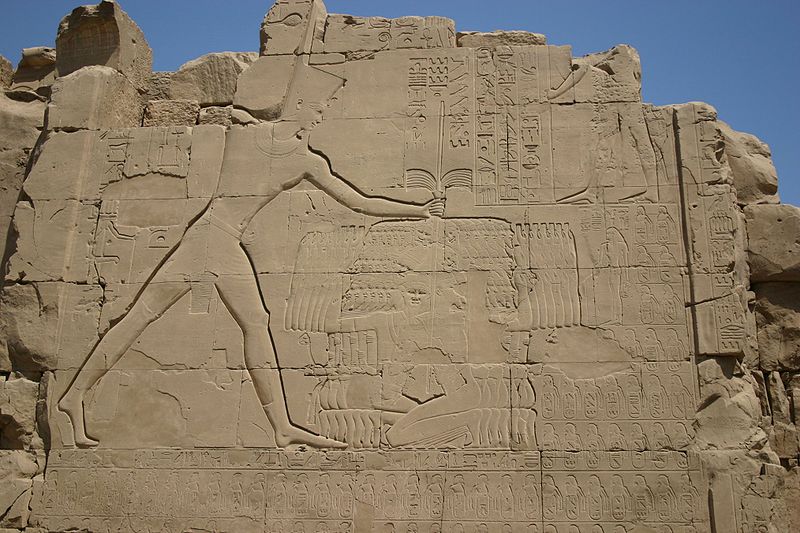

Bas-relief of the temple of Karnak, Luxor, showing Thutmose III after his victory at Megiddo (© Juliette Desplat)

There are actually more similarities than you may think between Thutmose’s and Allenby’s epic victories. Both had long-lasting effects on their military campaigns in the region and in terms of propaganda, and both involved a fair bit of deceit.

The British advance into Palestine had started in 1916 when General Sir Archibald Murray’s Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) defeated the Ottomans at Romani, 23 miles east of the Suez Canal. Two years later, Gaza, Beersheba and Jerusalem had been captured in a steady advance coordinated by Allenby after his appointment in the summer of 1917. With the Ottoman forces now on the back foot, it was time to push on towards Damascus and Aleppo.

The Sykes-Picot agreement of 1916 cast a political shadow over these military operations as the French continued to remind the British that Syria was to fall within their sphere of influence: Emir Feisal and his Arab troops, advised by T E Lawrence, were told not to start advancing on Damascus without Allenby’s consent.

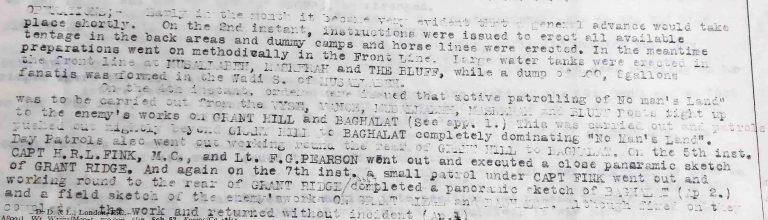

Ahead of his time, Allenby resorted to fake news to convince Liman von Sanders, the German General at the head of the Ottoman Army, that he would attack Lower Jordan. To give the impression that reinforcements were being gathered in the Jordan Valley, troops would, by day, march down from their camps in the hills. They were brought back at night in lorries and sent out again on the following day. Orders for fodder for thousands of horses were planted and ‘dummy camps and horse lines were erected’. Mules were also drawing sleighs across the sandy ground to create dust clouds at watering time.

In the meantime, troops were moved to the coastal area at night, and hid in orange groves around Jaffa. Open fires were forbidden, and kitchens had to use solidified alcohol to prevent smoke. In much the same way as was seen in the summer campaigns of the Western Front in 1918, total surprise was of paramount importance to Allenby’s plan (WO 95/4732).

Extract from the War Diary of the 1st Battalion, British West Indies Regiment, 26 August 1918 (catalogue reference: WO 95/4732)

Despite these preparations, one of the primary concerns at GHQ on the eve of the offensive was whether Ottoman forces had, in fact, withdrawn from their frontline positions. Alhough this would not have been fatal to the impending operations, it certainly would have limited their impact. Much of this fear stemmed from the Turkish capture of a suspected deserter from a British Indian regiment, although Allenby remained convinced of the success of his deceptions. If the secret had been leaked it was not acted upon.

Beginning on 19 September, the Allied infantry – made up primarily of British and Indian units – was to smash a hole through the enemy’s defences on the plain before wheeling right, thereby opening the way for the Desert Mounted Corps.

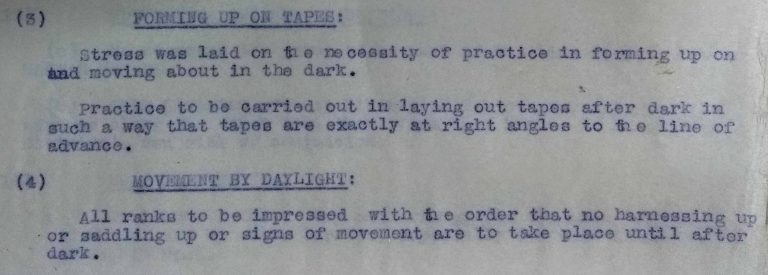

As had been seen in recent British offensives in France, there was to be no preliminary bombardment in this opening phase, sometimes referred to as the Battle of Sharon; just a sustained and intense rolling barrage beginning with the infantry advance at 04:30. This time had been selected to allow for a brief period of moonlight followed by 35 minutes of darkness before the first signs of dawn. During this period the infantry would form up, ready to follow the taped lines that marked the axis of their advance.

Notes from XXI Corps Commander’s Conference, 10 September 1918 (catalogue reference: WO 158/623)

At zero hour, the massed British artillery and two Royal Navy destroyers off the coast began firing over 1,000 rounds a minute into Ottoman lines; while counter-battery fire was so well planned and delivered that it reduced Turkish retaliation to near nothing. Resistance offered to the infantry was also limited.

Similar to experiences at Amiens on the Western Front the month before, nature presented a more trying obstacle. Fog had limited visibility along the Somme; in the desert, dense clouds of dust thrown up by shelling reduced visibility to little over 10 metres at times. Once the infantry advanced beyond the guidance tapes, they were forced to rely on compasses to find their way.

Despite these difficulties, and although some prepared positions offered greater resistance – Et Tire with its trench networks and cactus hedges, for example – many of the first objectives were taken so quickly that the attacking forces had to wait for the rolling barrage to move on to its next target before advancing further. By 10:00, the Desert Mounted Corps moved through the gap created by the infantry and began pushing along the coast and then east, cutting the Ottoman lines of communication and threatening their encirclement.

Over the course of 19 and 20 September, two Ottoman armies – the Seventh and Eighth – had been effectively been routed. The retiring Ottoman forces were subjected to sustained aerial attack by the RAF throughout the battle, but particularly during this retreat: its aircraft caused significant casualties to the fleeing columns and forced many soldiers to abandon their arms and equipment. By 23 September, the Battle Situation report stated: ‘the 7th and 8th Turkish Armies have virtually ceased to exist. Their entire transport is in our hands. By 8p.m. on the 22nd, 25,000 prisoners and 260 guns have been counted.’ (CAB 24/64/58)

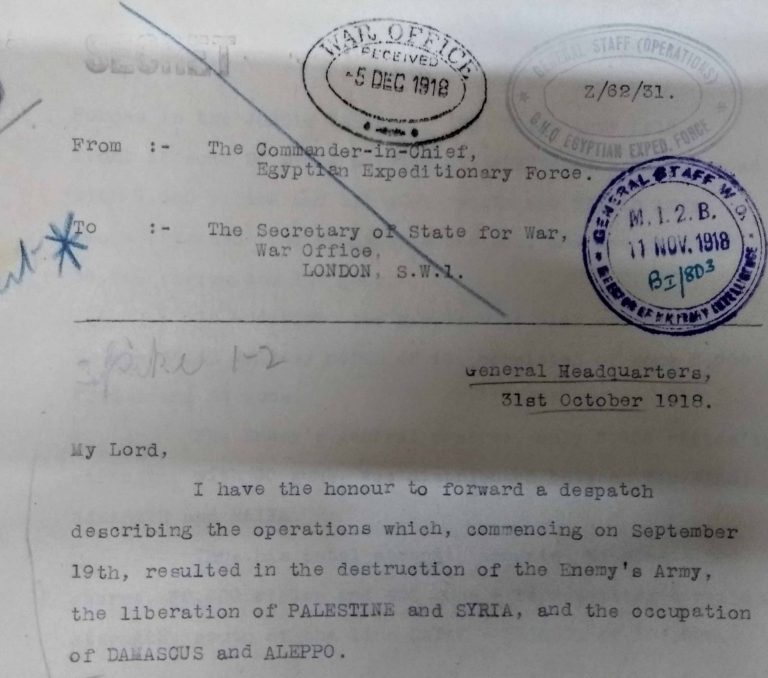

The opening paragraph of Allenby’s despatch forwarded to the War Office at the end of October 1918 (catalogue reference: WO 32/5128)

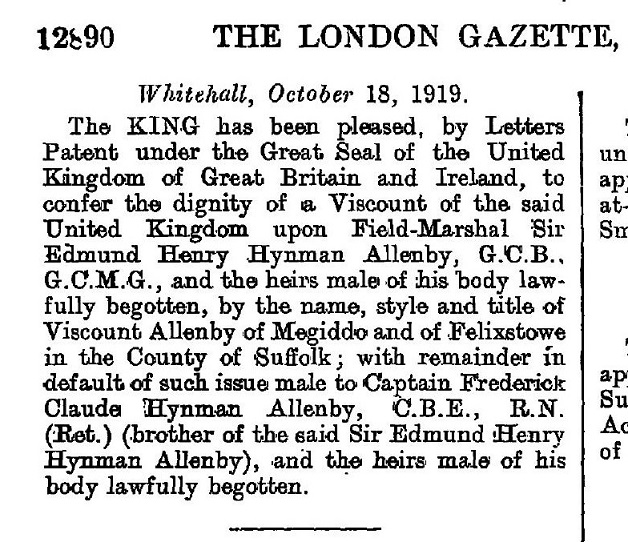

There had not been much more than a skirmish at Tel Megiddo but Allenby could not resist the historical significance of the name. He had seen the effectiveness of religious propaganda when he had entered Jerusalem on foot in December 1917, and so the series of battles actually fought around Galilee became the Battle of Megiddo. Allenby himself, now a Field Marshal, became Viscount Allenby of Megiddo and of Felixstowe.

London Gazette, 18 October 1919

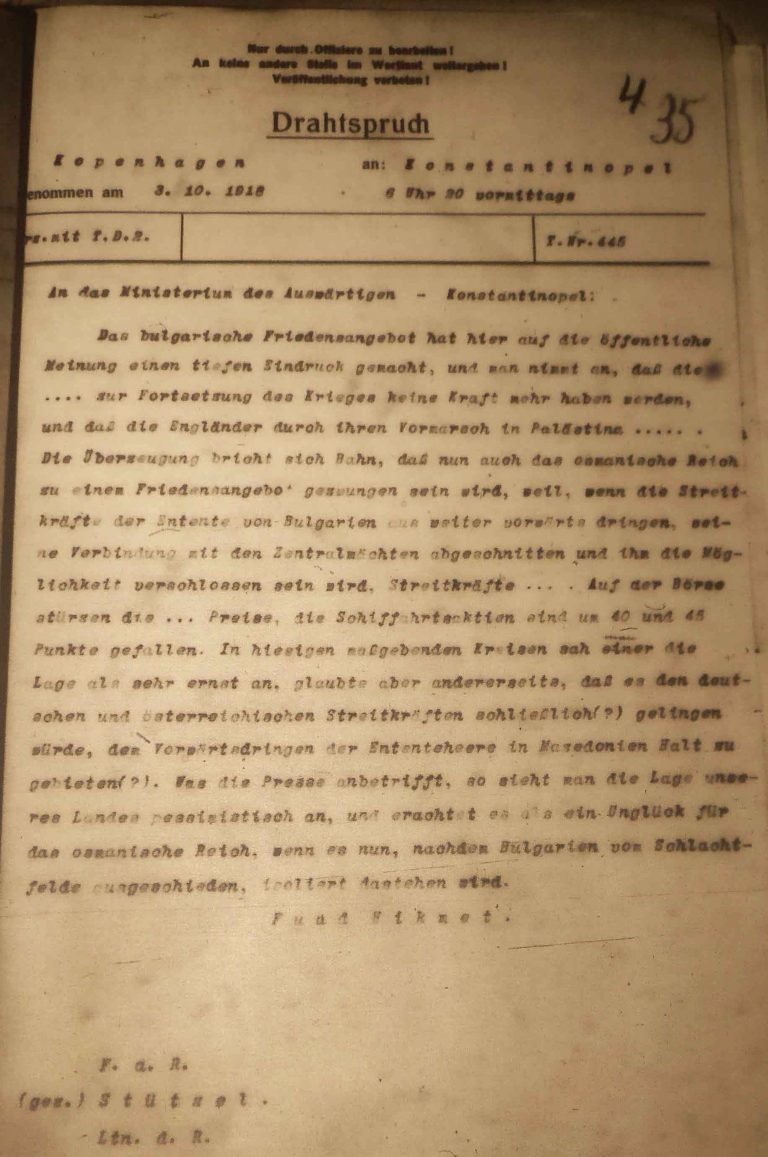

‘It is difficult’, Mark Sykes wrote in a memorandum on 26 September 1918, ‘to venture any anticipation of the effect [of Allenby’s victory] in Turkey itself.’ (CAB 24/145/27) It seemed to have been clearer in the mind of the Ottoman diplomats. On 3 October 1918, Fuad Hikmet – the Ottoman envoy in Copenhagen – wrote to the Ministry for Foreign Affairs that, after the British advance in Palestine and the armistice signed by Bulgaria in Salonica on 29 September, ‘It [was] now believed that the Ottoman Empire [would] also be compelled to accept a peace agreement.’ (GFM 21/407)

Fuad Hikmet, to the (Ottoman) Ministry for foreign Affairs, 3 October 1918 (catalogue reference: GFM 21/407)

Having been joined by T E Lawrence and Emir Feisal’s northern Arab Army, Allenby captured Damascus on 1 October 1918 and Aleppo on 26 October (WO 106/14). Four days later, on 30 October 1918, the Ottoman Empire signed the Armistice of Moudros on board HMS Agamemnon.

The war in the Middle East was over, undoubtedly precipitated by the devastating effects of the Battle of Megiddo. In the words of General Chaytor, ‘Such a complete victory [had] seldom been known in all the history of war.’ (WO 95/4732)

Notes:

- Revelation 16:14 and 16:16. ↩

I am interested in both World Wars and really appreciate your publications on the subject.

An intriguing read. My late maternal grandparents were part of Allenby’s intelligence team so may have had a part to play in the battle. My Mother and Uncles always said that their parents never spoke of their war service and it is a matter of pride to us that they were mentioned in dispatches for their efforts.

It was partially instigated to gain Haifa, where Abdu’l-Baha resided. The Turks had promised to kill him if they were ever forced to leave the area and this information was passed by various routes to Baha’is in London who petitioned the British government. Some notes of it are in the writings of Tudor Pole. I have just been reading “The Servant, the General and Armageddon”. As for ‘end of the world’ – that was a mistranslation because of confusion over the meaning of the Greek words ‘kosmos’ and ‘aeonos’ – see Kittel’s theological dictionary of the New Testament. It was amended in the New English Bible, published in 1970