The Four Courts complex in Dublin was destroyed on 30 June 1922, in the early days of the Irish Civil War. The Four Courts housed Ireland’s upper courts and it was here that the Public Record Office of Ireland (PROI) was located.

A six-storey Victorian building made of cut granite, it is strategically positioned along the River Liffey and was well-barricaded when the Provisional Government ordered Michael Collins, commander of the National Army, to attack the complex on 28 June. Over the next two days it was bombarded by heavy artillery and by 30 June, a fire had spread from the nearby Land Judges’ Court.

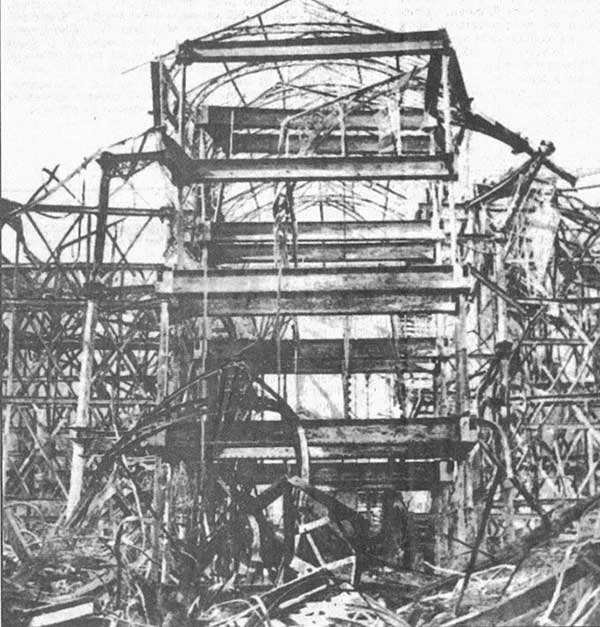

When two mines exploded in the Record Treasury at around 2pm, over 700 years of records were destroyed in an afternoon. As Herbert Wood, Deputy Keeper of the PROI wrote in 1930, “nothing but the four walls, roofless and windowless, containing a mass of distorted and tangled ironwork and debris, met the gaze when it was possible to get near enough to survey the scene.

“The rest of the contents had either been consumed by the intense heat, or, as happened with some of the records on the top storey, scattered by the winds of heaven over the city and suburbs, some being found on the Hill of Howth, seven miles distant from the city.”[1]

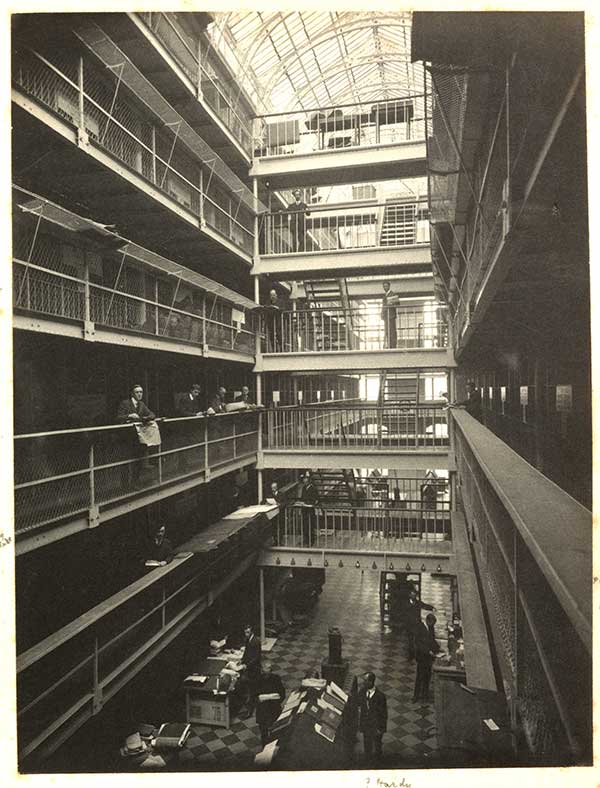

PROI Repository (1915) Copyright The National Archives (Dublin), Mills Album

Since the destruction of the PROI, many people have been under the assumption that the perished records were irrevocably lost.

Beyond 2022 is a digital humanities research project led by two academics from Trinity College Dublin. Dr Peter Crooks and Dr Séamus Lawless, along with their archival partners – The National Archives (UK), National Archives of Ireland, the Public Record Office of Ireland and the Irish Manuscripts Commission – have set themselves the task of digitally reconstructing the PROI building and its collections as they were on the morning of 30 June 1922.

Developments in digital technologies, alongside historical research and the approaching of the anniversary of the destruction have created the circumstances and the opportunity to virtually reconstruct, as far as possible, the archival holdings as they were in 1922.

The first phase of the project has seen the creation of a database of archival holdings based on Herbert Wood’s A Guide to the Records Deposited in the Public Record Office of Ireland (Dublin, 1919) and the Deputy Keeper’s reports of accessions in the subsequent three years.

With this as a foundation, it has been possible to identify replacement materials, many sourced from clerical copies, facsimiles, printed editions, published calendars summarising the contents, as well as original holdings from across the world.

The National Archives of Ireland, with the support of the Irish Manuscripts Commission, is also undertaking a conservation assessment of over 200 boxes of materials that survived the fire in order to determine what can be treated and made available to researchers and the public.[2]

The above video was produced for Beyond 2022, Ireland’s virtual record treasury.

The National Archives is able to contribute substantively to Beyond 2022 as it holds an extensive collection relating to the governance of Ireland, its people and its history from 1200-1922.

From 1199 the king of England exercised lordship over Ireland and matters relating to its governance are found recorded throughout the archive of the English administration.[3] Orders and responses on a vast range of business crossed the Irish Sea thereafter because the government in Dublin was required to account for its actions to the crown.

The National Archives’ Irish records include correspondence from the administration in Dublin, alongside the records of the Irish Treasurer, whose accounts were audited at the English Exchequer.

As the complexity and scope of the English government in Ireland expanded, so did the administrative and bureaucratic communications and The National Archives’ holdings include original correspondence, clerical copies of letters and accounts, as well as grants, petitions and commissions of office.

They now survive in bulk here and provide searing insights into aspects of everyday life, the economy, trade, warfare and government from the Middle Ages to the twentieth century.

Beyond 2022 has also provided the impetus to look again at the collections and try to unearth poorly catalogued or previously unknown material.

A good example are the letters patent, which were the sovereign’s expressed intentions and were issued open, or ‘patent’, with the Great Seal pendant. Representing the standard means of communicating royal business, they contain grants of land and money, appointments to office, pensions, pardons, power of attorney, treaties, proclamations, and letters of safe conduct, to give a few examples.

A full series was held by the PROI from 1302-1893. While their destruction represents a significant loss, an examination of the records for Charles II’s reign (1660-1685) has revealed that over 200 letters patent related to Ireland were enrolled in the English Chancery.While these represent only a portion of the PROI holdings, they go some way towards recovering the destroyed records.

As with any government body, considerable administrative paperwork was required to secure a patent, and The National Archives also holds the instructions to the Lord Chancellor’s office from the crown to draft and issue the instruction.

The National Archives C 66/2932, m. 17 (9 October 1660) Enrolled official copy of letter patent appointing Sir Maurice Eustace as Lord Chancellor of Ireland.

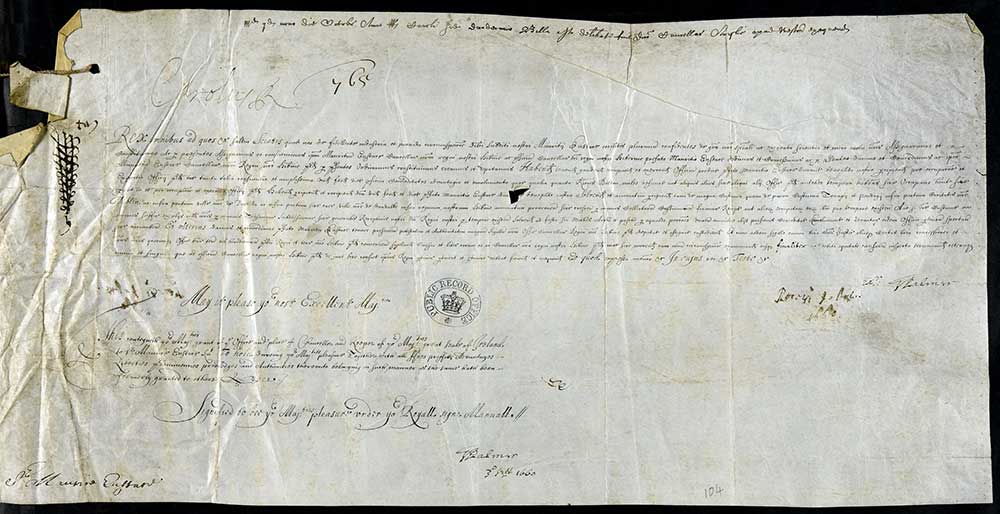

Above is an image of the letter patent appointing Sir Maurice Eustace as Lord Chancellor of Ireland in 1660, which includes his terms of his office, and below is an image of the order for this to happen.

The National Archives, C 82/2270, f. 104 (3 September 1660) Warrant (order) that the Lord Chancellor of England affix the Great Seal to a letter patent signifying the king’s pleasure in appointing Sir Maurice Eustace as Lord Chancellor of Ireland.

It is certain that detailed and systematic research will reveal a vast quantity of replacement material in the coming years.

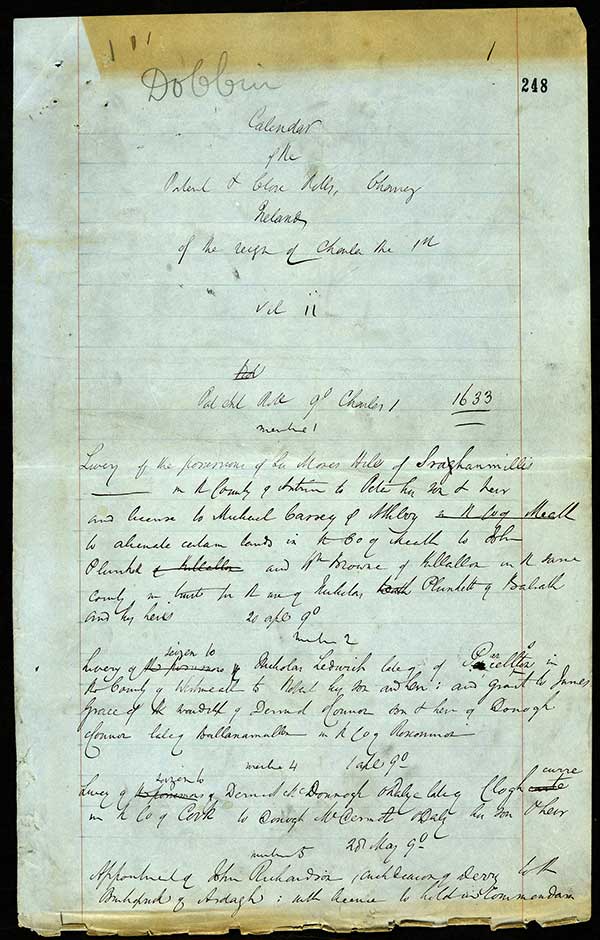

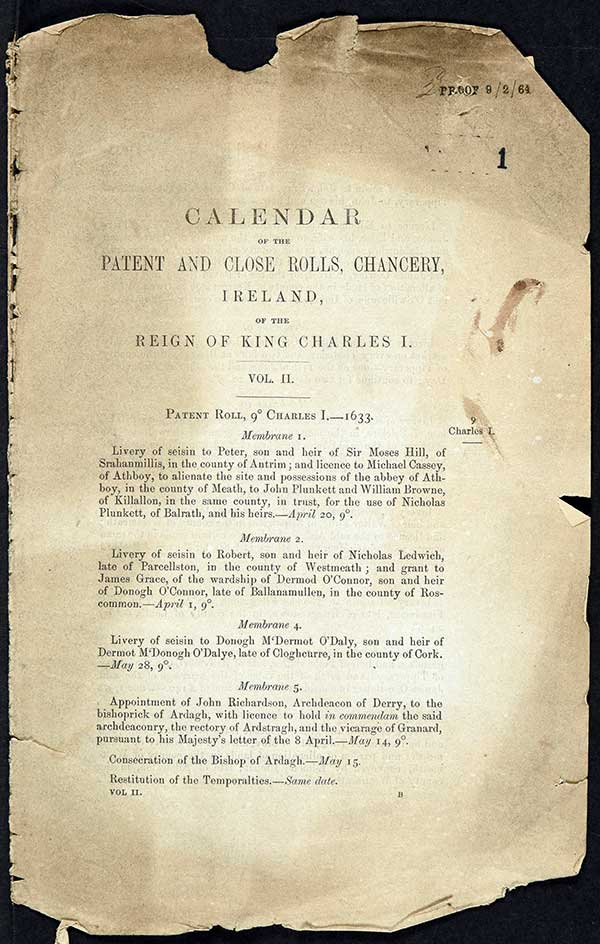

Another particularly exciting set of records are transcripts of destroyed patent rolls previously held by the PROI.

A project to transcribe Charles I’s patent rolls was undertaken in Dublin in the 1860s but ground to a halt in 1862 thanks to a legal battle over plagiarism.

Transcriptions of the original letters patent from 1632, as well as draft copies that had been prepared for publication, are held by The National Archives as the matter was referred to the government in London’s solicitors.

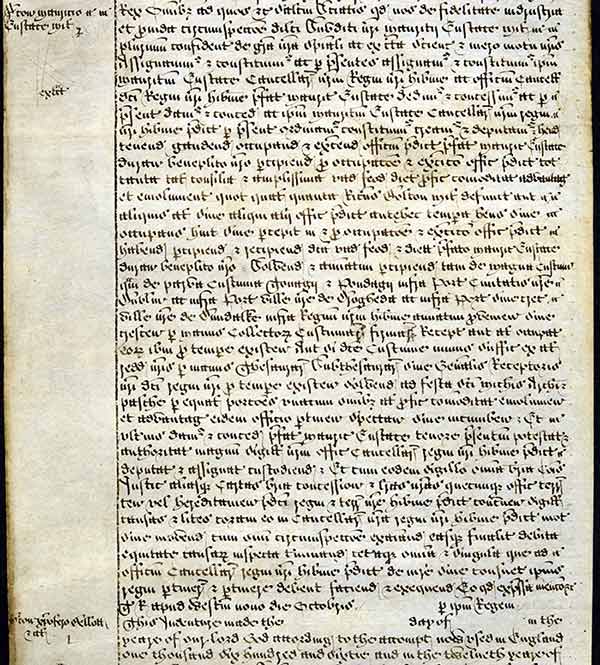

Transcript of the destroyed Charles I’s Irish Patent rolls (1633)

T 1/6535B Draft publication of Charles I’s patent rolls (1633) dated 9 February 1864

The above examples represent only a portion of the potential to digitally reconstruct the PROI’s holdings. As Beyond 2022 develops we will continue to blog and provide updates of research and work undertaken here at TNA.

For more details, see www.beyond2022.ie and @beyond_2022

[1] Herbert Wood, “The Public Records of Ireland before and after 1922”, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, vol. 13 (1930), p. 35.

[2] Twitter account of The National Archives of Ireland

[3] For background to the newly created kingdom of Ireland, see Stephen Church’s “Political Discourse at the Court of Henry II and the Making of the New Kingdom of Ireland: The Evidence of John’s title dominus Hibernie”, History, 102, no. 353 (Dec 2017), 800-823.

This major initiative is magnificent -with cooperation between sources in Ireland and the UK. No doubt some of this will be very relevant as we continue in the “decade of centenaries” (starting as some might say with the Great Dublin Lockout 1913, through WWI (1914-18), the Easter Rising and the slaughter on the Somme 1916 and of course from 1919 onwards, the Anglo-Irish War of independence (1919-21), partition and NI, the formal foundation of the Irish State (1922) and the tragic Irish Civil War (1922-23)).