This blog continues our series commemorating the centenary of the Battle of Vimy Ridge.

Following Britain’s ultimatum to Germany and the resulting declaration of war, the Dominion of Canada found itself de facto swept up in the turmoil. Such were the ties of Empire between Great Britain and Canada in August 1914. In Canada, few opposed Canadian participation in a “European war,” as it was referred to at the time.

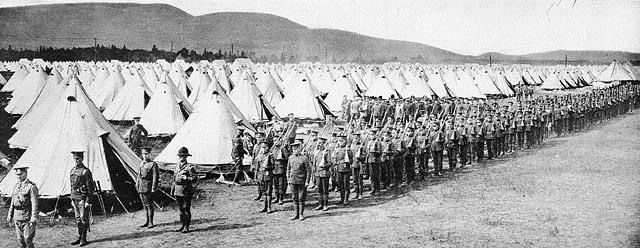

The First Canadian Army – a scene at Valcartier, 1914 (Library and Archives Canada – MIKAN 3642184)

The King accepted the Government of Canada’s offer of an expeditionary force. With a great deal of enthusiasm—and disorganization—the first Canadian volunteers were quickly sent to Valcartier Military Camp, hastily built about 30 kilometres north of Québec. In just over a month, the first Canadian contingent of about 36,000 soldiers and officers was ready to sail for England.

Canadian volunteers

Who were the first Canadian volunteers who agreed to serve “for the duration” under the British Army Act?

Almost all of the roughly 1,500 officers in the first Canadian contingent had received military training in the Canadian militia. More than two thirds had been born in Canada, while the others came from other parts of the British Empire. The proportion was reversed for the soldiers: over 65% had been born in other parts of the Empire, just under 30% were born in Canada, and the rest came from the United States and other allied countries.

By March 1917, when the army was preparing to take Vimy Ridge, the Canadian Corps had changed considerably. Since arriving on Salisbury Plain 30 months earlier, the Canadians had been through a trial by fire, facing the first poison gas attacks at the Second Battle of Ypres in April 1915 and fighting in the battles of Festubert (May 1915), St. Éloi (June 1916) and the Somme (July 1916). In 1916, Lieutenant-General Alderson had been replaced as Commander of the Canadian Corps by a new officer, Lieutenant-General Julian Byng.

Lieutenant-General Sir Julian Byng in May 1917. Photo taken by William Ivor Castle (Library and Archives Canada – MIKAN 3213526)

Byng was thus leading the Canadian Corps, which now consisted of four divisions. It should be noted that the 2nd Canadian Division included the only francophone battalion in the whole British Empire engaged at the front: the 22nd (French Canadian) Battalion (now the Royal 22nd Regiment). Created in October 1914, this battalion was commanded entirely by francophone officers; French Canadians were able to serve their country in their own language.

Attack preparations

Once Byng’s plan had been submitted, modified and approved by the military command, preparations began for the attack on Vimy Ridge. The Canadian Corps, which had been assigned this task, prepared for the assault with great determination and meticulous care. Byng had a scale model of the German defences made, and he used it behind the lines as he personally supervised the Canadians’ training. Every day, officers and soldiers practiced, as realistically as possible, the tactics that they would employ during the attack. They worked on timing their advances to follow, and benefit from, the artillery’s creeping barrage.

During this time, Canadian and British engineers had to prepare ammunition stores, water tanks and pumps. Twenty-five feet below the trenches, the tunnel system was expanded, to ensure that the troops could move toward the front-line trenches and that the communications network was secure.

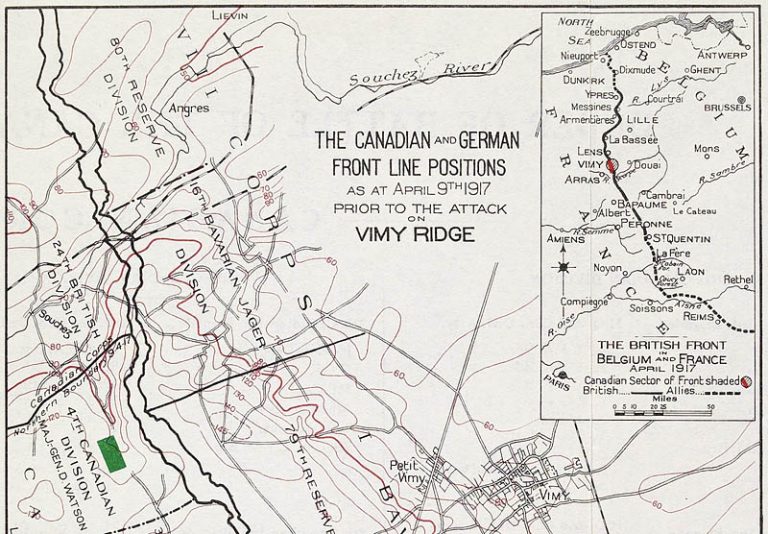

Map of Vimy Ridge on April 9, 1917, before the battle started (Library and Archives Canada – MIKAN 178969)

Royal Flying Corps pilots were tasked with observing German positions and bombarding key targets, such as railways and German airfields. The invaluable information that they gathered was relayed behind the lines and led to over 80% of the German artillery batteries’ locations being identified.

In the lead-up to the attack, the artillery began pounding the German trenches on 20 March. This bombardment continued until 2 April, when it reached its maximum intensity. It is estimated that more than 1 million artillery shells were fired during this preparatory period, with over 50,000 tons of explosives hitting the German positions. The damage to the German lines of communication from the artillery fire slowed the supply line to defenders in the front lines considerably.

Canadians advancing through German barbed wire, April 1917 (Library and Archives Canada – MIKAN 3404765)

On the day of the attack, the 15,000 Canadians who took part in the assault on Vimy Ridge were confident of achieving their objectives. It was a momentous day for the Canadian Expeditionary Force, which expected to clearly show its determination and effectiveness. Although the soldiers in the assault did not know it yet, it would also be a momentous day for Canada.

Related resources

- Files of the Canadian Expeditionary Force

- From Enlistment to Burial Records: The Canadian Expeditionary Force in the First World War

- Canadians and the First World War: Discover our Collection

- Images of Vimy Ridge on Flickr

Biography

Marcelle Cinq-Mars is a senior military archivist in the Government Records Branch at Library and Archives Canada. She has authored many books focusing mainly on the First World War.

This blog was developed under a collaborative agreement between Library and Archives Canada and The National Archives. Look out for the next blog in the series on Thursday 6 April.

Thank you for the informative article. We should strive to remember the brave soldiers who fought in the Great War, and the lessons that the war bequeathed to us as its legacy.