Today (midnight, to be precise) is the 50th anniversary of the enforcement of the Marine Broadcasting (Offences) Act which effectively outlawed the operation of pirate radio stations broadcasting to the UK from offshore ships or disused sea forts.

The National Archives holds some fascinating files concerning pirate radio, about which, more later. To begin with, I’ll set out the historical context.

Demand for pop music

Following the breakthrough of The Beatles in 1963 there was an explosion of new groups and singers – a British beat boom, with the emergence of the Rolling Stones, the Who, the Kinks, the Animals, Dusty Springfield and many more exciting new groups and artistes.

By 1964 transistor radios were becoming popular, particularly with teenagers: for the first time, radio had become portable (previously ‘the wireless’ was a bulky set containing electrically heated valves). So there was an increasing demand for pop music on the radio. But BBC Radio did not cater for this. The ‘Light Programme’ delivered a mix of entertainment, including comedy shows, but the pop content was limited. There were also restrictions (‘needle time’) on the amount of recorded music that could be transmitted on the BBC.

There was a gap in the market; it was filled by pirate radio stations.

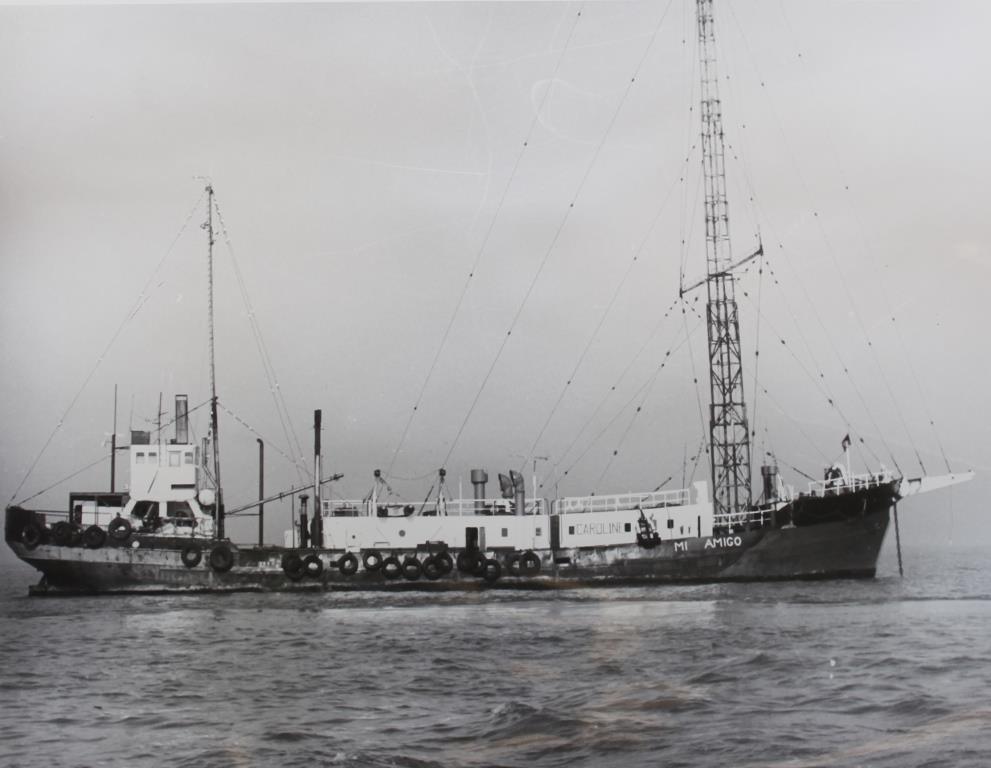

Still afloat in the 70s: MV Mi Amigo, Radio Caroline, 2 March 1976 (catalogue reference: HO 255/1235)

Exciting style

The first pirate radio station was Radio Caroline, founded by Irish entrepreneur Ronan O’Rahilly. It began broadcasting from a ship off Essex in March 1964. Over time several more offshore radio stations were established, including Radio London and Swinging Radio England. They broadcast from just outside English territorial waters.

The style of presentation on these channels was influenced by commercial broadcaster Radio Luxembourg and American radio stations. The DJs had a casual and spontaneous style (which contrasted with the formality of BBC presenters) and played the pop hits of the day. As the format developed, they increasingly used lively and exciting jingles, which were often created in the US. Several famous DJs, including Tony Blackburn and Johnnie Walker, began their careers on Pirate stations. There was a sense of romance about being out at sea, being frowned upon by the authorities, and broadcasting music to the people. These ‘pop buccaneers’ attracted hordes of fans.

Pirate radio also represented a business venture as stations frequently broadcast commercials for products and services, including well-known brands.

For the first time ever in the UK, pop music could be heard all day on the radio and the stations became very popular indeed. A Social Survey (Gallup) poll showed that over 6 and a quarter million adults out of a possible total of 19 million adults in the reception area had listened to Radio Caroline in the first three weeks of broadcasting in 1964.[ref]1. Pirate radio station, Radio Caroline. Note by Industrial Aids Limited Public Relations, 7 May 1964 (HO 255/1001)[/ref]

Government concerns

The UK Government expressed concerns about Pirate Radio at an early stage, and made it clear they wanted to prohibit them. Tony Benn, Postmaster General (1964-66) and Minister of Technology (1966-70), pressed the issue several times in the House of Commons.[ref]2. The Postmaster General, who headed the General Post Office, was responsible for the control of radio broadcast.[/ref] In a written answer given in the House of Commons on 4 February 1965 he stated:

‘The principal reason for taking action against the pirate stations is that they cause intolerable interference to the operation of broadcasting services in other countries and of certain maritime radio communication services in this country and abroad’[ref]3. ZHC 2/1213, Hansard, HC Deb 04 February 1965, vol 705 c328W[/ref]

Benn claimed that the wavelengths used by the pirates could potentially block emergency transmissions by ships at sea, and he cited evidence for this in the Commons on 22 March 1965:

‘the interruption of any of the authorised channels of communication between ships and the shore constitutes a danger to shipping. This was illustrated by the incident on 23rd February last, when a lightship was prevented for about 30 minutes from passing an urgent report to the shore because both of the frequencies available were blocked, one of them by a pirate broadcasting station.'[ref]4. ZHC 2/1217, Hansard, HC Deb 22 March 1965, vol 709 cc34-5W[/ref]

In my research I have yet to find a detailed set of arguments countering the government’s claims that pirate radio stations were blocking emergency transmissions. From the perspective of the pirates, the government’s fears were exaggerated. In his autobiography Johnnie Walker dismissed their claims as ‘government spin’.

Another criticism which Benn frequently advocated was that none of the stations were paying royalties in respect of copyright:

‘They are also stealing copyrights of all records they broadcast and stealing the work of those who have made the records and the legitimate business claims of those who manufacture them.’ [ref]5. ZHC 2/1216, Hansard, HC Deb 16 March 1965, vol 708 cc1058[/ref]

However, Johnnie Walker claims that ‘the pirate radio stations had always offered to pay royalties but the record companies refused because they didn’t officially recognise our existence’.[ref]6. Johnnie Walker, The Autobiography (Penguin Books 2008), p. 106[/ref]

Despite opposition to pirate radio from the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry, advance copies of new discs kept finding their way to the stations, thanks to record promoters, and record sales must surely have been boosted by all the airplay.

The Government takes action

The shooting of Reg Calvert, the owner of a fort-based pirate radio station (Radio City) in June 1966 brought bad publicity for the pirates and accelerated the government’s decision to take action to outlaw the offshore radio stations. The Marine Etc., Broadcasting (Offences) Bill was introduced into the House of Commons on 27 July 1966 and duly enacted.

The Act would come into effect at midnight on 14 August 1967 – it would now be ‘an offence for any British subject to broadcast, work for or advertise on, promote or assist any vessel, aircraft or structure that was involved in broadcasting to the British Isles from outside territorial waters’.[ref]7. Ray Clark, Radio Caroline: The True Story of the Boat that Rocked (The History Press, 2014), p. 149[/ref]

Archival sources

I have recently started research for a talk about Radio Caroline and the battle of the airwaves (part of an event at The National Archives called Pirates, Pop and Protest, on Saturday 7 October).

I’m still discovering material but I’ve already found some gems. The documents are fascinating because they show how closely the GPO (General Post Office) was monitoring Pirate Radio stations before and after the Marine Broadcasting (Offences) Act came into force. The monitoring was carried out mainly by a network of Post Office Radio Stations (I have found one example of a Post Office technical officer listening in on a receiver at a home address). The reports produced by GPO officials are very detailed; there is, for example, a list of advertisements broadcast on Radio Caroline with the dates and exact times of transmission.

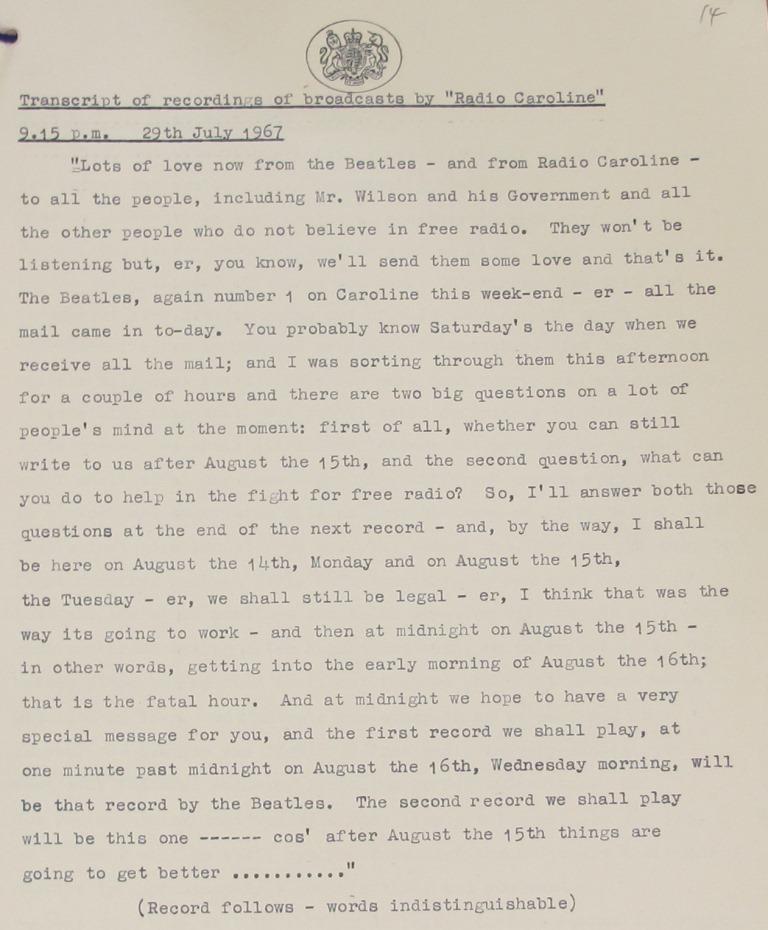

I am particularly fascinated by the transcripts of recordings of broadcasts by Radio Caroline, made as the deadline of midnight on 14 August approached, and the spirited messages of defiance from the DJs, such as this transcript from 29 July 1967, which I assume are the words of Johnnie Walker. The DJ gets his dates muddled (‘August the 16th’ should have read the ’15th’) but his pledge to carry on broadcasting past the legal deadline is clear:

‘at Midnight we hope to have a very special message for you, and the first record we shall play, at one minute past midnight on August the 16th, Wednesday morning, will be that record by the Beatles’

Transcript of Radio Caroline Broadcast, 29 July 1967 (catalogue reference: DPP 2/4434)

One by one the pirate radio stations closed down, apart from Radio Caroline (which had two operations: North – MV Caroline, off the Isle of Man – and South – MV Mi Amigo, off the Essex coast). Johnnie Walker describes continuing to broadcast past the midnight deadline on Radio Caroline (South) with his fellow DJ Robbie Dale on the night of August 14/15th. At midnight he played the classic protest song ‘We shall overcome’; after giving an assurance that Caroline intended to stay on air, he did indeed play ‘All you need is love’ by The Beatles. Walker writes:

‘Someone in the studio produced a bottle of champagne, the cork was popped and we all drank a toast to the future of Caroline, and then we sang along to The Beatles. I was on a complete high’.[ref]8. Johnnie Walker, The Autobiography (Penguin Books 2008), p.120[/ref]

Radio Caroline North and South continued broadcasting programmes to Britain and the continent until 3 March 1968, when the ships were silenced due to financial problems. They were towed to Amsterdam and impounded. Radio Caroline was revived, though it had ups and downs; it still continues on the internet and digital radio but that, as they say, is another story.

The BBC responded to the popularity of pirate radio by restructuring its radio services, establishing Radio 1, Radio 2, Radio 3 and Radio 4 on 30 September 1967, with Radio 1 as the pop music service. Several pirate radio DJs joined it. The heyday of pirate radio may have been brief, but it had a lasting impact on radio broadcasting.

Mark,

very interesting, is there any evidence the BBC pressurised/lobbied the Government on the issue?. I doubt that the BBC would have revamped their radio services if it was not for the stations like Radio Caroline, and we would still be listened to ‘The Light Programme’, no thanks. The attitude of the BBC (and the Government) at the time makes them sound like being in the 19th century, is there much evidence that the radio transmissions were being blocked on a large scale or as is often the case a few cases are used to create the picture of a major issue.

Thanks David for your interest. This blog post is based on the fruits of my research so far, but that research will be continuing, as I’m delivering a talk on the subject at the ‘Pirates, Pop and Protest’ event on 7th October (more details will be placed on our website about this soon). I’m planning to look into the issue of emergency transmissions being blocked in some more depth, though I suspect it may be difficult to come to a firm judgement about this.

Hi Mark

That all sounds very interesting, and I hope to be at the lecture.

I have been going through the archives looking at offshore radio history, over some years. Maybe you’d like to e–mail me privately and can give you more detail.

Chris

The claim the offshore stations blocked emergency services was rubbish.

When the Commercial stations began [ there were a large number ] all were allocated MW / AM frequencies.

Hello Mark.

I read that you “joined The National Archives in 1983” and that you “have recently started research for a talk about Radio Caroline and the battle of the airwaves (part of an event at The National Archives called Pirates, Pop and Protest, on Saturday 7 October).” You also add that you are “still discovering material but I’ve already found some gems.”

Perhaps, before venturing forth you should contact Chris Edwards who has from time to time over many years, almost made the Archives at Kew his second home. He is the British editor of Offshore Echos magazine, an international publication that is one of the most reliable sources of research into this subject. I add this suggestion because in your blog you begin by restating a classical myth:

You wrote that “The first pirate radio station was Radio Caroline, founded by Irish entrepreneur Ronan O’Rahilly.” The problem with this statement is that it is totally untrue based upon more than one factor. First, it was not the first British pirate station (so-called), or even the first offshore station.

In your research at Kew you must have come across the remark by one MP that Ronan O’Rahilly was a mere “decoy duck” for sponsored commercial broadcasting interests. Ronan O’Rahilly did not found Radio Caroline, and his pedigree which you state is “Irish”, conceals the fact that his father was born in Hove, England, and his mother was born in the USA. True, Ronan was born in Ireland, but after about 1960 he decamped in London, England.

You also state that: “Radio Caroline North and South continued broadcasting programmes to Britain and the continent until 3 March 1968, when the ships were silenced due to financial problems. They were towed to Amsterdam and impounded. Radio Caroline was revived…” That is also untrue. The two Caroline stations ceased their original operation at midnight on August 14, 1967 and what followed was more mythology. The original Radio Caroline was never revived after midnight on August 14, 1967.

Radio Caroline was not the “instant” by-product of a pop music marketplace, the BBC had already been promoting that market and The Beatles were already well on their way to soaring popularity. The first programs on Radio Caroline were of a type regularly broadcast and announced in “BBC form”, they were not rock and roll shows hosted by disc jockeys.

The early tape recorded programs were made in the studio of its supposed rival (Radio Atlanta, which in reality was part of the same operation before Radio Caroline ever broadcast a sound! The “merger” story was another myth, because there was only one project with two ships serving two purposes, as well as geographical locations.) I am have all of Tony Benn’s diaries, along with the writings of many other political figures of the time. None of them dared tell the truth, and I am not sure that Benn was aware of the real story which was concealed within the same censorship that the Boothby-Driberg-Kray affairs also sought to cover-up, and which the Daily Mirror partly discovered at great financial cost. Because once that thread is pulled upon it winds up in the British Royal Family. Another thread winds up with CIA interests in Houston, and another related strand leads to Dallas, Texas and events surrounding the Kennedy Assassination.

The folks calling themselves “Radio Caroline” today have in some ways created for themselves a secular cult by borrowing the methodology of religion. There is absolutely no connection between what they are doing now and what transpired between 1964 and 1967. All they have is a name which is about as common in broadcasting as Smith, Williams, and a host of other monikers.

My own active interest in this research began as a casual but published freelance reporter back in 1966, and along the way I interviewed key people such as Allan Crawford and Bill Weaver (who had legal and physical control of the mv Mi Amigo in Texas), as well as working with Don Pierson (Radio London; Radio England and Britain Radio), who gave me his legal and financial records about how he came to create those stations. I also worked with Ben Toney (a key programmer associated with several of the offshore stations. Ben stayed in my home in Texas during the attempted offshore revival of Radio London in 1984, and its syndicated US broadcasts over Mexico’s XERF and local stations in Texas.

On August 15 of this year, I authored a major feature for a British newspaper about this subject called ‘Radio Caroline and the Kennedy Hoax’ as the prelude to publishing a series of books on the subject that will begin release later this year. A related web site (due for updating very shortly), is at dial999forcaroline.com .

I should also add that in addition to working closely with people like Chris Edwards – whose dedicated and thorough work of research I respect, one of my ‘fact checkers’ is a man now senior in years, who was in 1964-1966, the senior radio broadcasting engineer on the Mi Amigo, and who also worked at correcting the technical errors made by others on board the mv Fredericia (renamed Caroline) when it was anchored off the Isle of Man.

Mark, because you work for the National Archives, I thought that it would be wise to give you a “heads up” regarding the minefield of misinformation, lies, distortions, pretense and sheer nonsense of dj puffery that you have announced that you intend to walk into. This rubbish has to date been published in a wide variety of books. But since the date of your announced talk has no particular relevance, might I suggest that you postpone this scheduled event while you peek behind the proverbial curtain where you could discover the real story?

It is more surprising and explosive than anything you have read to date.

Mervyn

Dear Mark

I read this post with great interest. I am currently researching film and cinema advertising in the 1960s and was wondering if there is evidence of particular movies and/or cinema chains advertising on the pirates in the list of advertisers you mention.

Best wishes

Richard