In part one of my blog post on records held by The National Archives on sex work and sex workers, I focused on why we have these records and the problematic historic language that is often found within them. In this blog I will explore further why this is, and how we can work to reclaim the voices of sex workers in the records.

Agency and personal voices

Within the records of government, sex workers lack agency. As with most of our records the voice of the state dominates and frames the narratives, especially of anyone historically more marginalised[ref]There are many examples of this in our collections; some of The National Archives’ richest records around black and ethnic minority history and LGBTQ+ history tend to come from records around policing.[/ref].

While the voices of sex workers can be heard in the archives, rarely are they speaking freely or speaking on their own terms. While there are, as there always have been, many reasons why people engage in sex work, this is often framed by shame or a ‘victim’ status in our records. Similarly, items in our collections often use passive language, such as ‘treatment’, ‘imprisonment’ and ‘rehabilitation’.

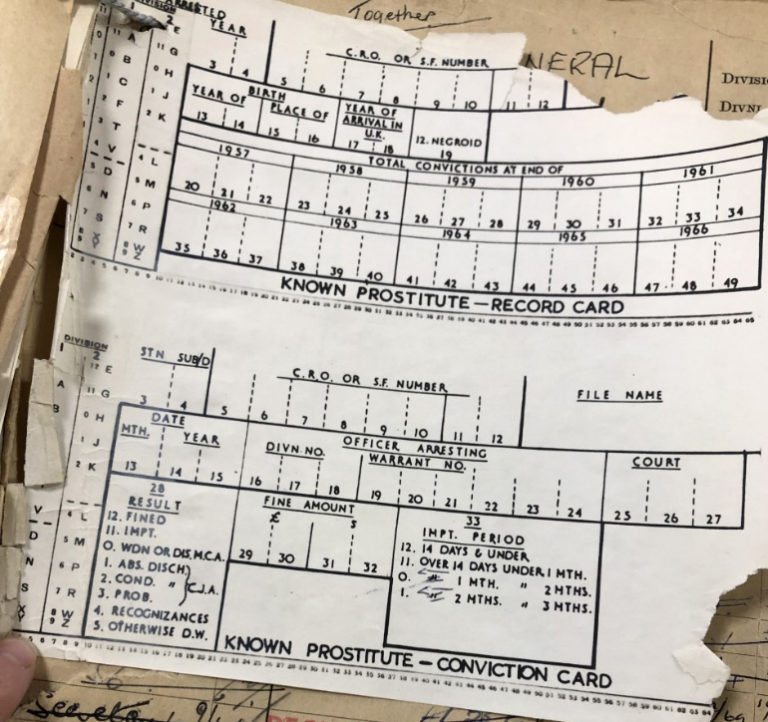

Statistics and graphs relating to sex work are common, rather than items highlighting the personal experience of individuals. Opinions on sex work were often requested or sent in to government, but rarely are the views of sex workers themselves taken in to account.

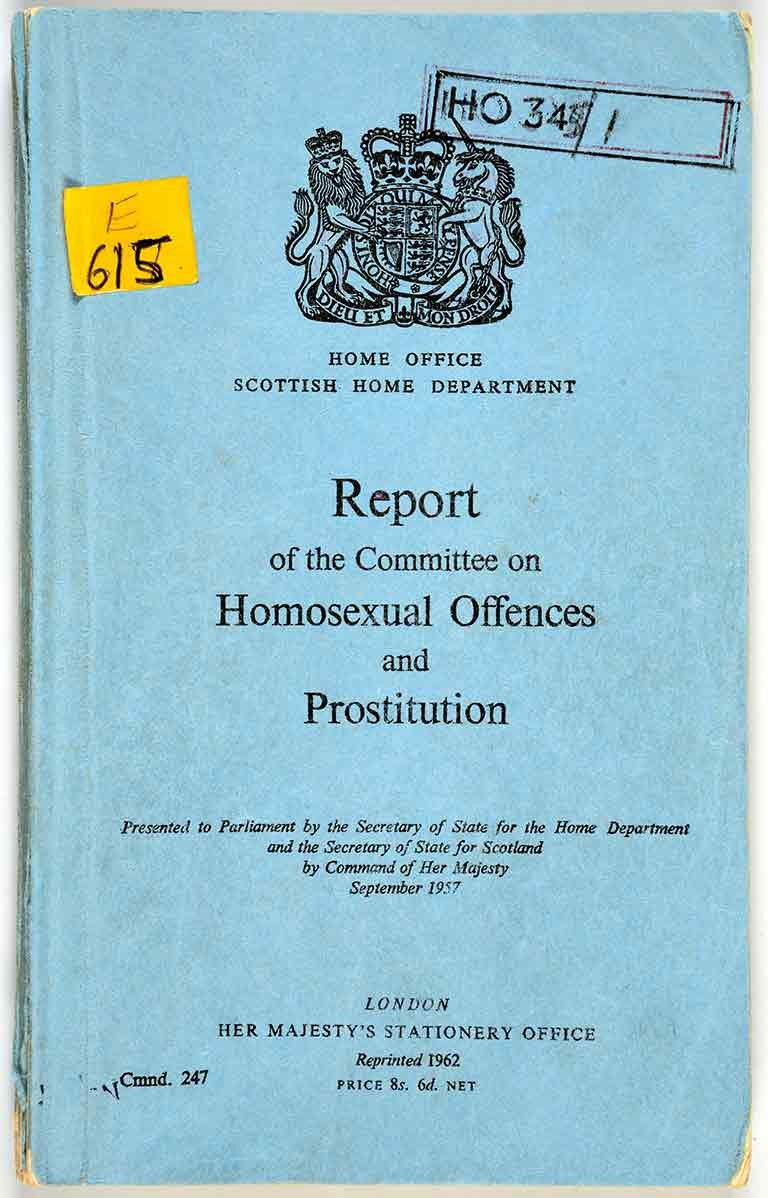

Reforms have been proposed in relation to sex work, notably in the 20th century through the Wolfenden Committee and Report. This committee is known predominantly for its progressive influence on the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality in England and Wales. However, it was convened initially to address concerns about the increase in sex work.

Various people were consulted by the Wolfenden Comittee to inform this change in the law, including the views of the Church of England Moral Welfare Council, the Association for Moral and Social Hygiene, and representative women’s organisations, but sex worker voices are notably absent, despite how the change in the law would ultimately have a huge impact on their lives.

This is a classic example of sex worker voices being missing from the records, reflecting their lack of consultation in government discussions from the era. As Julia Laite has noted, unlike the outcome relating to homosexuality between men, the resulting Street Offences Act of 1959 made the law more punitive towards sex workers than at any other time in UK history[ref]’Common Prostitutes and Ordinary Citizens: Commercial Sex in London, 1885-1960′ by Julia Laite.[/ref].

Against the grain

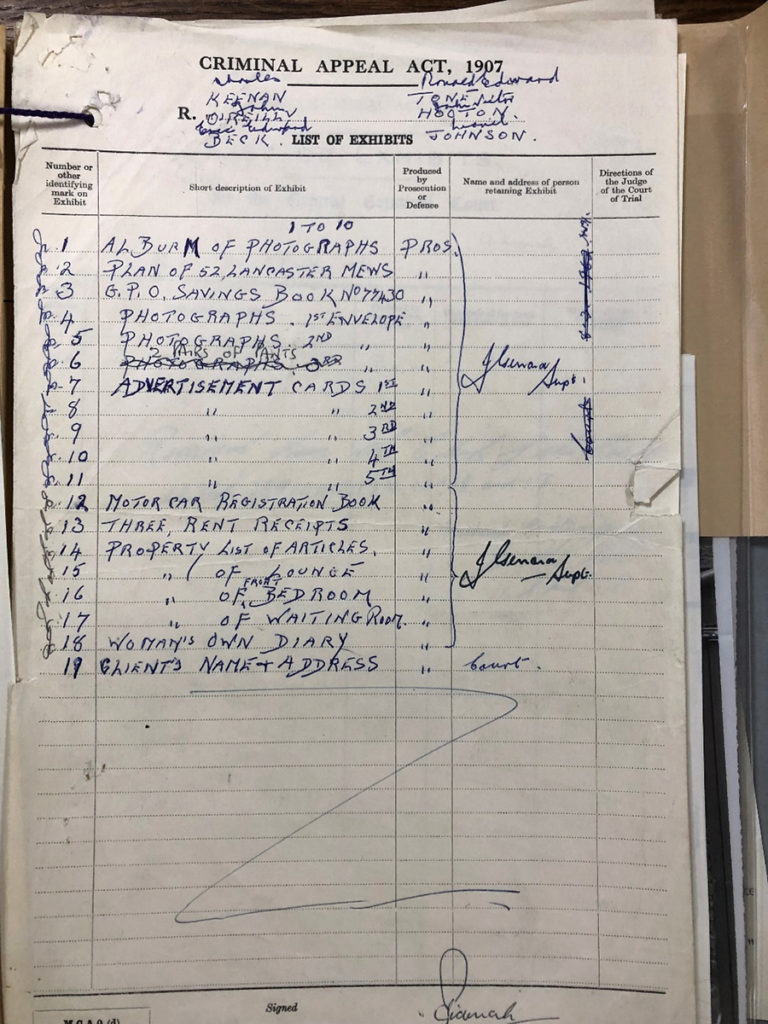

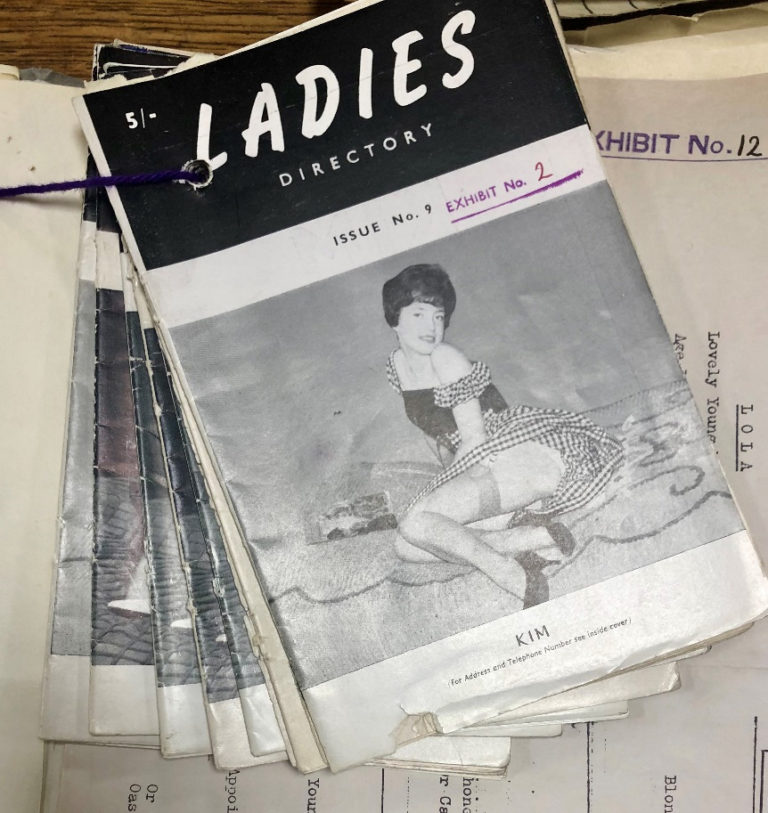

Despite this, where items are seized by police or sent into government, we can start to hear the voices of past sex workers and understand more about their lives; greater personal insights can be gained.

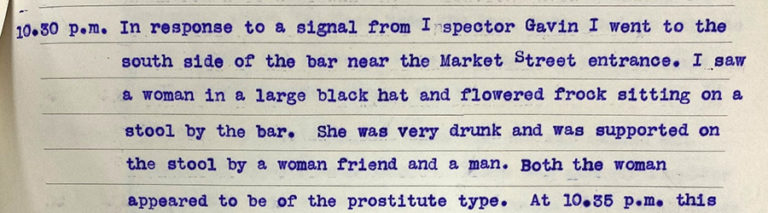

At times, voices are verbatim-recorded after arrests or through undercover policing; seized publications or newspaper articles record more first-hand viewpoints; and directories advertising sex worker services provide a different perspective.

While each of these sources may have their own complex origins and potential biases, they allow us to start to draw out the more ‘hidden’ voices of the sex workers in our archives[ref]This has been completed with limited document access during lockdown and will be expanded eventually with a fuller range of examples.[/ref].

In general such items are in the context of arrests and policing, but can be read against the grain to give a more revealing insight into past sex workers’ lives. Despite the complexity and potentially problematic nature of these records in these two blog posts, I believe there is a lot to be gained from these records.

Reclaiming the records

I am exploring two approaches to work with such records, to keep the integrity of the original records but to mitigate and supplement some of their more problematic areas.

- One is key to this fellowship: exploring working with current sex workers to add modern opinions and interpretations to sit alongside these historic government records (for example, in event or exhibition formats). The hope is that this would start to redress the power dynamics of those whose voices have historically been recorded.

- Another approach I am exploring to complement this is to put government records alongside those of other institutions, which reflect different perspectives. This could mean placing our records alongside ‘tart cards’ at the Wellcome Collection or the records of the English Collective of Prostitutes at Bishopsgate Institute – uniting collections to tell a fuller narrative.

Both approaches are designed to add balance and nuance to the interpretation of archival records.

The fellowship continues

By working with current sex workers we can start to reclaim the agency and voices of individuals that have at times been lost from these records. Sex work remains one of the most debated and controversial topics in modern society, and these archival records can be used as a point of reflection for how sex workers have been treated, marginalised and silenced in the past. These records offer excellent opportunities for debate, discussion and learning.

Through a combination of collaboration and reading records against the grain, we can use the starting point of state records to reflect on historic sex work. Using the time honoured feminist tradition of reclaiming words that have been used against us, we can reclaim the voices and experiences of past sex workers, from records in which their voices were traditionally silenced or hidden.

Eventually I hope to experiment with language and agency in the records in quite a literal and physical sense. The intention is to create copies of archival records and use zine-making sessions to play around with the words and language in the records – working with current sex workers, who can tell their own stories, subverting the purpose of records that historically ignored their perspective.