Content note: this blog contains references to dehumanising treatment of trans people, intrusive medical details, and systemic transphobia. At times, the records contain uncomfortable and offensive language and content. Some of the original language and legal terms are preserved here to accurately represent our records and to help us fully understand the past.

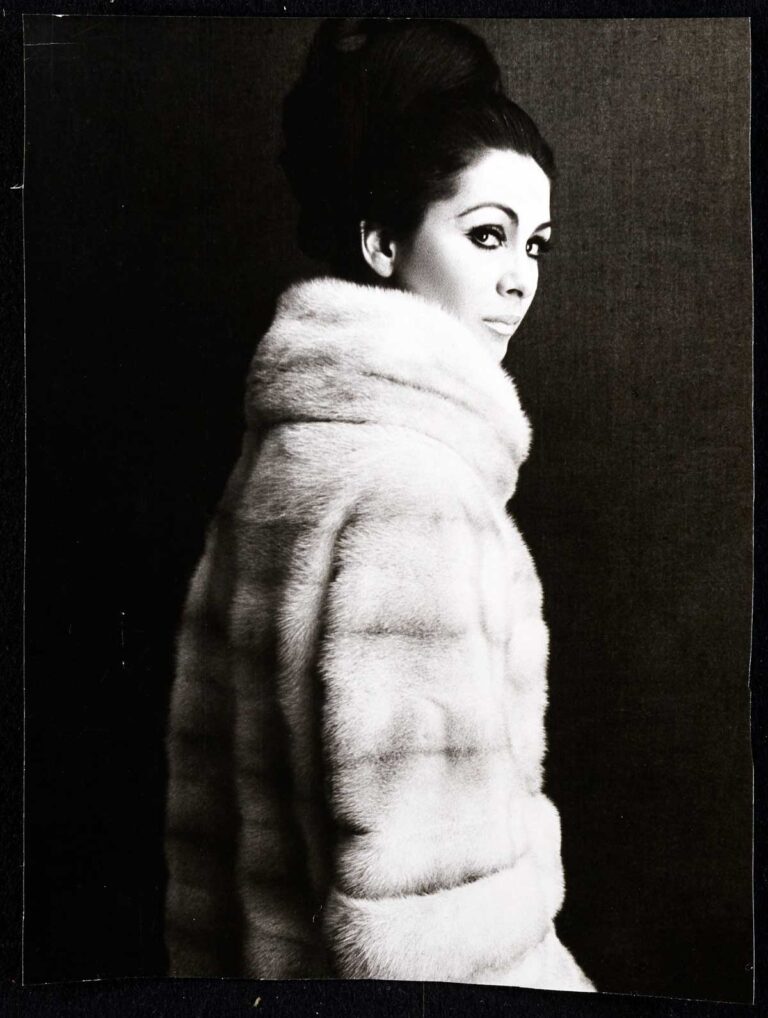

Our previous blog about April Ashley explored her early life, work as a model and how she met Arthur Corbett. Here we will explore the explosive divorce case that followed.

In this blog I have tried to give April agency, at times telling the story in her own words. The records we hold reflect the legal, state perspective, which at the time was largely unsympathetic to people whose gender identity differed from the sex they were assigned at birth. The focus of this blog is on the court case, because the records we hold about April largely exist because of this, and due to its subsequent impact on trans people in the following decades. However, April was so much more than this case, as the wider story of her life, in the preceding blog and this one, shows.

Corbett vs Corbett

The Honourable Arthur Corbett sought an annulment from April Ashley (see footnote 1). April had tried to seek maintenance, which Arthur countered by arguing it was not a valid claim, because the marriage itself was unlawful. Divorce by mutual consent was not possible until a few years later, so Arthur went to the courts. He attempted to get an annulment on the basis that April was legally male and had demonstrated ‘incapacity or wilful refusal to consummate’ their marriage. April countered on similar grounds of unconsummation (see footnote 2).

This must have been a blow to April. Arthur knew about April’s assigned gender at birth, had helped defend her from the press attacks a few years earlier, and was attracted to April partly because of her gender identity. If they had sought to end the marriage a few years later, it is likely that divorce by mutual consent would have been agreed and the devastating aftershocks of the case would have been prevented. The centre of the case became whether or not the court legally considered April to be male or female. In the eyes of the law, was this a case of two men marrying? (See footnote 3.)

This was a key time in trans history. In 1966 the Beaumont Society, supporting ‘male to female’ trans people, had been formed. Just before April’s trial in July 1969 the First International Symposium on Gender Identity had taken place. Trans issues were gaining visibility, but visibility meant a backlash. Our files include a press cutting from 1965 with the headline ‘1,000 sex changes in 20 years’, showing that some were fearful of what it would mean for society if Ashley were declared legally female (see footnote 4). The legitimacy of trans lives was about to be challenged in a very public forum. Such cases always attracted press attention, but this one even more so, as April was a public figure moving in social circles with the rich and famous, and Arthur was connected to the aristocracy (see footnote 5). It had all the makings of a front-page news story.

The judge was announced as Justice Roger Ormrod, who had a medical background. This initially pleased April and her friends, but they were in for a shock (see footnote 6).

The case opens

On 11 November 1969, the case began. April was careful about what she wore and how she presented herself; not hyper feminine, as to appear fake (see footnote 7). From the start of the case it was decided she would be referred to as Mrs Corbett, not April Ashley – the name she went by.

The case was significant, as Ormrod noted:

‘It appears to be the first occasion on which a court in England has been called on to decide the sex of an individual and, consequently, there is no authority which is directly in point.’

Judgment: Corbett v Corbett (otherwise Ashley)

Over seventeen days, April’s body and mind were forensically scrutinised in an attempt to determine her legal sex. April was not treated like a person with feelings; she described the process as ‘utterly heart-breaking and humiliating’ (see footnote 8). Arthur and April’s background couldn’t have been more different. April felt there was class prejudice in court, protecting the establishment, rather than working-class April.

Arthur put on a show for the courts; he was frank and confessional. As someone who cross dressed himself, Arthur presented himself as deviant but repenting. April, by association, was seen as deviant but unrepenting, later writing: ‘I was not apologising for being myself’. Ormrod meanwhile would not meet April’s eye in court. April lost sympathy and support; she was seen as a corrupting influence on Arthur (see footnote 9).

Sex on trial

The court sought to determine April’s sex based on what were considered at the time – from a biologically essentialist perspective – to be key attributes:

- Chromosomal factors

- Gonadal factors (presence or absence of testes or ovaries)

- Genital factors (including internal sex organs)

- Psychological factors

She was subjected to a series of physical and psychological examinations, where her body was measured and even x-rayed (see footnote 10). Zoë Playdon described this all as ‘pseudo-medicine’ (see footnote 11). April was forced to confront her childhood and pre-transition body in detail. This evidence was used by Arthur and April’s defence teams.

Large sections of April’s and Arthurs case files, J 77/4532 – J 77/4537, are closed to the public. The case gathered lots of personal, invasive medical evidence on April’s biology and gender. What is open of the files reveals some of the literature that informed the case. This includes a lecture by pioneering sexologist Harry Benjamin entitled, ‘Transvestitism and Transsexualism in the Male and Female’, reprinted by the Albany Trust LGBTQ+ charity in 1967. The article acknowledges, ‘This subject is largely unknown and is still an almost unexplored field in medicine.’ (See footnote 12.) This is the context the court case was operating in when deciding April’s fate, and that of many trans people over the next decades – one of limited expertise. Other literature in the file includes an article on chromosomes.

April was being judged on biological factors, rather than how she felt. Her legal team argued she was medically intersex. In the psychological tests she was determined to be ‘transsexual’ – the only category of tests that acknowledged any sense of her gender not aligning with her assigned sex at birth. The Turner-Miles questionnaire was used and strongly scored her as female, but unfortunately was not administered in a way that was admissible in court (see footnote 13). Whether April was able to consummate the marriage was also discussed in intimate detail.

A precedent withheld?

A precedent case had actually taken place just prior to this that could have significantly helped April, but it seems it was suppressed. Sir Ewan Forbes had lived his life as a man, but had been assigned female at birth. Ewan was able to use his connections as a doctor to get his birth certificate updated to reflect his true gender. This made him inline for the family’s baronetcy, as a male heir, but this reregistration of his birth was contested by his cousin John. The court found in Ewan’s favour.

Details of the case were uncovered by Zoë Playdon, academic and LGBTI advocate, who discovered that April and her legal team were made aware of the case but were prohibited from mentioning it. The cases even had some of the same medical advisors involved. Although, as a Scottish ruling, it would not have set a direct precedent in England and Wales, it would have been a significant legal judgment to refer to and meant Ormrod would have had existing legal and medical evidence to consider (see footnote 14).

The verdict

The judgment was delivered on 2 February 1970, after an agonising wait of several weeks. The court determined that April’s legal sex was male, setting the precedent that sex assigned at birth was an individual’s legal sex no matter how they identified, or what medical treatment they had had. In the final judgment Ormrod made harsh comments about April’s voice and appearance; he also used male and female pronouns (see footnote 15).

It seems that trans people were tolerated, and even accepted, until their existence seemed to question the foundations of society – such as marriage, religion and class.

Legal recognition

Although Ormrod had specifically set out to determine legal sex in the context of marriage only, this case became the precedent for determining legal sex overall. As a result of Ormrod’s decision, the correcting of birth certificates for trans and intersex people ceased. Any interactions that required a birth certificate outed the birthnames and assigned gender of individuals, often forcing people to share incredibly personal details with people they had just met, such as for pension purposes, mortgage applications or job interviews (see footnote 16). It also held symbolic power, meaning vital documents were in names and genders that no longer reflected their true selves. April described it as a ‘legal limbo’ (see footnote 17). Not only did this judgment affect the UK, but it became a super precedent affecting cases globally, ‘disenfranchis[ing] trans people worldwide’ (see footnote 18).

Our records show a significant shift in approach across government departments after Corbett vs Corbett, with press cuttings and copies of the ruling included in correspondence. This judgment affected people’s pensions and National Insurance contributions, and raised questions around nationality and potential employment with government departments or in the armed forces (see footnote 19). More broadly, April’s trial felt like it questioned the legitimacy of all trans people – affecting public treatment of trans people and their reporting in the press.

April later said she wished she had appealed, but it had already been an intense and exhausting process. She was granted legal aid for the initial trial but not for an appeal (see footnote 20). Little was April to know the sweeping consequences of the case. Despite the traumatic, dehumanising experience in court, April said ‘this courtroom catharsis was a new beginning’ (see footnote 21).

She was to see Arthur again, on his death bed. He apologised to her (see footnote 22).

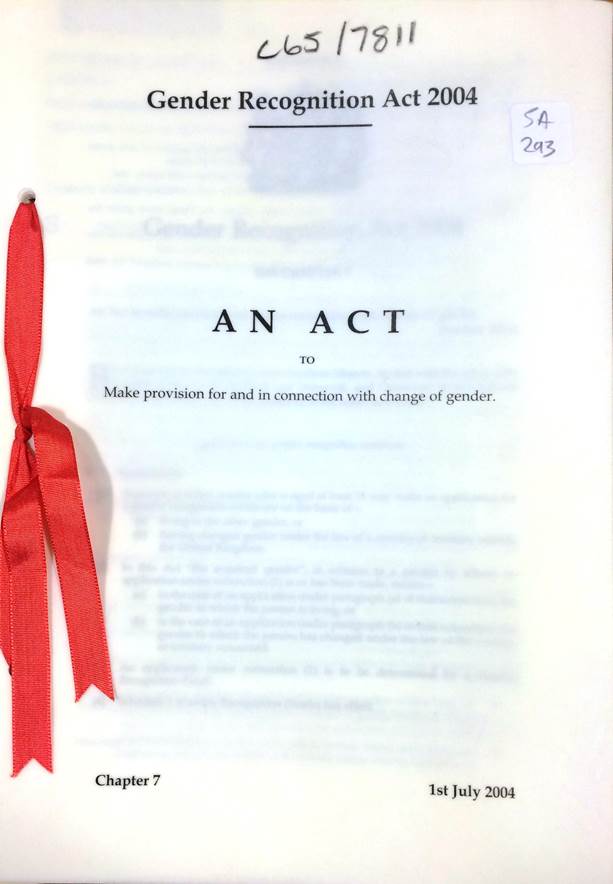

Gender Recognition Act 2004

The precedent set by April and Arthur’s annulment was to stay in place for several decades. The Gender Recognition Act (2004) changed things, entitling people under certain circumstances to change their legal gender, subject to a panel process.

This act is now considered by some to be outdated and in need of reform, but was a step forward at the time. April’s solicitor, Terrence Walton, was involved in the initial Private Members’ bill that was partially recycled into the eventual act (JA 538/126). Many people were involved in this legal change (and many campaigners wanted it to go further), from pressure group Press for Change and the Parliamentary Forum on Gender Identity, to the European Court of Human Rights. April repeatedly wrote to government representatives to change the law. She personally appealed to John Prescott, whom she had boarded with in her youth.

In 2005 the Gender Recognition Act became law, just days before April’s 70th birthday. April finally received legal recognition of her true gender.

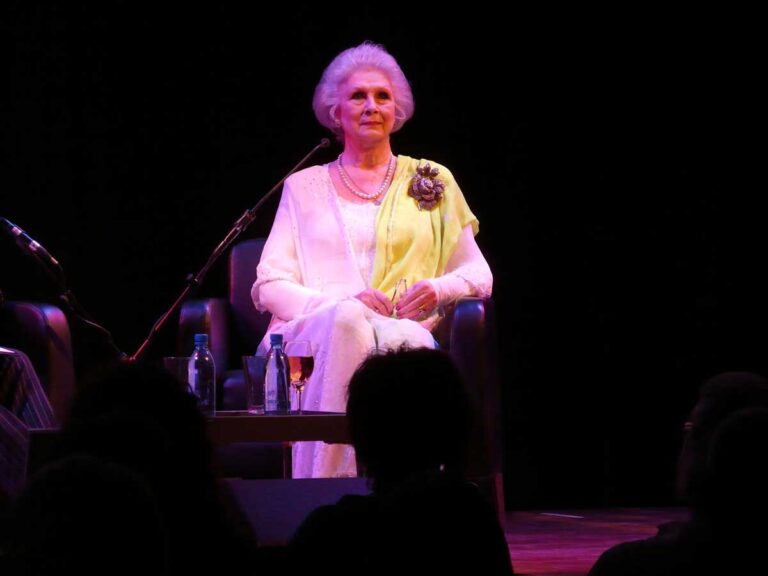

April Ashley MBE

In 2012, April received an MBE for ‘services to Transgender Equality’. In 2016 she was awarded an Honorary Degree by the University of Liverpool for this work.

April died in December 2021, at the age of 86. She lived through a lifetime of change, positive and negative, for trans people. April left a legacy of visibility, campaigning and pride.

Many people who are part of trans history do not have their voices heard in their own lifetimes. April was an exception; she lived in a time where she was able to tell her own story. Read more in her co-authored books, April Ashley’s Odyssey or The First Lady.

Footnotes

- This blog content is largely based on the Judgment: Corbett v Corbett (otherwise Ashley). February 1970, Ashley, April; Thompson, Douglas, The First Lady (London, 2006) and The National Archives’ divorce files. No direct accounts from Arthur Corbett are known to exist, although summaries of his testimonies are mentioned in the court report.

- Judgment: Corbett v Corbett (otherwise Ashley). February 1970.

- This was far before Equal Marriage and Civil Partnerships. Same sex acts between men had only just been partially decriminalised.

- J 77/4536, The National Archives.

- Later cases would protect anonymity, but not at this time. P v S and Cornwall County Council.

- Ashley, April; Thompson, Douglas, The First Lady (London, 2006). p.266.

- Ibid. p.267.

- Ashley; Thompson, The First Lady. p.262.

- Ibid. pp.275-280.

- Judgment: Corbett v Corbett (otherwise Ashley).

- Playdon, Zoe, The Hidden Case of Ewan Forbes: The Transgender Trial that Threatened to Upend the British Establishment (London, 2021). p. 302.

- Harry Benjamin, ‘Transvestitism and Transsexualism in the Male and Female’ reprinted 1967. J 77/4536, The National Archives.

- Judgment: Corbett v Corbett (otherwise Ashley).

- Playdon, The Hidden Case of Ewan Forbes.

- Judgment: Corbett v Corbett (otherwise Ashley).

- Burns, Christine (ed.) Trans Britain: Our Journey from the Shadows (London, 2018) shares experiences of trans people facing these barriers and the fight for legal recognition.

- Ashley; Thompson, The First Lady. p. 367.

- Playdon, The Hidden Case of Ewan Forbes. p. xiv.

- HO 213/2447, BN 88/291, PIN 43/590, PIN 61/27, JA 538/126, The National Archives.

- Hutton, Christopher, The Tyranny of Ordinary Meaning, Corbett v Corbett and the Invention of Legal Sex (2019), p.84.

- Ashley; Thompson, The First Lady. p. 279.

- Ibid. p. 356.