Content warning: this blog contains references to systemic transphobia, gender dysphoria and suicide. We recognise our records contain words that are at times offensive, however some of the original language is preserved here to accurately represent our records and help us fully understand the past.

April Ashley (1935–2021) was a pioneering model, socialite, and key figure in trans history. She is now well known for being outed in the press in the 1960s, for her precedent divorce case and for her work towards transgender equality.

This blog will explore April’s early life. It is mainly based on April’s testimony in her autobiography, The First Lady, alongside complimentary archival material, centring April’s own words and life experiences (see footnote 1). We will follow it up with a second part focusing in particular on her high-profile divorce in 1970, which was to affect trans people’s lives for a generation.

Early life

April was born in 1935 to a large, Catholic family in Liverpool. At birth she was assigned as male, or as she put it, ‘I was born a boy’ (see footnote 2). Her start in life was very different from the later glamour she surrounded herself with, having been brought up in the deprived dock area of Liverpool on Pitt Street. The housing here was in a state of disrepair and the family moved shortly after this. Our records show April aged 4 on the 1939 Register living with her father, a seed oilcake labourer, her mother and several other siblings at Teynham Crescent (see footnote 3).

April had a hard upbringing, being unfairly treated by her mother and suffering from calcium deficiency which required regular hospital treatments. April was also conflicted about her gender identity from an early age. As a child, she felt ‘if I was to live it could only be as a woman.’ (See footnote 4.)

April was desperate to escape her lonely, impoverished life. She had spent years watching members of her family heading off to sea, including her father. In an attempt to fend off her feeling of being a woman, she followed in their footsteps, seeing it as, ‘one of the things that made you a man’ (see footnote 5). April trained on the SS Vindicatrix and by 1952 was sailing on the SS Pacific Fortune to America. Our records contain April’s sailors pouch from this period, describing her as having brown hair, brown eyes and a fair complexion, and noting her role as a ‘Deck Boy’.

During this time April fell into a deep depression. As well as her existing feelings about her gender identity, her body was changing in ways she did not understand, growing breasts and not developing as those around her were, with their deepening voices and facial hair. April would later reflect that she may have been born intersex (although this was sometimes used by individuals as a way to give more legitimacy to unconventional gender expression in the public eye). Either way, the language and visibility of intersex people was non-existent in the 1950s. April felt very alone and isolated.

In August 1952, April attempted suicide. She was dishonourably discharged and returned to Liverpool. A further suicide attempt followed, and she was sent to the psychiatric unit at Ormskirk Hospital and then Walton Hospital. Rather than being offered support with her gender identity, April faced electric shock therapy and was given testosterone treatment – essentially a form of conversion therapy (see footnote 6).

As soon as she was able to, she fled to London – leaving her beloved Liverpool – hoping to find somewhere she might fit in.

Le Carrousel

April initially found work in Lyons tea house on Piccadilly. As a known haunt for London’s LGBTQ+ community at the time, this would have showed a glimpse of the possibilities London offered. One of her first stays was remarkably in a boarding house with John Prescott, later deputy prime minister of the United Kingdom; at the time they worked together in a restaurant. April resourcefully found any work she could.

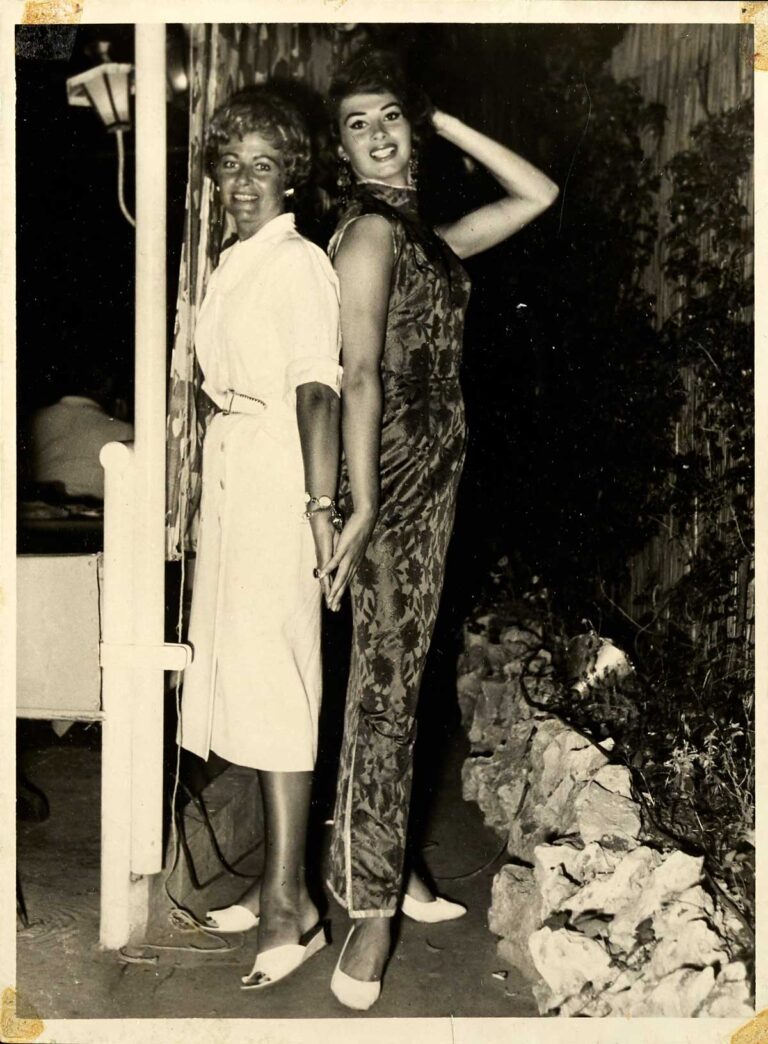

April had started dressing in feminine clothes and using the name Toni Ashley, intentionally choosing a more gender ambiguous name. Away from her family she could embrace the parts of herself she had felt forced to hide. She became aware of Le Carrousel drag cabaret, where some of the most prominent drag performers of the day took to the stage. April was given a job there, saying ‘Little did I know it at the time, but I had found another home.’ (See footnote 7.) The opportunities offered by London were eclipsed by those of Paris. April successfully performed night after night and toured with them to glamorous locations like Juan-les-Pins, on the Côte d’Azur, for Le Carrousel’s summer season.

In 1952, she became aware of the highly publicised medical transition of American actress Christine Jorgensen. Medical transition was seen as a relatively new phenomenon and such cases were often sensationally splashed across the front pages. Coccinelle, a fellow performer at Le Carrousel, had sought gender affirming surgery. April followed in her footsteps and went to Casablanca for her own procedure by the pioneering French gynaecologist Dr Georges Burou. The surgery was innovative and risky but April was driven by the ‘courage of desperation’. She was Burou’s ninth patient. Despite the significant trauma of this newly developing medical procedure, April described this as the best day of her life (see footnote 8).

April Ashley

In 1961, April renounced her birth name, changing her name by deed poll to April Ashley – inspired by the month of her birth.

At this time trans and intersex people, for example, could often change their sex on legal documents, and officials could be surprisingly helpful. There was no definitive policy and approaches differed across government departments. For example, in the 1950s the Ministry of National Insurance were keen to continue a ‘humanitarian approach’ despite potential public backlash, believing, ‘It is a matter of vital importance to them that they should be able to take up a job and live the life of the sex of their choice.’ (See footnote 9.) Birth certificates were more complex – evidence from doctors was required but changes were possible. The General Register Office were most willing to change birth certificates if they felt there had been a mistake at the time of the initial registration, rather than on the basis of a changed or newly expressed gender identity (see footnote 10).

After her change of name April got an updated passport and a women’s National Insurance card. She wrote, ‘I could do nothing about my birth certificate’ – this fundamental legal document still marked her as ‘male’ (see footnote 11). The process was not transparent, consistent or publicised. Did April, and people living through similar experiences, not have fair access to the knowledge that this document could be updated? April also did not have the medical connections or class privilege that could help navigate this potentially bureaucratic process (see footnote 12).

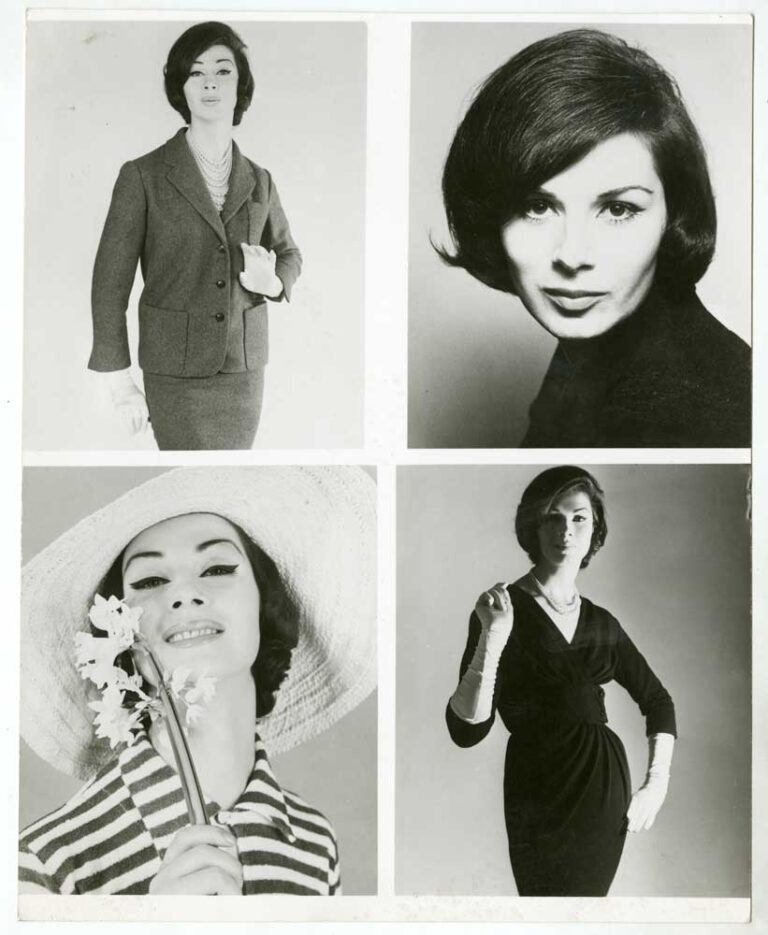

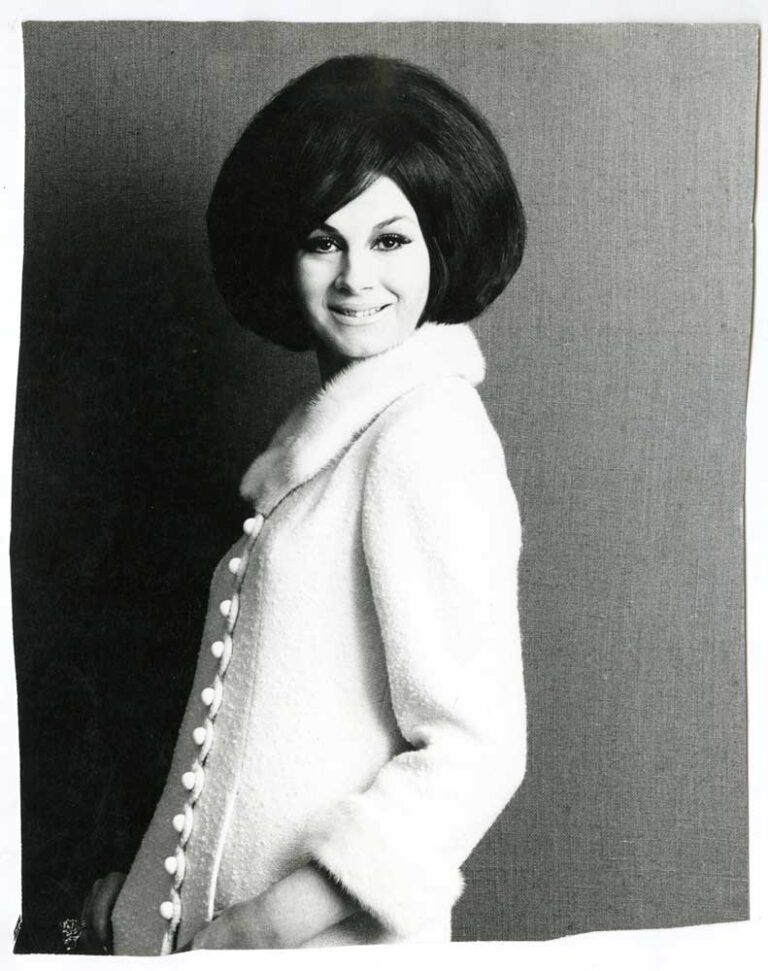

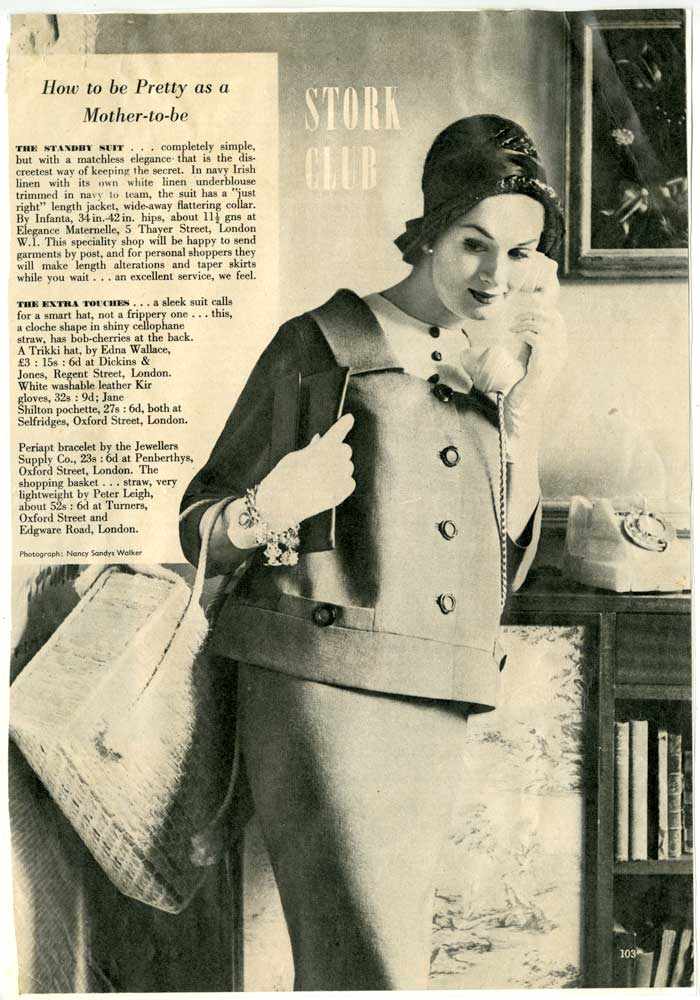

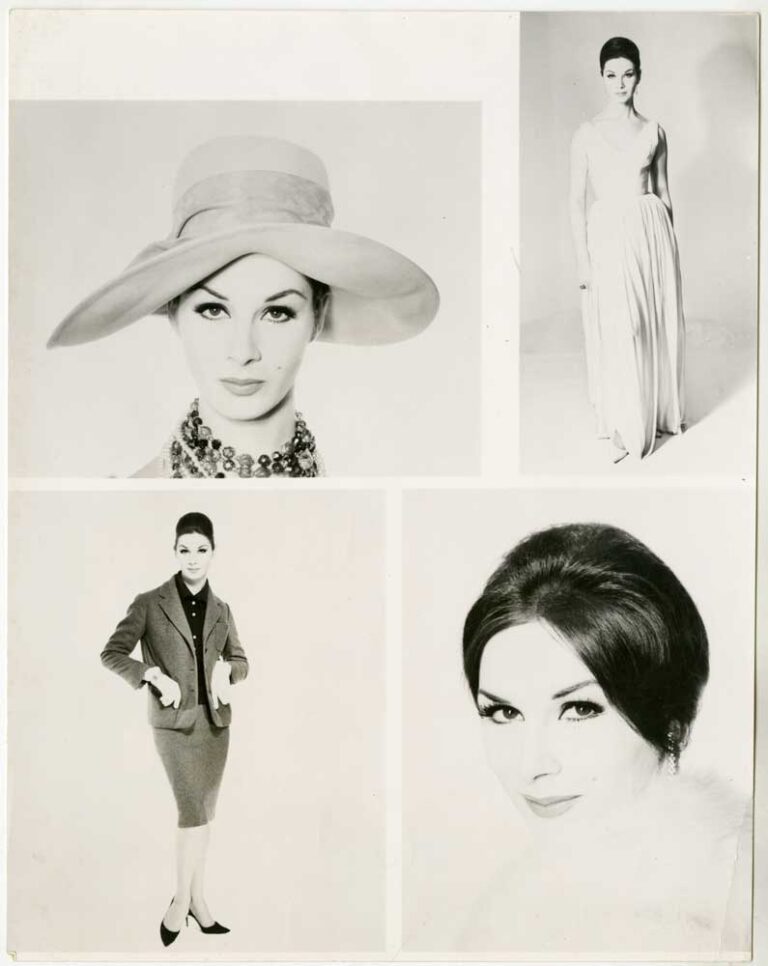

Spurred by her change of name, surgery and experience as a performer, April returned to London, which was in the throes of the Swinging Sixties. April quickly became in demand as a model, moving in society circles. Our records show April on various runway shows, in glamourous photoshoots and in magazine adverts during this period. She was even photographed by David Bailey for British Vogue. April also appeared on the big screen in the 1962 film The Road to Hong Kong. Although friends knew about her gender identity, the wider public did not. As she became more established and prominent, her fear of being ‘outed’ grew.

Public outing and marriage

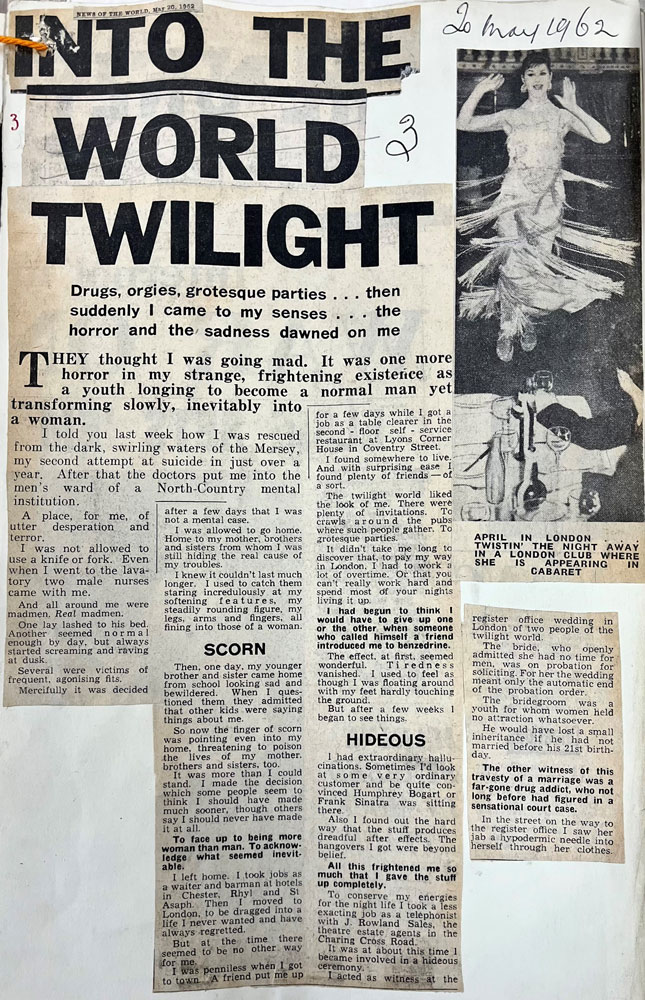

On 19 November 1961, The Sunday People ran an article under the headline ‘ “Her” Secret is Out’, revealing April’s assigned sex at birth and process of gender-affirming surgery. Someone April knew had tipped them off. Overnight everything changed. April’s name was dropped from her recent film credit and her modelling work vanished. April retaliated, serialising her own story through their competitor tabloid The News of the World, to reclaim this very personal narrative.

During this period, in late 1960, April had met aristocrat Arthur Corbett, who was married at the time and became obsessed with her. Arthur liked to dress in women’s clothes and envied April openly identifying as a woman, and her success at it. He supported her through the press turmoil. After Arthur’s marriage broke down, they started a relationship, but it was plagued by difficulties, including Arthur’s unpredictable temperament. April was unsure about marriage but finally agreed, wedding in 1963 in Gibraltar (see footnote 13). They did not seek legal guidance on the validity of their marriage (see footnote 14).

Just days later the relationship broke down. April wrote to Arthur, ‘I know I should never have married you…’ (See footnote 15.) Arthur returned to their villa in Marbella, Spain – which April said he had gifted her – and she stayed in London.

The pair remained separated. Over the following years April was financially troubled, suffering from a loss of earnings she had previously had from her modelling and acting work. April attempted to enforce her claim on the Spanish villa. When that was unsuccessful, her lawyer petitioned for maintenance under the Matrimonial Causes Act (1965). This was an ill-fated move. Arthur retaliated with a demand for annulment of their marriage. These actions were to have huge consequences for trans people globally.

We will continue April’s story in a second blog, coming soon.

Footnotes

- In writing these blogs the values of care and agency have been carefully considered, as has the ethical framework of Kit Heyam in Before We Were Trans, A New History of Gender (London, 2022)

- Ashley, April; Thompson, Douglas, The First Lady (London, 2006). p.3

- RG 101/4390. Although we do hold some records about April’s early life, this blog intentionally does not reference April’s birth name or show pre-transition photographs

- Ashley; Thompson, The First Lady. p.12

- Ibid. p.26

- Ibid. p.26

- Ibid. p.53

- Ibid. pp.111-130

- ‘Change of sex cases: issuing of new cards; amendment to records; change in contributions’, 1952-1976. PIN 43/590, The National Archives

- As outlined by the GRO in PIN 43/592, The National Archives

- Ibid. p.139

- Unlike individuals such as Ewan Forbes, Roberta Cowell and Michael Dillon. Playdon, Zoe, The Hidden Case of Ewan Forbes: The Transgender Trial that Threatened to Upend the British Establishment (London, 2021). p.54, p.70

- Ashley; Thompson, The First Lady. pp.275-280

- Judgment: Corbett v Corbett (otherwise Ashley)

- Ashley; Thompson, The First Lady. pp.200-201

Excellent! I worked on April’s archive at Liverpool Central Library as mentioned at the TNA Advisory Board meeting this month.

What a compelling story, so engaging. Looking forward to part 2!

What an amazing lady beautiful inside and out. I would love to have met her I had friends in Pitt Street I was brought up not far from there I lived in Caryl Gardens. I find it so sad hearing the way her mother treated her she was her child. I would love to know if she had any further contact with her family. So pleased she was buried next to her father. RIP beautiful lady from Karen Harris ❤️