On 5 December 1922, the Irish Free State Constituent Act ratified the Articles of Agreement signed by British Cabinet Ministers and members of the Sinn Fein delegation almost a year earlier on 6 December 1921. Two of its signatories on the Irish side – Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins – were now dead and its leading proponent on the British side, Prime Minister Lloyd George, had fallen from power in October 1922. The following day, on 6 December, it became law in the new dominion.

A new relationship

The draft of a bill for the Irish Constitution appeared before the new Andrew Bonar Law-led Conservative cabinet on 24 November 1922 – it is viewable in CAB 24/140/24. It is one of the ironies of history that a politician who resisted any change in the relationship between Britain and Ireland was responsible ultimately for ratification of a new Dominion constitution and relationship. Bonar Law, as Conservative leader, had in April 1912 stood to attention along with Ulster Unionist leader, Edward Carson, and some 70 other MPs when 100,000 Irish unionists marched in military formation at Balmoral, south Belfast, during the resolution against Home Rule. A lot had happened in the intervening 10 years, including a world war and an Irish War of Independence.

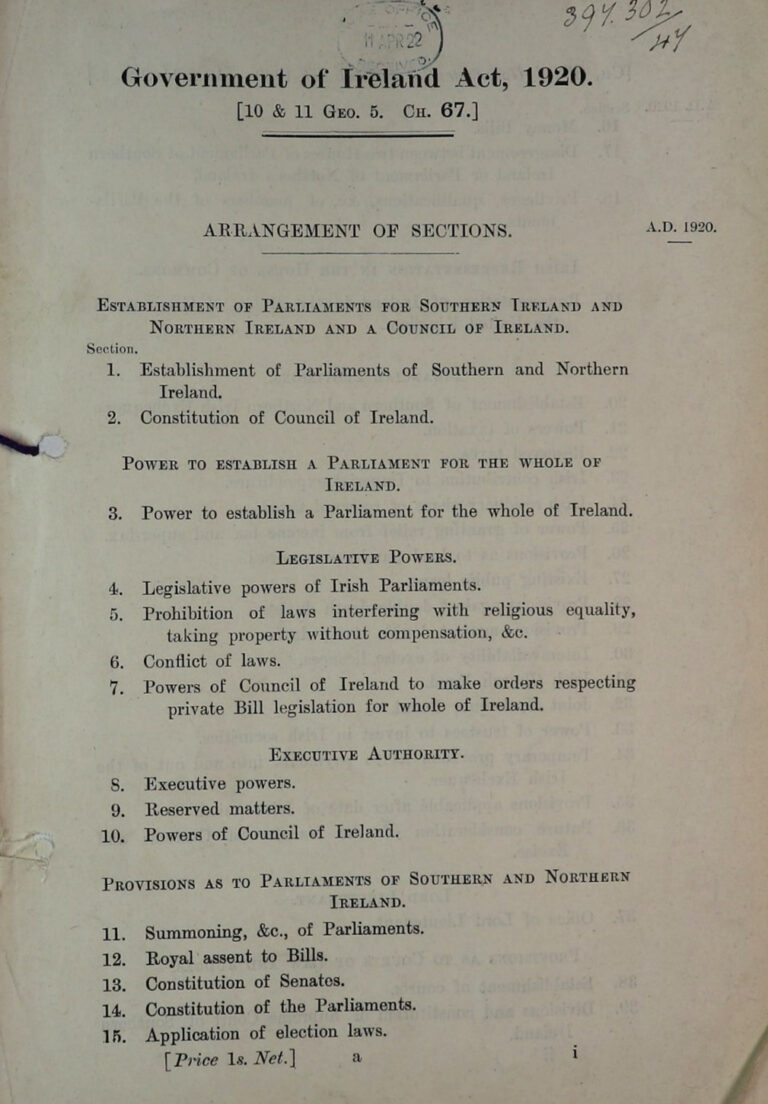

The Government of Ireland Act

Probably the most important piece of legislation in the period was the enactment of the Government of Ireland Act 1920, which effectively created two parliaments in Ireland and a form of ‘Home Rule’. The details of this act are found in HO 45/19974. Through this Act, Ulster was given its own parliament and guarantees that it would remain part of the United Kingdom, establishing a new constitutional and political arrangement-devolved government and partition. The Irish border demarcating the six counties of Northern Ireland from the rest of the country became a reality on 3 May 1921, as a consequence of the Act. It might be argued that only when the Ulster issue was settled did British politicians turn towards a settlement with the militant Irish nationalist Sinn Fein representatives, democratically serving the rest of Ireland.

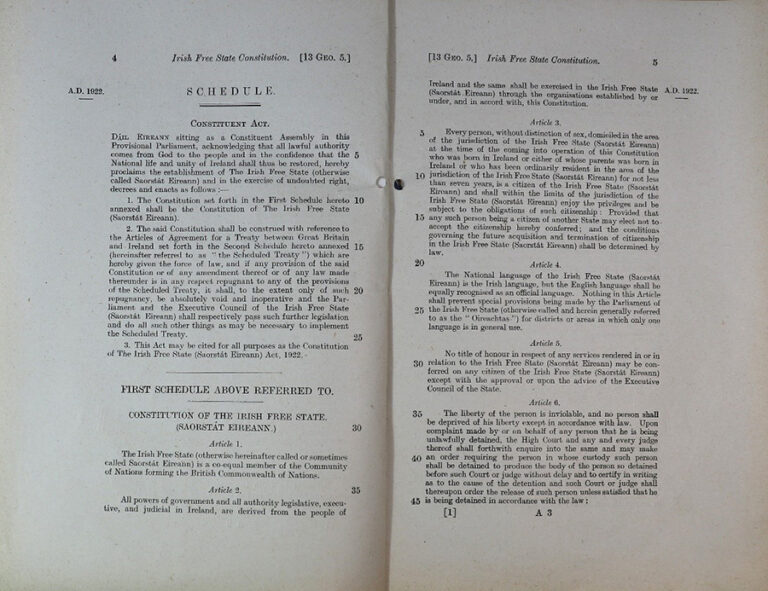

In the new Irish Free State (or Dominion State) of 1922, the new chairman of the Provisional Government, William T Cosgrave, urged the Dáil (Parliament) to approve the Irish Constitution when it met on 25 October 1922. The Act itself has five sections and a schedule. The schedule of the British Bill was the text of the Constitution of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Éireann) Act 1922, which had been passed in Ireland by the Third Dáil, sitting as a provisional parliament in October 1922. This Act itself had two schedules, the first being the actual text of the Constitution, and the second the text of the 1921 Treaty (the Articles of Agreement mentioned above). The UK Act’s preamble quotes section 2 of the Irish Act:

if any provision of the said Constitution or of any amendment thereof or of any law made there under is in any respect repugnant to any of the provisions of the Scheduled Treaty [the Anglo-Irish Treaty], it shall, to the extent only of such repugnancy be absolutely void and inoperative and the Parliament and the Executive Council of the Irish Free State shall respectively pass such further legislation and do such other things as may be necessary to implement the Scheduled Treaty.

The Act declared that the Constitution would come into effect upon a royal proclamation no later than 6 December 1922.

Earlier in the year Tory ‘diehards’ hoped that the fall of Lloyd George’s coalition would trigger the collapse of the treaty settlement. It did not. Before his fall from office, Lloyd George exchanged published telegrams with Cosgrave assuring him that the treaty would not be compromised. The passage of the Act was confirmed even before Bonar Law became the new Prime Minister when, at his first audience with King George V on 19 October, he relieved royal anxieties that the treaty settlement might be jeopardised by a change of government. (Source: Ronan Fanning, ‘Fatal Path’, 2013).

Conservatives accept the Act

To an extent the success of Bonar Law’s career rested upon the political partnership and friendship with Lloyd George; by October 1922 he had no appetite to re-open old wounds. His first major decision was to hold a special parliamentary session to pass the necessary legislation before 6 December 1922. On 16 November, the day after the Conservative victory at the General Election, he met with Lloyd George’s Cabinet secretary, Tom Jones, stating that ‘if the Treaty and Constitution must be put through it was better to do it handsomely than in any niggardly spirit’. Nor did Bonar Law resist the appointment of Tim Healy (an Irish Parliamentary Party MP) as the Free State’s first Governor General. Healy was seen by the British as a moderate within the Irish government. (Source: ‘Tom Jones Diary’, Vol III).

On 27 November, Bonar Law introduced the Irish Free State Bill in the Commons stressing that the treaty had already been approved by the previous parliament and no political party at the election had taken ‘any other view than that this treaty must be given a chance and everyone desires that this should be done’. (Source: Ronan Fanning, ‘Fatal Path’).

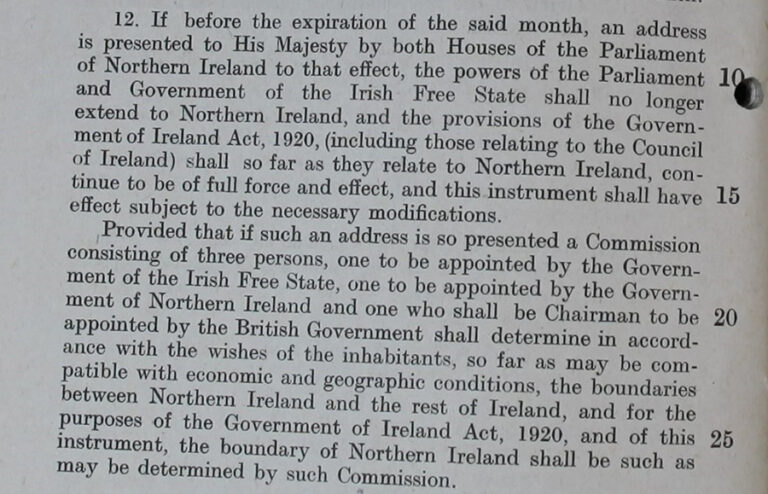

Opting out

Article 12 of the Anglo-Irish Treaty allowed the Parliament of Northern Ireland to opt out of its future inclusion in the new Irish Free State. On 7 December 1922, two days after the Act had passed in the British Parliament and a day after the establishment of the Irish Free State, the Parliament of Northern Ireland addressed the King, requesting its secession from the Irish Free State. The King replied shortly thereafter to say that he had caused his ministers and the Government of the Irish Free State to be informed that Northern Ireland was to do so.

The 26-county Free State was given independence in domestic affairs (including fiscal autonomy). Given the rapidly evolving nature of Dominion status inside the British Commonwealth, its ‘external’ freedoms would be wide-ranging and likely to expand. British use of three ‘Treaty Ports’ – in peacetime – and other facilities in war were guaranteed. Other arrangements were made for mutual defence of the Free State and the United Kingdom.

Crucially, however, from 6 December 1922 the Irish Free State had come into legal existence. The full text of the Act is available online.