Transparent papers are widely present in archives, libraries and museums, and yet their manufacturing process – both historical and current – seems to be a long-kept secret. As if it were Grandma’s treasured recipe, manufacturers don’t usually give away their production techniques, but as conservators, knowing how something was made determines how it should be taken care of.

I am currently an MA Conservation student at Camberwell College of Arts, doing a weekly work placement at The National Archives. As part of the ongoing research into transparent papers under Dr Helen Wilson, I am taking part in a project that aims to explore the link between manufacturing processes and ageing characteristics of transparent papers. As they age, the papers can become brittle and tear easily, with fragments in danger of getting lost during use. Moreover, transparent papers also discolour easily, leading to a decrease in their readability.

For this investigation we prepared some sample transparent papers that we could artificially age, in order to mimic real life conditions. Artificial ageing is usually carried out over weeks or months, compared to real life ageing done over tens of years. The paper’s ageing behaviour has been monitored using two scientific techniques: Spectrophotometry to monitor colour change, and Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy to compare the presence or absence of oils and waxes before and after ageing. These observations will help us to better understand the manufacturing methods of the historical papers in The National Archives’ collection.

Transparent papers have traditionally been made in three different ways: through impregnation with oils and waxes, over-beating of the pulp, or sulphurisation. Combinations of these were also used. Following historical recipes and considering resources, we decided to create samples with a variety of drying oils, mineral oils, and beeswax.

A mixture of linseed oil and turpentine is sponged on to both sides of the paper

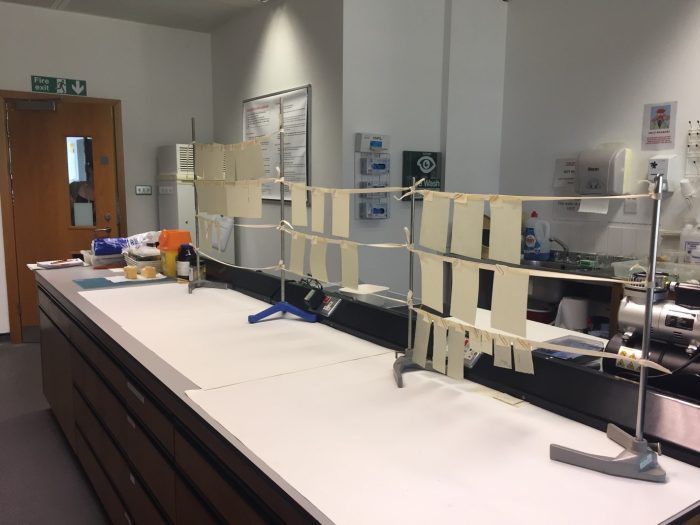

The samples were then hung to dry. The smell of the oils impregnated the Collection Care Department lab for a few weeks!

We also tried immersing the paper in hot wax. Excess wax was removed with blotting paper and a hot iron. This paper was more transparent

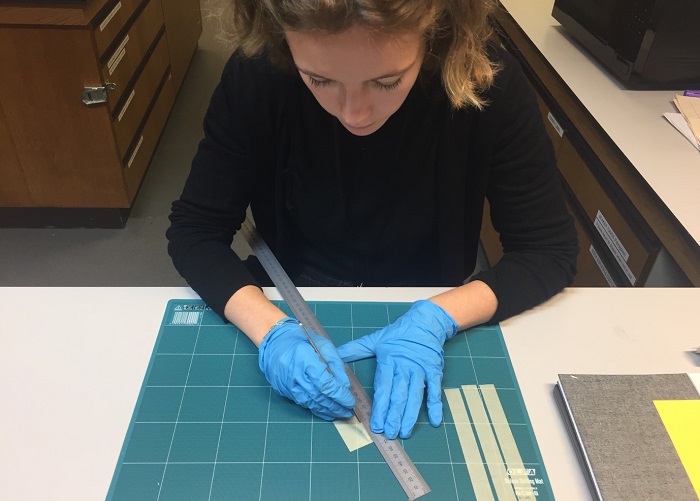

Once all the samples were prepared, they were cut to exact measurements, labelled and organised according to the duration of the ageing.

Through artificial ageing we can recreate years of deterioration in a matter of days by controlling the temperature and humidity in a thermal ageing oven. Following scientific standards for this ageing method, 14 days at 80°C and 65% relative humidity are being understood to equal approximately 157 years of natural ageing. Therefore, two weeks of artificial ageing has been the most representative for the majority of transparent papers within the archive’s collection.

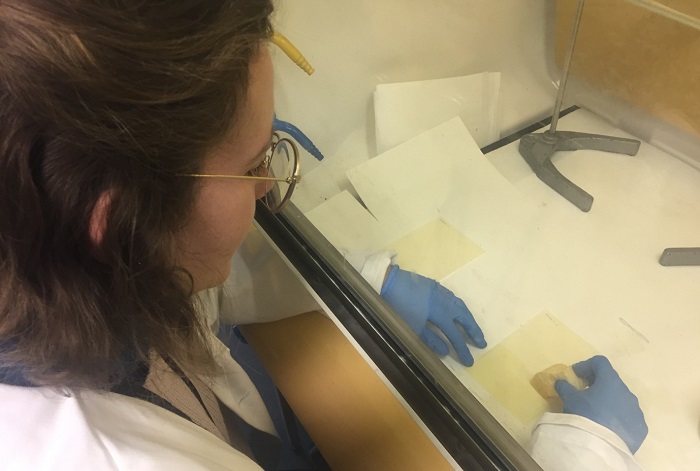

Careful preparation of the samples, using gloves, in order to prevent any contamination from my skin

Samples being put into the oven to age

After ageing, the samples were removed from the accelerated ageing oven and analysed using the two aforementioned scientific techniques. Once the data is fully processed, we will be able to draw conclusions. In the meantime, we have already observed that the colour changes after ageing are comparable to the range seen in collection material. Moreover, differences in manufacturing methods result in different responses under UV light and IR radiation. This may prove to be a useful tool for the identification of the transparent paper’s manufacturing methods and for their conservation.

Two-week aged model transparent papers (80°C, 65% RH). Equivalent to approximately 157 years of natural ageing

As a conservation student who comes from a scientific background and is very keen on heritage science, this project is a real treat! I am gaining invaluable skills as well as enjoying myself, and I hope to apply this research to my final year project at Camberwell. I also hope that the analytical and instrumental skills I am learning at The National Archives will contribute to my career as a paper conservator in the future, as I hope to find a balance between practical conservation work and conservation science.

Special thanks to Maria Borg and Alice Guida for helping with the making of the samples.

Dear Arantza Dobbels,

I am an Artist work at present on a collection of wood cuts using Japanese paper,

I read your article with interest as I am looking for a reliable, stable method of making some areas in my prints transparent.

Have you published your recipes? I would be very interested in trying them,

Many thanks,

Andrew James

A wonderful work

Really glad to see ur blog

Will u please tell how to make invisible water mark on hand made paper sheets

Thanks

Hi, I’m very interested in your research. I am a printmaker and I work on Japanese papers a lot specificallyGampi shi. I have been using linseed oil to make the paper even more transparent as I layer it so that the work behind can be seen more clearly from the front.

I was really alarmed to see the results of your aging process as I am worried that work I have sold will turn quite yellow over time I have used wax as well, but it tends to crease when you transport it.

Is there any chance you could let me know what was the least yellowing agent that you used on the papers? I see there that some of them are still quite white. I am working on a project at the moment and I’m very interested in keeping my papers as pure as possible. Any advice would be appreciated. I’ve just set up a print making atelier in Sydney and this is something that I’m working on at the moment very best and what a great project !

Jenny robinson

Insta @jennyrobinsonprints