In our latest video, Emilie Cloos, our loans and exhibitions conservator, treats us to a quick guide to microfading, explaining what microfading is, and why and how we use it in The National Archives’ Collection Care department.

The loans and exhibitions team in our Collection Care department spends a lot of time looking into light management. Light is necessary for everyone to see our amazing collection, but it is also one of the main agents of deterioration. Over time, light can alter the chemical makeup of our records, changing the physical properties of paper and changing the colours of inks, paints and dyes found in the records. As a result, we strive to find a balance between access and the preservation needs of our collection.

The National Archives has a lighting policy, which contains light sensitivity categories. When we want to display a record, it gets assigned a light sensitivity category and with that a light budget, which is how much light the record can receive per decade. Our collection items cannot last forever, but we aim to extend their ‘lifetime’ by managing a document’s light budget and reducing the instances of noticeable differences.

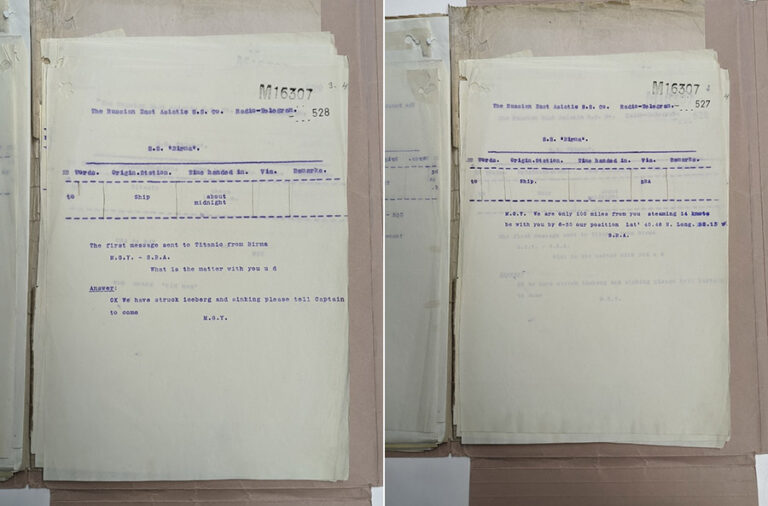

A just noticeable difference marks the point at which a change will be visible to the naked eye. For more traditional materials (such as paper and iron gall ink) the conservation and heritage science communities have built up a good level of understanding around the effect of light. However, we cannot always be certain what an object is made out of and how certain media, certain colourants for example, will react to light. That is where science can help us, in the form of a microfadometer.

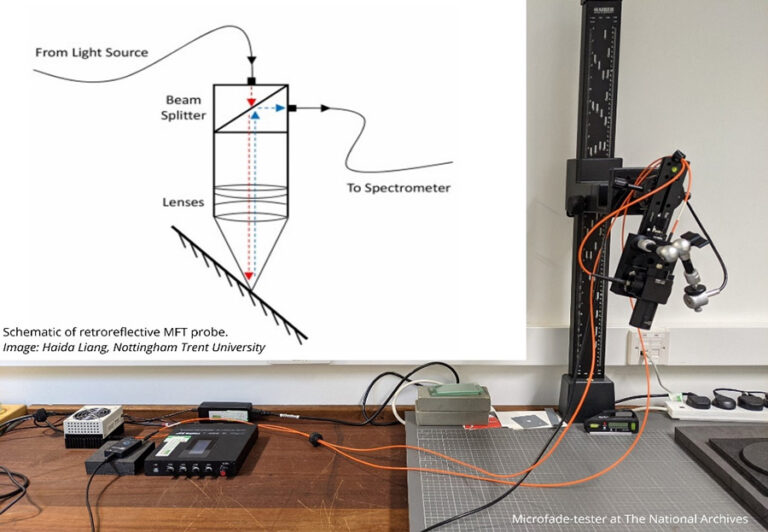

As a brief introduction a microfadometer – or microfade-tester – is a piece of scientific equipment that enables us to accelerate light fading, allowing us to predict the light-stability of an object and how it may change when exposed to light during an exhibition. A probe shines a very high intensity light onto a small spot to induce accelerated colour change, and the probe collects what is reflected back.

The light that is reflected back is recorded by a spectrophotometer. The spectrophotometer allows us to convert the light into colour co-ordinates which enables us to identify the colour change in the small spot we shone the light on to.

The test is micro-destructive, as it will change the colour of part of the document, but the spot is so small (0.3mm) that, except in very rare cases, it cannot be detected with the naked eye. In the Collection Care department we use this method to aid in our decision making, as it gives an indication rather than a definite answer.

In our latest video Emilie Cloos, our loans and exhibitions conservator, explains what microfading is and how we use it. You can watch the video here or on The National Archives YouTube channel: