200 years ago, on 5 May 1821, Napoleon Bonaparte, former Emperor of the French, died on the remote Atlantic island of St Helena.

The story of his fateful defeat at Waterloo and of his exile to St Helena by the British in 1815 is well known, so I will look today at what happened after his death.

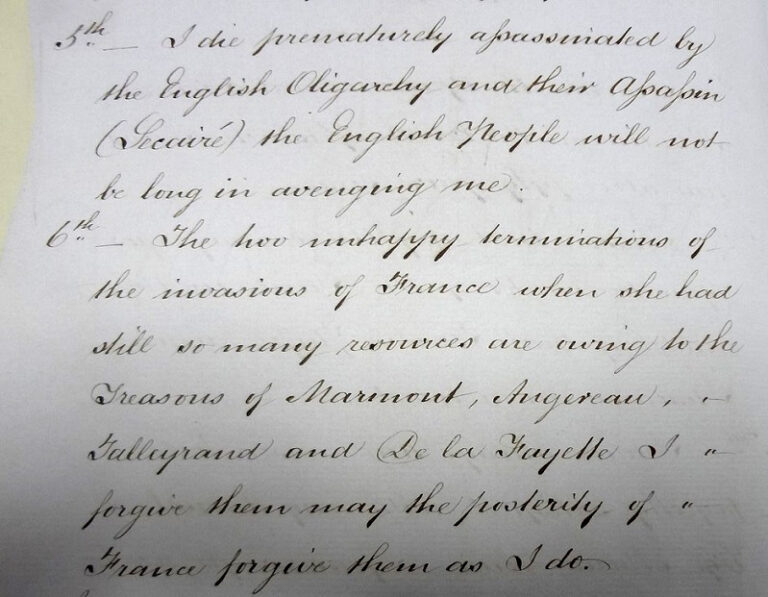

‘I die prematurely, assassinated by the English oligarchy and their assassin’

Napoleon knew how to bear a grudge and take it to the grave. His will, which he started handwriting mid-April 1821, was extremely political in nature. When the news of his death reached Europe in July, the French government, concerned it might cause unrest in the country, was rather anxious to get their hands on it.

No-one escaped Napoleon’s wrath. Britain and the Governor of St Helena obviously featured in good place – he had been convinced that his exile on a remote, windy island had caused the deterioration of his health: ‘I die prematurely, assassinated by the English oligarchy and their assassin’.

He named and shamed the ‘traitors’ he held responsible for his final defeats (Marmont, Augereau,Talleyrand and Lafayette), as well as his brother Louis. He also reminded the Bourbons, back on the throne of France, that their position wasn’t that secure and that they could be toppled anytime: ‘I recommend my son never to forget that he is by birth a French prince’.

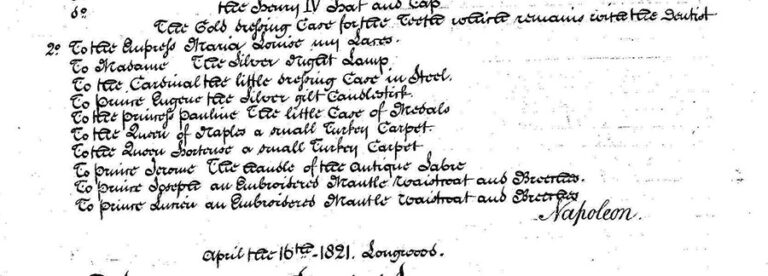

The will was proved in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury in August 1824. Napoleon left most of his possessions and money to those who had been most faithful to him, his son and veterans of his military campaigns. Other family members mostly inherited objects of sentimental value – Prince Eugene got a candlestick, for instance, Prince Jerome the handle of an antique sabre, Prince Lucien some clothes, his sisters small Turkish carpets…

It was only in December 1852, a few days after Napoleon’s nephew was crowned Emperor of the French, that it was ‘considered desirable, on grounds of public policy’ to return the original handwritten will to the French (TS 22/2). It was presented to Napoleon III in 1853, and is now held by the French national archives[ref]https://francearchives.fr.[/ref].

The ‘Return of the Ashes

(Note: Napoleon wasn’t cremated; the term ‘ashes’ refers here to his mortal remains. The return of remains is known in France as ‘le retour des cendres’).

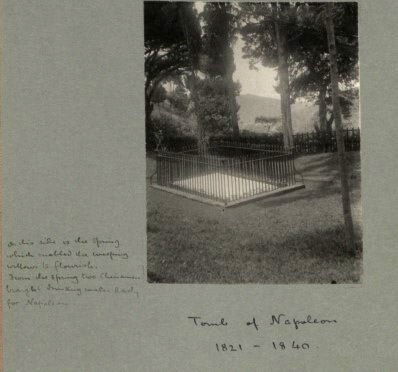

In his will, Napoleon had been quite clear about where he wanted to be buried: ‘I desire that my ashes may repose upon the banks of the Seine, in the midst of that French people whom I have so much loved.’ As we know, this didn’t happen and he was laid to rest in the Valley of the Geraniums in St Helena, under a bare stone slab surrounded by weeping willows.

In July 1821, a pamphlet started circulating in Paris. ‘Napoleon is no more,’ it stated, ‘we are claiming his ashes’. In September, Bertrand and Montholon, who had followed the emperor into exile, wrote to the King, asking for Napoleon’s body on behalf of his mother, Letizia Bonaparte, better-known in France as Madame Mère.

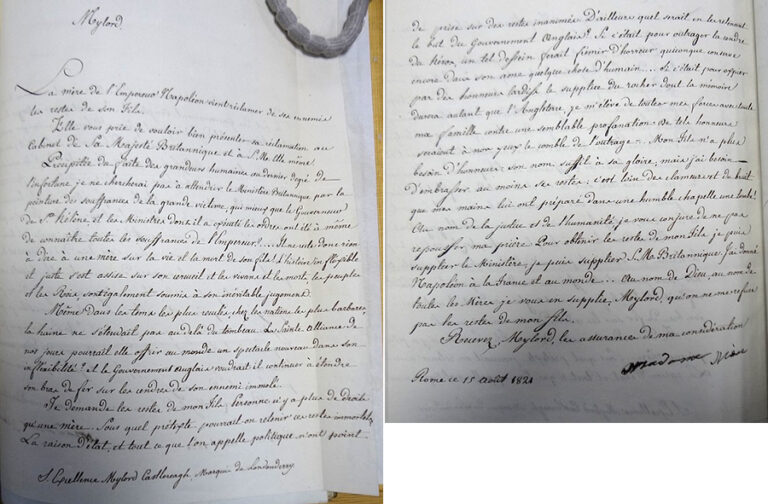

They also forwarded a letter to the Foreign Secretary, Lord Castlereagh, from Madame Mère herself, begging to be ‘allowed to water the tomb with her tears’.

‘To get my son’s remains, I am prepared to beg the Ministry, I am prepared to beg His Britannic Majesty. I gave Napoleon to France and to the world … In the name of God, in the name of all mothers, I beg you, Mylord, do not deny me my son’s mortal remains’ (FO 27/263).

The rather dramatic language she used, though, was unlikely to help her cause. ‘Even in the most ancient times, in the most barbaric nations, hatred didn’t go beyond the grave’, she wrote. The British ambassador to France, Charles Stuart, concluded ‘it would be more prudent to let the matter sleep for the present’.

In 1821, bringing Napoleon’s remains back to Europe hadn’t even been considered by Britain. Besides, the French government wasn’t too keen on the idea either. Louis XVIII, who had spent years in exile, and had had to flee again when Napoleon escaped from Elba, was not very well disposed towards the late Emperor. Napoleon was dead, but he was still dangerously popular – the return of his mortal remains could spark riots.

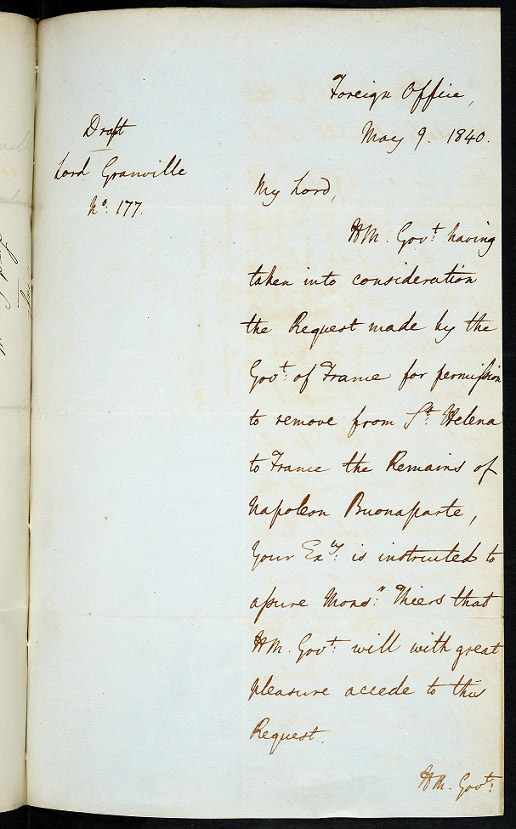

By 1840, however, the political situation had changed. Louis-Philippe needed to give his image a bit of a boost and therefore agreed to the return of Napoleon. At the beginning of May, the French Government officially requested the return of Napoleon’s remains.

The British government readily agreed. Returning the remains would be, they hoped,

‘proof of the desire of HM Government to extinguish every remnant of those national animosities which, during the life of the Emperor, arrayed the French and English people in arms against each other’ (FO 27/599).

The French would send a delegation to St Helena to retrieve the remains, led by Louis-Philippe’s son, the Prince de Joinville. After a slight delay caused by Joinville catching measles, they set for St Helena in July and reached the island on 8 October 1840.

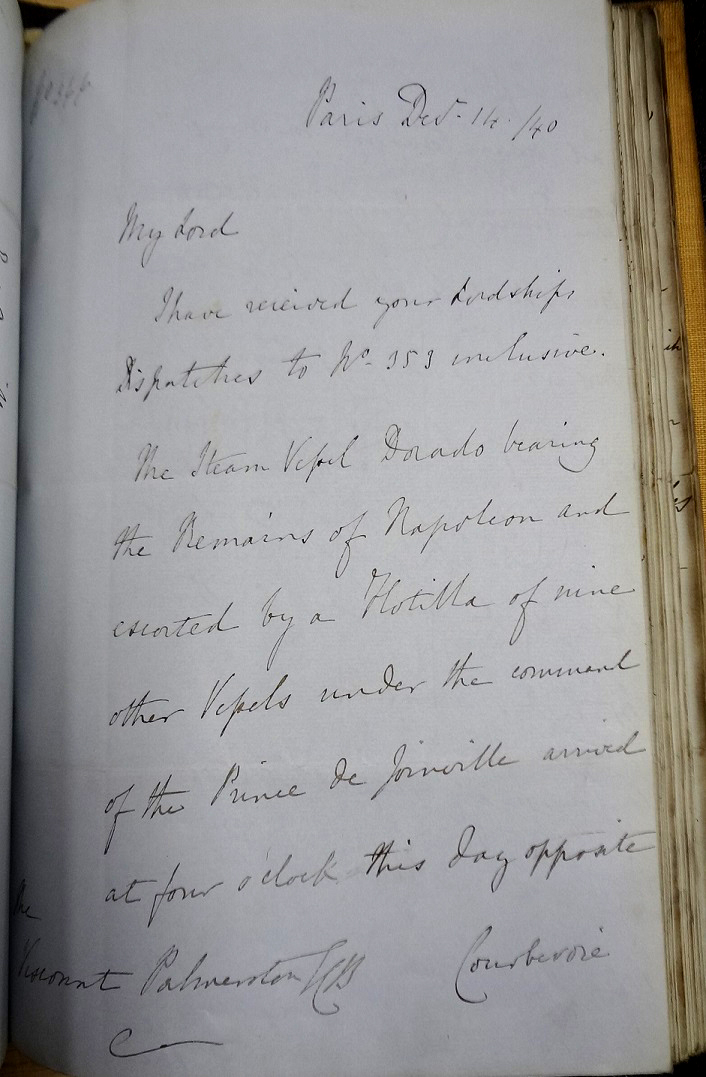

The exhumation started at midnight on 15 October. By 10 in the morning, the coffin was exposed and the (‘very well preserved’) body revealed. On 18 October, 25 years after he first set foot on the island, Napoleon finally left St Helena. He reached Courbevoie, northwest of Paris, on 14 December.

It was bitterly cold on 15 December 1840 when Napoleon left Courbevoie on his very last journey, in a very large, mostly military procession which carried the coffin, as Granville, the British ambassador, wrote to Palmerston, ‘from Neuilly up the avenue to the triumphal arch of the Etoile, and from there through the Champs Elysées to the Place de Louis 15, and then over the bridge of Louis 16, to the Hotel des Invalides’[ref]Using modern names, this means from the Quai du President-Paul-Doumer, up the Avenue de la Grande Armée to the Arc de Triomphe; down the Champs Elysées to the Place de la Concorde and across the Pont de la Concorde to the Invalides. [/ref].

Not exactly ‘upon the banks of the Seine’, but close enough!

The French domains of St Helena

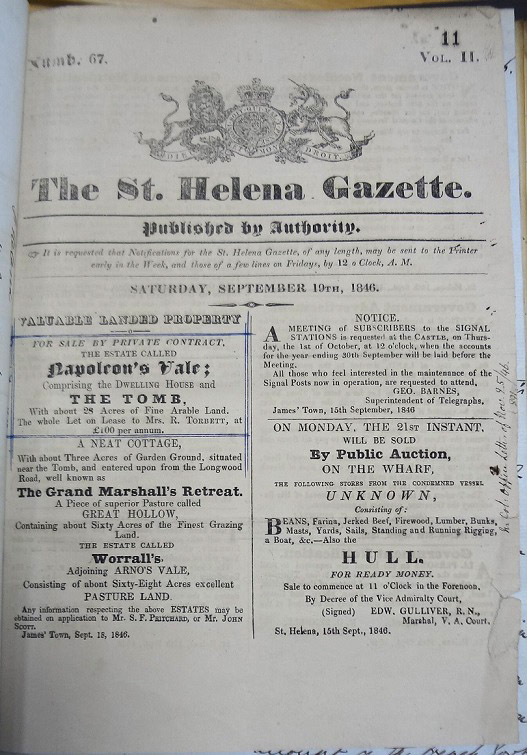

In 1846, Napoleon’s house on St Helena, known as Old Longwood, and his tomb came up for sale. French naval officers asked whether they could buy the estate, but as the remains had been returned to France, Palmerston couldn’t really see the point. Besides, foreigners weren’t technically allowed to own land in St Helena.

The question was raised again in December 1852. It was a rather complicated issue. The Longwood estate belonged to the Crown, but had been leased in 1851 for 21 years, and turned into a rather profitable farm. It was, actually, ‘one of the few farms of any extent in the island’ – its loss would represent a serious loss of revenue for the St Helena government.

According to the terms of the lease, the tenant was allowed to ‘take down any part of the buildings of Old Longwood not required’. He did. Old Longwood House was in such a sad state that the Colonial Office suggested it might be better to remove the building altogether (FO 97/205).

The tomb and the land around it had been rented by the government of St Helena, and reverted to its owner, Stephen Pritchard, when the remains were removed in 1840. It quickly became clear that Pritchard would ask for as high a price as he could get away with.

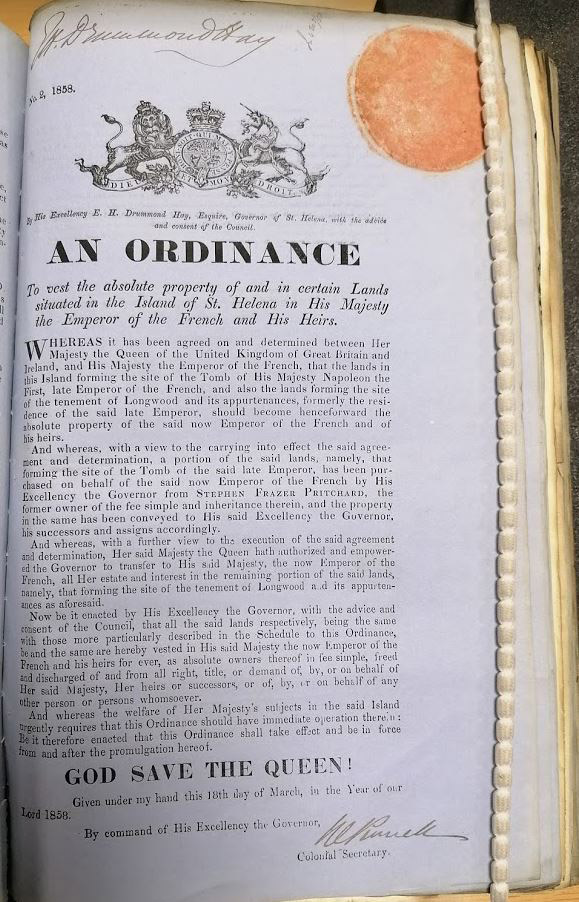

In July 1854, the legal advisers of the Colonial Office declared that foreigners could be allowed to buy land on St Helena. To avoid exorbitant prices, the (slightly convoluted) plan was for the government of St Helena to buy the properties and subsequently cede them to the French, who would then pay them back (FO 27/1046).

At the end 1856, as the French were becoming increasingly anxious to settle the matter, it was rumoured that Phineas Barnum, of circus fame, was interested in buying the tomb. This understandably increased French anxiety. In March 1857, the French ambassador, Persigny, wrote to the Foreign Secretary, saying the Emperor was prepared to accept whatever terms might be presented with. The price was much too high, but they couldn’t run the risk to lose the tomb and the estate to ‘speculators’.

Shortly thereafter, the Governor was authorized to proceed – but instructed he should still try to secure a better deal. On 21 July 1857, the transaction was completed. On 18 March 1858, the properties were ‘vested in His Majesty the now Emperor of the French and his heirs for ever, as absolute owners’ (CO 249/1).

Mid-May 1858, the French finally took the necessary steps to repay the money, a grand total of £7,100: £3,500 to compensate the tenant at Longwood for terminating his lease; £2,000 to compensate the government of St Helena for the loss of farming buildings; and £1,600 for the tomb itself (FO 27/1249).

Do note that, contrary to popular belief, the properties were not a gift from Queen Victoria to Napoleon III!

Today, as we mark the 200th anniversary of the Emperor’s death, nothing much has changed. Napoleon still lies under the golden dome of the Invalides; the properties on St Helena still belong to the French, and are administrated by the Ministry for Foreign Affairs; and Napoleon remains a divisive figure. In the words of St Helena Governor Edward Drummond-Hay, ‘viewing the question as a political one (…) I refrain from intruding any opinion’.