This blog article is part of the 20sPeople season – a season of exhibitions, activities and events from The National Archives that explores and shares stories that connect the people of the 2020s with the people of the 1920s.

‘I have read the account of the opening of the Enham Village Centre with much interest, and I was much struck by the promptitude with which you have got your first hundred men installed. It is only by institutions of this sort that we can repay some of the debt that we owe to those who fought for us, and I wish you every success for the future.’

Field-Marshal Haig, November 1919[ref]The National Archives. Catalogue ref: PIN 15/37.[/ref]

And what a future this scheme had! Beginning in 1919 as Enham Village Centre, to help men disabled as a result of the First World War, the charity is still in full force today as Enham Trust – who support disabled people to live, work and enjoy life to the full, as independently as possible[ref]’What We Do’, www.enhamtrust.org.uk/what-we-do.[/ref]. This blog will focus on the beginnings of this charity, and the work it did in the aftermath of the First World War.

The origins

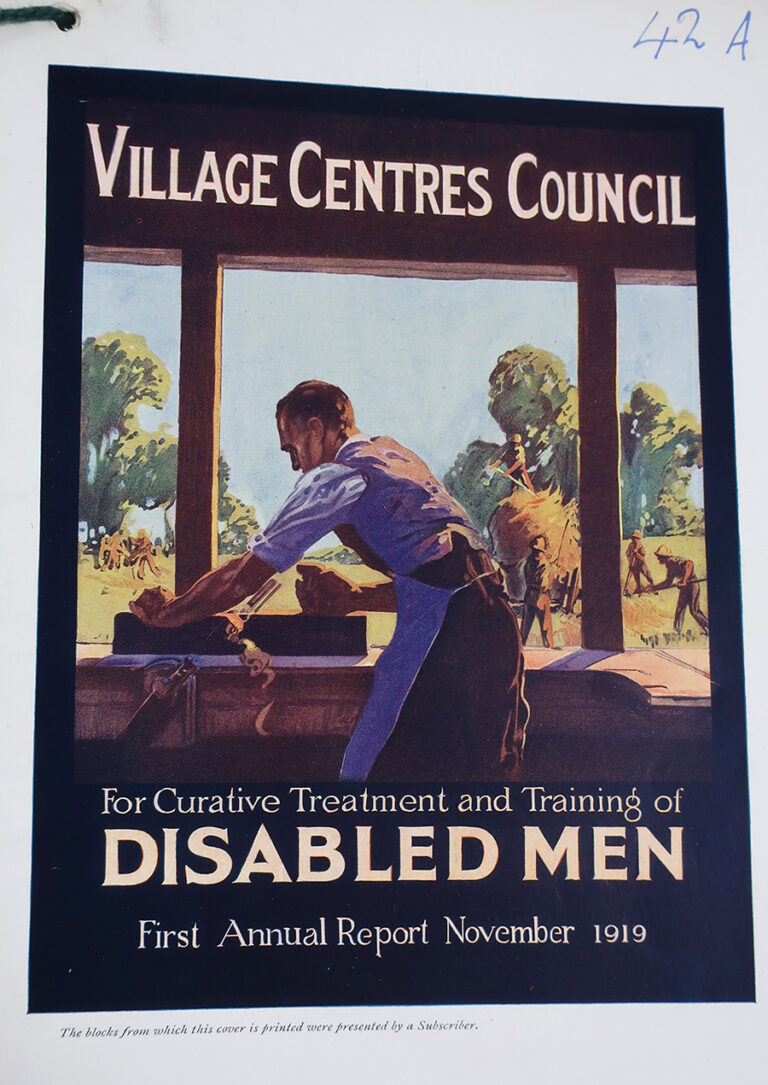

Over one million British men were disabled by disease or injury as a result of the First World War. Numerous schemes, charities and institutions were set up across the country to try to help these men upon their return to Britain – ‘Villages Centres Council for Curative Treatment and Training of Disabled Men’ (pictured above) was one such scheme. Like many others, one of the main aims of Enham was to enable these men to return to a trade, or learn a new one. Initially, six objectives were set out:[ref]The National Archives. Catalogue ref: PIN 15/37.[/ref]

- To assist the State in accelerating the restoration to health and fitness for work of ex-Servicemen who were injured in the Great War by disablement, which has caused their discharge from Navy or Army, but can be remedied by methods of medical treatment and mental and physical re-education.

- To associate with the medical treatment such vocational training in the open air and in workshops, especially for such occupations as can be practised on a large country estate.

- To offer attractive and co-operative conditions of social life which appeal to the men.

- To enable men with their families to occupy cottages and homes and ‘a bit of land’ on fair terms during the curative period, which may in many cases be prolonged.

- To speed the men’s recovery so that, with the help of their State Pensions and their own resources, and those put at their disposal by the Ministry of Labour, they may be able to return to their former homes and previous occupations, or earn a new livelihood in agriculture, horticulture and other healthy rural trades or callings.

- To utilise the Village Centres permanently in the interests of disabled ex-Servicemen, by way of settlement or otherwise, and as a national establishment for the restoration to health and for the physical re-education of other persons injured in the service of the State.

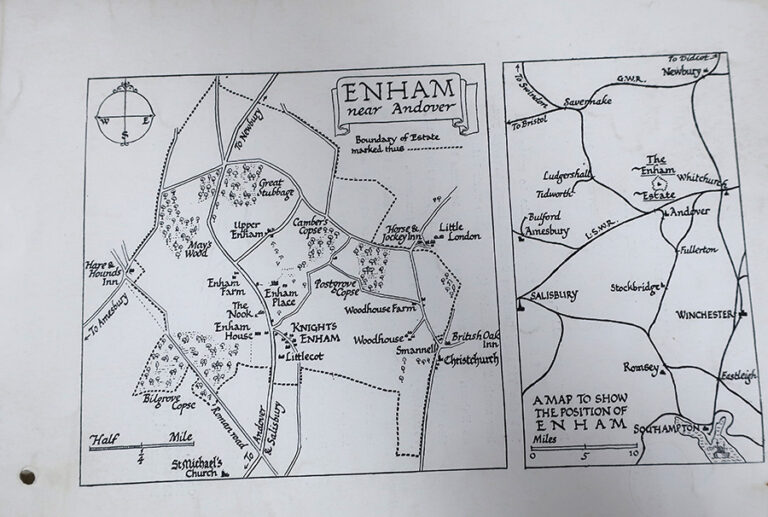

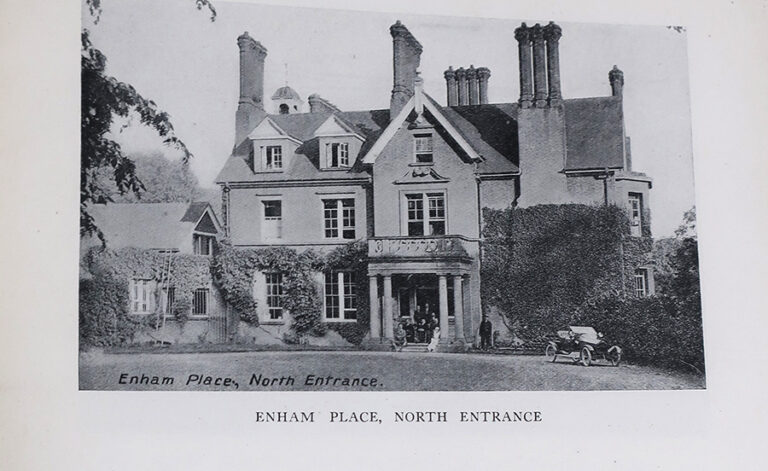

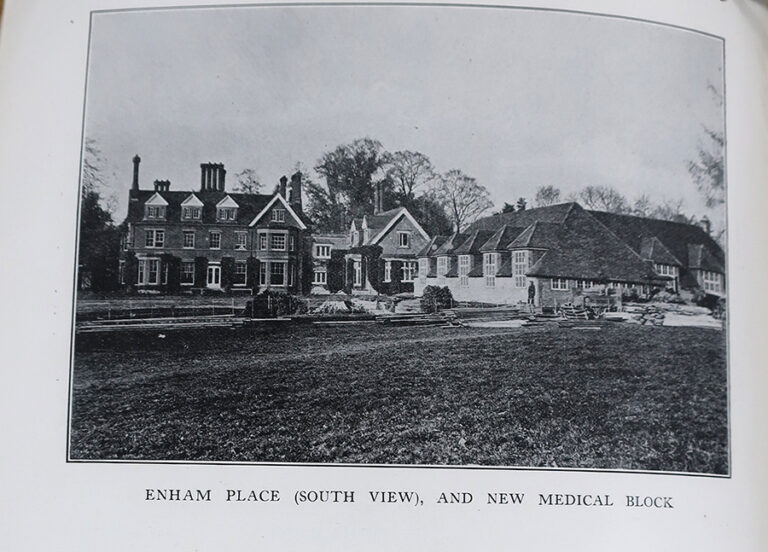

Enham Place, near Andover, was chosen for the site of the first Village Centre. Here there were 1,027 acres of good agricultural land, with four farms on the estate. There were also three large houses, two smaller houses, more than 30 cottages, and amenities such as a village hall, post office and a smithy.

Donations flooded in from the public, in the form of both money and miscellaneous objects for the establishment.

The work

The first resident was admitted to Enham in May 1919, and by the end of October 1919, 150 men were in residence in and around Enham Place. Two years later, this number had risen to 510. Men with all kinds of disabilities were represented, from those suffering from the effects of wounds (including injuries to the head and spine, and immobility of limbs) to those suffering the mental effects of their time at the Front.

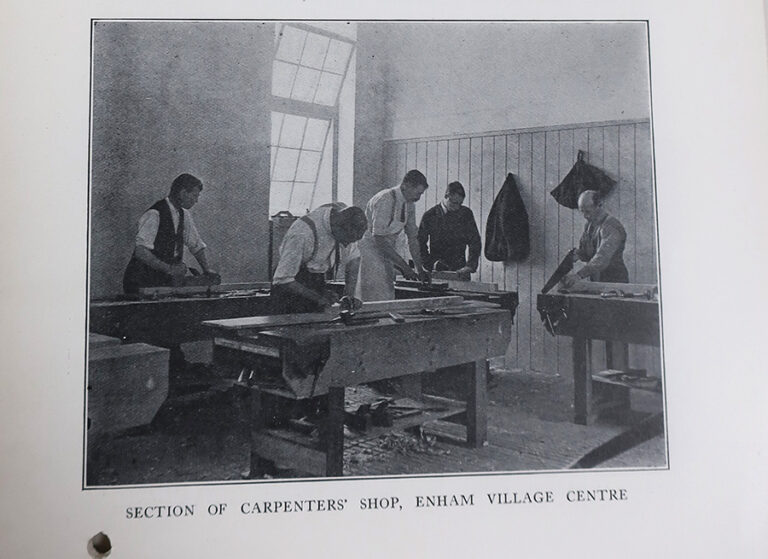

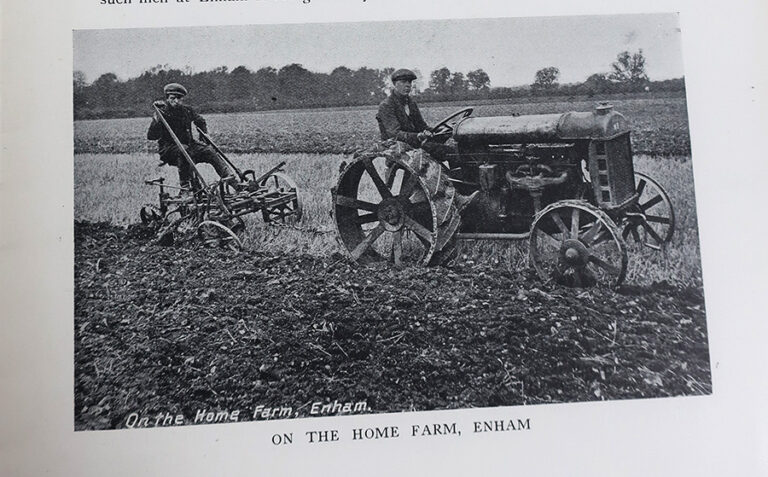

Considering the rural nature of the site, the industries that Enham specialised in were agriculture, horticulture and forestry. However, instruction was also given in the following: poultry-rearing, electrical fitting, basket-making, carpentry and joinery, boot and shoe repairing, and hand-made furniture. Many of these trades were the same sorts as were being offered in similar institutions elsewhere in Britain at the time. Those in charge believed that ‘only by combining treatment and training with personal supervision can the best results be obtained’.[ref]The National Archives. Catalogue ref: PIN 15/37.[/ref]

It wasn’t just training that Enham provided, but also various forms of treatment. A medical block was established on site, thanks to the British Red Cross Society, which provided facilities for exercising and training in the gymnasium, hyperthermal baths, and electricity and manipulations in the orthopaedic department, for example.

As they moved further into the 1920s, more buildings and accommodation were built for the men attending Enham. The need for more room and more beds was a constant issue that hospitals and institutions continued to battle with, as the extent of the effects of war on these men became more and more apparent. Not just temporary housing for those who would only spend a short time at Enham – there was also provision for those who would need permanent accommodation. Those running Enham understood that it was detrimental to many of the men to have to leave behind their wives and families to come to Enham, especially those with permanent disabilities, so they thought it best to provide family accommodation nearby. This, they hoped, would encourage men to stay there for as long as they needed, and not leave because they wanted to be with their families again.

Rehabilitation for disabled ex-Servicemen is an area where a fair amount of work has been undertaken. However, the origins of Enham Trust as an establishment for disabled veterans of the First World War might not have been as well-known, so hopefully this blog sheds some light on that early chapter.

20sPeople at The National Archives

20sPeople at The National Archives explores and shares stories that connect the people of the 2020s with the people of the 1920s. Accompanying the release of the 1921 Census of England and Wales, 20sPeople shows what we can learn by connecting with those who have gone before us. Find out more at nationalarchives.gov.uk/20speople.

My paternal Grandfather fought in WWI, he was born in Glasgow and fought in the trenches. He along with his wife and 3 young sons sailed out of Liverpool for Massachusetts in 1924. He refused to live in the UK when the Queen of England at that time would not allow Scottish soldiers to receive any wartime benefits. John Nisbet married to Elizabeth McLaughlin. My father was their youngest William Hugh Geddes Nisbet, born in September 1920.

This was an “old wives tale” which had no basis in fact at all. All British soldiers were treated the same.

Hi Joan

Please can you elaborate on your statement as i am currently studying wartime benefits in Scotland as part of my Masters degree. It sounds like an urban myth. I’m not aware the Queen would have any say in these matters as King George V was King in UK from 1910 to 1936 and has limited powers because Parliament decided who could receive benefits. My own research shows Scots received benefits including war pensions and disability pension, including my own family in Fife.

there were 400,000 Australian abd Bew Zealanders awaiting repatriation back to their homelands in 1914 General Sir John Monash the rdnuwned Australian General was incharge of their repatriation plans. Seeing ygat it was impossible to get thdm home in a short tine, he write to most UK Universities saying that tgese soldiers and aurmennhad left their own safe coubtrirs to help fight to szve Britain and Europe. He suggested that they should be offered free degree education in recognition of their majir contribution to the war effort In fact, sone 44,000 obtained degrees before embarking to home A wonderful repayment from a grateful Britain Thank you

Max Press OAM Sydney Grandson of Sgt Alred Lachlan Jack / 1432 AIF killed Gallipoli

28/08/1915 Hill 60