This blog article is part of the 20sPeople season – a season of exhibitions, activities and events from The National Archives that explores and shares stories that connect the people of the 2020s with the people of the 1920s.

On 18 October 1918, Sir Cecil Macready, the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, submitted a recommendation to the Home Secretary, Sir George Cave, ‘for the experimental formation of a body of Women Police’ (see footnote 1). Soon after, the Metropolitan Police Women Patrols were formed in 1919, led by Superintendent Sofia Stanley (footnote 2) This was the first time women were formally inducted into the Metropolitan Police.

The records of the Metropolitan Police and Home Office, held at The National Archives, provide us with a wealth of material on the Women Patrols. In this blog post, I will explore the early history of the Metropolitan Police Women Patrols, including their formation in 1919 and development during the 1920s.

Although women were involved in policing before 1919, it was decided that the work of women police should come directly from the orders of the police authorities. During the First World War, unofficial bodies of women undertook police duties. The National of Union of Women Workers employed Women Patrols on preventative work, and the Women’s Police Volunteers (subsequently renamed the Women’s Police Service in 1915) patrolled public spaces, offered advice and support to women and children, and assisted with the safety of Belgian refugees (footnote 3).

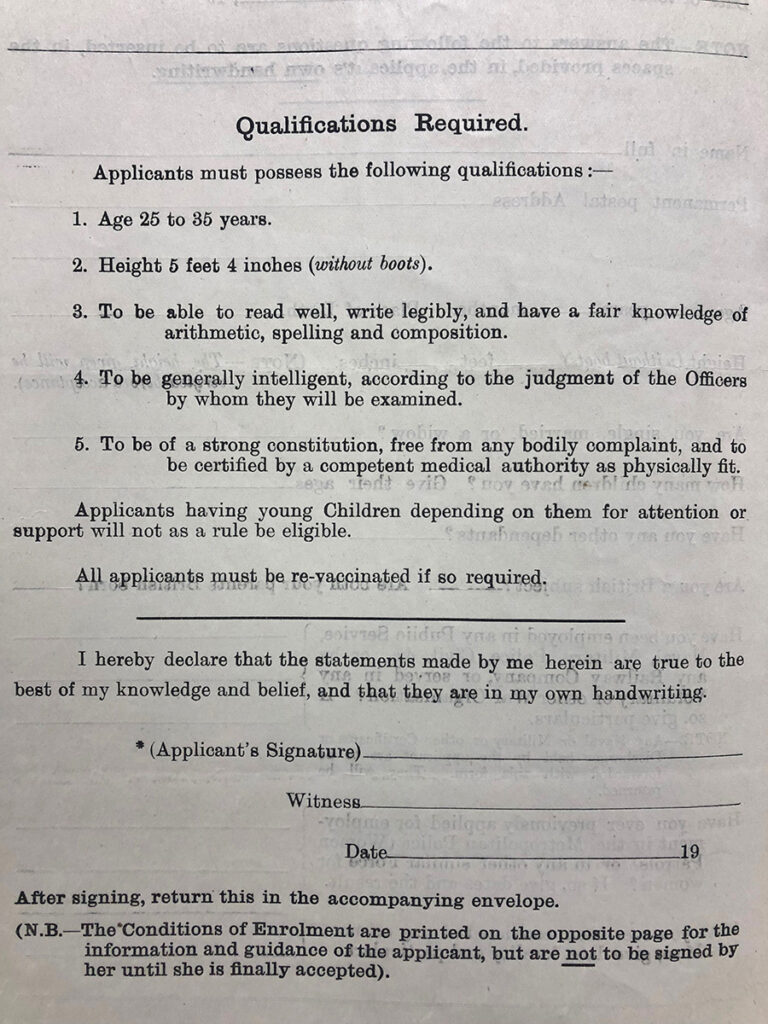

Those who were interested in joining the Women Patrols had to fill out an application form and ensure they met the qualifications as listed below (footnote 4).

Applicants had to be aged between 25 and 35, taller than 5 feet 4 inches, and women who had ‘young Children depending on them’ were not able to apply. The recruits then underwent five weeks of training; the Superintendent in charge of this training observed that ‘Police Women have proved good pupils, and as students, are in no way inferior to their male colleagues’ (footnote 5). Those who applied came from all social classes and often had experience in social work which was seen as a valuable asset (footnote 6). However, the Women Patrols were poorly paid and not entitled to a pension.

The role and responsibilities of the Women Patrols

The duties of the Women Patrols were very different to that of male police officers. As a precis by Macready, Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, stated:

‘The principal and primary duties of Women Patrols consist of dealing with women and children ill, injured destitute, homeless, and those who have been the victims of sexual offences, or are believed to be in danger of drifting towards an immoral life’.

Precis by Sir Cecil Macready, 26 February 1920, MEPO 2/2678, The National Archives

While many praised the valuable work undertaken by the Women Patrols on matters related to women and children, such work restricted women to traditional female concerns. The reference to an immoral life likely refers to women undertaking sex work, demonstrating how the Women Patrols were tasked with ensuring ‘moral standards’ were maintained.

The Women Patrols carried out seven hours of duty (an hour less than men). While they worked night shifts, they did not work on the streets after midnight (footnote 7). Instead, women took charge of female prisoners and of overseeing those who had attempted suicide (footnote 8).

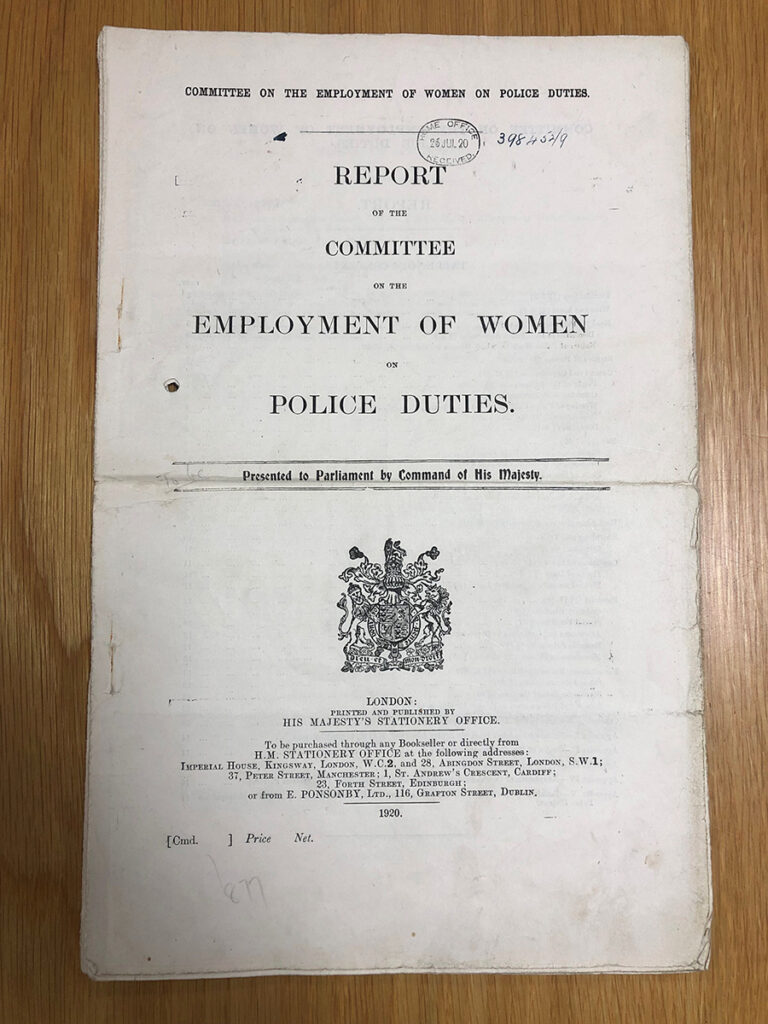

There was much debate as to whether women should be sworn in as constables. In 1920, the Committee of the Employment of Women on Police Duties was formed which produced the Baird Report.

The report stated that:

‘It is said that the work of the present policewomen is unduly restricted and could be extended if they had greater powers. The lack of such powers is declared to be a handicap and it is maintained that the possession by a policewoman would give her a greater sense of security, a higher standing to deal with prostitutes and disorderly girls more effectively and to enter without questions such places as public-houses or brothels.’

Report produced by the Committee of the Employment of Women on Police Duties, 1920, HO 45/11020/398452, The National Archives

The Baird Report concluded that women should be sworn in as constables in the same way as men, although their duties should be clearly defined. However, as this quote from the Baird Report shows, aspects of the Women Patrols’ work was often problematic, particularly their role in policing those who undertook sex work.

The Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, Sir William Horwood (who succeeded Sir Cecil Macready), wrote to the Home Secretary, Sir William Bridgeman, on 20 December 1922 that women were not able to perform all the duties of a police officer:

‘If they were sworn in they would have to carry out certain duties which, as must be obvious to everyone, they are not physically fitted to perform, and I should hesitate to accept the responsibility of any of these women being called upon by the general public’.

Letter from the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, Sir William Horwood, to the Home Secretary, Sir William Bridgeman, 20 December 1922, HO 45/11619, The National Archives

This was an opinion shared by many and, as a result, the Women Patrols were initially not sworn in as constables. This meant that they did not have the same powers as male police officers, such as the power of arrest. The Manchester Guardian reported that ‘it has often been urged that power of arrest is essential, but the other view has prevailed, that the woman should concentrate on preventative work and try to influence the girls.’ (footnote 9)

After much campaigning, especially from women’s organisations, and Nancy Astor and Margaret Wintringham, at this point the only two women MPs, the Women Patrols were granted the power to arrest in 1923 and were given the name ‘Woman Constables’.

Risk of disbandment?

After only three years in operation, the Women Patrols risked being disbanded altogether. In early 1922, the Home Secretary, Edward Shortt, was urged by the Geddes Committee (a Committee on National Expenditure) to disband the Women Patrols as a way of economising. The Geddes Committee recommended the ‘Removal of all women holding positions as Police Officers’ (footnote 10). This caused uproar from the women’s societies and press. On 20 March 1922, the Home Secretary received a deputation organised by the National Council of Women, which urged against their disbandment.

Sixty-five societies were represented at the deputation and both Astor and Wintringham were among the delegates. Astor opened the proceedings by stating ‘it is one thing to economise and another thing to abolish the Women Police’ (footnote 11). This was followed by a number of speeches which emphasised the valuable work of women police, including Eleanor Rathbone, the leader of National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship, and Mrs Wilson Potter, convener of the Women Police and Patrol Committee of the National Council of Women. Nonetheless, the Home Secretary concluded that while he recognised the value of women’s police work, ‘it could not really be described as police work proper … [and] was more in the nature of welfare work’ (footnote 12).

Although it was eventually decided that the Women Patrols would not be disbanded, their numbers were reduced to just 20 (footnote 13). The Committee on the Employment of Police Women produced a report in 1924 (known as the Bridgeman Report) which recommended that ‘at least as many women as were employed before the reduction in 1922 should again be appointed’ (footnote 14). Although numbers increased, progress on this remained relatively slow during the 1920s.

Prejudice and criticism

Women police were often met with resistance from male police offers and members of the public, who did not believe their presence was necessary. Frederick Mead, the Metropolitan Police Magistrate, argued that:

‘the law is in every respect satisfactory administered by the present male police; that women are unsuitable for duties which require the exercise of physical force; and that the work they can do…is either work which is extra to police duty proper (such as assisting the infirm or incapable across the streets) or is work that could better be carried out by philanthropic ladies not dressed in police uniform.’

Report produced by the Committee of the Employment of Women on Police Duties, 26 July 1920, HO 45/11020/398452, The National Archives

Others were more positive about their role. The superintendent at the Cannon Row police division praised the welfare and preventative work that women police undertook at Hyde Park. However, he went on to state that he would not welcome any additional women police as ‘I could not find useful work for them to do outside of Hyde Park, where the number already employed is amply sufficient.’ (footnote 15)

Although married women had been eligible to join the Women Patrols since its establishment in 1919, this changed in 1927. A marriage bar was introduced and applied to new female officers who joined the Metropolitan Police from 1927 (footnote 16). Although it initially did not apply to existing married women already employed, this came into effect in 1931 (footnote 17). The marriage bar on female officers was permanently abolished in 1946 in England and Wales.

The establishment of the Women Patrols in 1919 is an important landmark in history, as it was the first time women could formally join the Metropolitan Police. This marked a significant step in advancing women’s policing careers. However, women police experienced numerous challenges and aspects of their work were often problematic, particularly when looking at it from our modern day perspectives. In my next blog post, I will focus on the individual women who were employed in the Metropolitan Police, their personal experiences in the police, and provide more detail on the work they undertook.

Footnotes

- Letter from the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police to the Home Secretary, 18th October 1918, MEPO 2/2671, The National Archives.

- Precis by Sir Nevil Macready, 26 February 1920, MEPO 2/2678, The National Archives.

- Louise A. Jackson, ‘Women Police: Gender, Welfare and Surveillance in the Twentieth Century’ (Manchester, 2006), p. 18.

- Metropolitan Police (Women Patrols) Application for Enrolment, 17 February 1922, HO 45/11067/370521, The National Archives.

- Report on Women Patrols, MEPO 2/2678, The National Archives.

- ‘The Policewoman: A London Experiment’, Manchester Guardian, 19 March 1919, HO 45/11067/370521, The National Archives.

- ‘Women Police: An Unqualified Success’, Daily Telegraph, 29 July 1920, HO 45/11020/398452, The National Archives.

- ‘Women Police: An Unqualified Success’, Daily Telegraph, 29 July 1920, HO 45/11020/398452, The National Archives.

- ‘The Policewoman: A London Experiment’, Manchester Guardian, 19 March 1919, HO 45/11067/370521, The National Archives.

- Geddes Report, HO 45/11067/370521, The National Archives.

- Geddes Report, HO 45/11067/370521, The National Archives.

- Geddes Report, HO 45/11067/370521, The National Archives.

- Announcement from the Home Secretary, HO 45/11619, The National Archives.

- Report produced by the Committee on the Employment of Policewomen, 1924, p. 14, MEPO 2/2678, The National Archives.

- Confidential memo on Women Police, Cannon Row Station, 9 December 1927, MEPO 2/2678, The National Archives.

- Police Orders, 22 February 1927, p. 162, MEPO 7/89, The National Archives.

- Police Orders, 1 December 1931, p. 1297, MEPO7/93, The National Archives.

20sPeople at The National Archives

20sPeople at The National Archives explores and shares stories that connect the people of the 2020s with the people of the 1920s. Accompanying the release of the 1921 Census of England and Wales, 20sPeople shows what we can learn by connecting with those who have gone before us. Find out more at nationalarchives.gov.uk/20speople.